Volume 3 directors break the rules with David Fincher, Tim Miller, and Jennifer Yuh Nelson at the helm.

David Fincher had produced two volumes of his Emmy Award-winning anthology series Love, Death + Robots before he decided to make his animated directing debut in the third volume. His episode, “Bad Travelling,” tells the story of a sailing vessel attacked by a giant, bloodthirsty crustacean. “My take on it skewed more towards [the reality TV series about crab fishermen] Deadliest Catch meets Alien, with a touch of motorcycle touring gear thrown in for good measure. It’s not swashbuckling at all. You get this idea that this is a rough job — it’s not something you aspire to.”

Love, Death + Robots, was a project that Academy Award-nominated Fincher (Mank, Mindhunter) and fellow executive producer Tim Miller (Deadpool) had longed to make for years. Inspired by the boundary-pushing comic magazine Heavy Metal (co-founded by acclaimed comic artist Moebius in the 70s) and motivated by a keen desire to move the needle on animated storytelling, they worked to craft a platform that could house a range of creators and styles under the same roof.

Since its 2019 debut, Love, Death + Robots has impressed an ever-growing fanbase of critics and audiences with its bold, fearless approach. “It’s not even creative freedom,” describes Oscar-winning Spanish animator Alberto Mielgo, “I would say, almost creative anarchy.” Mielgo, whose first season animated short “The Witness” earned two Emmys, returns in the third season with “Jibaro,” a meticulously crafted 3D animation chronicling a deaf knight’s deadly dance with a golden siren. “Jibaro” is the only original work featured in Volume 3.

