BEEF finds Oscar-nominated actor Steven Yeun painting a complicated, empathetic portrait of a man at the end of his rope.

Likable probably isn’t the first word that comes to mind when describing Danny Cho, the Southern California contractor played by Steven Yeun in the limited series from Lee Sung Jin, BEEF. Beset by financial woes and struggling under the weight of family pressures, Danny is ill-equipped to cope with the day-to-day stresses of trying to make ends meet, let alone come to terms with the trauma he has buried deep. It’s frankly unsurprising that one day, after his pick-up nearly collides with a Mercedes S.U.V. in a parking lot, Danny snaps and begins chasing the other driver.

What happens in the wake of that road rage incident unfolds over the course of BEEF’s wildly unpredictable 10 episodes, with Danny locked in an escalating campaign of retaliation and retribution with the woman driving that S.U.V., harried entrepreneur Amy Lau (an impeccable Ali Wong). Some of Danny’s behavior is despicable, but even when he’s at his worst, it’s impossible to completely vilify him — a fact that owes everything to Yeun’s tremendously empathetic performance.

“I appreciate that people feel like they can connect to Danny and root for him,” says Yeun. “I think the challenge as an actor is always: Are you going to leave this character in judgment or are you going to love him, too? It’s not an easy journey at times because you’ve got to face parts of yourself that maybe feel unlovable, but hopefully, in the end, we can connect that way.”

Connection is vitally important to Yeun. It’s a subject he returns to again and again, discussing what motivates him as an artist and what’s guided his decisions about the roles he accepts, dating all the way back to his breakthrough turn as the much-loved Glenn Rhee on the hit zombie series The Walking Dead. Following six years on the apocalyptic drama, Yeun took on parts in animated projects, including TV series Tuca & Bertie in which he appeared opposite Wong. He also began to build a feature film career with turns in such titles as 2017’s Okja and 2018’s Sorry to Bother You and Burning, the latter of which was selected as South Korea’s official entry for the Academy Awards.

Three years later, Yeun delivered the performance of his career thus far as a Korean father of two in Lee Isaac Chung’s 1980s-set family drama Minari. Earning a best actor Oscar nomination, Yeun made history as the first Asian American to be recognized in the category. Parlaying that success into highly personal, challenging roles — like traumatized former child star Ricky “Jupe” Park in 2022’s Nope and now Danny in BEEF — Yeun also is making the leap to comic-book blockbusters with Marvel’s upcoming Thunderbolts, in which he’ll star alongside the likes of Florence Pugh, David Harbour, and Harrison Ford. “I’m looking forward to it, but I know it’ll have its own journey,” Yeun says.

The actor talked with Queue about the experience of making BEEF, sparring onscreen with Wong, and how lucky he feels to have arrived at this place in his life.

An edited transcript of the conversation follows.

