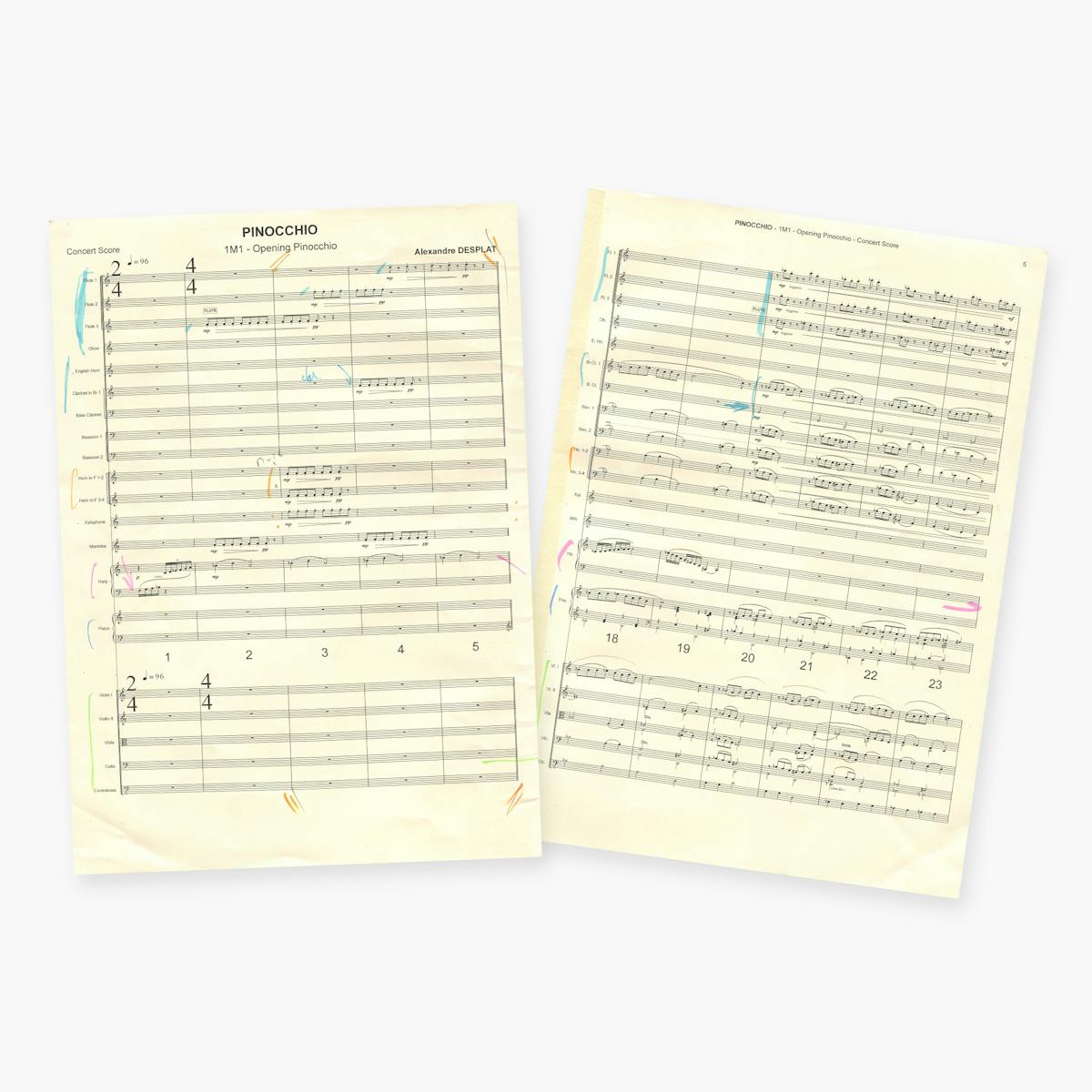

This excerpt from the forthcoming book Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio: A Timeless Tale Told Anew spotlights the dazzling artistry that brings the stop-motion adventure to life.

