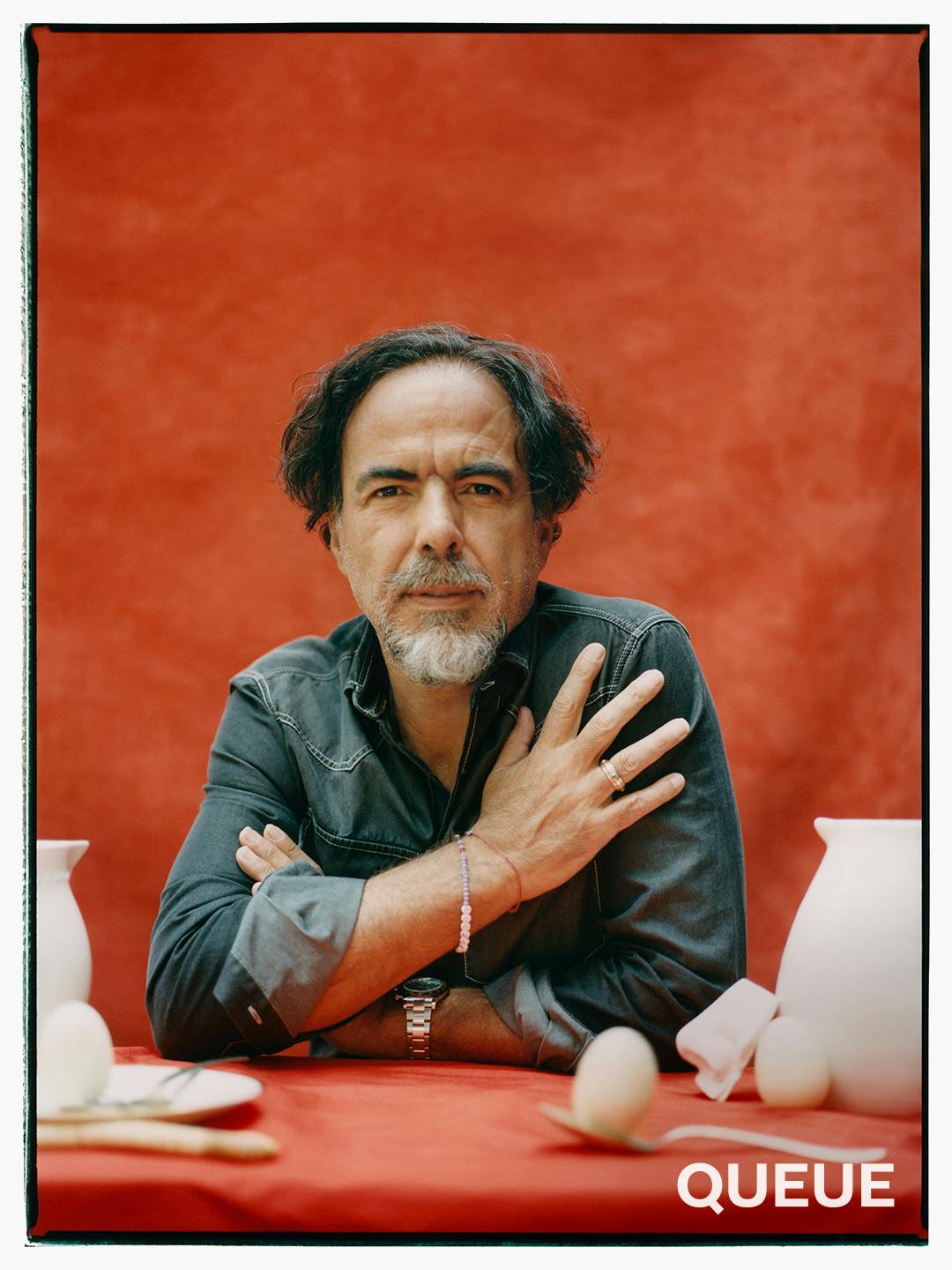

Alejandro González Iñárritu discusses BARDO, his existential return to Mexico.

“Nothing is more boring than the life of a film director,” insists four-time Academy Award winner Alejandro González Iñárritu. “Honestly, we are not very interesting.” Perhaps that’s true — or like many things in the writer-director’s epic existential comedy BARDO, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths, it could be an elaborate fiction that a conflicted hero tells himself while trying to make sense of his own identity, and the larger world.

