The museum exhibit gives a behind-the-scenes tour of the chart-topping project from auteur Guillermo del Toro.

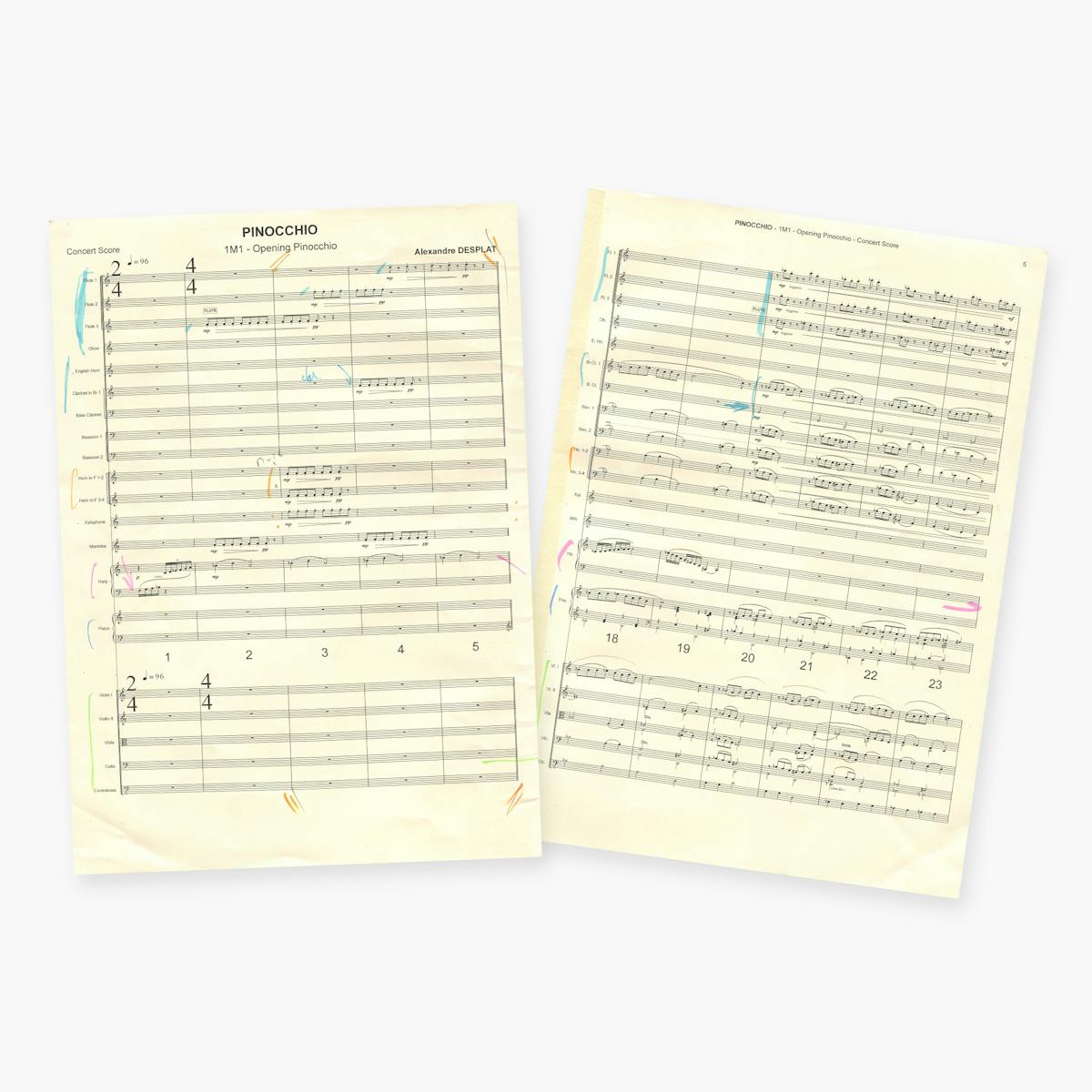

For anyone interested in the artistry of stop-motion animation, walking into Guillermo del Toro: Crafting Pinocchio, the new exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art on view now through April 15, 2023, is a jaw-dropping experience. Dedicated to Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio, the latest film from Oscar winner Guillermo del Toro, the exhibit showcases production art, props, puppets, and working sets from the movie, which sees the writer-director putting his own unique spin on Italian literature’s most famous fairy tale.

Organized in a look development room and a studio room, the sprawling gallery is designed to help visitors understand the rigorous demands of mounting such an ambitious production, one that took years to realize. In each space, time-lapse video installations detail the complex stop-motion process animators used to bring the story’s characters to life. “It’s a privilege and I’m grateful for it,” del Toro told Queue of the MoMA exhibit. “I think of myself as a 10- or 11-year-old coming to an exhibit like this and finding my vocation in animation, my mind exploding with the possibilities of something tactile and human and palpable.”

