Co-creator and screenwriter Steven Knight on setting the globally devoured book in motion.

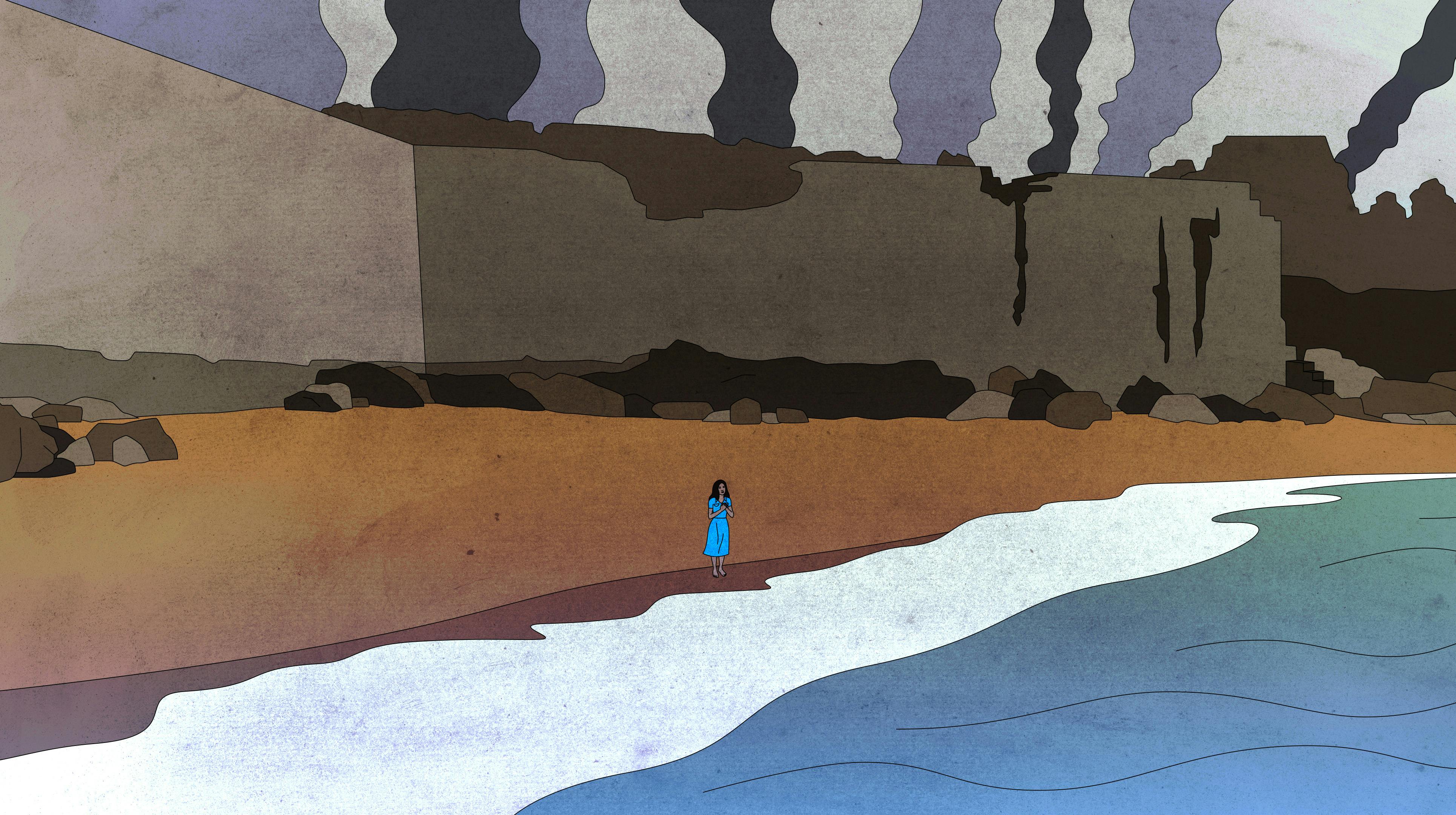

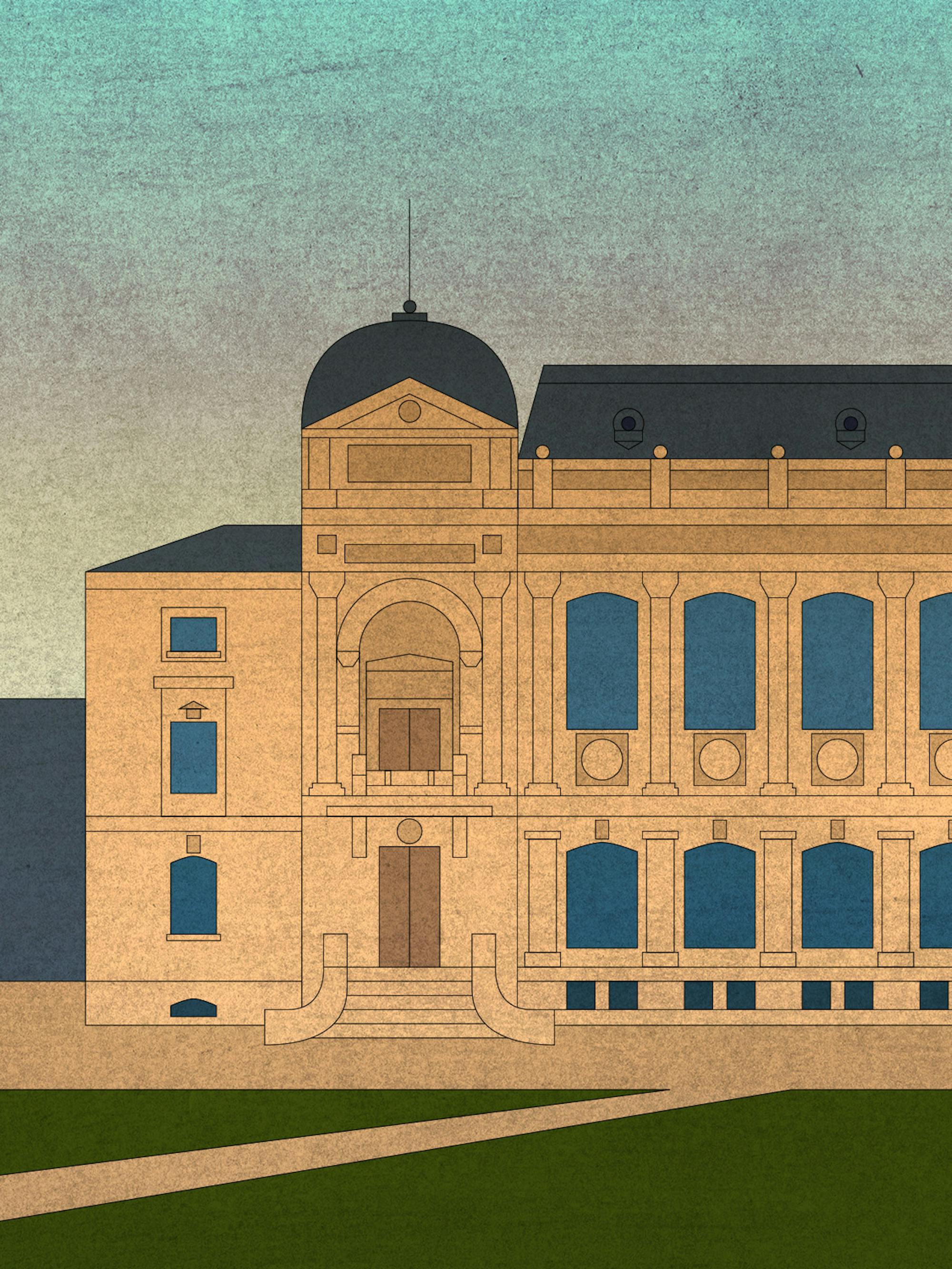

In his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, All the Light We Cannot See, author Anthony Doerr innovates on the subgenre of World War II fiction, bringing to life a thrilling and deeply personal story about the lasting effects of war. When Marie-Laure, a blind teenager with a passion for Jules Verne novels, and her father, Daniel (Mark Ruffalo), the master locksmith at the Museum of Natural History, leave Paris for the country town of Saint-Malo during the Nazi occupation, they carry a coveted (and possibly cursed) blue diamond called the Sea of Flames. Also ending up in Saint-Malo is Werner, a German orphan with a love of science who has been reluctantly drafted to the Nazi cause for his preternatural radio engineering skills. Two strangers on opposite sides of the conflict, Marie-Laure (Aria Mia Loberti) and Werner (Louis Hofmann) begin to intersect in ways that prove life-changing for them both.

