When an audience first spies a beloved actor in a truly transformative role, it often can take a beat to move past the sense of familiarity and see only this new character. With Eddie Redmayne, it’s instantaneous. His chameleon-like artistry is evidenced in his Oscar-winning portrayal of physicist Stephen Hawking, who lived with A.L.S. for more than 50 years, in 2014’s The Theory of Everything. A second Oscar nomination followed a year later for The Danish Girl, in which he played Lili Elbe, one of the first transgender women to undergo gender reassignment surgery. Audiences have cheered him on onstage in Cabaret, and he earned both a Tony and an Olivier Award for the play Red, mounted in his native London. Even younger fans have been transfixed by his wizardry, starring as Newt Scamander in the Fantastic Beasts trilogy.

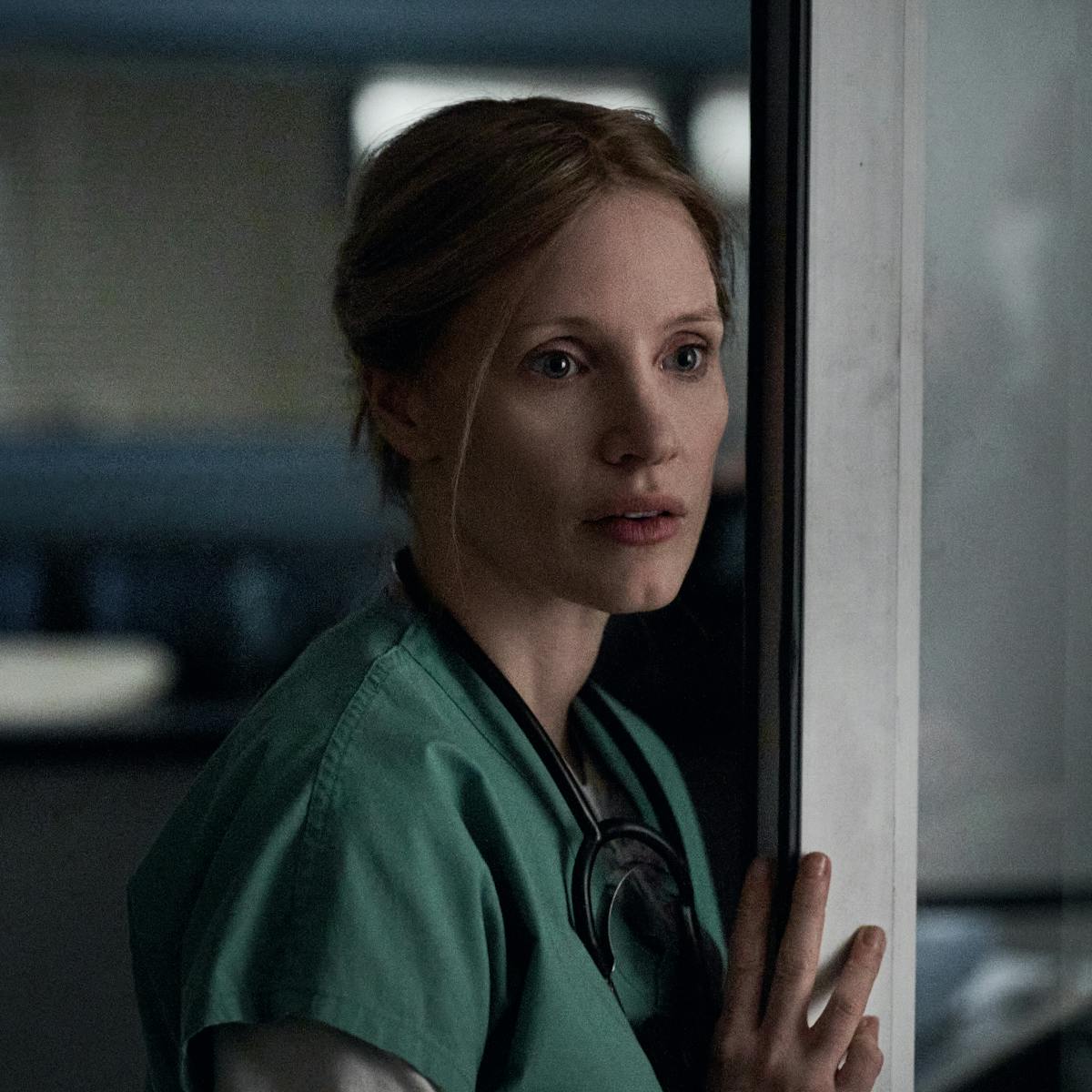

But no role has allowed him to showcase his mastery of metamorphosis more hauntingly than that of convicted murderer Charles “Charlie” Cullen in The Good Nurse, based on the nonfiction book The Good Nurse: A True Story of Medicine, Madness, and Murder by Charles Graeber and directed by Tobias Lindholm (A War). With his apologetic posture and quiet intonation, Redmayne’s Cullen soothes the distressed I.C.U. patients for whom he cares; at their death, he reverently washes their bodies. Cullen’s seeming kindness extends to his coworker Amy Loughren (Jessica Chastain). Learning that Amy suffers from a heart condition, Charlie magnanimously keeps her secret at work and helps the single mother at home. When patients begin mysteriously dying, Amy finds it unfathomable that he could be the cause, let alone a sociopathic serial killer. “Cullen was capable of being such good friends with Amy, while also being the worst beast on earth,” says Lindholm. “There’s no other person who can convey these magnitudes than Eddie.”

