The director returns to his native Mexico with his latest masterpiece.

There’s a famous saying in Mexico that goes, “The Three Musketeers are not the same 20 years later.” The phrase refers to the toll time takes on the physical and emotional vitality of the characters created by Alexandre Dumas — Porthos, Athos, Aramis, and D’Artagnan — in the sequel to the classic adventure novel. It suggests that youth will always be more valuable than seniority.

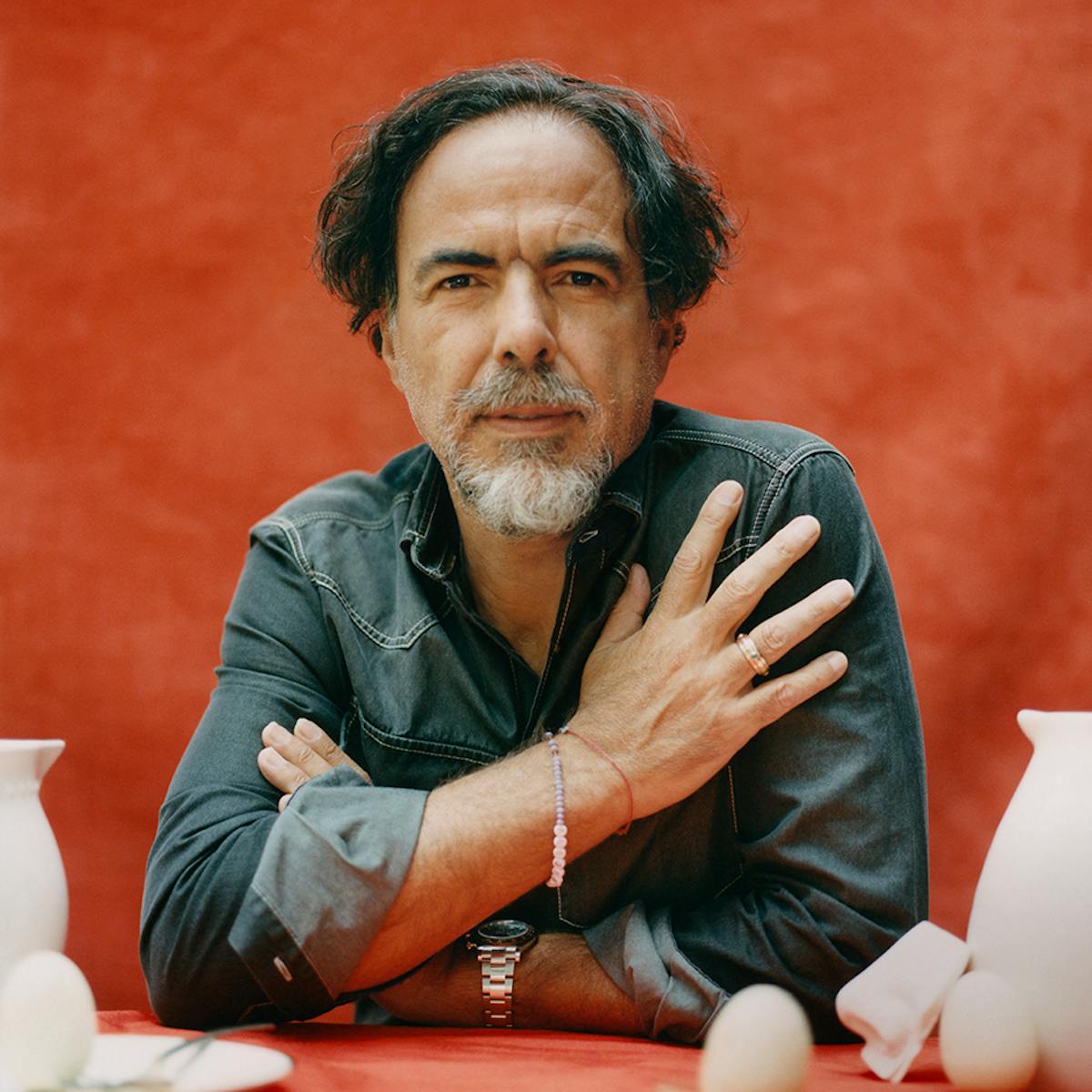

One of Mexico’s greatest filmmakers is the living embodiment of that notion’s fallacy. Twenty-two years after his searing debut Amores Perros (Love’s a Bitch), Alejandro González Iñárritu returns to Mexico for his latest movie, BARDO, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths, arguably his most accomplished work to date. Unlike The Three Musketeers, over the last two decades Iñárritu has seemingly managed to hold back the hands of time. The grays in his curly, dark hair are directly proportional to the talent and maturity that have permeated his career following Amores Perros. In addition to the prizes he’s won and the avalanche of laureate adjectives he has earned film after film, Iñárritu is now a titan of modern cinema with BARDO, dissecting both frustrated desires and death as part of a natural path in our earthly experience, as few filmmakers have.