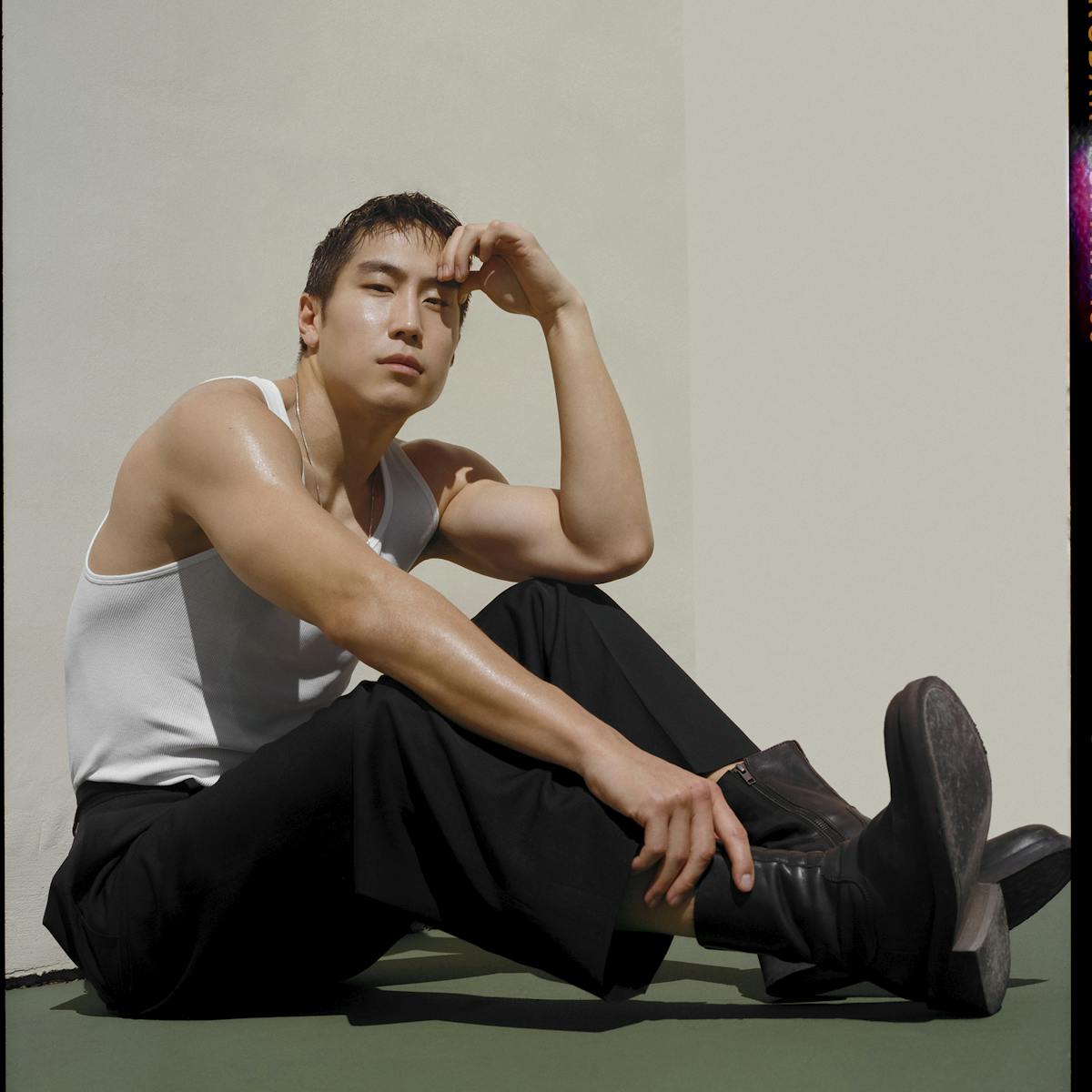

Steven Yeun

Krista Smith: BEEF delivers on every level. What about this show and this character spoke to you? I know that you have a little bit of a relationship with its creator, Lee Sung Jin, who you call Sonny. How did he talk you into it?

Steven Yeun: Sonny called me one day. I was actually in New York on a different project, and we were just talking. I’d met him a couple years back, and we just really hit it off. He called me up and was like, “Hey, I’m just running through some ideas.” Then he was like, “I’m also working on this idea for a road rage thing where two people get into a road rage incident and they just spiral and destroy each other’s lives.” I was like, “Give me that one.” It just immediately piqued my interest. He and I really often meet at — I’m trying not to sound so aggressively pretentious — this existential, angsty, spiritual deconstructive place where we’re just like, “What is this? Why is this? What does it all mean?” We talk from that place often for fun, if you can call that fun. We really got into it with BEEF. We talked a lot about the way in which the world, especially at that time and still today, seemed so polarized. We just wanted to explore that. It could be class, it could be race, it could be gender. There were so many things that we could talk about with this show. What was really exciting about BEEF was that it was less concerned about [pointing a finger] at [a specific] point of view, and more about excavating the humanity within that space.

When you were developing this, what kind of input did you have in terms of your own character development or the bigger arcs in this series?

SY: I didn’t have too much input or sway in the larger narrative or the character arc. I think that was for good reason because there’s that point, at least for me as an actor, in my process where I start to heavily identify with the character that I’m playing. It’s not a method thing, it just feels more like I’m sitting in an empathetic place for this person and I don’t want him to be rendered in a way that seems unfair. I’m being protective of the character. That’s where Sonny comes in. He can always be true to the story and true to the person. We would always have discussions, and I’d be like, “I don’t know if Danny should do that.” He’s like, “Danny’s doing that.” I’m like, “Okay.”

Steven Yeun and Ali Wong

That scene in Episode 3, when Danny walks into the church, and we already know that he’s a little bit lapsed — just being around that community and with what Danny’s going through, he just starts sobbing. That scene was so powerful to me. My mother was an eight-day-a-week Catholic. Religion was such a giant part of our life and my siblings and I, none of us go to church anymore. But when you do find yourself in a situation where you’re back in church, it does feel oddly familiar and cocoon-like. It brings up a past.

