Acclaimed creators Guillermo del Toro and Scott “Kid Cudi” Mescudi reflect on crafting the worlds of Guillermo del Toro’s Cabinet of Curiosities and Entergalactic, their shared passion for horror, and using music to underscore emotional storytelling.

In the months before Guillermo del Toro won an Oscar for his first stop-motion animated feature, Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio, he would reiterate one common refrain during every public appearance and in every interview — animation is not a genre for kids. Rather, it’s an invaluable artistic medium, one as inherently cinematic as live-action, and one that is ideal for challenging storytelling aimed at adults. His passionate defense of the form manifests in numerous ways, among them his ardent fandom for projects that exemplify his argument, like Entergalactic.

The animated program from creator, executive producer, and star Scott “Kid Cudi” Mescudi is both a rom-com about an artist, Jabari (Mescudi), who falls in love with an up-and-coming photographer, Meadow (Jessica Williams), and an impressionistic ode to New York City — with a killer soundtrack to top it off. “I think that it’s a really tremendous piece of material,” del Toro says.

Mescudi is also a longtime fan of del Toro’s work, having seen the Mexican-born filmmaker’s English-language debut Mimic nearly 25 years ago. The two met for the first time at last year’s Annecy International Animation Film Festival, where del Toro unveiled a first look at his years-in-the-making passion project about a little wooden boy born into a strange and terrifying world. “That was a really big moment for me,” Mescudi recalls. “I remember texting my mom about meeting out there.”

For Queue, the two artists recently joined one another in conversation, not only about the inspirations behind Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio and Entergalactic but also about their love for the horror genre: Mescudi executive produced and starred in X, the recent hit horror movie from writer-director Ti West, while del Toro has produced his own eight-episode Netflix horror anthology, Guillermo del Toro’s Cabinet of Curiosities.

An edited version of the conversation follows.

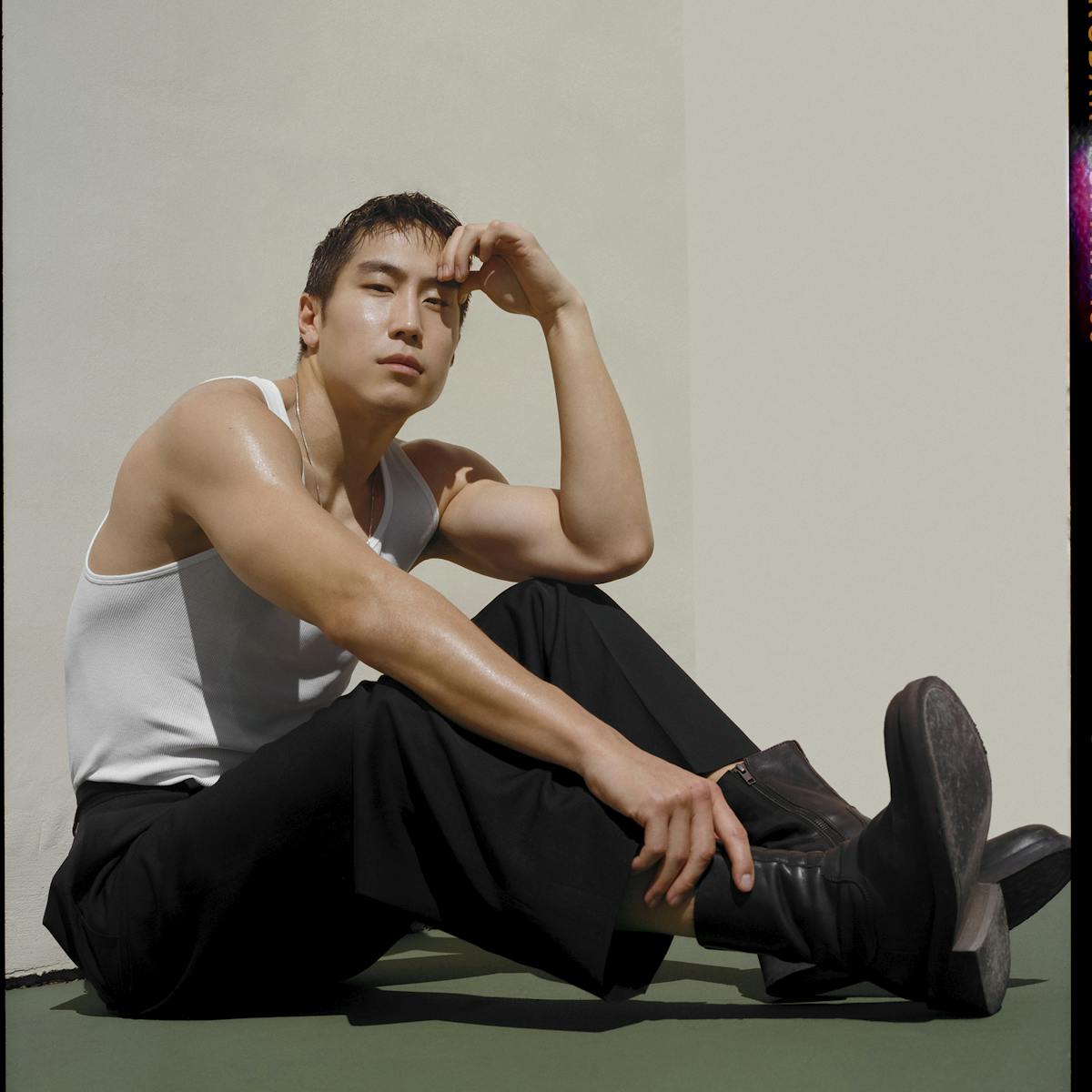

Jabari (Scott Mescudi) in Entergalactic

Entergalactic was based on my dreams and how colorful they are at times, but I wanted to make it still fit into reality. I didn’t want it to feel like fantasy.

