In Margaret Brown’s documentary, the descendants of the last slave ship to arrive in America contend with their legacy and what lies ahead.

The true depth of documentary storytelling is what is revealed in the process. Whether through investigating, unearthing unspoken narratives, or simply bearing silent witness to what unfolds before the lens, the medium lends itself to the journey of the story rather than its destination. In many ways, all of this rings true for Descendant, the latest documentary feature from director Margaret Brown.

Descendant tells the tale of the legacy of the Clotilda, the last documented slave ship that was smuggled into the United States in 1860, more than 50 years after the slave trade was abolished and made a crime punishable by death. The ship’s journey from Mobile, Alabama to Dahomey (modern-day Benin) on the West Coast of Africa was commissioned by Timothy Meaher, a wealthy local man who drunkenly made the decision on a bet. Meaher enlisted Captain William Foster to chart the course and execute the purchase of 110 slaves. Upon their return to the coast of Mobile, Meaher set the boat on fire to destroy the evidence of the crime. The slaves were ultimately sold and dispersed throughout the South. After emancipation, many of the freed slaves remained near the Magazine and Plateau regions, and ultimately settled and named their city, Africatown.

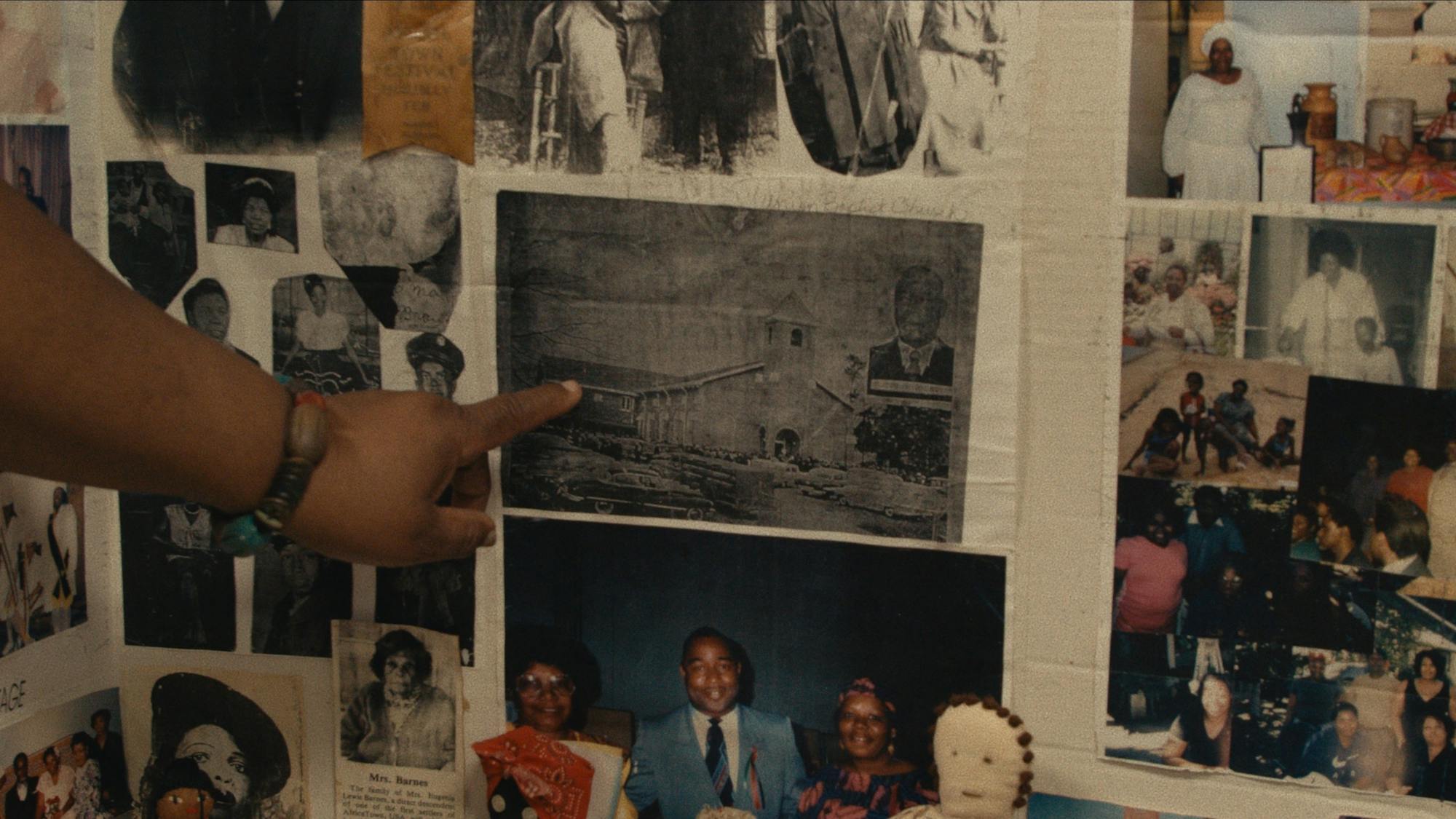

Over the decades, the descendants of the Clotilda remained a close-knit and vibrant community. Through the various descendant organizations and committees of Africatown, the community has passed down their history of surviving the Middle Passage, but kept the narrative somewhat hidden for fear of retribution, and also indifference. “We already knew growing up, but my mom said they were always taught not to talk about it,” says Veda Tunstall, one of the film’s descendant participants. “So it’s like, nobody wants to hear it. Nobody believes it.”

This was the case until May 2019, when word got out that the remnants of a slave shipwreck were found off the coast of the Mobile River. Local and national news outlets quickly picked up the story, swooping in on Africatown and placing the descendant community in the headlines. Over the course of the film, we witness life for the community before and thereafter the discovery of the wreckage. Brown’s camera follows the reckoning that takes place on a host of levels, from the local government’s formal acknowledgment of the crime of the Clotilda, to members of the descendant community meeting with the great-great-great-grandnephew of Captain Foster who navigated the slave ship.

