Noah Baumbach on setting the 80s satire in motion.

Don DeLillo’s White Noise is the whimsical yet cautionary story of college professor Jack Gladney, his wife Babette, and their four children. We meet this idyllic family right before a bizarre industrial accident forces them to evacuate their small Midwestern town and reckon with their longstanding anxieties and fears.

The novel, which took home the National Book Award in 1985, is set in the same year, but the modern-day resonance of a family faced with the end of their picturesque suburban life remains relevant today. Its enduring themes drew writer-director Noah Baumbach (Marriage Story, Frances Ha) to tackle the rigorous adaptation during the pandemic. White Noise, the film, is a bit of a miraculous event itself because the brilliant but ambitious “Great American Novel” was long thought to be challenging to adapt. To bring the story to life, Baumbach reunites with two of his favorite collaborators for White Noise: Adam Driver (Marriage Story, The Meyerowitz Stories, While We’re Young, Frances Ha) in the role of professor Jack Gladney, and Greta Gerwig (Frances Ha, Greenberg, Mistress America), his collaborator and partner, as Jack’s wife Babette. The result is a surreal, at times hilarious, postmodern comedy that serves as a much-needed antidote to and illustration of our bleak times.

For Queue, Baumbach shares his process and experience adapting White Noise.

The conversation has been edited for clarity.

On rediscovering the book before lockdown:

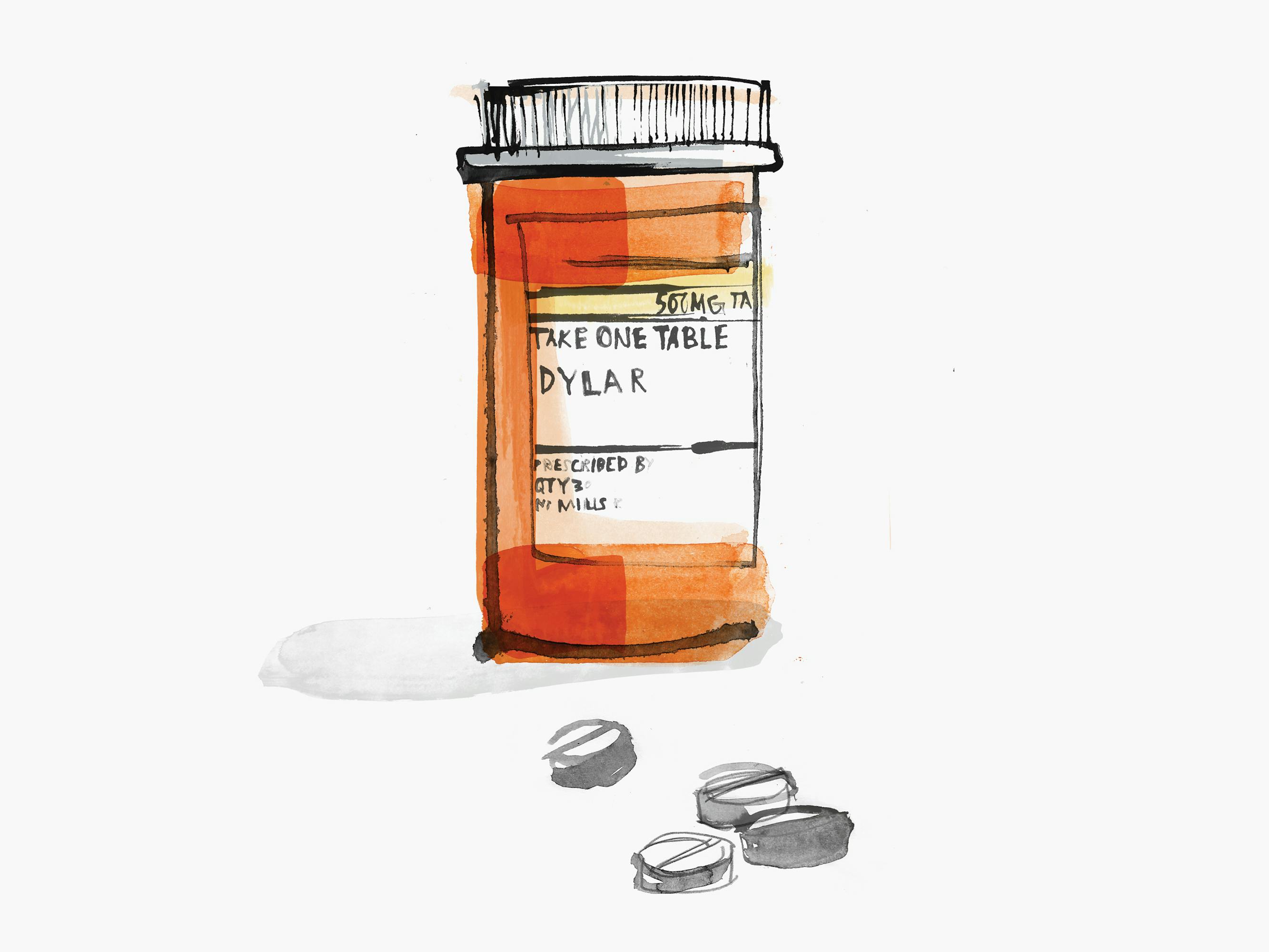

I first read White Noise as a teenager in the late 80s and I picked it up again in early 2020. Clearly images from the book stayed with me over the years: the pill, the man in the motel, and the cloud. As I read passages aloud to Greta [Gerwig], I realized that the novel was timely and expressed a lot of what I was feeling about the modern world. Then the pandemic struck as I finished the book and that added another layer of urgency to its themes. I was curious about whether it could become a movie so I started writing almost as an exercise, and with Greta’s encouragement, there was no turning back.

On translating DeLillo’s language to the screen and tying together the book’s major themes:

DeLillo uses everyday American vernacular and finds an incredibly sophisticated, literary way of telling this story. My job was to find the cinematic analogs to what are essentially very literary ideas. The first part of the movie is about the humdrum of daily life and all the ways we distance ourselves from our own mortality. Part two is about death coming for all of us, in this case, in the form of a toxic cloud that forces the family on a disastrous escape odyssey. Part three can be summarized as what happens after we survive a catastrophe. Can we go back to the supermarket and shop the same way we did before? Can we go about life the same way we did before confronting disaster?

On the movie being funny despite tackling heavy topics:

I view all of my movies as comedies to some degree. It’s just the way I see the world: Moments of levity and moments of seriousness can coexist. This movie is a satire in a way, but it’s also a comedy of manners.

On casting Jack and Babette Gladney:

When I asked Greta who should play Babette, she suggested herself. I always listen to what Greta says. She’s an actor who allows herself to be open and so vulnerable. She is hilarious, so it’s fun to see her do comedic things in the earlier parts of the movie. Adam is someone I always think of when I am writing. This is our fifth movie together and here he has to play someone that is so far from himself. The character is much older than him, and he also had to put on weight and find a new physicality. It was exciting to see this former marine play a pudgy college professor.

On the intricacies of sound design:

The sound in this movie is obviously very important. In any movie, you’ll always have a refrigerator sound or what would be white noise. With this movie, those things are more invisible in the first part, but then they start to get pushed in the later part. Suddenly, things like the sounds of jeans in the dryer, those studs as they hit as they go around, water in the walls, the sound when somebody turns on a faucet — the noises that are described in the book that are often subliminally felt in a movie start to become more featured. Those sounds start to get more freed up in part three as well because of what the cloud has kind of revealed to us. Maybe the viewer wonders, What are they saying in the background? Maybe they catch it, but maybe they don’t and that’s OK.