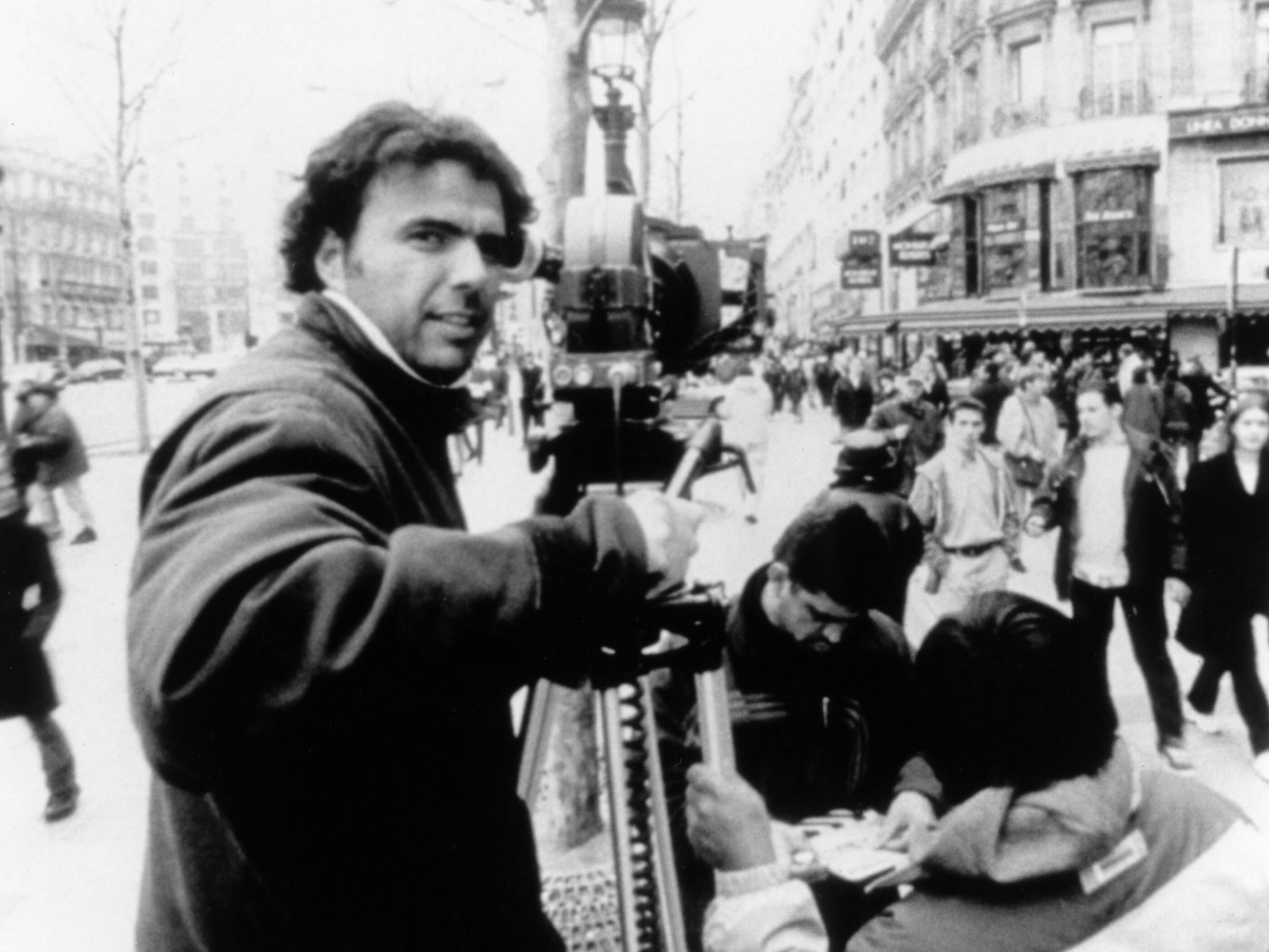

Iñárritu’s cinematic success was both immediate and profound. Already a well-positioned name in the creative universe, thanks to his work as a radio broadcaster and producer at Televisa — Latin America’s largest television network — he unleashed a hurricane with his first film, 2000’s Amores Perros, which became a social and cultural phenomenon without precedent in Mexico. A new millennium had begun with the most significant political metamorphosis in the country’s history, when a candidate from the opposition party was elected president for the first time in more than 70 years. Iñárritu and his co-screenwriter Guillermo Arriaga grasped the political circumstances of that time; Amores Perros acted as an autopsy of the decaying dreams of a population that was undergoing the breaking of social paradigms. The three stories in the movie questioned Mexican values and fears, which were so deeply rooted that they could be thought of as each color in our flag: motherhood, aspiration, and family. As seen through the film’s lens, these societal pillars become mortal sins.

However, there is another key aspect in the conceptual soul of Amores Perros: Mexico City itself as the central protagonist. The country’s capital is captured with its grayish avenues and traffic bottlenecks, its biblically scarred slums juxtaposed against upscale neighborhoods with grizzly secrets hidden behind each door. Perhaps not since 1950’s Los olvidados (The Young and the Damned) have we seen Mexico City portrayed as such a powder keg, populated with characters that can do little more than be born, grow up, and die in this urban chaos.

