Elizabeth Debicki talks through the beauty and challenges of playing one of the twentieth century’s most beloved people on The Crown.

Star quality: It’s that ineffable trait that makes an actor pop off the screen. When a performer has it, you become entirely absorbed by the characters they play, the scenes they seem to so effortlessly inhabit. Anyone who’s witnessed actor Elizabeth Debicki’s astonishing work as Diana, Princess of Wales in The Crown knows that the Australian actor has star quality in spades.

Taking over the role from Emma Corrin, Debicki brings a more mature Diana to the fifth season of creator Peter Morgan’s prestige drama, which unfolds during the early 1990s. It’s a period when Diana is attempting to chart a new and more independent course for her life, but every effort she makes to have her voice heard — whether cooperating on a covert biography or granting a candid interview to the unscrupulous Martin Bashir (Prasanna Puwanarajah) — only brings more intense scrutiny. The public spotlight is unrelenting.

Portraying one of the twentieth century’s most iconic women, Debicki understood that her performance would be carefully examined. “It’s an enormous amount of pressure as an actor,” she says, “because you don’t usually have to play [a role] that someone else has just played so excellently. Then, of course, there’s the responsibility that you feel to do this person’s legacy justice. They’re two quite different pressures, but they both work in tandem when you start doing this job. That was, at times, pretty overwhelming.”

Fortunately, Debicki isn’t one to shy away from a challenge. She came to The Crown after delivering a decade of impressive performances dating back to her breakthrough in 2013’s The Great Gatsby. Notable turns in television (The Night Manager) and film (Widows, Tenet) followed, showcasing her versatility and range. “You have to sift through what Diana’s become — because people need her to become a certain representation or symbol — to get to the real-life person,” says Debicki of how she began to practically approach the creative challenge that lay ahead of her.

Debicki shared with Queue her personal recollections of the former Princess of Wales, the experience of inhabiting Diana’s psyche for so long, and how one well-timed glass of champagne helped launch her career.

An edited version of the conversation follows.

Elizabeth Debicki

Krista Smith: I first saw you in Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby, playing Jordan Baker, the incredibly chic professional golfer. Your co-stars were Leonardo DiCaprio, Carey Mulligan, and Tobey Maguire, and you were the discovery in that film.

Elizabeth Debicki: I was out of drama school for, I think, two months when I got to do a screen test for Gatsby. I was in Melbourne where I’d just finished school. I went to [an] almost religiously theater-based training school. The methodology was very physical, lots of clowning, lots of Shakespeare and Chekhov. We were told very clearly, “You are lucky if you get a job, period, and it will only be in theater,” which is what I was aspiring to at the time. So, I didn’t know how to do a screen test. I went in there, and I was nervous as hell. There was a camera and a lovely reader who read very, very quickly, which made me drop my lines. I mean, I felt like I did it 12 times. I probably did it four times. Somehow, that [audition] tape magically found its way into Baz’s [hands]. I honestly don’t even know how you get Baz to sit down, so it was incredible that he sat and watched it. And then they flew me to L.A., and I did a screen test with Tobey at the Chateau [Marmont], which was one of the strangest and most memorable experiences of my life.

I’d never been to L.A. before. Tobey and I read the scene, Baz is filming us, and my hair’s in this fake little bob. We staged the whole thing. We go around the table, and we sit on the couch. He’s just following us like a puppy dog with this camera. Then we go to the bedroom and there’s another scene. I’m lounging around on the bed, and I’m just talking the whole time. I have no idea what accent I was doing. It went for about an hour and a half. The entire time I thought, I literally have nothing to lose. It was an incredibly freeing thing because I thought, I’m probably never going to see these people ever again. I went downstairs, and I remember thinking, We’ve got two hours or something until I have to leave for the airport. I’ll have a glass of champagne in the sunshine. I think I was 20 at the time. Is that legal?

Elizabeth Debicki

[DIANA] WAS . . . STILL ACTIVELY IN MY BRAIN. I WAS THINKING ABOUT HER CONSTANTLY.

Elizabeth Debicki

In the States, probably not.

ED: That’s so funny. I was like, “I’ll have a bottle of your best champagne, sir.” So I sat there, with this glass of champagne, and on the balcony of where I’d done the test in the room, suddenly [up] pops Baz’s head and he just looks at me and he does this little point. Then from behind him, Leo comes and stands there, so Gatsby-esque. I remember seeing Baz and Leo and Tobey’s faces as this triptych. I just waved at them and then I retreated. I got the job about a month later, but I went back to Melbourne absolutely convinced that I wasn’t going to get the job. It was amazing when I actually did.

You just wrapped Season 6 of The Crown. Has Diana left your body at all, or will that take some time?