Charles Cullen (Eddie Redmayne)

Photograph by JoJo Whilden

To help prepare for the role, Redmayne devoted himself to researching Cullen, who remains incarcerated for his crimes. He spoke with Graeber and Loughren, and, along with Chastain, spent two weeks learning basic nursing skills. Throughout, he tried to reconcile Cullen’s violence with his unassuming demeanor, which helped him get away with an estimated 400 murders. “All I was trying to do was to play this man, at this moment in his life, as truthfully as possible,” he says.

Redmayne’s performance is so powerful it remains difficult for viewers to separate the man from the character long after the movie ends, but Chastain says that he had no such trouble while they were shooting the film. “The second we cut, Eddie was always back to being the most lovely, wonderful, sweet, gorgeous, charming, thoughtful man that he is,” Chastain says. “Then we’d start a scene again and Charlie was back with that creepy voice. He’s brilliant.”

The actor spoke with Edith Bowman on behalf of Queue about the upside of fear, the importance of compassion, and why, if you’re in trouble, he’s the last person to call.

An edited version of the conversation follows.

Charles Cullen (Eddie Redmayne)

Photograph by JoJo Whilden

Edith Bowman: This is the darkest character you’ve tackled. What made you take it on?

Eddie Redmayne: I was at a point in my career when I really wanted to be challenged. There’s a moment when you read a script and you’re enjoying it, and then you project yourself into it and get a sick feeling. That tends to mean I should do it, or try. You’re like, If I’m feeling anxious, that’s probably a good thing. That was the case with The Good Nurse.

You’ve never shied away from playing real people. How did you approach this role?

ER: I’ve found that you have to relieve yourself with the fact that you’re never going to get it “right,” and it’s not a documentary. Charles Graeber, who wrote the book, spent a lot of time with Charlie Cullen, and the book is not only staggering for its information, but also for the way he describes him. I then got to meet Graeber, who went further by giving me some of his notes and other source material.

You also spoke with Amy Loughren, who was initially Charlie’s friend. What were those conversations like?

ER: She was generous enough to talk me through everything about their relationship and what he was like — the way he dressed, what his vanities, his kindnesses, his eccentricities were like. One thing that was really important was to avoid any moment in which the audience could say, “Come on Amy, don’t be stupid,” because she was not stupid. She was formidable, especially when you know the details of how Charlie was able to go about being invisible, blending in and being unthreatening, which allowed him to weave in and out of these institutions and carry out these horrible murders.

Maya Loughren (Devyn McDowell), Charles Cullen (Eddie Redmayne), and Amy Loughren (Jessica Chastain)

Photograph by JoJo Whilden

You and Jessica had two weeks of “nurse” training. How did that go?

ER: It was absolutely hilarious. Jessica was a terrific student — she picked it up right away. I’m totally awful. I’d have to go and practice on my patient dolls for days on end to make working with IV needles look real. For our first scene, I had to inject some stuff — I managed to put the pin through my thumb on the first take. And it transpires I’m a ditherer. I sort of sit there going, Oh yeah, but maybe . . . would that actually work and should I do that? The person’s already dead at that point.

You and Jessica have known each other for years. What was your relationship like on set?

ER: It was a great joy because we approach work in a similar way. We’re a bit obsessive. We like to research as much as we can. But Jess is also just a joy to hang out with — I absolutely adore her. When you’re making a very dark story, you never want it to cloud over your real life. This was one of those great experiences.

Charlie appears so different from how we might imagine a killer. How did you manifest that?

ER: Graeber described Charlie as looking like a question mark. And that was a real insight for me because it was not just his physical posture, but it was a blankness. I worked with Alexandra Reynolds, the movement coach I’ve worked with since The Theory of Everything, and she observed that he almost looked like he was being held up by someone hooking their fingers in the collar of his shirt. His head is always down and cowed, and he’d often look up from that position. I’d practice that at home a lot of the time. I worked with Michael Buster, a dialect coach, on getting Charlie’s voice. And I did lose a bit of weight as well.

Charlie considers Amy a friend, and it is her kindness to him that elicits his confession. How important was it to show his connection to her?

ER: This was a story in which compassion and reminding this man — who was mentally ill — of his humanity prevented him from continuing. The idea of compassion stopping violence was important to all of us in telling the story. And, of course, when you’re playing someone, even if what they’ve done is monstrous, you have to go looking for the humanity. Otherwise, you’re sort of lost, really.