The lauded photographer brings an honest portrayal of grief to the screen in his short film, starring David Oyelowo.

In just 18 minutes, Misan Harriman’s directorial debut, The After, delivers one of the most honest, gut-wrenching portrayals of grief ever captured on camera. The short film tells the story of Dayo, a London man who witnesses a horrific attack that changes his life and forces him to start a journey of healing and reconnecting. In the role of Dayo, David Oyelowo (Selma, Nightingale) gives a profound and emotionally charged performance.

Harriman, the film’s Nigerian-born director, has reached high status in the photography world for his work in both the editorial sphere, becoming the first Black man to shoot a British Vogue cover in 2020, as well as the advocacy space, documenting protests around the globe. With The After, Harriman uses his keen talent for zeroing in on emotional truths to explore the theme of mental health in moving images for the first time. BAFTA-winning producer Krishnendu Majumdar sits down with Harriman to discuss the journey of The After and the effect it’s left on audiences around the world.

An edited version of the conversation follows.

Misan Harriman and David Oyelow

Krish Majumdar: It is such an astonishing film and it’s your debut. It’s one of the most visceral and eloquent explorations of grief that I’ve seen in cinema. How did this film come about?

Misan Harriman: A combination of timing and a lot of good people wanting to use this medium that you and I love to do the work. I think it’s one thing, me toying with the idea of moving from still image to moving, but I had to meet a series of people who were willing, almost like when I started doing photographs, to take a bit of a calculated risk on giving me a shot. Nicky Bentham, off the back of making the phenomenal film, The Duke, and I were introduced and we just started talking. Her moral compass and sense of intentionality in everything she touches were something I was very attracted to. We then started talking about whether it’s a feature or a short, and it was clear from her guidance and me dipping my toe, if you like, into the moving image, that a short would be the best place to start.

Why did you want to tell stories in this form, in the moving image (as opposed to still images in photography)?

MH: Well, I also describe this film as an act of self-love because cinema was my first love in school, where I wasn’t a very happy little boy. I found joy, I found love, safety, solace, in cinema and VHS and Betamax videos in the earliest of days. I really didn’t think I deserved to have the opportunity to be a storyteller and was kind of programmed to just be happy to be able to consume great art. As I’ve found a sense of stability and love, and thus self-love, in my life, I am now confident enough to try and have a point of view as a filmmaker. My eye, I would say, has been training itself from the very first films I’ve ever seen, which is possibly why as a photographer, and I guess a filmmaker, what I’m putting on the screen seems very intentional and sure-footed; although I’ve picked up the tools late in life, my eye has been training itself from childhood.