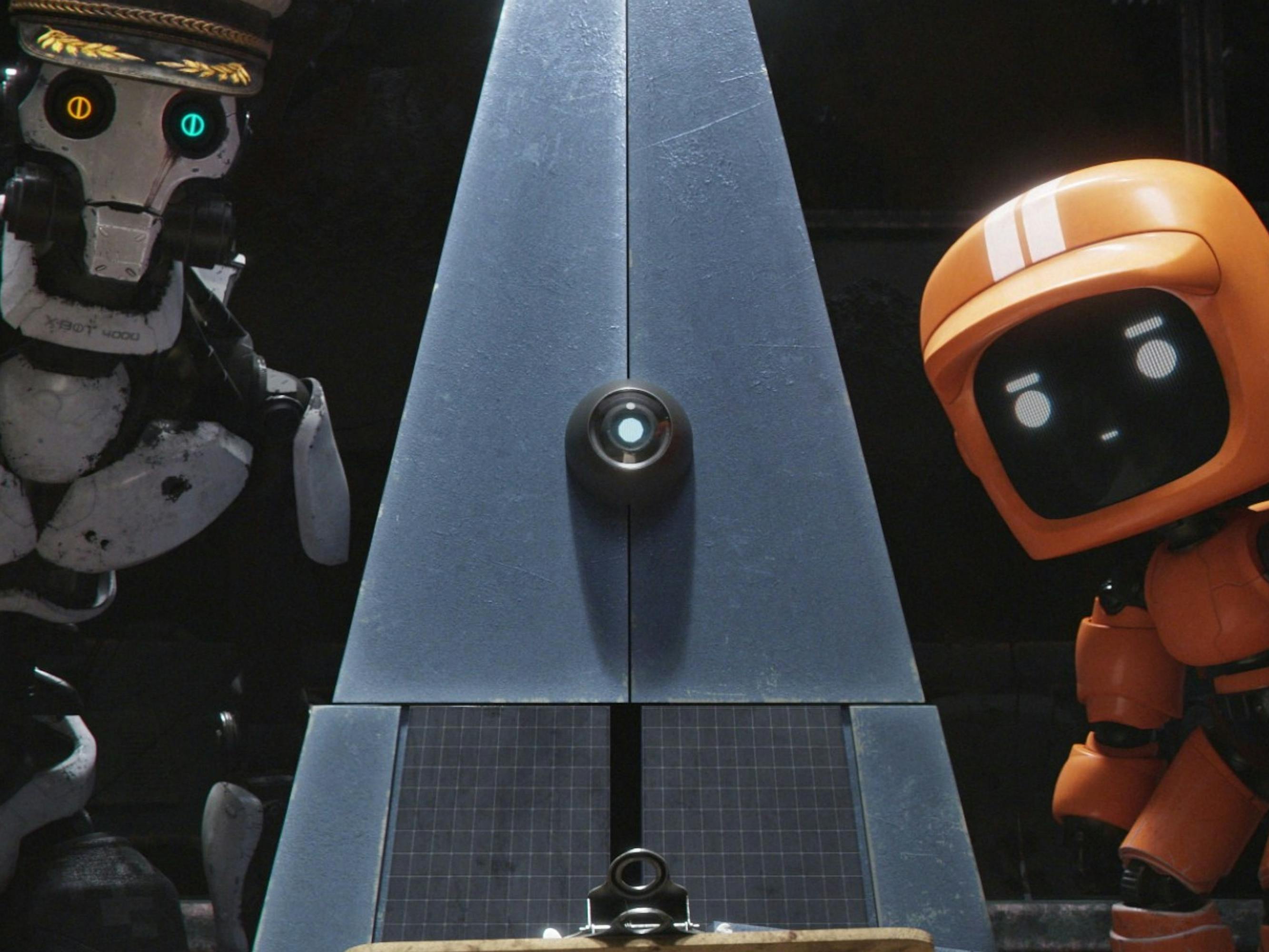

The other eight installments are artful adaptations of sci-fi and fantasy short stories, covering a wide range of animation styles and narratives: Emily Dean’s trippy, Moebius-inflected tale of an astronaut in peril, “The Very Pulse of The Machine;” Jennifer Yuh Nelson’s (Kung Fu Panda 2 & 3) testosterone-fueled, robo-bear action movie send-up, “Kill Team Kill;” and Fincher’s “Bad Travelling” among them. Miller’s entry “Swarm” notably brings sci-fi legend Bruce Sterling’s fiction to the screen for the very first time. Patrick Osborne’s 3D-animated short “Three Robots: Exit Strategies,” meanwhile, is the series’ first sequel, rejoining Volume 1’s “Three Robots” protagonists K-VRC, XBOT 4000, and 11-45-G as they piece together humanity’s final days on Earth.

Queue brought together creators Fincher, Miller, and Nelson (who serves as the anthology’s supervising director) with contributing directors Mielgo, Dean, and Osborne to discuss the anything-goes approach to the series and their wide-ranging inspirations.

Laura Prudom: Love, Death + Robots has served as a launchpad for thought-provoking stories. What were your goals for the third volume in terms of creating continued opportunities for adult-oriented storytelling?

Jennifer Yuh Nelson: For such a long time, everyone I knew in animation kept saying that they wanted to do high-quality animation with challenging stories that could traumatize children — and that’s exactly what the show sets out to do! To be able to talk to directors and say, “You can finally do what you’ve always wanted to,” and to see their faces light up is a huge rush.

Alberto Mielgo: The experience is everything you can imagine. The films are, many of them, pretty weird, and I love that we’re allowed to create something like this in animation.

It shows the flexibility of the medium.

Emily Dean: I’ve always loved sci-fi, fantasy, horror, and genre storytelling. And in animation — particularly in features — it’s difficult to do anything for adults. The industry is dominated by toys, princess stories, and singing animals. Which is fine, but if you want to do something edgier, you have to come at it from a really weird direction. So it was such a thrill to be able to make something that I wanted to see.

Let’s talk a little bit about your inspirations — obviously, we have lauded authors. We have Heavy Metal as a stated influence, which was, of course, founded in part by French artist Jean Giraud, who used the pen name Moebius.

Tim Miller: Moebius is an influence on so many artists in the animation industry. We had definitely felt the lack of a short that paid homage to his style in Volume 1. It had been a goal of ours from the beginning — we had a very Moebius-flavored story idea in the original pitch by writer Lucius Shepard (which I’d still love to do someday).

Dean: I was asked to come in and read some of the short stories they were considering for the next volume. From the bunch, I found [Michael Swanwick’s] “The Very Pulse of The Machine.” I loved how emotionally powerful the story was, but I was also excited by all the opportunities for psychedelic imagery. From that very first meeting, I’d said, “I think this needs to be done in a very graphic, very Moebius-like style. Moebius is a legend, and I felt that a story told in a way that honored the look and feel of his art would be a great addition to the show.”

Mielgo: “Jibaro” was very much influenced by my life. It’s very much about how I see relationships. I have a tendency to go for things regardless of the red [flags]. I’m that person who sometimes chooses partners that don’t treat them all that well. In a way, it’s how I see emotional situations like a toxic relationship that cannot really work at all. I wanted to talk about something very personal and very internal in the form of a sort of fantasy, or fable. Though I generally don’t like fables — not my style at all, too many animals!