Although Gris Grimly’s rendering of the Pinocchio character in the 2002 book he helped illustrate initially prompted Guillermo del Toro to mount his own adaptation of the fairy tale, the filmmaker always knew he would need to modify the design to bring the puppet to three-dimensional life. With that in mind, he turned to one of his go-to creative partners, creature designer and illustrator Guy Davis, for Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio.

Back in 2012, when del Toro was first collaborating with Davis on concept art for Pacific Rim, he also hired the artist to tweak his little wooden hero’s silhouette and to rework some earlier character designs del Toro had commissioned from concept artist Rustam Hasanov. “We wanted to move away from design that you normally associate with animation,” del Toro says. Adds Davis: “We didn’t want the character to have that crooked, angular, too-cartoony feel to it.”

Davis began by modifying the shape of the character’s head to make it less round, while also altering the proportions of the puppet’s limbs and torso. “Guy extended and changed the length of the legs, which creates a different stance,” del Toro says. “We reproportioned the body, made it more of a teardrop shape. And we made Pinocchio asymmetrical because Geppetto carves him when he’s drunk — he starts with the ear and his hair, and he is really careful with that. Then, he finishes him quickly.”

Davis also revisited Grimly’s designs for several other principal characters, including Geppetto, and he took on the story’s more fantastical creations as well, including the Wood Sprite and Death, inventions of del Toro and his co-screenwriter Patrick McHale. “I didn’t want them to be flesh-and-blood,” says del Toro, who imagined the two as masked sisters. “They’re both inscrutable.” Though Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio would not go into production until years later, the early design work played a crucial role in establishing the film’s overall aesthetic.

Once the project was green-lit in 2018, Davis spent time at the Portland, Oregon offices of ShadowMachine — the company founded by the film’s producers Alex Bulkley and Corey Campodonico — working to refine his designs. “This is a story about puppets, acted by puppets,” del Toro says. “You have to believe in them as characters. We wanted design that told the story.”

That approach applied to all the characters, though it is perhaps most immediately evident in sly trickster Volpe. “As the conductor of this carnival, he is incredibly flamboyant,” says co-director Mark Gustafson. “Some of his design elements are based on a fox — his hair shoots up almost like ears, but he’s kind of the devil in a way, and his hair [resembles] horns too. He corrupts Pinocchio. He draws him away from Geppetto and into all the fun and sin of the carnival.”

By contrast, the Podestà is far less exaggerated — the filmmakers felt he should be intimidating from the moment he first appears onscreen as the town blacksmith, signaling his future as a Fascist official. “We created a very angular face, almost like bone with skin stretched over it, and gave him a very small pencil mustache,” del Toro says. “What we wanted to remain expressive were his eyes.”

This notion of character being determined by design also extended to Davis’s work on the animal protagonists. Sebastian J. Cricket presented an interesting challenge because Davis needed to craft the character in a way that would suggest his intelligence while also retaining the features of a real cricket. “With the human characters, you could do a lot more with the eyebrows or the shape of the mouth,” Davis says. “Cricket is so small, I was trying to come up with something that would be simple enough to read onscreen. The eyes were very simplified, and the mustache, which represented his mandibles, helped convey when he was feeling sympathetic or angry.”

Spazzatura, Volpe’s henchmonkey, also needed obvious simian characteristics. Davis gave the monkey a noticeably wiry frame that made him look both suspicious and ill-treated. “He’s still far removed from what a real monkey looks like, but you could feel some sympathy and some sadness with him,” Davis says. When developing concepts for the story’s imposing dogfish, Davis applied a similarly empathetic lens. “It’s a creature that’s trying to eat everyone, but it’s lived so long that it’s just bored and miserable,” he says. “I [wanted it to have] a little bit more character than just a mindless killing machine going through the ocean.”

