Andrew Rossi’s documentary features a chorus of collaborators, friends, and admirers of the singular artist.

When The Andy Warhol Diaries was first published in 1989, writer Martin Amis described reading the 800-page tome for The New York Times Book Review: “After a while you start to trust the voice — Andy’s voice, this wavering mumble, this ruined slur.” The same can be said about watching the new limited series documentary, The Andy Warhol Diaries, in which Warhol’s diary entries are narrated by the artist through an A.I. voice program. Watching the archival footage of Andy Warhol with friends, lovers, and boldfaced names that span three decades, the voice establishes trust and then an empathy for this confounding singular fixture of American culture.

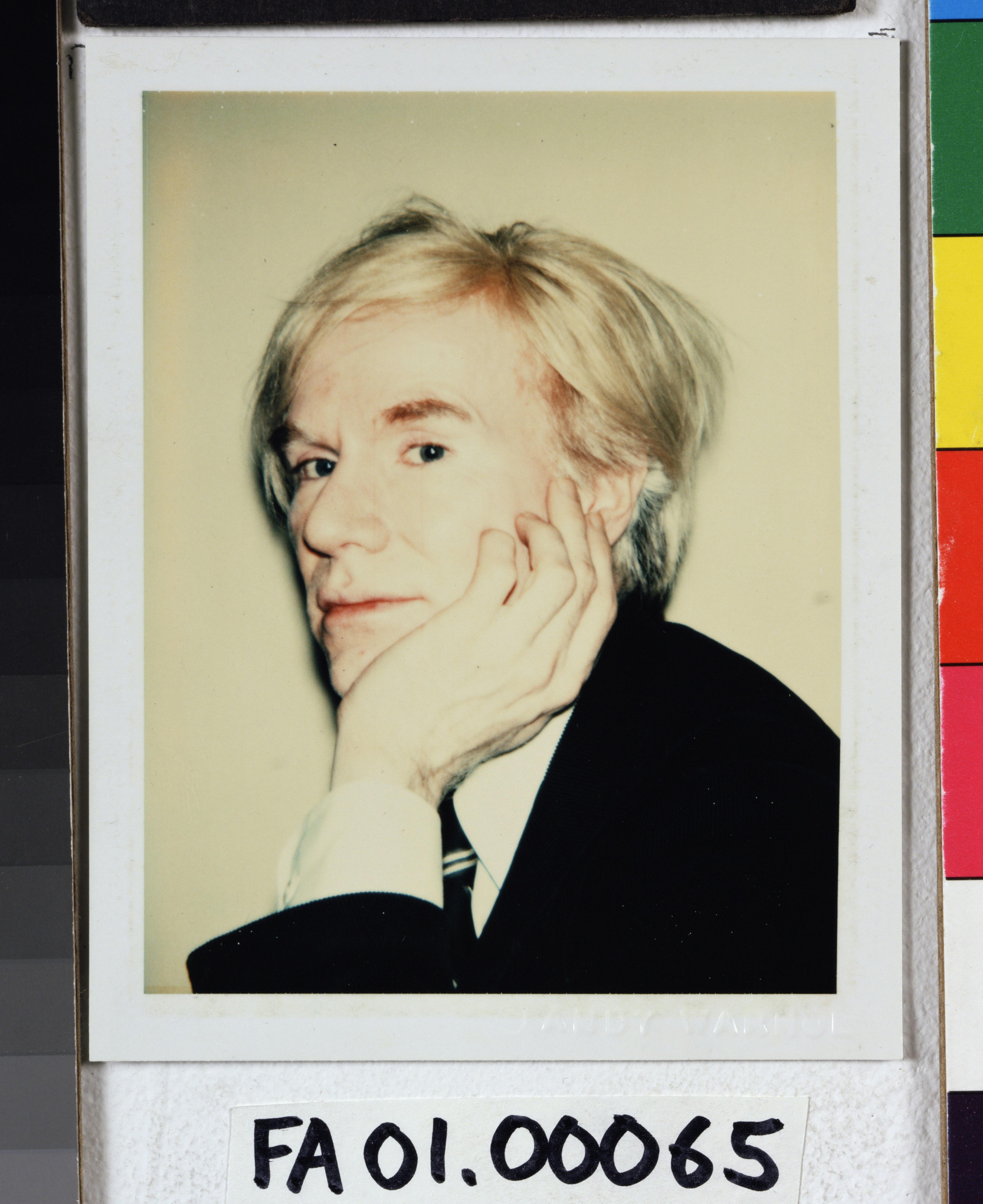

Andy Warhol

Spanning 1976 to Warhol’s death in 1987, the breadth of the diaries is exhaustive; Warhol called his friend-confidante-editor Pat Hackett daily to detail his activities, his physical and emotional status. Pairing diary entries with archival footage and new interviews with those closest to Warhol, the documentary executive-produced by Ryan Murphy is an impeccably annotated journal as much as it is a snapshot of New York City and the world.

“Critics wrote about the diaries when it first came out, and they all said it was so glossy on the surface, but they don’t know how to read it, I think,” explains Warhol’s assistant, Benjamin Liu, one of the voices who sat for interviews with director Andrew Rossi. Warhol, who can be described as ambiguous at best when characterizing both his art and love life, is more exposed here. “This is what he never wanted to show people while he was alive,” says Hackett.

The details of Warhol’s love life, with the impossibly handsome Jed Johnson and impossibly preppy Jon Gould (it’s revealed in the documentary that Gould was featured in the 80s phenomenon The Official Preppy Handbook), are as heartbreaking as his professional missteps. Over the course of one episode (there are six in the series) that parallels the rise of personal computers, Warhol decides to partner with the Commodore 64 as opposed to returning a call from Steve Jobs about his shiny new Apple.