For his first feature since 2015’s Oscar-winning historical drama The Revenant, the internationally acclaimed filmmaker chose to return to his native Mexico with an astonishingly personal film that reflects many of his preoccupations as a man approaching 60. As it tells the story of renowned Mexican journalist and documentary filmmaker Silverio Gama (Daniel Giménez Cacho) who grapples with his identity, familial relationships, and the folly of his memories, BARDO becomes a visually dazzling, intellectually engaging, one-of-a-kind cinematic experience that’s as challenging as it is rewarding to watch.

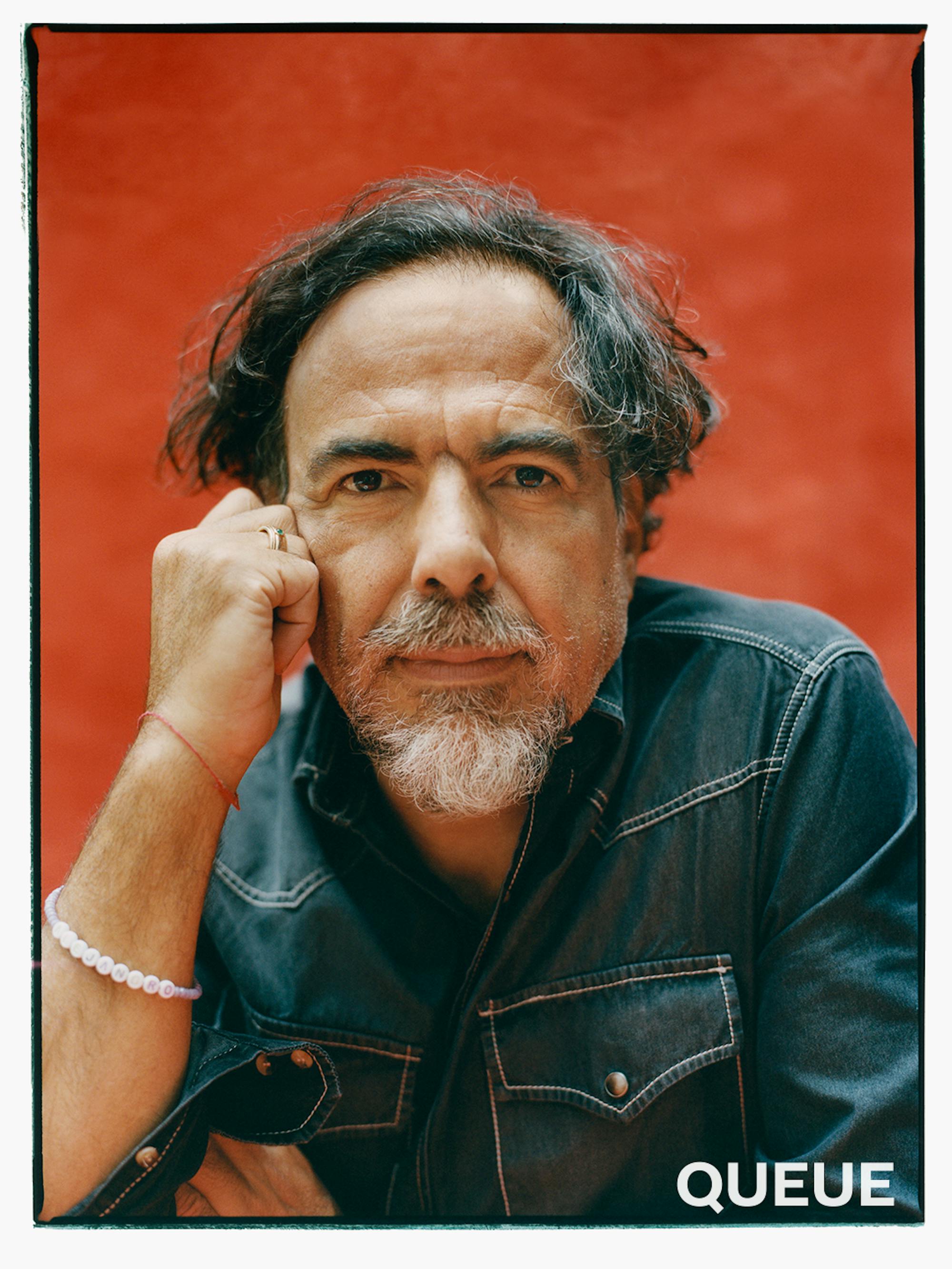

Alejandro González Iñárritu

The film opens with Gama’s shadow adrift in the desert, and there’s no question he’s a man increasingly unmoored from his own life and identity. Although he’s set to receive a prestigious international award for his professional achievements, Silverio can’t manage to fully appreciate the honor, feeling it’s not entirely deserved. Over BARDO’s two and half-hour run time, the scruffy protagonist ponders all the ways in which leaving Mexico for life in Los Angeles has impacted both him and his family — wife Lucía (Griselda Siciliani), daughter Camila (Ximena Lamadrid), and 17-year-old son Lorenzo (Íker Sánchez Solano). Unfolding through a series of surreal vignettes, all shot in luminous 65mm by cinematographer Darius Khondji, BARDO burrows deep into Silverio’s anxieties: How can he be so profoundly shaped by a home that is no longer his home? And do his memories of that place bear any relationship to reality?

Iñárritu recently spoke to Barry Jenkins — a filmmaker whose own intensely personal, Oscar-winning drama Moonlight established him out of the gate in 2016 as a writer-director of the highest order — about his artistic aims with the making of BARDO, the challenges the project posed to his own psyche, and the experience of working in Mexico after almost 22 years away and finding an as-yet-undiscovered country. “It’s hard to get your feelings out there and put your heart out there,” Iñárritu told Jenkins. “It was difficult for me, but as an artist, you have to have courage. That’s our duty. All those fears and all those insecurities I have experienced over the last 20 years — the country where I used to live is not the same anymore, or maybe it never was that way? Maybe it’s just a memory?”

An abridged and edited version of the conversation follows.

Barry Jenkins: Having set out to film BARDO years ago and now releasing it into the world, how do you feel?