The film weaves together present-day accounts of the descendant community — including participants Veda Tunstall, Joycelyn Davis, and Emmett Lewis — with field recordings and text from acclaimed author and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston, who extensively documented the life of Cudjoe Lewis, one of the longest living survivors of the Atlantic slave trade who arrived on the Clotilda, in her book, Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo.” Brown also taps into the archive of folklorist and scholar Dr. Kern Jackson, whom she previously collaborated with on her 2008 documentary The Order of Myths, and who serves as co-producer and co-writer on Descendant. “Kern did his dissertation on the [descendant] community,” says Brown. “What he brought to the table was just nuts. We would get together and just talk about all the issues kind of swirling around this documentary.”

Diving into reparations, questions of restorative justice, and broader themes of self-determination of the people of Africatown, Descendant carries the torch for the generations who held this story before it. Brown is acutely aware that as a white native of Mobile — although she grew up hearing whispers of Clotilda around town — this was not solely her story to tell. When white residents of Mobile, most notably the Meaher family, declined to participate in the documentary, Brown realized that this project was taking an unexpected course. “When it became clear to me that the white people weren’t talking to me, I was like, “Fuck, I’m going to have so many blind spots,” says Brown. “I cannot do this without a lot of help from the community and producers. Essie [Chambers] and Kern helped me a lot.”

Making Descendant has at once expanded Brown’s acumen as a filmmaker and taught her how to shrink herself in service of the story. “I really feel honored to be let in the conversation because it’s such a traumatic one, and the fact that I was trusted to have a small part of the story feels like a huge honor.” The film has impacted Brown in ways that she’s still figuring out, but mainly it’s taught her how to simply capture what unfurls before her.

