The studio’s founders began animating as preteens. Half a century later, their award-winning creativity continues.

Peter Lord and David Sproxton have spent the better part of the past 50 years goofing around with modeling clay. And while that may not immediately sound like an achievement worthy of celebration, at least on paper, consider this: These two childhood best friends from Woking, England have managed to parlay what began as an odd pre-teen obsession into not only fulfilling careers, but also a singular sort of film-world fame, not to mention four Oscar and 19 BAFTA statuettes. These two men in their late sixties who refuse to grow up are the creative merry pranksters behind one of Britain’s most beloved cultural institutions, Aardman — the stop-motion powerhouse behind the Wallace and Gromit franchise, Shaun the Sheep, and the freedom-fighting fowls of Chicken Run, the 2000 box-office sensation that is about to hatch its first-ever sequel, Chicken Run: Dawn of the Nugget.

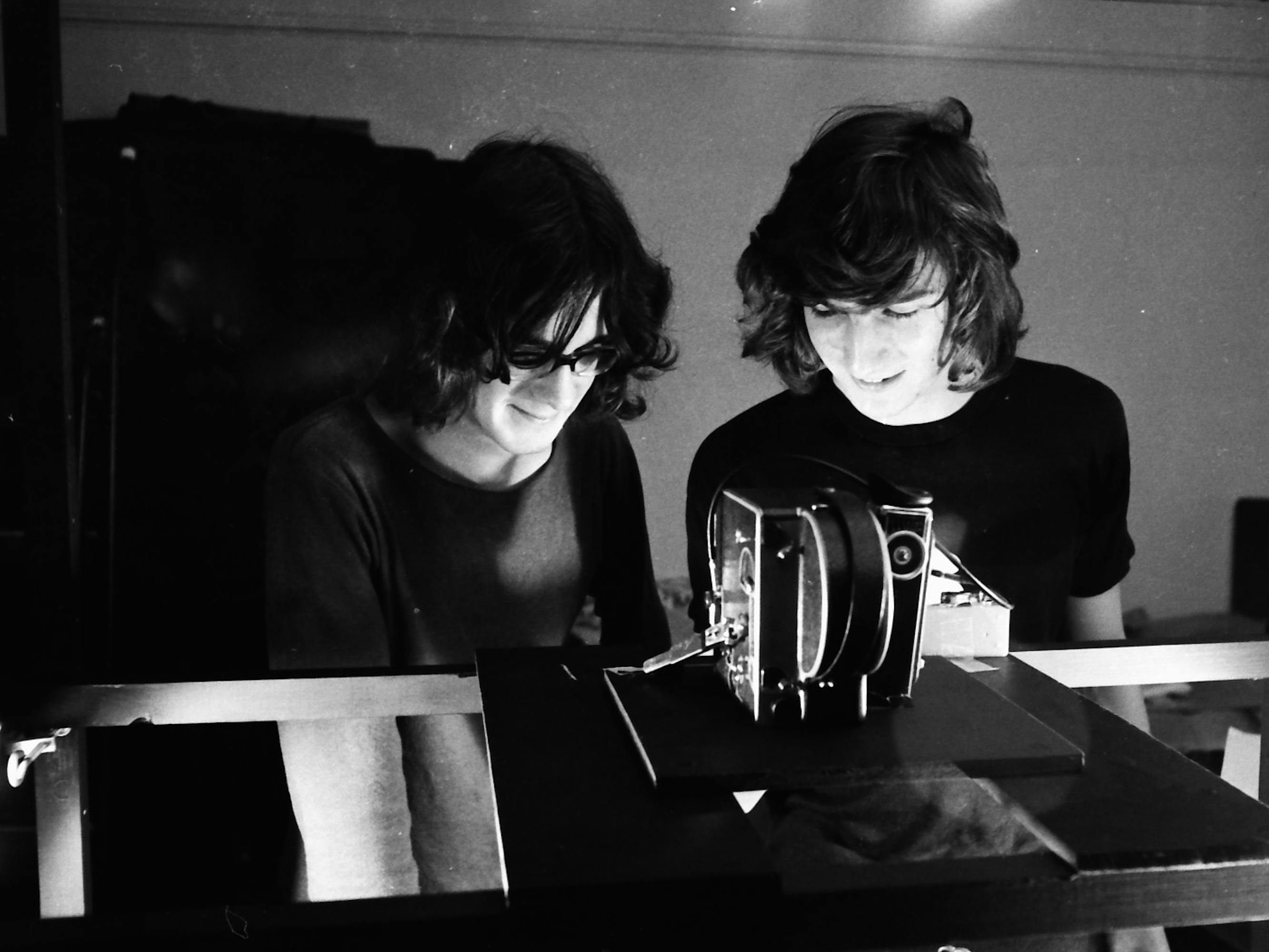

Lord and Sproxton first met at age 13. Lord had just transferred to Sproxton’s grammar school in Woking, Surrey, and as fate would have it, their teacher sat them next to one another. A friendship bordering on a sort of brotherhood was quickly forged thanks to the duo’s shared interests in MAD Magazine, the magical creature creations of Ray Harryhausen, and Terry Gilliam’s surrealist animated bits and bobs from Monty Python’s Flying Circus (another thing the two had in common was that their fathers were both employed by the BBC). On weekends, the boys began to experiment with an old 16-mm Bolex camera that Sproxton’s father stored in a cupboard. Soon, they were using the kitchen table as a miniature shooting stage. After completing their first film using cut-out pictures from newspapers — a short titled Trash — Sproxton’s father introduced the budding young animators to the producer of a BBC show for hearing-impaired kids called Vision On. Thanks to what they half-jokingly call “a bit of nepotism,” they were on their way before they were even old enough to shave.

One of the earliest characters that the self-taught Lord and Sproxton came up with for the BBC was an animated character named Aard Man, an unlikely mascot for what would become an even unlikelier celluloid empire. “He looked like a very low-rent superhero,” says Lord. “He had the old cloak and boots, but he was out of condition and he didn’t do anything remotely heroic or super at all.” Heroic or not, the BBC would ultimately buy the rights to the first film they made featuring Aard Man for 15 or 20 pounds — they can’t remember which. “What amazed me,” says Lord, “is that we were still school boys. I mean, that’s pretty good going.”