As much as the exhibition is a tribute to the hundreds of people who spent years designing and animating Pinocchio, it is also a celebration of del Toro’s own boundless creativity, and the profound humanity that lies at the core of all his projects. Touring the show feels like stepping inside the director’s imagination, which is precisely what it feels like to be on one of the filmmaker’s sets. Del Toro transports you to a world where beauty, tragedy, comedy, and horror all co-exist in shades of blue and amber, and a monster usually lurks somewhere nearby. In the center of it all is del Toro, like a mad wizard with his eye on every detail — even those that will likely be imperceptible onscreen.

As a journalist and an author, I’ve written about del Toro’s films for more than a decade, and I’ve been fortunate to go behind the scenes on several of his productions, most recently on Pinocchio, to witness firsthand how relentlessly he pursues his artistic vision. The auteur is as exacting and creative as the films he makes, and collaborators rise to the occasion; the result is always something singular and pure and distinctly del Toro.

That Pinocchio would be the subject of a major exhibit feels more than fitting, not just because of the high level of expert craftsmanship involved in the making of the film, but also because the new movie represents the realization of a lifelong dream for del Toro; this is a story he’s wanted to tell for more than half of his life. It also represents his first foray into feature-length stop-motion animation, an art form that the filmmaker has loved since his childhood days in Guadalajara, Mexico.

By the age of eight, Del Toro had begun shooting his own amateur stop-motion movies using just a Super 8 camera that belonged to his father and his own collection of toys. By the time he was a teenager, the enterprising youngster had begun teaching classes on film and stop-motion animation at his high school. “Back then I thought, Wouldn’t it be great to do Pinocchio in stop-motion?” del Toro remembers. “I thought it would be more like Frankenstein — it would be a horror movie version of Pinocchio about life and death.”

It took decades but his vision for the updated fairy tale eventually began to take shape, with artists at Altrincham, England-based animation studio Mackinnon & Saunders developing early puppets for the film and del Toro bringing on his co-screenwriter Patrick McHale (Over the Garden Wall) and co-director Mark Gustafson (Fantastic Mr. Fox) to round out the dream team. The filmmakers found all-important collaborators, too, in stop-motion animation company ShadowMachine whose co-founders Corey Campodonico and Alexander Bulkley served as producers on Pinocchio and built out a massive Portland, Oregon facility to accommodate the large-scale production.

Standing in the completed exhibit for the first time last week, both Campodonico and Bulkley were overcome with emotion. “We’re flying high right now,” Campodonico told Queue. “The art form that Guillermo’s talking about and the emotion that comes from that — to see it here and to see it at this level of elevation is basically what we’ve been talking about for 10 years on this project. To have MoMA do this is just unreal.”

The idea for the exhibition originated more than a year ago. MoMA curator Ron Magliozzi and curatorial assistant Brittany Shaw flew to visit ShadowMachine’s Portland offices to meet with the filmmakers and see the animators at work on the shooting floor. In time, they chose to fashion the exhibit to highlight in detail the demanding, labor-intensive work that was required of designers, craftspeople, and animation artists working across the U.S., U.K., and Mexico to translate the story from script to screen.

MoMA’s Crafting Pinocchio look development room contains examples of the sample materials — wood, stone, metal, foliage — the behind-the-scenes artists used to test how they might physically create the three-dimensional spaces the puppets would occupy. The area also features reference photos that influenced the design of the film, which unfolds in Benito Mussolini’s Italy, and the “color script” the artists used to develop the movie’s overall visual language. Each major setting in Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio is assigned its own palette: Oranges and greens were prominent in the sequences set at the carnival where Pinocchio becomes a star attraction; cool blues and purples define the underworld of Limbo where the tiny protagonist has several encounters with Death.