Now, screenwriter Steven Knight (Peaky Blinders, See) adapts the beloved novel as a four-part miniseries, directed by Shawn Levy (Stranger Things, Deadpool 3), that does justice to its original material. Here, Knight shares his process for bringing Doerr’s World War II drama to the screen.

The Sea of Flames, a sought-after blue diamond

ON WHAT ATTRACTED HIM TO THE BOOK

The quality of the writing is self-evident, but also when you want to adapt, you have to remember that the writing is not going to be on the screen. The novel was really good because it’s a piece of fiction that acknowledges that, in reality, odd things happen. People are drawn together by something other than just random faith. And with the Sea of Flames, that supernatural element always appeals to me.

ON THE DAUNTING ASPECTS OF ADAPTING

I don’t think it’s worth being afraid of an illustrious author, but when the experience of reading the book is so profound, you then think, What I need to do is attempt to make the experience of watching this equal to that. The beauty of the book is the way that it ends a chapter in 1934, and then it’s 1944, and then it’s 1934 again, and I wanted to keep that fluidity of time in there. But when you’re doing that onscreen, your enemy is confusion. I don’t want people to not know what the hell is going on. Once people understand what you’re doing, going back and forth, then I think they’ll get it.

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas printed in braille

ON RESEARCHING MARIE-LAURE'S CHARACTER

In the adaptation, she’s changing the course of the war by what she does in her bravery. She’s giving messages to the Allied bombers to get the Nazis out of France. Who of us has had that level of agency ever in our lives?

I’m not sure that I was approached [to write All the Light] because I’d done this, but I wrote a series called See. That involved a huge amount of research into the day-to-day life of someone who has one of their senses unavailable. So I did a lot of research then, and [had] some incredible conversations and [built] relationships with people, and that helped enormously.

ON ADAPTING WERNER'S CHARACTER

It’s so heartbreaking, that story. And what’s great about it is that he’s on the wrong side. He’s in the German army, and he’s tracking down resistance people and they’re getting killed. That’s what I love about anything that I’m writing: You want good people doing bad things and bad people doing good things because that’s what life is like. This person, who is just really good at something, is having that pure ability exploited, but he’s still the same person. And all of the heartbreak, his coming from the orphanage — it’s all there. But what I find extraordinary about [Hofmann] is he’s so good at getting that across: He’s saying “Heil Hitler,” and you know that’s not where he is at

Paris’s National Museum of Natural History

ON WHAT HE HOPES VIEWERS TAKE AWAY

I would hope that people who watch this can see themselves in the characters, imagine themselves in extreme situations like this, and ask themselves how they would act. You have a father and a daughter trying to escape from Paris. If you’re a father or a daughter, or you know a father or a daughter, imagine how you would deal with that. If your country is invaded, how do you deal with it? How do you deal with an air raid? How do you deal with all of those things?

A radio and microphone, used to transmit coded stories across Europe and the world

ON THE STORY'S MOST SALIENT THEMES

I mean, God help us, but we keep making the same mistakes. We keep doing the same stupid things over and over again. And we don’t learn, or we learn for 20 years and then we forget. I just think that this story is an examination of the madness of the Second World War, which is a consequence of middle-aged men trying to inflict their insanity on the rest of the world.

When I was watching the final cuts of the episodes, there’s a scene where Marie’s saying, “Our generation mustn’t do this,” and it really did get to me and I thought, My kids’ generation, they have just got to not do that again. You’re going to get stupid people saying simplistic things. Don’t fall for it. I can’t think of anything that is more relevant to today than that message.

All content featured in this piece was captured in accordance with guild guidelines.