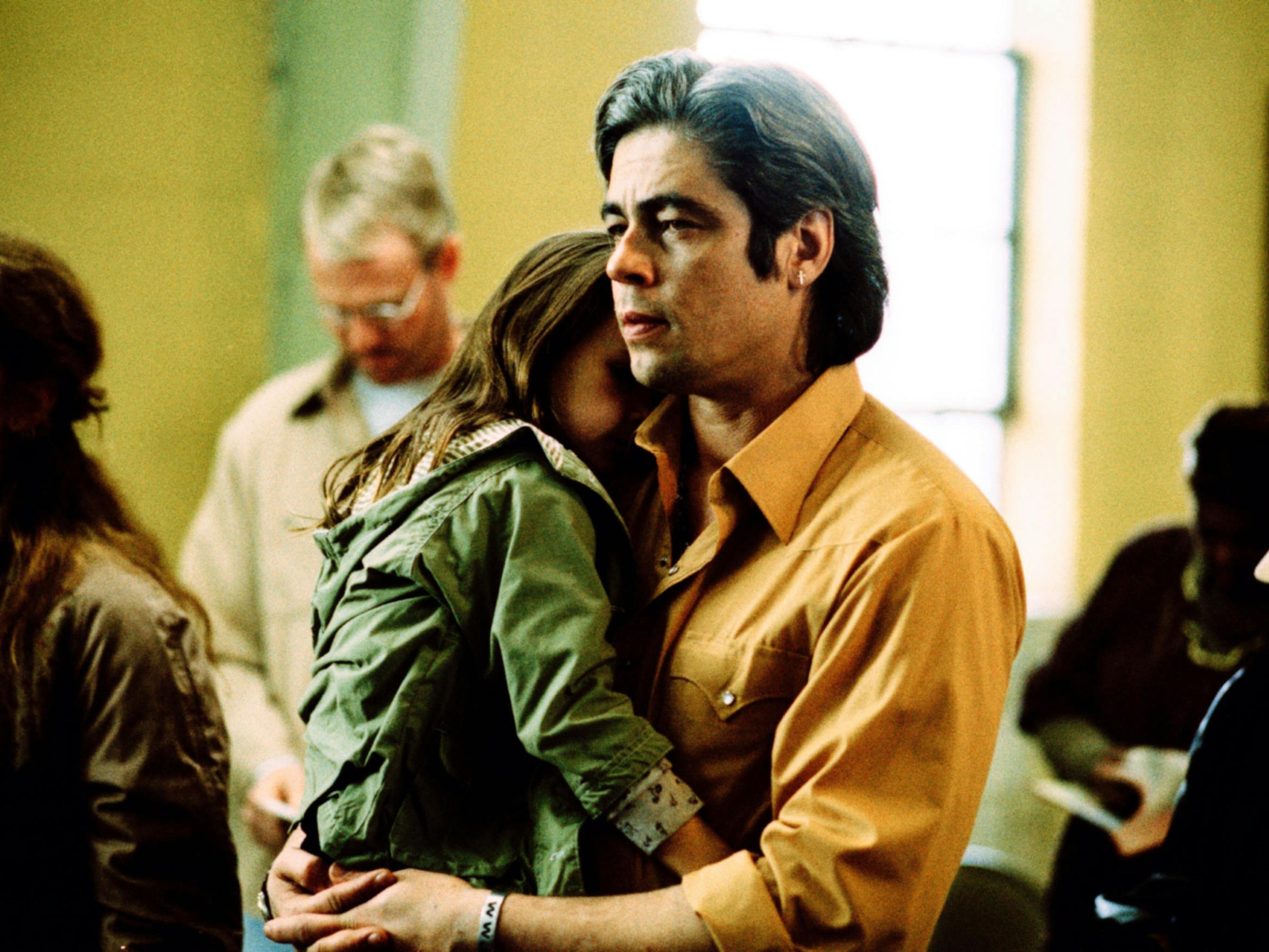

The search for our place in a certain time and space has been Iñárritu’s motif throughout his career. His films are existentialist odysseys that explore the often painful consequences of our attempts to find the roles we play in our own lives. In 2003’s 21 Grams, in which a freak accident brings together three strangers, Naomi Watts’s grieving mother Cristina notes, “Whoever looks for the truth deserves punishment for finding it.”

In 21 Grams, also co-written with Arriaga, death becomes the touchstone for defining our place in the universe. However, in 2006’s Babel, which concludes Iñárritu’s “Death Trilogy,” coincidences and language weave together the intersecting destinies of four different families from around the globe.

Iñárritu’s preoccupation with life and death continues with 2010’s Biutiful, starring Javier Bardem as a terminal cancer patient seeking to leave the world on his own terms. Iñárritu delves into mournful apologies, this time from the perspective of a low-level criminal wrestling with guilt, suffusing his tragic tale with a hint of surrealism. In 2014’s Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance), meanwhile, Michael Keaton’s Riggan Thomson, whose fame was fueled by playing a superhero in the 90s, ruminates on his professional legacy, fearing his comic book celebrity will forever overshadow his more serious accomplishments long after he’s gone. Like many of Iñárritu’s protagonists, the actor is in the throes of existential crisis, unable to find peace in any