ED: I honestly don’t know. Two years is a long time to play the same role. I’ve never done that before. It’s been quite radical for me to just think I’m going to rest. It’s like I don’t know how to do it. So, I’m trying to teach myself. And in the process of that, I’ve been thinking about how much of that role is in me. When does it leave, and has it already begun? I wonder if we don’t sort of gradually say goodbye.

When I finished Season 5, I knew I had to hold that space open, even with a hiatus in shooting, to just go straight back in. That person was absolutely still actively in my brain. I was thinking about her constantly. This has been a gradual handing over. I’m starting to get these funny pangs. My phone and my laptop and everything are full of imagery of her; when I look at it, I get this funny, sad jolt. I guess the process of her no longer being the most active thing in my brain is starting.

Elizabeth Debicki

You were born in the 90s. When was the first time that you actually were aware of Diana?

ED: I always say that it was [during] her funeral that I became conscious of her, like a lot of people my age. I was seven. It was watching my mother watch the funeral in our little suburban house in Australia, and seeing my mother so overcome by sadness. You remember quite distinctly as a child when you see your mom cry like that. You don’t always understand what’s going on. I remember sitting on our shag pile carpet, my legs crossed, watching the funeral and obviously not really knowing what was going on, but really feeling my mother’s grief about this event, and then probably getting an explanation about it. Prior to that, she was always on the front cover of all our trashy Australian rags, Women’s Weekly and all that. So, [I] probably saw her face every time I was at the supermarket. But [the funeral] was my first conscious memory of understanding this person existed. And [I remember] watching the boys as well, because I was so close to their age, and understanding that this was a funeral, that it was somebody’s mom. That was probably the entry point. Of course, that was the point of so much grief for so, so many people.

This series does something we’ve never seen, changing a cast every two years. Emma Corrin brought Diana into the timeline beautifully. When that baton was passed, was there any dialogue between the two of you about it?

ED: There was no conversation. I could have reached out to them, but I did not at the time. I did post-shooting one season. When I did, of course they are just the loveliest human being. But in order to do it my way, quite basically, I just thought, I have to find ownership over this and create it from an imaginative place. That was a lot of clawing back preconceived ideas and pressures that I was putting on myself, to figure out how do I create [this character] not from too much of an outside-in process and more of an inside-out process? Which is a fiendishly difficult thing to do when you have so much outside available to you.

Elizabeth Debicki

WE ALL HAVE A RIGHT TO PRIVACY, WHICH IS TAKEN AWAY BY FAME. IT'S A KIND OF DEAL THAT IS MADE.

Elizabeth Debicki

You did beautiful work in this role, and it’s all these pieces — the movement and the voice and the costumes are helping to bring to life images that are burned into our collective consciousness. I’d love to hear how you as an actor put all of those things in the blender, and what that experience was like.