Although Davis’s designs would serve as the foundation for the film’s puppets, exploratory work had begun years earlier at England’s Mackinnon & Saunders. The world’s leading company specializing in pup-pets for stop-motion productions, Manchester-based Mackinnon & Saunders had crafted memorable characters for Tim Burton’s films Mars Attacks!, Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride, and Frankenweenie, as well as Wes Anderson’s Fantastic Mr. Fox. “They are the masters, and they do things that other puppet builders do not have the patience or expertise to do,” says producer Lisa Henson. Echoes del Toro: “They are the best in the world. The starring roles of the movie needed to be fabricated by them.”

This is a story about puppets, acted by puppets. You have to believe in them as characters. We wanted design that told the story.

Guillermo del Toro

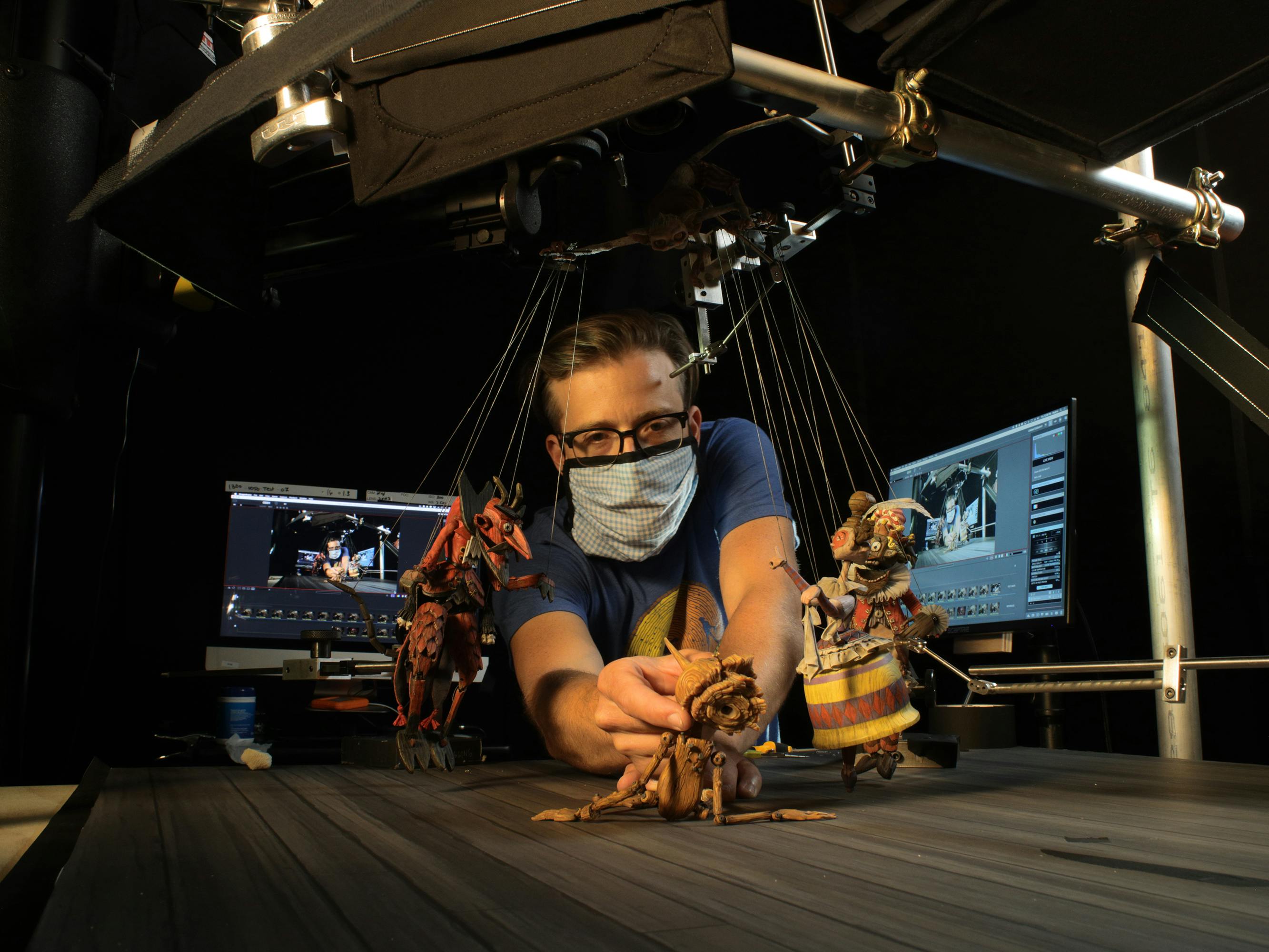

For Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio, del Toro wanted the puppets to be constructed with mechanical faces, meaning that beneath their silicone skin would sit a complex system of interlocking paddles and gears the animators could use to manipulate their features and create performances. He wanted to limit the use of rapid prototyping, or replacement animation, which uses a 3D printer to create multiple faces for a puppet, each with a different expression that the animator applies for specific scenes. “Replacement animation creates a digitally printed catalog of faces that is very wide but robs the animator of the thousandth and one choice that they would make if they were going to physically animate the puppet,” del Toro says. “There is an old art form in Japanese theater called Bunraku where the puppet, on a black stage, fuses with the actor manipulating it. In stop-motion animation, there is the same kind of sacred bond between the animator and the puppet that breaks when you print the faces.”

Georgina Hayns, Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio’s supervisor of puppet fabrication, played a hands-on role in determining how best to execute del Toro’s vision. Hayns had worked at Mackinnon & Saunders and spent just over 12 years at acclaimed stop-motion studio Laika on projects including Coraline and The Boxtrolls. In partnership with the film’s animation supervisor Brian Leif Hansen, Hayns helped guide the intricacies of the fabrication process.