Patrick Osborne: From my perspective, it was an awesome opportunity as an animation director to be presented with these existing characters in an interesting world and with a script that’s already working. It was an embarrassment of comedic riches, and the challenge became how to craft it into the best version of itself. It was a directorial game of having fun with a kind of [French filmmaker and actor] Jacques Tati multi-layered composition and staging experiment. It was challenging to think about how I could set-dress the world to have layers of jokes, so if people rewatch it, they can find new layers of visual detail: different T-shirts and posters, and other miscellaneous elements in the sets that continue the fun of [John] Scalzi’s story.

Fincher: I kept telling Jen in our storyboarding sessions that I just want everything to look as miserable as Deadliest Catch. We had this beautiful production artwork that had been done years ago when we were first pitching the show, and it was very [much in the style of British filmmaker] Alexander Korda and The Thief of Baghdad-adjacent. The style was a little daunting and altogether too “fantastic” and I wanted something more gritty. So Deadliest Catch became my go-to.

Nelson: My inspirations were all from stupid 90s action movies when most of the audience and the filmmakers were completely high. It was all about bad lines and guys being stupid in the woods. We had so much fun during the voiceover sessions ad-libbing lines with the actors. Seth Green ad-libbed all these lines for the opening shots where his character is pissing off a cliff. I kept thinking, Wow, I’ve had a really good career and now here I am explaining how to adjust the line read so that the actor pissing off a cliff sounds realistic.

A lot of those movies were all about over-the-top ’roid rage and toxic masculinity pushed to such ridiculous levels itbecame funny.

Miller: The guy that wrote “Kill Team Kill,” Justin Coates, is a really interesting author, as well as an ex-Marine. So he’s got some experience in that particular tone of crazy.

Fincher: When you have to arm wrestle him over a line reading, it’s a serious thing.

Miller: When I come across a story like “Kill Team Kill,” I just think, “Oh fuck. This is awesome,” and I get this little thrill that’s different than when I just read for pleasure. That feeling that you’ve found something that would be exciting to see animated. Take “Bad Travelling” for instance, I couldn’t believe [David] chose that one to make because it had so many strange creatures and horror tropes, I would never have guessed it would be David’s pick.

Fincher: We were able to take most of that out and just make it about Deadliest Catch.

Miller: The interesting challenge with “Bad Travelling” was, How do we stylize characters without making them feel cartoony? I thought we walked that middle path with the designs in a super cool way. All the characters are visually interesting, not even remotely realistic, and completely original. And super greasy, which I love.

David, this was your first experience directing animation.

Fincher: I did motion capture before doing commercials, but I’ve got to say, it was a very reorienting process. It was really interesting to see how all the artists on this [show] think. It’s much more expressionistic. It’s very much one gesture moving into another gesture. Jennifer was helping me inordinately doing storyboards — I haven’t done storyboards in a long time. I used to do them very exactingly, but I found that I don’t want actors to think that I’ve already decided where they’re going to sit. I have already decided where they’re going to sit, but I want to make sure it seems like everybody gets to pitch in. But what was most interesting was how flexible the process is. I can relax my obsession with getting the right master [shot] — just a little — because it doesn’t have to be exactly the way that you see it “in camera.” You can always slide people around virtually later. It’s so much easier than with real humans.

Miller: One funny thing though — because the actors [are] in suits with little balls on them in, essentially, a poorly-lit warehouse, the set is, well, let’s say it’s less than aesthetically pleasing. So David didn’t want to look at the takes on the video playback on the monitor.

Fincher: I can’t see that. It’s like, “Oh great. All these technological harlequins.” It feels ridiculous, all the ping pong balls, and then their weird masks. But how amazing that you can hide the light in the shot? I was like, “We’ve got to avail ourselves of this. We never get to do this [in live-action].” [Legendary cinematographer] Roger Deakins would cut off his left arm to be able to put the light in the fucking shot and not cause a flare or cast a shadow.

Nelson: On the flip side of things, what’s great about having

a more live-action point of view is that it makes everybody on the crew think about the process in new ways. They thought of the shots differently, the lighting differently, the texturing differently, and the set decoration differently — it’s essentially having David Fincher give a masterclass in filmmaking, which was a great experience for the whole crew.