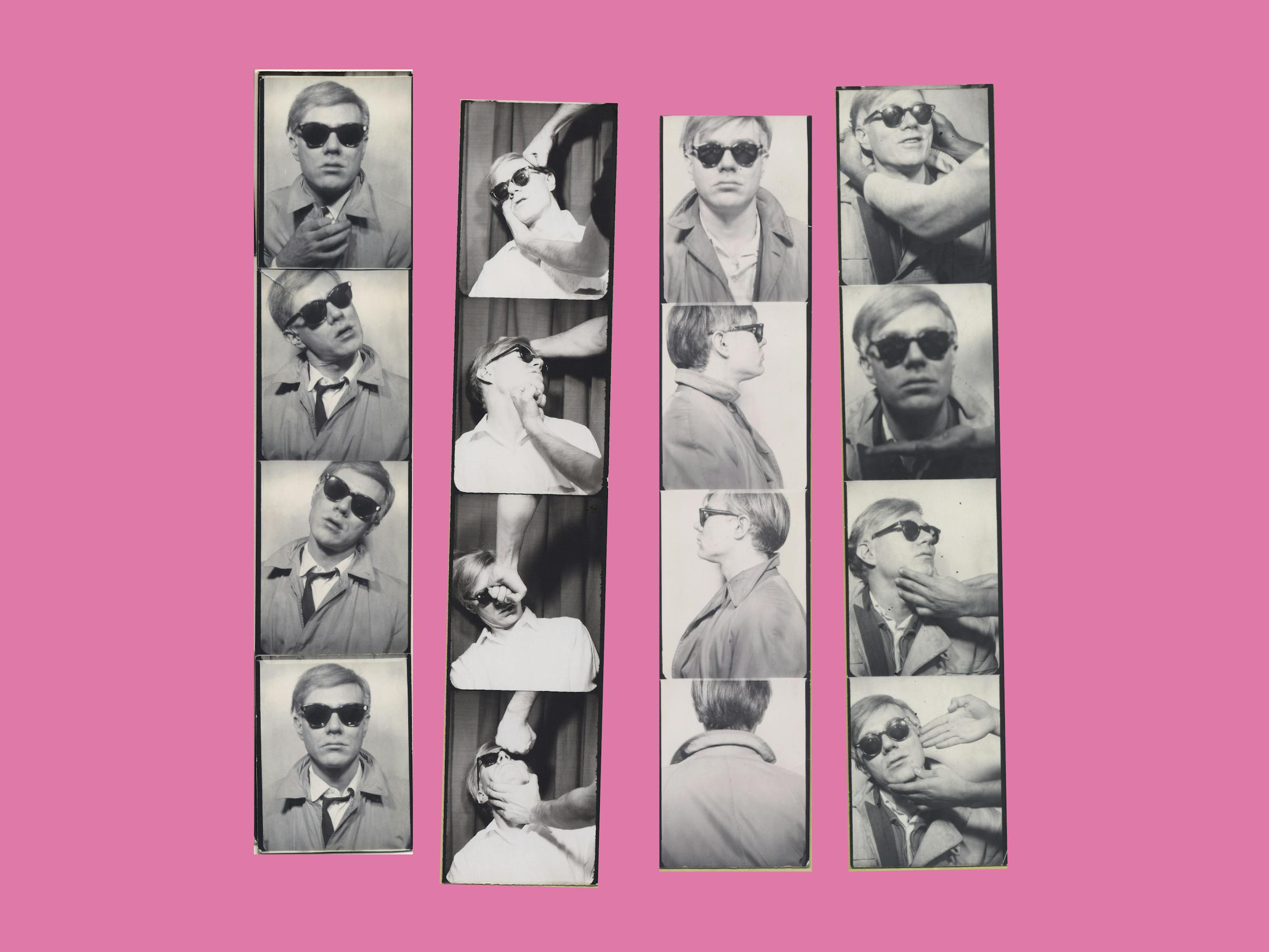

Left: Andy Warhol and Stevie Wonder; Right: Andy Warhol and Jane Forth

While Warhol’s art speaks for itself, friends’, collaborators’, and critics’ voices are also included. Bob Colacello, longtime editor of Warhol’s Interview Magazine is particularly insightful in synthesizing Warhol, the person and the artist. “Andy loved repetition,” referring at once to Warhol’s love for Johnson and Gould, both twins, but also to the most famous motif within his art. “I guess he was essentially a confused person, but he found a way to turn his confusion into art that reflected the greater confusion of America as a country.” One of Warhol’s most fruitful and complicated collaborations was with Jean-Michel Basquiat, to whom he was both competitor and mentor. Jessica Beck, the Milton Fine Curator of Art at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, describes their dynamic: “I think it’s Basquiat who gives Warhol access to a new form of painting, to be more liberal with his personal messaging symbols in the work that speak to personal meaning.” The artists’ collaborations were some of Warhol’s most celebrated works from later in his life.

The most gut-wrenching parts of the story are framed by AIDS. While the whole world struggled to grasp the enormity of the crisis, Warhol’s struggle, filtered through his Catholicism and his own relationship to sexuality, became personal when his partner Jon Gould succumbed to the disease.

Near the end of the series — and his life — Warhol still struggles with identifying and handling his own emotions around Gould’s death. “It’s too hard to care,” Warhol says in one video clip. But he does care. And so do we.