“As the person heading up the puppet build, you really want to keep the integrity of what the director wants the look of the movie to be,” Hayns says. “Our job is to try to problem-solve, to make these designs work as puppets and get the performance that they need.” Adds Hansen: “We were working closely together with Mackinnon & Saunders, and then the first animators started to come on. We started getting puppets in, testing them to see if they were working, just making sure that the puppet looks nice when it’s doing the action that it’s required to do in the film.”

Del Toro and his partners did come to realize that some rapid prototyping would be necessary — for Pinocchio in particular. The hero needed to appear as though he were made from wood, and creating his face from 3D-printed hard plastic would be an easier way to achieve that effect, rather than fashioning it from silicone, the method used for most of the other characters. “If we tried to do a mechanical head on Pinocchio, you wouldn’t believe it,” Hayns says. “A silicone head skin that sits over mechanics wouldn’t look like wood anymore, but it doesn’t jar that he is created using a different animation technique because he’s so different from the other characters.”

With Mackinnon & Saunders constructing the principal pup-pets in England, puppet sculptor Toby Froud and numerous other artisans working at ShadowMachine’s Portland offices began crafting the other key characters, including Carlo, the Podestà, the Wood Sprite, Death, and the dogfish. Additionally, a second-unit puppet department was created in Guadalajara at Centro Internacional de Animación (CIA), an animation studio nicknamed el Taller del Chucho (literally The Mutt’s Workshop) that del Toro founded in 2019 in central-western Mexico. There, the filmmaker hired award-winning stop-motion veteran and founder of the puppet-making company, Humanimalia Studio, León Fernández to build Death’s Black Rabbit undertakers, which Davis had designed with elongated faces, exposed rib cages, and skeletal hands.

For his 2011 short film, Mutatio, Fernandez won the Rigo Mora Award at the 26th Guadalajara International Film Festival — a prize named in honor of del Toro’s longtime creative partner, who died from respiratory failure in 2009. After co-founding special effects makeup house Necropia with del Toro in 1985, Mora made numerous stop-motion animated shorts and taught at the University of Guadalajara, among other institutions. His students, in turn, trained some of the animators who served as part of Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio’s second unit. “This is a way to bring that cycle to a close,” says del Toro. “It really is a very beautiful generation. Rigo and I, we were better known for our enthusiasm than for the quality of our dance. These are top-notch dancers.”