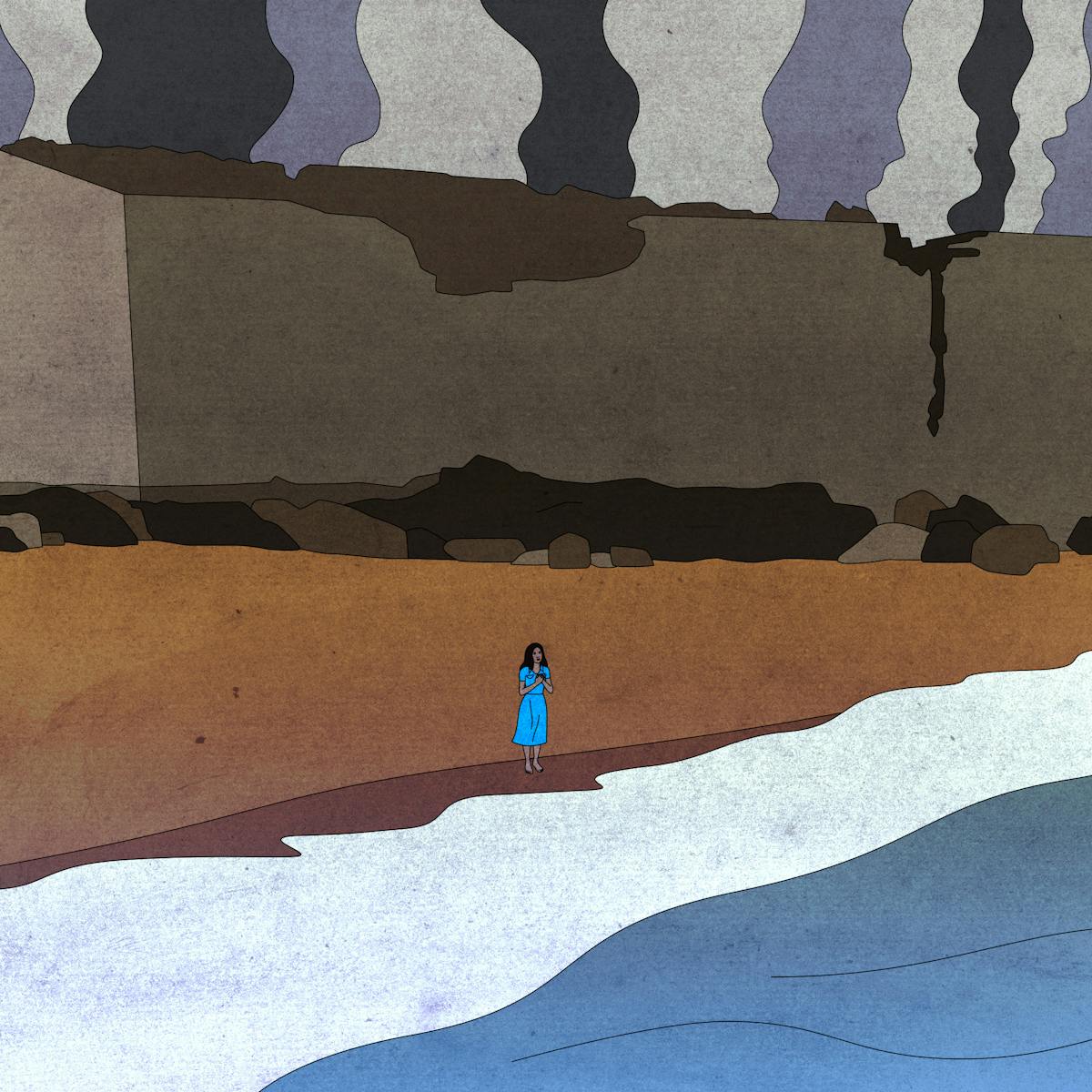

Laura (Amelie Dokubo) and Dayo (David Oyelowo)

Why did you want to tell this story right now?

MH: I want to tell the story right now because I'm not alone in having my own mental health crisis between COVID and George Floyd and so many other things that happened in 2020 — that moment of deep reflection, then coming out of lockdown and all these extraordinary things happening to me, but still knowing that I wasn’t okay. I wanted to help give people some kind of support through art. I believe my pictures have been supportive to many. With film, when you get it right, it can be such an incredibly soft power that reaches into parts of ourselves that bring us so much hurt — places for which we’ve thrown the keys away and don’t even know where the doors are. I wanted to try and make something that at least lets you know that your story matters. It’s okay to have scars both visible and invisible. It is a direct reaction to my own mental health crisis and the need for people to feel safe in building themselves back up brick by brick.

When I get on the train, when I walk into meetings, I look at people’s eyes, and more often than not, when I really look into people’s eyes, I see so much pathos, so much sadness that we are doing everything to tuck away. I’ve been seeing it at a scale that I’ve never seen before. I remember when my wife said the same thing to me. She was like, “Misan, you can’t fool me. I can see the sad boy in your eyes.”

I can be quite sure that we don’t always know what others are going through. We don’t know what demons they have, what hopes, what fears they have. And the only thing that I found that cuts through that in a way that doesn’t seem impersonal and dangerous, frankly, is in music, film, culture, the creative industries. So I guess for a lot of people who know me, it is no surprise that I would have to take it to a place where it’s beyond small talk. I understand that there are light television shows and films — that’s not what I’m going to be as a filmmaker. The After is just a marker of the places I want to take you.

Dayo (David Oyelowo)

So you had this idea, you had this story. How did you meet John Julius [Schwabach], the scriptwriter, and can you tell us a little bit about that creative process?

MH: The story obviously was lingering in my mind, and it needed to be extracted by those who hold the pen. With my level of dyslexia and lack of experience in writing, I knew that that was not going to be me. We were very lucky to be introduced to JJ, and he was just 19 at the time. I love the elasticity of young minds because there are no rules. There are many things that are put on camera and in storyboards, and even in some of the words, that are not always seen in popular cinema. JJ really added beautifully to that. He never second-guessed himself with the ideas that he had, and you can see this on the screen.

The film has such a towering and beautiful central performance from David Oyelowo who is one of our finest actors. How did you attract him to do this film?

MH: I sent him a message letting him know how much I idolize him and that I was thinking of getting into film. He rarely checks his DMs, but he just happened to respond saying that he was a fan of my photography. And the rest, as they say, is history. We are Nigerian-born men, not too dissimilar in age, who have had really similar lived experiences. And that made for magic on every day of shooting because there was so much unsaid that was understood in a glance from him to me or me to him.

There was such an understanding that this was so unusual, having a son of the soil with another son of the soil try and speak truth to the intimate parts of the emotional engines of so many. I think that gave David a sense of safety to do what he did. I really am not even sure I can call what he did acting. I think what he was doing was giving the audience parts of himself that I’m not sure we even deserve. And he left that on the screen. And there were many times when we were rehearsing and shooting where jaws were stapled to the ground due to this man’s extraordinary bravery to allow us to see those parts of himself.

We were doing this waltz, if you like, of trust and creativity that I don’t know if I will ever experience again, but it’s infectious and the rest of the team could feel it and see it, and it rubbed off on all the other actors. It rubbed off on the script supervisor, the first AD, the DOP, all of us.

Dayo (David Oyelowo), Laura (Amelie Dokubo), and Amanda (Jessica Plummer)

What has the reaction been like? What was it like when you watched it with an audience in a cinema?

MH: We had the London premiere at the London Film Festival, and it felt extra special because we shot the film right next door and there was palpable energy in the room. The response has been, frankly, overwhelming. I would also say that current events in the news cycle mean right now people are hurting even more than when we were making this film a year ago, and it’s having that added urgent need for people to find a place, to find some meaning in a world that’s seemingly on fire right now. And this film is doing some of that, helping people on that journey, which to me is the most important endgame, if you putting this out into the wild.

And if you add the fact that now it’s available to 230 million people globally on Netflix, the messages I’ve had from Japan, South Korea, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Ghana, Ireland, and Mexico . . . having people that have completely different lived experiences feel a sense of intimate connection from this piece of storytelling that has been a collaborative effort is my greatest wish.