facet of his life; he can’t understand that the first step to reconciliation in a personal war is to make a truce with his past. Finally, in Iñárritu’s masterful historical epic, 2015’s The Revenant, revenge is a sort of sacred relic that provides hopeless nineteenth-century frontiersman Hugh Glass (Leonardo DiCaprio) with a divine purpose in the wake of his son’s murder, even if it can never again make him whole.

With Birdman, which earned four Oscars including Best Director and Best Picture, he and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki created the illusion that the entire film unfolded as one continuous shot. Over his career, Iñárritu has distinguished himself not only as a gifted visual stylist and skilled technical craftsman who is keen to boldly experiment with form, but also as a great intellect willing to probe some of life’s greatest mysteries through his work.

BARDO showcases both Iñárritu’s facility for existential comedy and his exemplary technique with a tale set once again in Mexico City — though it is now the present-day capital city, rather than the turn-of-the-century metropolis in Amores Perros. When Silverio Gama, a renowned journalist living in Los Angeles, wins an international award, he voyages back to his country of origin. Upon his return, he faces a crisis that forces him to revisit past phobias and his own existence. As Gama, the filmmaker cast Daniel Giménez Cacho (Y tu mamá también), one of the modern pillars of Mexican cinema, with Argentina’s Griselda Siciliani (Sin código) as his wife.

