Director Andrew Rossi explores the artist’s intimate life in his docuseries adaptation of The Andy Warhol Diaries.

Of the many things the world needs, one item would seemingly not be on that list: another inside look at the life and work of endlessly documented artist Andy Warhol. He is, in some sense, the most known artist in history, the man who made fame and celebrity itself into high art, whose Heinz Tomato Ketchup Box and Marilyn Monroe silkscreens are, at this point, the wallpaper of pop culture, backgrounding all contemporary creativity. Warhol’s genius was in diagnosing and reflecting the obsessions, superficialities, and pathologies of our time. And since Warhol’s death in 1987, the entire universe — for good and for bad — seems to have fallen even further into one of his Campbell’s Soup Cans: reality TV presidents, and the fast-burning fame of social media superstars. He’s been cataloged, probed, and deconstructed in countless exhibitions, books, movies, and even has a dedicated museum in his hometown of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Indeed, with everything as sensationalized as it is these days, sometimes it feels like we could use less Warhol in the water supply — not more.

And yet documentarian Andrew Rossi steps into the monsoon of Warhol’s influence and achieves something truly remarkable: The Andy Warhol Diaries, a fresh, vulnerable look at the person underneath the infamous white wig. Warhol’s oeuvre is typically unpacked for what it says about modern existence; like his notorious (and pretty accurate) prediction that in the future everyone would be famous for 15 minutes and his deep understanding of the effects of advertising and media on our lives. But Rossi’s six-part documentary series, executive produced by Ryan Murphy, takes a different approach: Who is the man, apart from the myth? “My goal from the beginning was to try to reveal the human side of Andy,” Rossi says. “His struggle for meaning in life, the excavating of his true self, and the reality, the truth, of his experience.”

To uncover Warhol’s real world, Rossi grounds his documentary in the artist’s diaries, which Warhol dictated over 11 years — from 1976 to 5 days before his death in 1987 — to an assistant named Pat Hackett. Almost every day, Monday through Friday, Warhol would call Hackett in the morning and tell her about the events of the prior day. She would type it up, and eventually published the full, edited results in 1989, after his death. The project started as a way of keeping financial records — Warhol was frequently audited by the I.R.S. and fussy about money — and he’d note the prices of various purchases. But it quickly evolved into something more personal. Warhol would describe parties he went to and famous friends he saw, offering sly observations and sometimes cutting critiques of the art, fashion, movie, and music worlds he moved in.