SY: Sonny and I would talk about this. The two of us don’t necessarily go to church anymore. But, for me, as an immigrant kid growing up in the Midwest, that was my only real safe space. I lived in the suburbs, we were fine, but I felt like I could put down a performance at church. Because it was a Korean church, there was another reality happening there, too, where maybe the ways in which we couldn’t assert ourselves in wider America, we could at least feel for ourselves in that particular place. I remember going back to church in my late 20s after I had stepped away from it for my whole college life. I went back and I just found myself nearing tears every single time. You’re like, What are you crying about? It took 39 years to maybe understand what was happening. But that moment for Danny, how I approached it was, he’s just carrying so much when he is outside. In that place, he can just dissolve into the back and just be there, and he’s accepted. To eliminate that internal voice that is so negative is such a beautiful and liberating and surprising feeling.

I was surprised that you could sing so beautifully. I did not realize that was in your arsenal of skills.

SY: That was fun, too. I used to lead praise at church. That was a very interesting scene to do. It wasn’t a calculated thing. It was just like, What will it be if I just try to go back to what I used to do in high school, and let’s just see what that looks like on camera? That’s what you get.

I want to ask you about Ali Wong. You both were voice actors in the animated series Tuca & Bertie, but this was the first time you were together, collaborating, acting, sharing scenes.

SY: Ali is tremendous. She holds so much power, so much presence. She’s just so dope. Playing against her was really fun because we only got specific moments in the earlier part of the run of really coming together. Each time we did, there was always this excitement where after we [would] finish that particular scene, we’re like, “Ooh, this is fun. There’s something here.” I couldn’t have asked for a better partner to do this with.

Steven Yeun

You’re from an immigrant family. You moved from Korea to Canada when you were four years old. Then you end up in Michigan. How did you find your way to acting, and then how did you message that to your parents and family?

SY: I don’t know how I found myself here, to be quite honest. I really do feel like a large chunk of my early childhood was me just trying to explain myself or just trying to feel visible. I think [a feeling of] being very conscious of being displaced follows me in my adulthood. I do remember I used to have this recurring nightmare where I would be walking down a hall going into a kindergarten classroom, and Freddy Krueger would be waiting for me on the chalkboard. It went away, which is really cool, but I do have a distinct memory of being dragged into a kindergarten classroom at four and just sitting in front of Play-Doh. It was this very isolating, very abandoned feeling that I think a lot of immigrant children can relate to. There’s an abandonment that I think is present in a lot of displacement in that way. I feel it started there. I spent a lot of time explaining myself and trying to get people to see me in a very specific way, in a way that I wanted to be rendered.

Growing up with that kind of chip, I found myself gravitating toward places where I could really perform — going to church and wanting to join the praise band. I remember, early on in high school, I wanted to be a SportsCenter anchor — it was just a place where I could be seen. It’s a strange thing, because this business that I found myself in, I don’t know if you’ll ever be seen, and maybe the business is actually about not being seen. I think I have to reconcile myself to that, which is fine. In college, I remember going to watch this improv show and just being like, Whoa, you can do that? I just took these steps, moved to Chicago, got a chance to move to Los Angeles, landed on this crazy show Walking Dead. I don’t know, I can’t really define anything, but I feel so lucky for this life. I wish I had this plan, but it never works out the way that I think it will. I’m very grateful to be here. It’s really wild.

That is luck. That obviously is talent, and it’s being in the right place at the right time and the right show at the right moment, but you have to be good to get that job. But your choices are great. You make really bold choices. I love that about you.

SY: I am making choices. I am saying no. I think for me . . . [the right thing will] just feel natural, like, “Oh, that’s the next story I have to tell.” Or it’s like Minari [where a script just] lands, and Christina [Chou, Yeun’s agent] goes, “Hey, I have this script written by your cousin.” I’m like, “What are you talking about? Who’s my cousin?” She’s like, “Isaac.” I’m like, “Oh my god, Isaac! My wife’s cousin.” We barely talked before [Minari]. We never talked about working together. I didn’t even know if Isaac was making things anymore. Approaching that script, I flailed about being like, “Please change it. I want to play the son grown up. Can we go back and forth in time? Can I not play it?” Then he’s like, “I think you’ve got to play this father.” I’m like, “I can’t. How could I play this father, this Korean dad? How could I do that?” The journey that took me on was incredible. I don’t know what it is, but I just keep being able to throw myself in a fire. I’m deeply thankful for that, as gnarly as it can be.