Now officially christened “Aardman,” Lord and Sproxton’s shoestring enterprise moved from the kitchen table to a cramped, 500-square-foot studio above an antiques shop on Waterloo Street in Bristol. There, they conjured their next signature character, a Claymation blob called Morph, who could shapeshift into anything their pinwheeling minds dreamed up. Morph would make his debut on BBC One in 1977. Over the next several years, they would begin hiring employees to join Aardman, one of whom would change the trajectory of their little company and nudge it into the big leagues.

Nick Park was a promising film school student at the National Film and Television school in England when he first met Lord and Sproxton. Together, the duo would become a trio — a trio that would reinvent the medium that had fallen on hard times since the death of Walt Disney in the 1960s. Around 1984, the Aardman duo happened to watch six minutes of a student film that Park was toiling on called A Grand Day Out — a Claymation comedy about an eccentric, cheese-loving inventor named Wallace and his faithful beagle, Gromit. It reminded them of the early films of Laurel and Hardy and Charlie Chaplin. It had a cheeky, off-kilter wit and an unexpected dose of pathos and humanity. They offered to help Park finish his film at Aardman.

It was the spring of 1986 and Lord and Sproxton were about to receive an out-of-the-blue phone call that would change their lives. During the first half of the decade, Aardman had become inundated with offers to lend their unique visual style and droll sensibility to television commercials. This was the Golden Age of British advertising — a heady period when the 30-second medium would become a hothouse for eye-candy directors with Hollywood dreams such as Adrian Lyne, Alan Parker, and Ridley and Tony Scott. On the other end of that fateful phone call in 1986 was the manager of Peter Gabriel. Unbeknownst to them, the musician was a longtime fan of Aardman and wanted them to produce and animate a video for his new single, “Sledgehammer,” which was directed by Stephen R. Johnson. After six backbreaking days of delirious stop-motion wizardry, the Bristol studio delivered what is arguably the most inventive and influential music video from MTV’s heyday. “We had no idea it would be such a success,” says Sproxton.