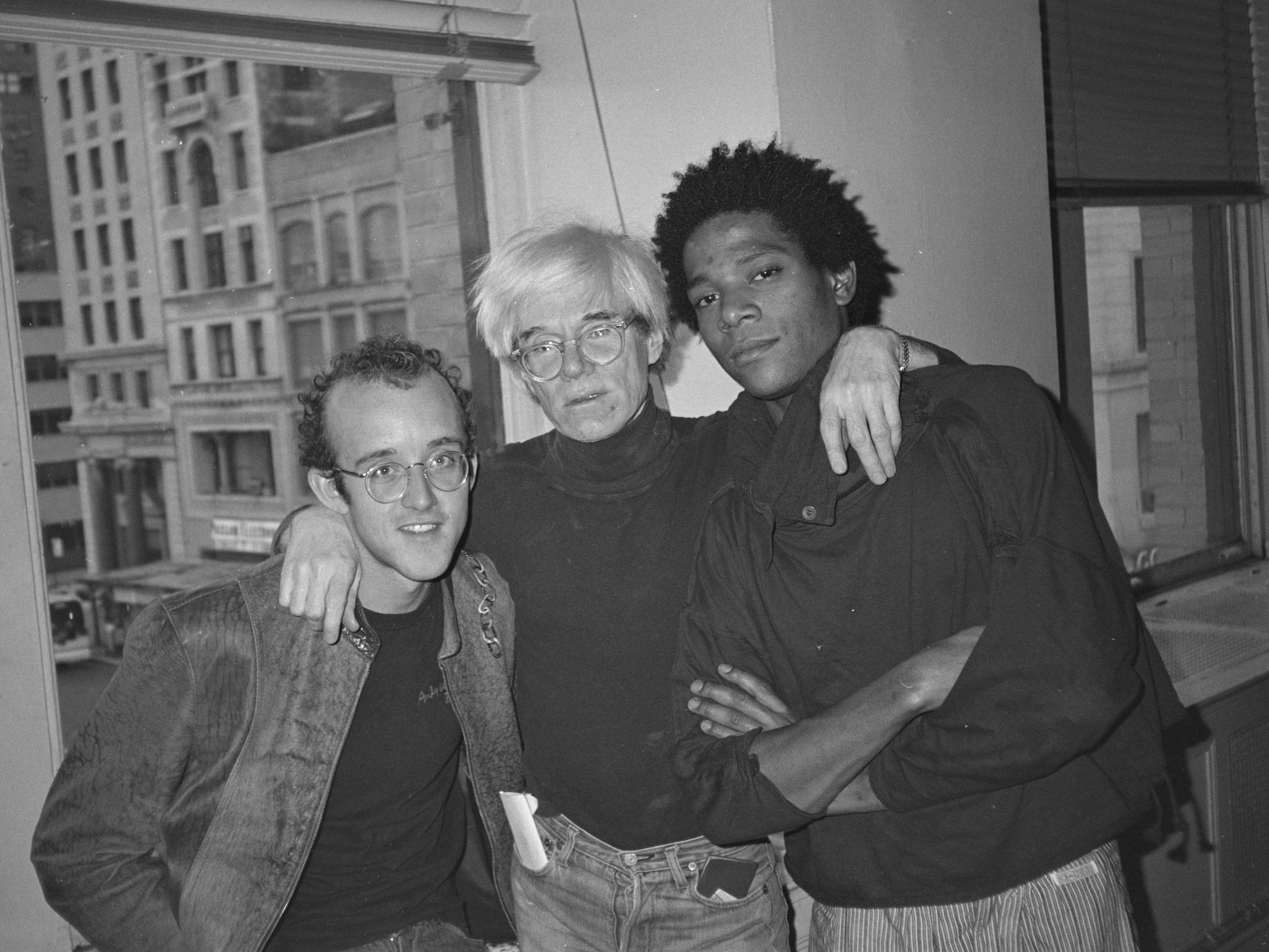

Keith Haring, Andy Warhol, and Jean-Michel Basquiat

While the diaries are notoriously dishy, fun for anyone who loves looking behind the scenes and buzzing about boldface names, Rossi reads between the lines, finding Warhol’s personal life hiding like a palimpsest beneath the artist’s gossip. Warhol was the master of American self-invention. Wig and all, he turned himself into an icon, using his larger-than-life persona, famous friends, and obsession with superficialities to draw attention towards what he wanted you to see, and away from anything vulnerable, including his marked and lifelong insecurities about his appearance and artistic ability. “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface: of my paintings and films, and me, and there I am,” he once said. “There’s nothing behind it.”