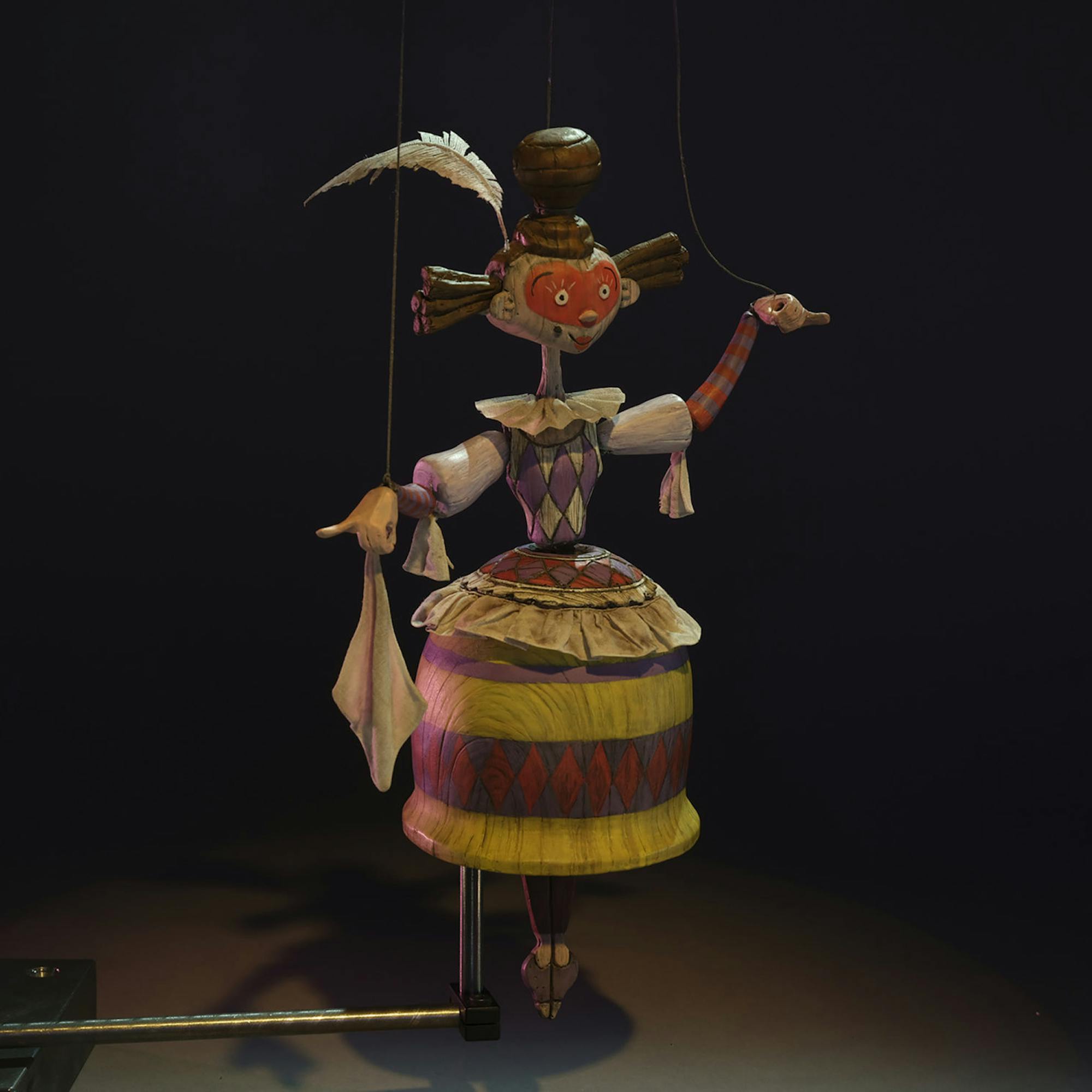

The Death puppet, a stunning, sphinxlike creation developed by the film’s co-production designer Guy Davis, rests in the corner of the look development room with her sister, the Wood Sprite who brings Pinocchio to life, hovering above. Across from them is the enormous dogfish that swallows the film’s heroes before meeting an explosive end.

The Geppetto puppet can be seen in the adjacent studio section of the exhibit, which includes five working sets: the woodcarver’s workshop, the carnival stage, the ocean cliffside, the doctor’s house, and a war games battlefield at the fascist re-education camp where Pinocchio is taught to fight for his country alongside other young boys.

There is also a portion of the village church; the full set stood at 40 by 60 feet and was too large to be included in the exhibit in its entirety, though careful observers will notice characters from del Toro’s earlier films immortalized in the stained-glass windows of the section on display. “Every puppet, every asset was refurbished to the extent that we touched up paint, we removed glue. But Ron, the curator of the exhibit, wanted to keep the authenticity of the production,” notes Bulkley. “This is everything from our studio, just displayed beautifully.”

To ensure that the puppets and the sets would match how they appear onscreen, Pinocchio cinematographer Frank Passingham lit the exhibition according to the movie’s established color script, helping to not only illuminate the space in striking fashion but also to evoke some of the same beautifully bittersweet emotions the film itself elicits. Near the exit of the studio gallery sit the tiny graves that were created for the characters who pass away during the story, with the last line of the movie, uttered by Ewan McGregor’s Sebastian J. Cricket, painted on the wall behind them: “What happens, happens. And then we are gone.”

Notes del Toro, “The movie is about love, forgiveness, how brief our lives are, and how we as a society are constructed of imperfect beings, imperfect fathers, imperfect sons, and we can bypass that. We can love and become real humans.”

Guillermo del Toro: Crafting Pinocchio at New York’s Museum of Modern Art runs from now through April 15, 2023.