“Sledgehammer” led to numerous opportunities for the company and its artists at home, though they were also working on inventive projects abroad. Heading to New York, they contributed to another touchstone of 80s pop culture: Pee-Wee’s Playhouse with the late Paul Reubens, an avowed Aardman fan. As fun and creative as all of these freelance assignments were, they kept pulling the studio further and further away from its true ambition: big-screen movies. Park began working on Aardman’s Creature Comforts, an animated short that matched animal characters to real conversations of everyday people. It would end up winning Park and the studio their first Academy Award for Best Animated Short in 1991, ironically enough beating out another Park film, the Wallace and Gromit-starrer A Grand Day Out, in the process. Still, the BBC quickly commissioned two more Wallace and Gromit films shortly afterwards.

As the 90s went on, Aardman and the Oscar for animated short film seemed to go hand in hand. In 1994, the Wallace and Gromit short The Wrong Trousers took home the gold, and the googly-eyed inventor and his dog would win again in 1996 for A Close Shave. It was now time for Aardman to dream bigger and segue into the world of feature-length animated films. In 2000, Lord and Park would direct Chicken Run. Clocking in at 84 giddy minutes of henhouse hilarity, it was, hands down, the most ambitious project that Aardman had ever set out on. Recalling his initial pitch to producer Steven Spielberg over dinner, Lord says he needed only 10 words to get the go-ahead: “Steven, we’re going to do The Great Escape with chickens.” That was all Spielberg needed to hear. The 1963 Steve McQueen P.O.W. camp classic was one of the

legendary director’s favorite films. Aardman had their greenlight and a modern classic was born.

An action-packed tale of a heroic hen named Ginger and a slightly ridiculous rooster named Rocky, Chicken Run is a brilliant bait-and-switch of a film. It’s a kid’s film filled with laugh-a-minute punchlines and visual puns, but if you were a ticket-buying parent and you happened to squint just a little, it’s also hard to ignore that Chicken Run is really about a bunch of petrified poultry plotting an escape before they’re slaughtered and sent to the supermarket. The tightrope it walks is a tricky one, and Lord and Park’s film is even more of an achievement for pulling it off so effortlessly. Chicken Run would end up making upwards of $224 million globally at the box office. Immediately, there was talk of a sequel. But that talk would soon fizzle out as Aardman shifted its sights to another Oscar-winning Wallace and Gromit adventure, 2005’s Wallace and Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit. A decade later, with numerous features and other projects in between, the studio’s feature Shaun the Sheep Movie would follow. (In 2022, the franchise’s Christmas special, Shaun the Sheep: The Flight Before Christmas, took home the International Emmy for Kids: Animation.)

Now, just a few short years after signing on with Netflix (which led to the release of 2019’s Oscar- and BAFTA-nominated A Shaun the Sheep Movie: Farmageddon, produced alongside StudioCanal, and the Academy Award-nominated 2021 Christmas short Robin Robin) Ginger and Rocky are finally ready to make their return in Chicken Run: Dawn of the Nugget.

This time around, Ginger and Rocky (voiced by Thandiwe Newton and Zachary Levi) embark on an epic quest to save their adorably mischievous chick Molly (Bella Ramsey) from danger. The chickens are now new parents, with all of the anxiety and excitement that the milestone entails. But, according to Lord, the film was almost grounded before it could take off. In 2005, Aardman’s storage facility was damaged in a fire — and with it, all of the clay models used in the first Chicken Run. “In that fire, all our chickens were roasted. All of the sets, all of the chickens . . . everything was lost.”

Bunty (Imelda Staunton), Mac (Lynn Ferguson), Rocky (Zachary Levi), Molly (Bella Ramsey), Ginger (Thandiwe Newton), Fowler (David Bradley), and Babs (Jane Horrocks) in Chicken Run: Dawn of the Nugget

In other words, some of the biggest stars in Aardman’s stable had to be remodeled from scratch. Lord, for one, wasn’t sure that they would be able to recreate the magic — that it was lost forever. But, he adds, when he finally gazed upon his new flock, he couldn’t believe his eyes. “The first time I saw them resurrected again . . . it was extraordinary, very moving.” As he says this, Lord seems to get choked up. After all, where others may just see clay, he and Sproxton, now with fifty years of experience, have always seen something far more difficult to explain. They see the faces of dear old friends.

All content featured in this piece was captured in accordance with guild guidelines.

All Artwork courtesy of Aardman.