Scott Mescudi

Rafael Motamayor: When were you first exposed to each other’s work, and what about it appealed to you?

Guillermo del Toro: I saw Entergalactic before Annecy, and I was blown away. [It took] advantage of animation in the way I understand it, which is that you don’t have to do skateboarding animals and fantastic creatures. You can actually make human experience deeper and more expressive. I think animation is a great tool for that. We met at Annecy, and I was just stanning him.

Scott “Kid Cudi” Mescudi: Just seeing how excited you were about Entergalactic really touched my soul, man. [It] made me feel really good about what we made, and we all worked really hard on it. That was the first real reaction from somebody watching it, outside of our camp. So that was a big deal for me.

Scott, do you have a favorite title by Guillermo?

SM: The first movie I saw of Guillermo’s was Mimic. I remember that movie rocking my soul. I’m a huge fan of horror. [At] seven years old, I think the first movie I saw was Night of the Living Dead. So I got in really early. [Mimic], the monsters and the horror aspect of it, was just something I had never seen before at that time. I became a fan immediately.

GDT: Mimic is probably the only horror movie [that] I made wanting it to be scary. I mean, all the other movies are reflections on horror, but they’re hardly horror movies. I think Blade II is horror action.

SM: Do you, in the future, see yourself doing something that’s more like Mimic, just like straight gore, more suspense, thriller?

GDT: I am much more at home producing those movies for other people than doing [them myself]. I always go to the metaphor, or the sort of poetic or weird, the more melodramatic. I tend to [lean toward] tragedy more than horror. But I love producing horror.

What appeals to you both about the storytelling potential of horror?

SM: I think there’s a lot of space to explore new realms in horror. I haven’t really seen myself in a horror movie. There are maybe a few: Night of the Living Dead and the remake in the 90s with Tony Todd. I’m writing a horror thriller right now, and I feel like there’s room to see more Black stories in horror. Jordan Peele is someone who’s at the forefront of that, and I feel like we’ll start to see more in the future. It’s a dream of mine to lead a horror movie.

GDT: I think horror is one of the most socially sentient genres because it’s an amplification of things that we feel in the real world. We elevate them to parable, but they are real. There’s a whole aspect of horror that is revealed when Jordan Peele grabs it and turns it on his ear and says, “Ooh, let me show you how I can view it.” I just saw a really great movie called They Cloned Tyrone by Juel Taylor. He uses sci-fi horror to talk about something very profound and funny at the same time.

Thurber (Ben Barnes) in the “Pickman’s Model” episode of Guillermo del Toro's Cabinet of Curiosities

I think horror is one of the most socially sentient genres because it’s an amplification of things that we feel in the real world. We elevate them to parable, but they are real.

Guillermo del Toro

What were your guiding principles in terms of visualizing the worlds you imagined?

SM: Entergalactic was based on my dreams and how colorful they are at times, but I wanted to make it still fit into reality. I didn’t want it to feel like fantasy. I wanted it to feel very much like, “Oh, shit, that’s New York City for real,” like this is a living, breathing place that we’re watching. And then working with the animators, working with Fletcher Moules, who was the director and the genius that helped bring this whole thing to life — it was really just about making something that was visually stunning, that made you feel like you were a part of a whole new universe. We spent a lot of time just trying to create the world of New York and trying to imagine what it would look like.

GDT: It’s a reality that pulsates between hyper colors, a sort of trippy, impossibly beautiful, and alive New York. I think people have to understand that the medium of animation is part of the message; the look is the story. Part of what makes Entergalactic so powerful is the formal decisions you guys made with that animation. With Pinocchio, I think the origin is the same as yours. I wanted to show what happens when you make a universal tale specific to your needs as a storyteller. The first day we started this project, I said to the entire team, “We’re going to make the best stop-motion movie possible.” And I really felt we could make a movie that fit between Pan’s Labyrinth and The Devil’s Backbone as a companion movie, but in animation. Animation should not just be a babysitter genre that just watches the kids for two hours.

I wanted to make a movie that was deeply felt and profound. And I think — maybe we agree on this, or not — that the way people watch animated characters is a lot more generously and empathically and profoundly than the way they watch actors. You sort of empty yourself into the beauty of the experience. Look, your movie, I put it on, and I was absolutely tripping. I wanted to watch it on IMAX. And preferably not entirely sober.

You have very different backgrounds with music. How do you find the key to integrating music and songs into your stories?

GDT: In my case, I like to try and cut the movie silently without score. Pinocchio is not a regular musical. The first half of Pinocchio is people singing, and the second half of Pinocchio is mostly fascist music that you hear through the loudspeakers [in Italy where the film unfolds]: marches for Mussolini, training camp music, radio. The singing sort of stops until the very, very end, and that was a decision that came from talking to Patrick McHale, my co-writer.

SM: I feel like music is that special secret sauce in movies that you don’t realize enhances the whole experience of what you’re seeing. With Entergalactic, the main goal was to make something that married the animation and the music together. I wanted to have music that narrated the story, but also didn’t push it too much. I didn’t want to have the narration giving away all the answers. I wanted the audience to still feel like they could follow along and enjoy it without getting the answers fed to them. So it was a fine line to walk when it came to writing the songs — just trying to make sure that they were vague enough on the details but gave you the tone and the feeling of each scene. I’m a very sensitive man, so I like to tell stories that talk about matters of the heart. Entergalactic was another way of me opening up my soul to the world.