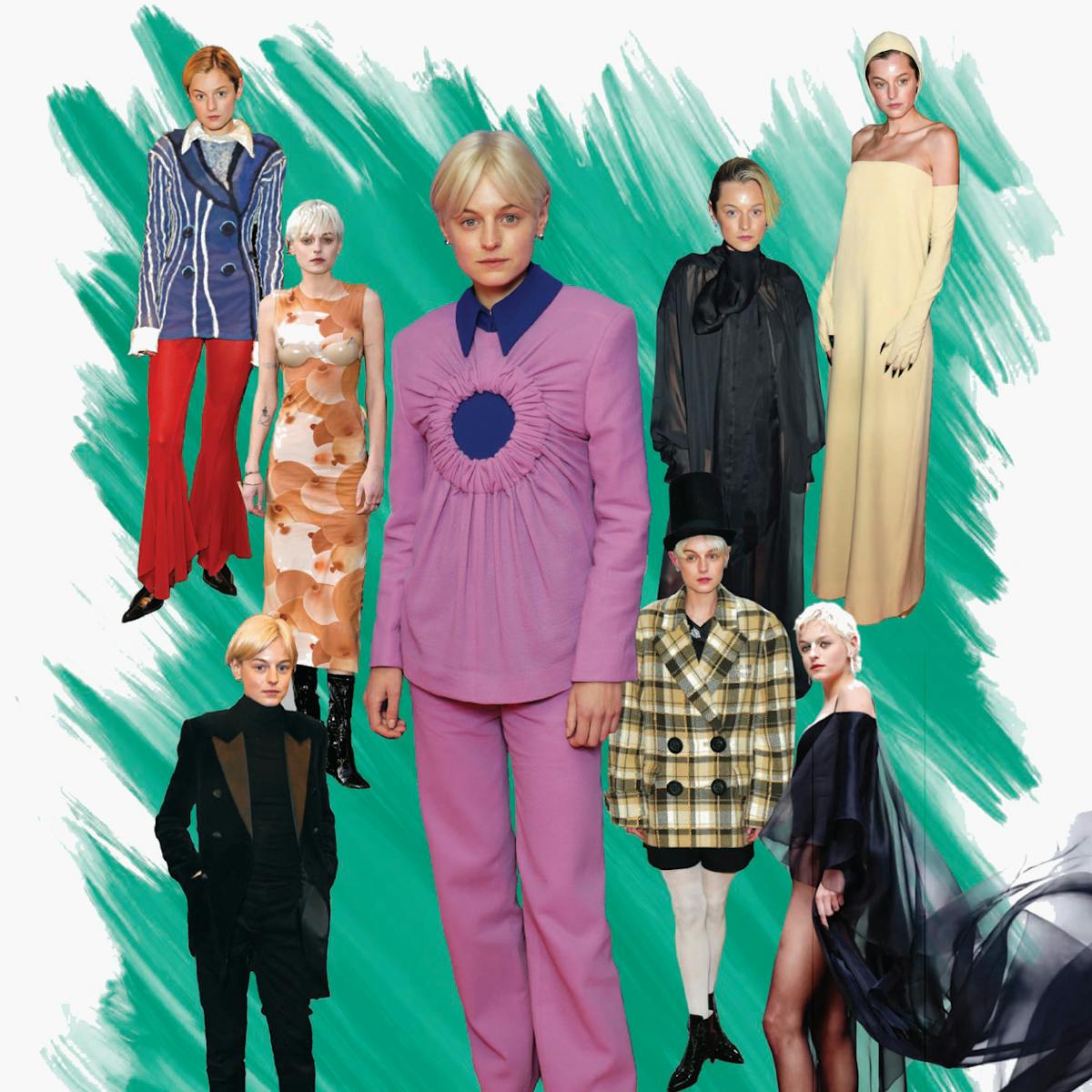

ED: I did a lot of homework to try to understand the layers of the imagery. It was daunting because, on a purely human level, I look at pictures of her and I think she’s extraordinary. I’m standing there in my tracksuit in the costume room looking at these mood boards, thinking, There’s no way in hell. I think I’ve always been able to stand in two roads, and one is the actor interpreting, and then the other is just sort of the normal plebeian person looking at this woman thinking, You’re so beautiful, and just so luminous, and so cool. [Sidonie] Roberts, the costume designer, would have to drag me back into the actor-interpreting space because otherwise I’d sit there and go, I can’t wear those shorts; I don’t know how to do it. She just never had a bad fashion moment. And who else has ever done that? The clothes dictate the journey you’re going to go on in that scene with that role. When I would put on a long Cockney skirt and a big cricket jumper or something, it told my body that it could rest, and that was going to dictate how open I could be. If you’re putting a big gown on and you’ve got a tiara on your head, the body responds to that. It knows that it’s restricted, and it’s going to be observed. It’s interesting how responsive it is in that way, and you get to manipulate that as an actor.

If you take the revenge dress as an obvious example of that, it’s almost like there’s the shell, which is our quick imprint of that moment. I have to understand what the shell is constructed out of, like the physical kind of dress, and then penetrate it deeper to start to understand the psychological fabric of it, and how that’s impacting the muscularity of the person in the moment. I was fascinated by her luminosity. The ferocious, physical forward motion of that moment is so triumphant, and what it’s concealing is a person’s real, human pain. It’s a fascinating juxtaposition, and it’s all housed in that one imprint. I could never get over the confidence with which she spills out of that car and the way she puts her hand out. It’s so forward and beautiful and she’s so there, and it really moved me.

The series really exposes the relationship between the press, celebrity, and fame. It’s this toxic relationship, but Diana was able to have so much agency within this constant scrutiny and the cameras. Did it change your perspective on fame or the media?

ED: I think it did. I have very dear friends who are successful in this business and one of the prices they pay is that constant recognition. I’ve worked a lot and I’ve never had to deal with that. I’ve been in situations with friends who do, and you understand where it comes from, but I can see how that wears on a person. I’ve always been wary of it, thinking that we all have a right to privacy, which is taken away by fame. It’s a kind of deal that is made. Sometimes it’s made without the person realizing, or perhaps they thought they could control it, but it becomes

unmanageable. So playing that role and experiencing, in an imaginative sense, how painful that is to have your privacy taken away from you, one of the things that really struck me is how quickly people’s relationship to you as a thing to be observed takes away the fact that you are a person. I could be standing on a street waiting for someone to call, “action,” and half a meter away, someone would be standing there with their iPhone. I could look straight into the phone, and they [wouldn’t] blink. I’d be terrified to do that to someone. With phones and social media, there’s this desire to capture the person, so you somehow possess them. It’s unimaginable what would’ve happened if the story we’re telling took place 20, 30 years later.