Alejandro G. Iñárritu: I wanted to put together a lot of things and to make sense of them. My family and I, 21 years ago, immigrated from Mexico City where I lived for 37 years. We all immigrated for one year, and that year became 21 years in Los Angeles, California. There’s something that happens with time and distance geographically when you arrive to a new place. For me, a home country is no more than the stories that we are told since we are kids that help us to identify with each other, to have a sense of belonging, and to give us collective power. But time, it takes a toll, and those narratives that form a home country start being dissolved. Little by little, that distance starts creating different sensations, and your identity starts to break and to be questioned, internally and by society. You start to be in a place that is hard to define — and that’s valuable. The transformation of some place to the other, that can happen not only in the national identity, it can happen in religious or ideological or political terms, but that elusive space between is a very important thing for me.

After 21 years, all those things start to accumulate, and we build ourselves with some sense of the events that happen in our lives. We think, I’m this, I study this. I felt the need to dive in very deeply and not make a film with the brain, but with my heart, and get inward. It’s very liberating questioning your own story, your own narrative. [Life] events are just experienced from a very narrow, limited nervous system, and sometimes those events are not true anymore because you are challenged by your brother or by your sister, who lived that same event and they say, Things were not like that. My father never said that.

Suddenly, I realized that memory doesn’t have truth; you just have emotional certainty. So the film became a journey about recouping memories, and to do so, you have to reinvent them. It is that journey between reality and imagination. All of this started from there.

Daniel Giménez Cacho

Jenkins: It is interesting that BARDO is still a cinematic construction. I loved watching the film as a filmmaker, trying to unpack how you built this thing because there are so many ideas and the ideas are so fluid, the way you flow through them. The thing you said over and over again was this idea of questioning. I remember when I first began making films, I thought I had to say something. I’m projecting, I’m telling, I’m deciding, I’m declaring, whereas in this case, you’re on this journey of questions, and they’re just funneling deeper and deeper down. When you first began five years ago, what was the foundation, the first blueprint, the scaffolding of how you wanted to tell the story, how you wanted to organize these visions?

Iñárritu: I started with some snippets, I would say, emotional things. I had a recurring dream about my father who passed away in 2014 — I would wake up and he was there. That was maybe one of the first seeds that was planted. Also, my mother is now dealing with some kind of dementia — not being able to grasp her memories for me to reveal my own story, dealing with that. Even a tune that my father used to whistle, that I was very much in love with — I don’t remember that tune and my mother doesn’t remember that tune. So this very little moment for me was so significant, that is implied in the film. Trying to find the little whistle that, in a way, [signifies] all your childhood that is lost.