Deidre Dyer: How did you approach your previous documentary, The Order of Myths, and how did that film come to shape Descendant?

Margaret Brown: My mom had been the white Mardi Gras Queen in Mobile, Alabama. And I thought I was going to make a narrative out of her story because my mom got disinherited — she married a Jew, my dad, and got kicked out of her family. But then when I went to Mobile and started talking to people about Mardi Gras and I realized Oh, this is a documentary. This is not a narrative.

There’s a whole Black Mardi Gras that’s completely separate, and so I started making this film that was about segregated Mardi Gras. My grandfather was really involved in the mystic societies and he got me entrée into the white society world. There was this sort of whisper campaign about the white queen that year, Helen Meaher. People were like, Oh, everyone knows her family brought the last slave ship. But it wasn’t something I read about in the history books in Alabama.

After Mardi Gras was over, we were interviewing the Black Mardi Gras queen, Stephanie Lucas. And her grandfather, Barry Malone, was like, “Oh, our family came off that ship.” The cinematographer and I just looked at each other like, What? We realized that the two Mardi Gras queens were connected. I’ve never really had a moment like that, probably until the day they found the Clotilda in this film, where I was just like, Oh my God. What the fuck?

Looking at the level of access that you were granted for The Order of Myths, how did that sort of change for Descendant? It’s mentioned in the film that there were attempts to connect with the Meaher family.

MB: It wasn’t just the Meaher family. It was a lot of white families — white Mobile — who were not as willing to talk. Even people that are kind of liberal — they would find ways to, at the last minute, get out of the interview.

While filming — John-Carlo [Monti, additional cinematographer] and I talked a lot about the word reparations — if we should use the word reparations or if we should use the word justice. And [Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture’s Slave Wreck’s Project] Kamau Sadiki, the diver in the film, talks about, What does justice mean to you? If you look at the story of the Clotilda, it’s clear that a crime was committed. We’ve shown it to lots of different audiences in Mobile, and even people who are conservative are like, “Oh, well a crime was committed, therefore there should be a punishment.”

I think people see that something was done that was wrong. These people were brought here against their will, on a bet. And so if you put the word reparations into that, I think it takes on a different [meaning for some people]. But if you just say, “Well, what’s justice in this situation?” then it opens up a different conversation. And I wish the world was a different place where that wasn’t true, where people wouldn’t get all kinds of emotions around the word reparations but I think they do.

I think those who have are afraid of not having — which is not a revelation. In watching the documentary, it’s like, Why do we have to find the ship to know that this happened? Tell me about the day it was found.

MB: I guess we never thought they would find it. When I started [filming] I remember talking to [descendant] Joycelyn Davis and she was just like, I don’t care if they find the ship because it’s about the community. But the day that it happened, all of a sudden, the whole world was interested. Nothing like this had ever been found. And you wonder why? I mean, clearly this is something that no one wants to find because no one wants to look at it. But I think for everyone there that day, when they saw the difference it made, in a tangible way, you could feel the sea change and that was what I wanted to show.

I really wanted the descendant community to be part of the making of this thing in a different way than I’d ever made another movie. My team and I would have daily conversations about, Is this the right way to do this? Am I the right person to tell this story? I asked myself all the time. Even with all my connections to the community and the fact that I’d made films in Mobile before, I still had all those questions.

In a sense, you were a conduit for another community’s story.

MB: Yes, but that was still weird. I’m very proud of the film . . . and I’m glad the story continues. The power of their story is huge.

How do you think this documentary changed you?

MB: I’ve thought about this a lot. It’s hard to say because I think it’s still changing me. It’s so seismic. While I was making it, I just tried to be a really good listener, to bear witness. Because this is a huge story, you have to be in your flow, not frozen with fight or flight. Just listen, watch, and don’t talk too much.