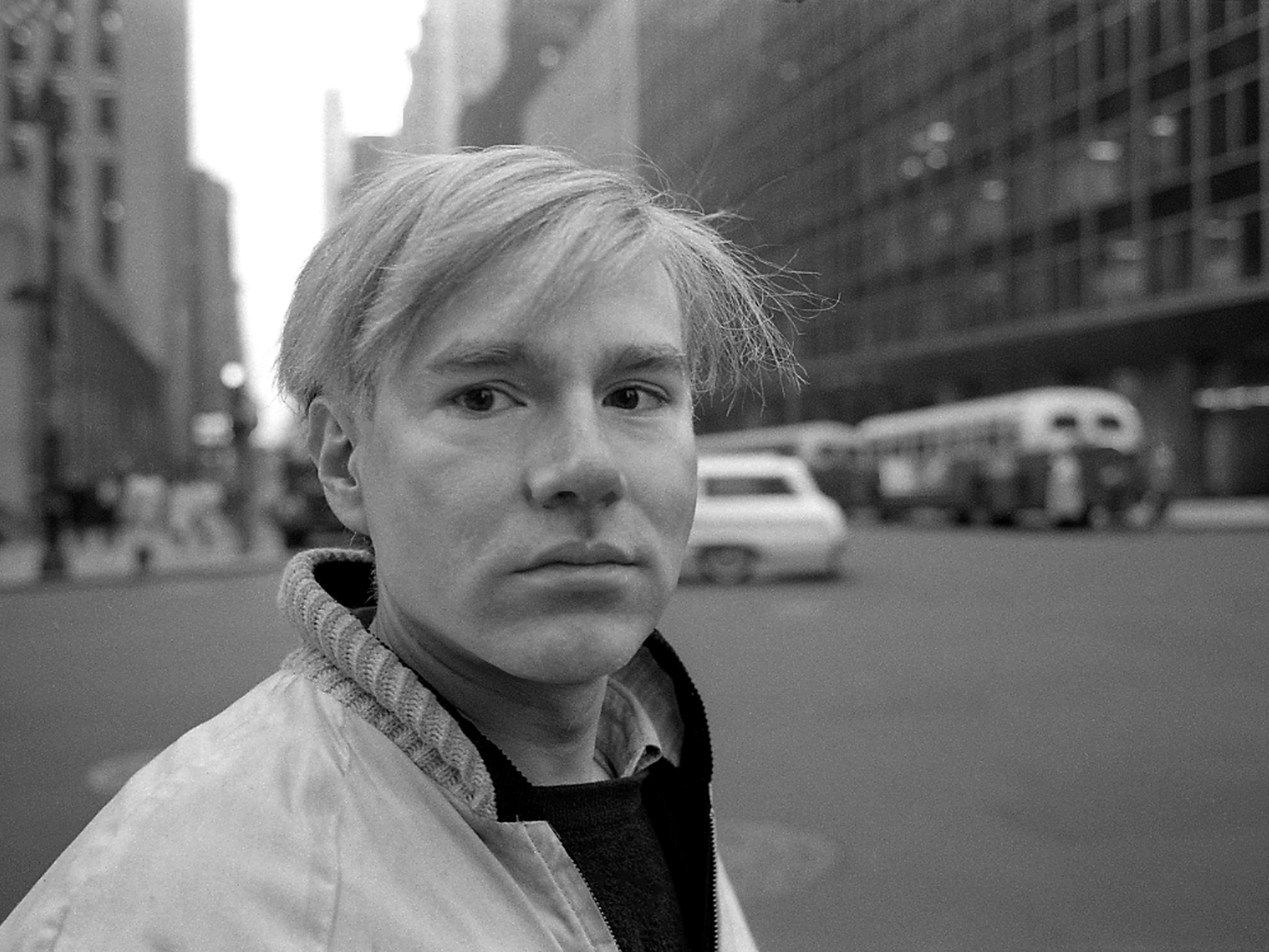

Rossi proves that isn’t true. To do so, he first traces the contours of Warhol’s upbringing by going back to the industrial Pittsburgh of the 1920s and 30s, where Warhol, then Warhola, grew up in a rough-and-tumble neighborhood built around the steel mill industry. “The challenges of trying to find something spectacular or glamorous led him to see beauty and excitement in places that we wouldn’t expect,” Rossi says. Warhol was bullied for being a shy, awkward child, which led to his journey of self-transformation. “He felt that he was unattractive. He struggled with his skin, with his bulbous nose. He went bald very young and he was interested in the promise of reinvention that consumer culture offered through advertising,” Rossi says.

Warhol, who always felt like an outsider, developed an intense interest in what it means to be American. “Andy was first generation, with immigrant parents from Slovenia, and he had this desire to take on the aspirational elements of American life,” says Rossi. “When he took the ‘a’ off of his last name and went from Warhola to Warhol, he became a new character. He always felt that the true Andy needed to be hidden. He needed an armor.” His deep attraction to the idea of the icon also began in Pittsburgh. “His mother Julia took him to the Byzantine Catholic Church every weekend,” Rossi says. “This church has an iconostasis at the altar, which includes images of saints depicted on a very flat surface with gold leaf. They literally sparkled, and Andy saw in the framing of those figures, a model for his silkscreens of Marilyn and Liz [Taylor].”

But where the documentary series really takes off is in New York City, after Warhol became a household name. Instead of focusing on the glittering aspects of that period, Rossi sets out on a path of studying his intimate relationships with three integral men: his two long term boyfriends, interior designer Jed Johnson and film executive Jon Gould, and his friend-cum-protege Jean-Michel Basquiat, the storied New York artist who died of a heroin overdose at 27 years old, shortly after Warhol’s death. “I viewed Jed, John, and Jean-Michel as the men who Andy loved, was sometimes obsessed by, and was in really complex relationships with,” says Rossi, “and also the main figures driving his creative process during those 10 years.”