Another thing is: I’m 59. I’m going to turn 60. I would like to start preparing to die. It’s not that I want to die tomorrow, but this is something that starts appearing a little bit closer when you are older. I want to just go into a lot of things that were trapped in my subconscious.

And I wanted to put them together or make sense of them. And then some historical things enabled me to make sense of the stories of my own country, all the social and political and cultural things that are happening, that I feel so frustrated by, not being able to do anything. All the women that are disappearing — 130,000 people in Mexico disappear with impunity. Those kinds of stories really harm me as a Mexican. When I go there, it’s always this questioning about why I’m here, why I came, what is the toll?

Daniel Giménez Cacho and Ximena Lamadrid

Jenkins: I was completely bowled over by how immersed this film is in your consciousness. It had to come along with all these issues with your father, with your family. Was there ever a moment where you thought, Maybe I will not tell this whole story. I will just tell this piece?

Iñárritu: Not really. In Mexico, we have this soup that is called pozole, with pork and corn and lettuce. It’s full of hundreds of elements. This was my Mexican pozole. The quest and the journey of Silverio, this journalist returning to Mexico before he receives this prestigious award — he’s basically caught between his thoughts. For me, the interesting thing was that we are made of past and present and completely enmeshed in our lives. We sometimes dismiss our dreams. We are dreaming eight hours every day, but we dismiss that part of our lives. But those dreams give us incredibly precise signs [to help us gain understanding] of our own lives. So all that real and surreal and fiction and reality and life and death and future and fears, our memories — all that is very realistic. What Silverio is going through is what I’m going through at this moment.

Everybody’s writing with certainty and truth, but the challenge of life is that it is built by so many fragments of reality — as a journalist, he gets into a middle-aged crisis: Who am I to say the truth? To be humble and suddenly realize that there’s no certainty, it’s scary, but it’s very liberating, for me at least.

Jenkins: This film is described as a comedy. You have a very interesting way of framing your films. Birdman is sort of an existential comedy. The Revenant is very much not. Again, these are all choices. You could have told so many of these stories in very different genre forms or very different dramatic forms. Why a comedy for this story?

Iñárritu: In some other films, I felt that I was diving with the audience into a very dark ocean with all the heaviness of the water on the shoulders and tanks of oxygen. Maybe it’s age that gives you that understanding that even painful moments [have the capacity for humor] — the most intimate relations of Silverio, all the things that have been part of this disintegration, cultural things, all these things that he has on his shoulders, the story of his own country and the story of the country that he lives in now, which is the United States, and the relationship between those countries, all of that formed his subconscious and his being.

Going through this film was a cathartic experience. Some of the most painful memories, I found I was now liberated from them. Once some time passes, you can laugh at them. Suddenly, I was laughing about things that years ago I was really moved by. Now, I can really see them with perspective, and humor gives you a lot of liberation. So with this film, I attempt that tonally. I want this to be a translation, in a cinematic experience, for the audience to be snorkeling. You are not deep in the sea and the dark. You can see the depth, but at the same time, you experience the light and the shades and the grace.

