Todd Haynes probes that which makes us uncomfortable in his unnerving triumph, May December, starring longtime collaborator Julianne Moore, Natalie Portman, and Charles Melton.

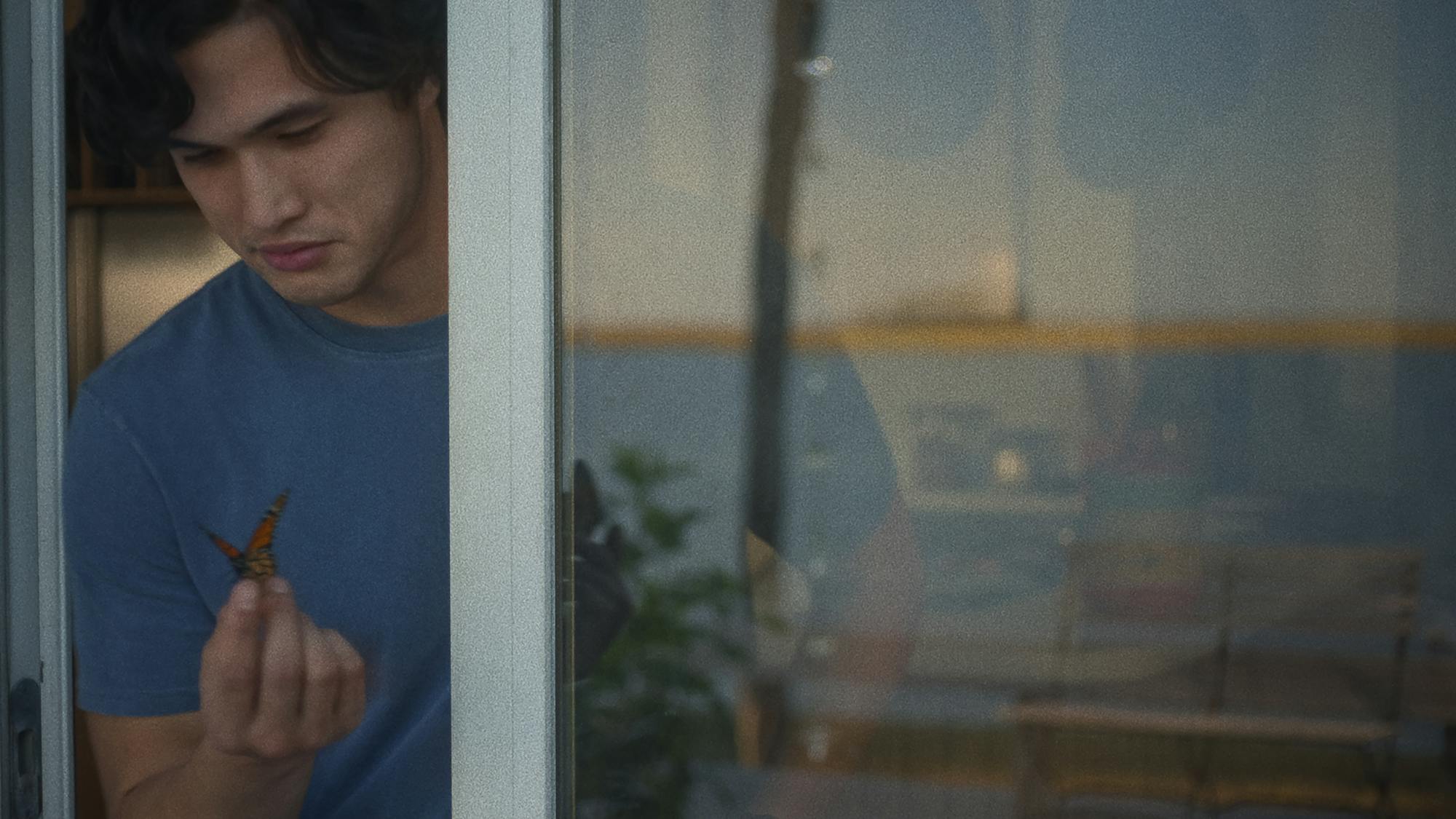

Much of Todd Haynes’s May December, as is consistent across his filmography, unspools at a seemingly idyllic home. Perfumed by the scent of pineapple upside-down cakes, twittering with the sounds of butterflies emerging from their cocoons, and swimming with shadows cast by the buttery light of the film’s Georgian coastal island setting, Haynes’s latest story’s epicenter belongs to Gracie and Joe Atherton-Yoo.