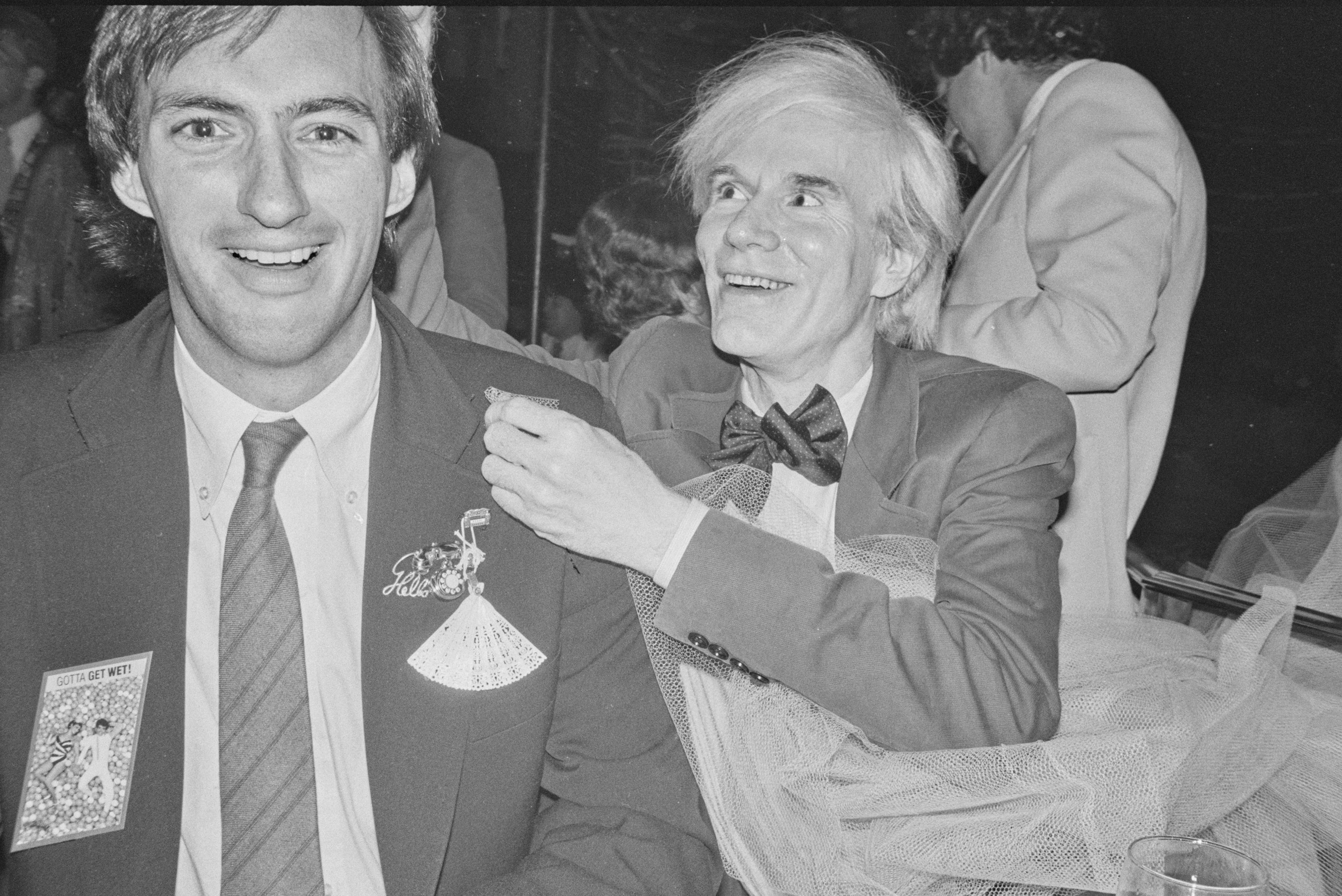

Andy Warhol and friends

Warhol was protective of these relationships — particularly the ones with Johnson, who he was partnered with for 12 years, and Gould, who he was with for 5 — in no small part due to the homophobia of the era. Nonetheless, they were real, long term relationships with massive influence on Warhol’s life and work. The relationship with Basquiat, the Haitian-Puerto Rican artist who is now practically as iconic as Warhol himself, is particularly fascinating: Though there isn’t substantive proof that their bond was romantic or sexual, the two were quite enamored with each other. “Jean-Michel is a figure that gets more ink and attention from Andy in the Diaries than any other, probably, except for Jon Gould,” says Rossi. Their relationship is a complicated one — a tangle of exploitation, power imbalances, racial divides, obsession — and Rossi explores the ins and outs of one of the art world’s most substantive friendships.

Rossi also explicitly frames the series as a queer understanding of the artist, which allows him to view Warhol’s work through that lens. Take Liz and Marilyn Monroe: These paintings are widely understood as a window into the trappings of Hollywood celebrity and modern society, but we almost never ask what those paintings say about Warhol himself. “Andy is identifying with these young actresses and their feeling of not being enough for their audiences, for the culture, their feeling of being overwhelmed by their professional demands, and ultimately their tragic experiences,” says Rossi. “The paintings are the product of a young man’s effort to understand his own position in society as a gay man, who is not reflected in mainstream images, but rather is coded into films. To communicate his experience through narratives that are referring to pain, but not from the first person point of view of a gay man.”

Rossi uses Warhol’s relationship with Gould, his final partner who died of complications from AIDS in 1986, as a prism through which to understand the difficulties of the H.I.V. era. Warhol was characteristically quiet about his grief over Gould’s death in the diary. But Rossi movingly searches for the mourning in a specific series of work, The Last Supper, Warhol’s reimagination of the Leonardo da Vinci masterpiece, which some (including Warhol Museum curator Jessica Beck, who is interviewed for the series) see as an elegy. With Warhol’s passing in 1987 soon after the completion of the painting, it’s impossible to know for sure what the artist’s intentions were. “I would love to understand Andy’s point of view on the Last Supper series,” Rossi says. “Even in an unconscious way, Andy might have been creating some form of post traumatic reflection of Jon’s death. I would be interested to know if he would reject that out of hand or think it was at least interesting.” In finding something unknowable but curious in Warhol’s work, Rossi restores a bit of grace, mystery, and even magic to an artist who’s been endlessly analyzed.