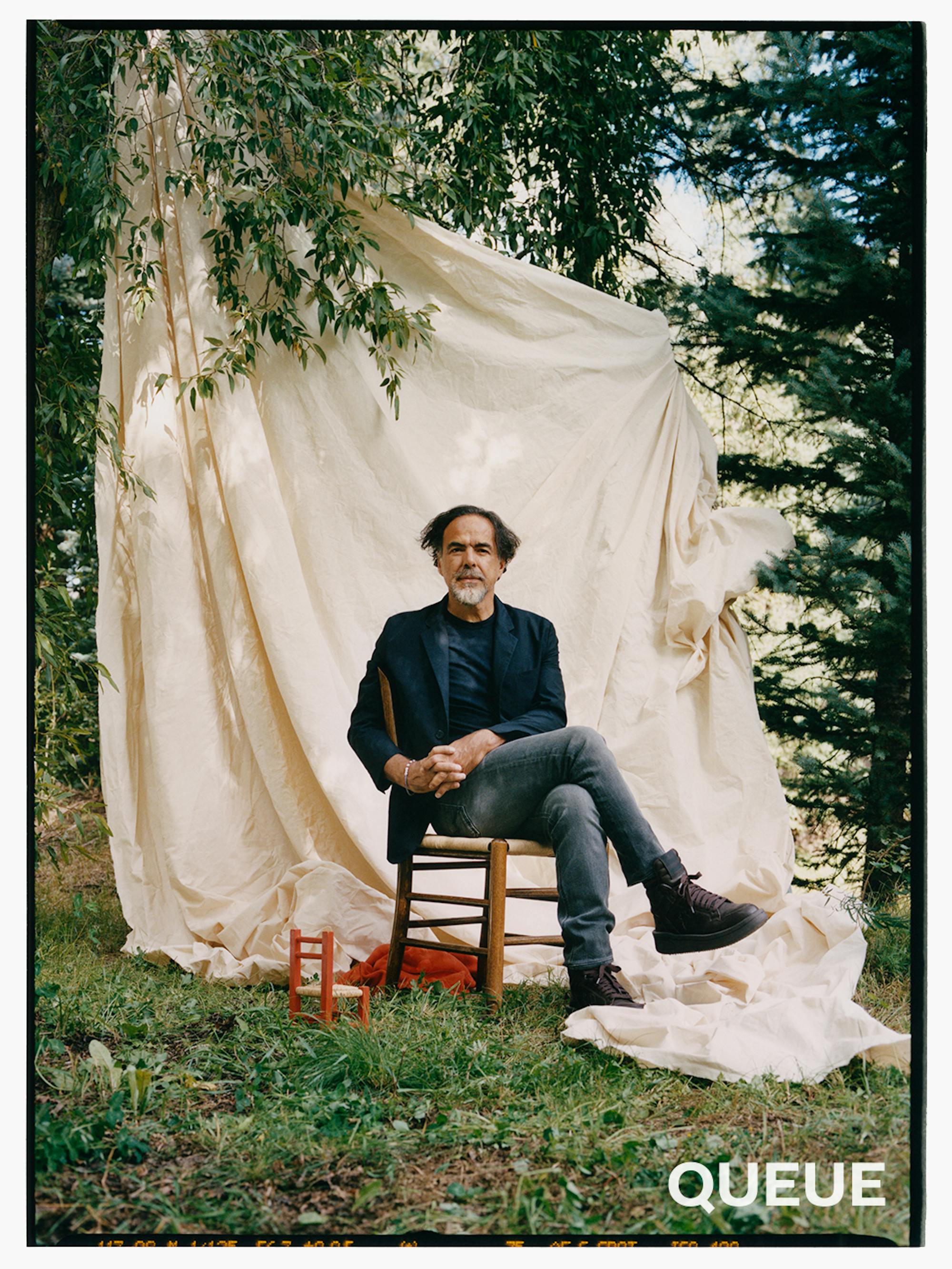

Alejandro González Iñárritu

Jenkins: Amores Perros is the only film other than BARDO that you filmed entirely in Mexico. So it’s a return for you in a certain way. Did making this film teach you new things about yourself or about Mexico? Even hearing you talk right now, its almost like film is therapy. Did watching Daniel Giménez Cacho as Silverio perform all these memories of your life teach you new things about yourself?

Iñárritu: Absolutely. For me, shooting the film in Mexico, after 20 years, became an experience. As I was preparing, we had to stop the film two times because of the pandemic. It was a very challenging film to be doing during the pandemic with thousands of extras with masks. The time that I spent, and the preparation, and all the things that were happening, funnily enough, informed me about what the film was about and really transformed the whole experience personally, psychologically and [from a] directing perspective. It was a meta experience. This film is a dream in a dream in a dream in a dream. It was incredible for me to return there and understand my country and understand what I have lost, what I have gained, and to get even more perspective.

Jenkins: When I made The Underground Railroad, people asked, Who is this show for? I said, “Black people, obviously.” Who is BARDO for?

Iñárritu: I really believe that there’s always an audience for a film. The audiences that will find this film are people who have been feeling uncertain, having some doubts, or who have been through some experiences of suddenly being in this space between. As a Mexican dealing with some Mexican issues and living in the United States, and the contradiction of these two cultures that are so different — yet we are so tight, and our story goes back so far — there are so many things that are not resolved and not talked about or even ignored. For Mexicans, hopefully, this will move them or will reveal the things that were revealed for me. I don’t have answers, unfortunately, just moral certainties. But I think this will speak to every Spanish speaker, or Latin Americans. And I hope that for American audiences who have the curiosity to understand the nature of the other side of the story, BARDO can be a possible bridge to see the other side.