DESCENDANTS IN THEIR OWN WORDS

JOCELYN DAVIS ON WHY IT'S ABOUT THE COMMUNITY AND NOT THE SHIP

Joycelyn Davis

I’m just happy that the world will see this film and know about the story of the Clotilda and Africatown. It’s so much bigger than myself. Growing up we’d always known about the story, but it wasn’t always completely told. Veda and I both attend the church that our ancestors founded, so we are still in the community. Veda’s mom and my aunt would hold festivals to celebrate our ancestors, which would somewhat educate us about the story.

My family [specifically] still lives in the slave quarters that my ancestors founded. It’s an area that has been established since 1870. So every Saturday, my mom would say, “Well, come on, let’s get up. We’re going to the quarters. We’re going grocery shopping for mama,” who is my great-grandmother. My great-grand uncle lived next door to my great-grandmother. It was just common that everybody related was living together within those quarters. So I would go to the quarters every Saturday, not knowing it had been a slave quarters.

I remember when we studied Alabama history in the fourth and ninth grades, there was a little section about Cudjoe Lewis in our Alabama history book. And I was like, Wait a minute, whoa. This story is in our history books. So I’ve always known, but [comprehending] the fully detailed story didn’t come until my adulthood, when I read books like Sylviane Diouf’s Dreams of Africa in Alabama, and Dr. Natalie [Robertson] wrote a book entitled The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Makings of AfricaTown, U.S.A. where it explained the story in full detail. We [had an awareness], but we [only] knew fragments of the story.

People didn’t believe it, but it was all documented. Our ancestors became U.S. citizens. They bought property. And through all of these things, people knew that our ancestors were Africans. Captain Foster kept magnificent notes about how he built the ship and everything. [Timothy] Meaher went through town bragging about what he had done. He went to trial; of course, he was found innocent. After [the verdict], Captain Foster was like, Hey, I went to Benin. I went through the journey. I was there. So to the people who did not believe our story before but believe it now because the ship was found — [I say] it’s always been about the people and not the ship.

People benefited off of our ancestors and the Clotilda brought them over, so I want the community to benefit off of the Clotilda. I want to see economic growth, redevelopment, and all those types of things happen in our community. Whatever [the discovery of the] Clotilda is going to bring, [the descendant community] going to benefit off of her.

VEDA TUNSTALL ON HER DREAMS FOR AFRICATOWN

Veda Tunstall

My mom was in one of the original descendants associations. I grew up attending those meetings with her, trying to help mobilize and locate descendants, even before I really realized what it was. I knew I was a descendant, but it never even occurred to me — a descendant of what? We knew fragments, but we just didn’t have it all put together in a neat little package until adulthood.

Being in this documentary has been amazing. I didn’t expect it. It’s just our life, but now it’s important. It validated the story for the rest of the world. We already knew the truth about it, but when the ship was discovered, all of a sudden everybody was like, Oh, there’s this thing. We’ve been saying it for decades; we’ve known all along.

You know, I think this goes into my skeptical and cynical nature — I never felt the need to prove [the ship’s existence] to anybody. I never cared what anybody else thought. My mom said they were always taught to not talk about it. So it seemed like nobody wanted to hear it. I just never thought much about anybody embracing it.

I believe my mom and everybody else in this community. But now that everybody is embracing it, it just worries me about what people want to do with it. I worry about the political, cultural, and economic impact, all that. I just worry about who all wants a piece, and what they will do to get a piece, and what it means for us. That’s my biggest concern. The ancestors who were enslaved, they were oppressed. It just feels like everything was taken from them, and it feels like that’s still going on.

My dreams for Africatown are more on the practical side. I want to see more people living in Africatown, I want the blight to be addressed, and I want to see upgrades to people’s homes. I want to see vacant property being used to create new homes for descendants and people coming back to Africatown who might have left. I would love to see more businesses in Africatown that are owned by people who look like us. All those things are important. [After watching the documentary], I hope that people are inspired to find their own history and to fight the fight, if it needs to be fought, in their communities, too.