As the puppets were being fabricated, del Toro and Gustafson continued building the team to support their ambitious vision. Like Hayns and Froud, many of the subsequent hires were acquainted with one another from previous stop-motion productions. “It’s a relatively small world,” Gustafson says. “When this opportunity came along, I said, ‘I want to assemble the dream team,’ and we went out and got them.”

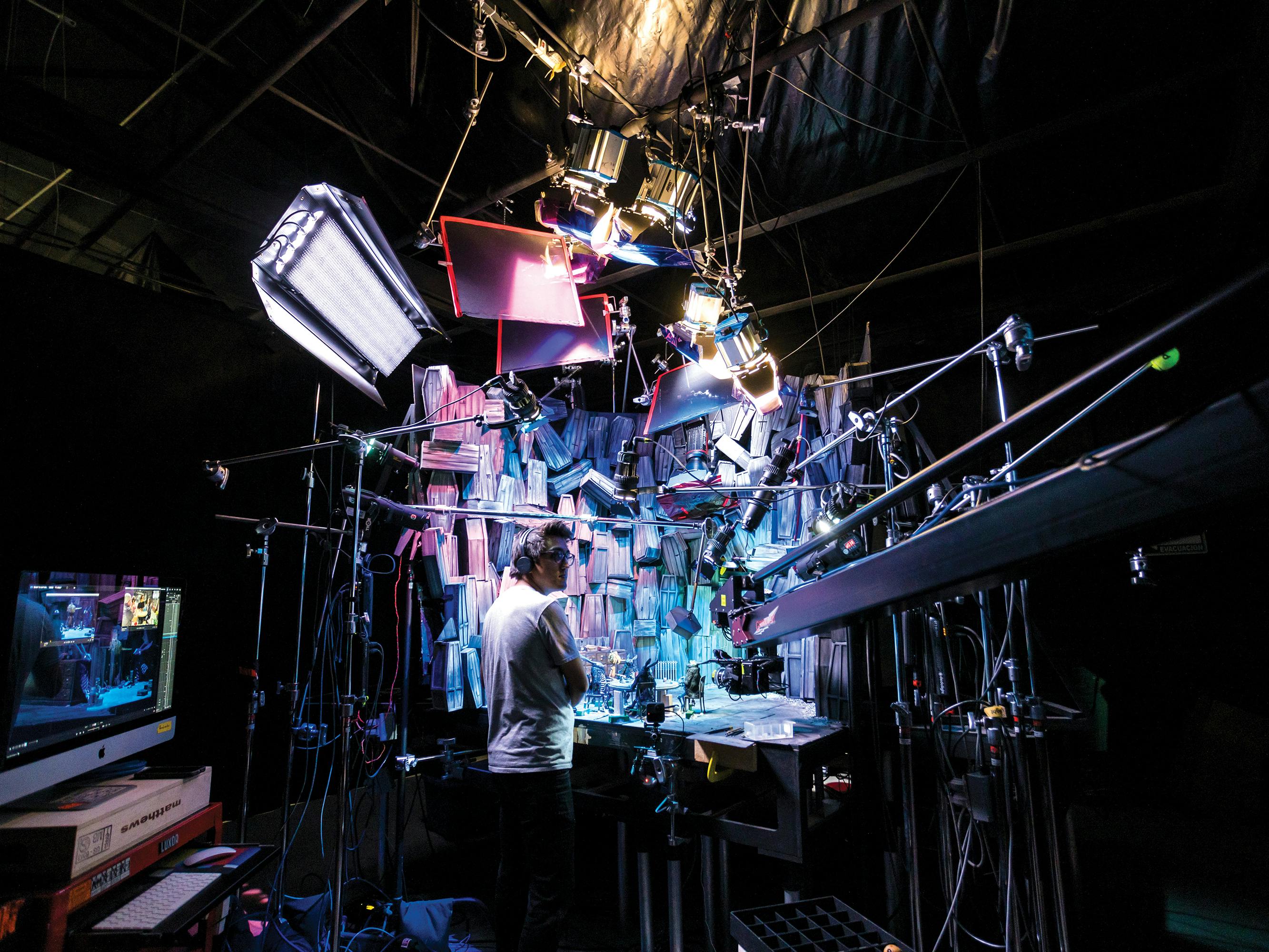

Acclaimed cinematographer Frank Passingham, whose credits include Chicken Run and Kubo and the Two Strings, joined the production as director of photography, while Robert DeSue (Missing Link, Kubo and the Two Strings) signed on as art director. Del Toro’s longtime collaborator Davis would become Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio’s co-production designer with Curt Enderle, whose credits include Wes Anderson’s stop-motion film, 2018’s Isle of Dogs.

One of the early priorities for the department heads was to develop the color signatures for the film with the directors. “We really wanted to speak Guillermo’s language because he refers back to things that he’s done before, so we chose colors that were in keeping with that idea,” Enderle says.

Together, they settled on warm gold and amber hues for the village setting where both the town church and Geppetto’s home are located; oranges and greens for the traveling carnival; red for the movie’s Fascist camp; and cool blues and purples for the underworld of Limbo, colors that were also used for the dogfish scenes. In many cases, the palettes for each environment were also applied to the puppets themselves: Volpe hews to the carnival colors, while magical characters like Cricket, the Wood Sprite, Death, the dogfish, and even the Black Rabbits share a similar paint scheme. “They all have the same otherworldly blue-violet, purple skin because they are all related,” explains del Toro.

For Pinocchio, the filmmakers selected a distinctive shade of brown. “Making sure that Pinocchio had a singular color was super important,” DeSue says. “We felt like no other wood could even get close to having that type of grain or that type of texture. But we did take some license. He’s pine, and pine is generally a lot yellower, but Pinocchio leans a little browner.”