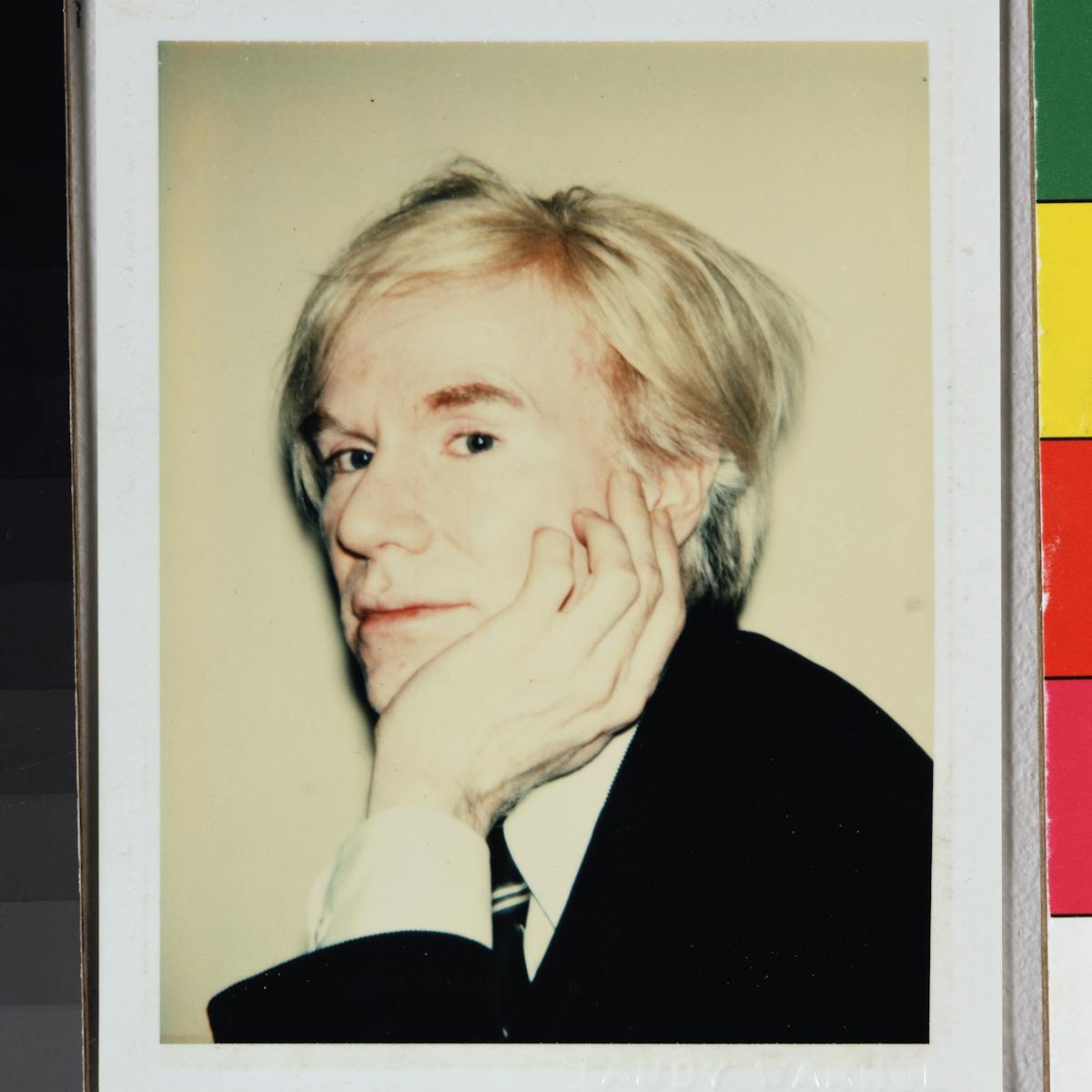

Andy Warhol

Rossi’s rendering of The Andy Warhol Diaries hit particularly close to home for me, an art-loving gay kid who grew up in Pittsburgh, with a passionate longing to move to New York City to make something of myself. I adored Warhol as an adolescent — he represented possibility, excitement, queerness, success, Manhattan itself. I’ve kept a copy of his diaries in my childhood bedroom since high school. But after 15 years of seeing New York up close, my sense of wonder about the city and the culture at large has been hardened a bit, even cynical at times, along with some of my appreciation for Warhol’s work. The Marilyns, which once seemed like glamorous relics, can now feel more like the byproduct of a society overwhelmed by consumerism and addicted to fame. Rossi’s series helped me reconsider Warhol’s art from a more personal point of view, transforming his works from cold observations of pop culture to warmer expressions of personal angst and pathos. The Car Crash works, silkscreens of photos of ghastly accidents, have begun to seem less about an American propensity for sensationalism and violence, and more about Warhol’s marked anxiety around death. His Camouflage series no longer only evokes militarism and consumerism, but his relationship to being in and out of the closet as well. In finding the soul of Warhol, as Rossi helps us do, we can find the soul in his artwork. “I think that Andy was incredibly sensitive,” says Rossi. “It is the great irony that this man who appears as a blank slate is actually covering up a beating heart. I relate to his expressions of disappointment and loneliness and wanting approval in order to assuage the deep feeling of emptiness about the meaning of life.”

The series is constructed beautifully and compellingly across six episodes, with an impressive lineup of talking heads, including friends and collaborators such as John Waters, Debbie Harry, Bob Colacello, and recently deceased art critic Greg Tate. Rossi also uses A.I., remaking Warhol’s voice to narrate diary entries throughout the series. “This is such a pure, raw version of Andy,” Rossi says. “I don’t think I would want an actor to mediate that. You need to feel Andy.”

That’s the ultimate reveal of the docuseries after all — the chance to get to know an artist you thought you already did, to view someone larger than life on a smaller, more intimate scale, to feel closer to paintings that have always been preserved at a cool distance. “I think he’s incredibly relatable,” says Rossi, “when you understand the world through his point of view.”