Iñárritu wrote BARDO with an old friend, Nicolás Giacobone, with whom he previously co-penned the screenplays for both Biutiful and Birdman. But the movie’s credits also include such prominent new collaborators as Mexican production designer Eugenio Caballero, an Academy Award winner for his work on Pan’s Labyrinth and nominee for the film Roma (acclaimed dramas from Iñárritu’s longtime colleagues and close compatriots Guillermo del Toro and Alfonso Cuarón). Mexican costume designer Anna Terrazas (Rudo y Cursi, Roma) also joined the team, as did Iranian cinematographer Darius Khondji (Se7en, Uncut Gems), shooting BARDO on location in Mexico City in 65mm.

Through Silverio Gama, Iñárritu and Giacobone venture to imagine — or dream — the familial, social, and cultural confusion of returning to a house that doesn’t feel like home. The migrant who wanders between two lands. The film’s very first scene, where a man jumps across the sand of the border desert, perfectly exemplifies a phrase from Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being and the very existence of Silverio: “Anyone whose goal is ‘something higher’ must expect someday to suffer vertigo.” Gama, after almost two decades away from Mexico, returns to his city and, there, under surreal circumstances, confronts himself, his family, and every inch of his past.

Narrated in a kaleidoscope of everyday anecdotes, BARDO, whose meaning could be interpreted as the Tibetan Buddhist term for limbo, is a metaphor for the state of the film’s protagonist, Iñárritu, and all of us who have left our childhood homes and landed in a life completely different from the one we were raised in.

Iñárritu’s intention is to give Mexico City a starring role. Unlike Amores Perros, BARDO allows the city its own timeless ecosystem. Dream sequences reinterpreting the Mexican-American War’s Battle of Chapultepec and its “boy heroes” blossom inside Chapultepec Castle. The California Dancing Club (one of the most emblematic tropical music ballrooms of twentieth-century Mexico City) is home to a bombastic scene to the rhythms of David Bowie, and on the club’s rooftop, Silverio says: “How beautiful this ugly city is, don’t you think?” Finally, the most ambitious sequence of BARDO was filmed in the heart of Mexico City’s downtown: Silverio walks among hundreds of bodies, falling dead on the street, then wanders to the Zócalo at dawn and climbs a basamento (the correct name for the Mesoamerican “pyramids”) covered in corpses, where he strikes up a conversation with conquistador Hernán Cortés.

And it is in precisely these moments that BARDO resonates the most among the Mexican and Latin American public: when the idiosyncrasy of miscegenation comes to light through the words of Nobel Prize-winning poet Octavio Paz; but also when, in one of the best scenes in Iñárritu’s filmography, magical realism enters — much like in Juan Rulfo’s seminal novel Pedro Páramo — when he covers Silverio’s obsessions with reconciling with his father and forgiving himself for the death of his son. Gama, also like the protagonist in Pedro Páramo, arrives home to a town plagued by ghosts. In BARDO, these figures question his humble upbringing and the hypocrisy of romanticizing a country that seems to exist only as exploitative material for his work.

BARDO, along with Biutiful and Babel, consecrate an unofficial trilogy that explores Iñárritu’s existential anxieties about migration, family, and death. Although the gaze revolves around Silverio, doubts and feelings go from being personal obsessions to universal dilemmas that cross borders, surnames, and egos.

In an interview for several newspapers during this year’s Guadalajara Film Festival, Cacho talked about working on BARDO: “I would describe it as a fantasy. It is a dream to me because I have never worked like that before, and I think I would never be able to do it again with such an amount of time and resources. We will see Mexico City as never before.” Cacho admits that he approached his first collaboration with Iñárritu with a certain amount of trepidation, but ultimately he says he found the experience to be deeply creatively satisfying — one legend working hand-in-hand with another. “I thought, ¡Ay nanita!,” Cacho told Milenio about the opportunity to join the project. “I consulted the I Ching, which I always do when I am faced with an important question, and something beautiful jumped out at me: Above, the mountain, the thunder, the creative genius; below, the lake and serenity.”