Along with overseeing the puppet builds, Hayns super-vised the creation of their costumes. After researching clothing from early twentieth-century Italy, she filled mood boards with reference images and swatches of fabrics that would meet the animators' needs. “What we’re looking for is a fine-weave fabric with a stretch, because if you don’t have some stretch in the fabric, it will hinder the puppet’s movements,” she says.

The production used a variety of material, from linen to leather, creating cable-knit sweaters and scarfs for Geppetto, Carlo, and Candlewick, to pair with woolen trousers and ankle boots. Volpe was given an eye-catching costume that included an embroidered green vest, striped pants, and a long overcoat trimmed in fur, complemented with a fox-head cane. The Podestà was dressed in the paramilitary style adopted by members of Mussolini’s National Fascist Party.

Every garment was treated to look weathered with age or stained with sweat — costume makers would frequently use sandpaper to break down brand-new items. Wires were sewn inside garments to give the animators more control over the costumes. “Putting wires in the fabric, we are able to manipulate it to simulate the wind, simulate movement,” del Toro says.

During the costume-development process, one of Hayns’s counterparts at Mackinnon & Saunders sent her a sample fabric for the red-and-white striped pants that Spazzatura wears, and the tiny swatch proved to have an outsized impact on the production. “She’d stitched it together with a slightly uneven line in it,” Hayns says. “I looked at it and said, ‘That is beautiful. It’s perfectly imperfect.’”

For Hayns, Davis, Enderle, and DeSue, that notion became central to the film’s visual philosophy, influencing even the wood grain on Pinocchio’s face and body. “We decided that was what we wanted lines to look like in our film,” Hayns says. “If a house is built, it’ll have a wall with a line [that’s not entirely straight] — perfectly imperfect. We sent a picture of this one piece of fabric around to every department as a pivotal reference.”