The couple, brought to the screen by Julianne Moore and Charles Melton, are the subject of an independent movie in which TV actor Elizabeth Berry (Natalie Portman) will play Gracie. Elizabeth descends on their Tybee Island home, located outside of Savannah, to study the Atherton-Yoos so as to better portray the illicit beginnings of their relationship — when Gracie was 36 and Joe 13 years old — onscreen. Elizabeth’s mission unearths emotion that has been simmering for decades, and the domestic fairytale that Gracie has constructed soon boils over, blurring the boundaries between actor and subject, performance and reality, denial and truth.

“You think of Elizabeth being this reliable proxy who’s going to chip away at this fortress that has been erected around this relationship,” says Haynes. “I just found, especially today, people bring such a sense of certainty to their opinions and [expect] their identity politics to be confirmed in the movies that they see. The script pushed in all of these places of discomfiture for me.”

After a recent screening at the Crosby Hotel in New York, Hereditary director Ari Aster spoke with Haynes about the films that inspired May December, Melton’s spellbinding breakout performance, and how, according to Aster, Haynes is the filmmaker “alive right now who is the most connected to the aesthetic and language of melodrama.”

An edited version of the conversation follows.

Todd Haynes

Ari Aster: The film puts you in this position where you’re quickly judging the characters. Over the course of the film, those judgments become confused, the film expands, and at the same time, it alienates further and further. There’s a question in there, find it.

Todd Haynes: Everything you’re describing about the film is what I loved about Samy Burch’s script. This script made such an impression and cut through the noise of stuff that was around. I felt what you just described, where you think you know how you feel; you bring certain moral positions to this story.

I thought of Bergman right away. That monologue Elizabeth [delivers] toward the end of the film, I just immediately thought of Winter Light with Ingrid Thulin. The mirror scenes, the static camera, and the removal of the sight distance that we occupy from the subject matter were all things that fell into place. And then The Go-Between from 1971.

AA: You have a 13-year-old boy in that film as well, who’s losing his innocence. That’s a film that was written by Harold Pinter, and I really see a lot of Pinter in this, in the way that the character dynamics don’t only shift but they contort.

TH: Samy, are you hearing this? That’s saying a lot because what’s not said, the subtext and the silences, by Harold Pinter in his plays and in his scripts is everything.

Elizabeth Berry (Natalie Portman) and Gracie Atherton-Yoo (Julianne Moore)

AA: Your films are famously film-literate, always looking to other traditions. I want to ask you about melodrama — it’s there in all your films.

TH: If that’s true, I’m so proud to have that be part of my place among the many great directors of the golden era of Hollywood, who I love and who inspire me.

It is in stories about the domestic world and how women occupy the center and are in the crosshairs of so many contradictory burdens and responsibilities where the institution of family and relationships around love and desire are all co-mingling. There’s also something where form is pushing in on the shape of the experience of the film and squeezing the people within it, compressing emotion and stifling the possibility for release. They’re also the stories of our lives because we all come from families, we all come from women, and we all come from houses of some kind or other. They’re inherently about social language and systems of pressure on people.

AA: I want to ask about Charles Melton, who plays Joe. It’s a really beautiful, devastating performance.

TH: I had dinner with Laura Rosenthal, my casting director and friend, and we’ve been conspiring on these collaborations since Velvet Goldmine in 1998. Film after film we’re given these difficult challenges of trying to find unique kinds of actors for certain roles. This happens in movies in the best circumstances where there are things you haven’t quite figured out yet yourself, or little blind spots still in your own process — people step in, and you find this person.

We just kept watching [Charles’s] tape and how much he comprehended this character. He drew from his life, his family experiences, his uncanny abilities as an actor that he himself doesn’t even fully realize the depth of. He’ll say, “Oh, Todd, I couldn’t have done that without you.” I’m like, “Charles, you taught me who Joe was.”

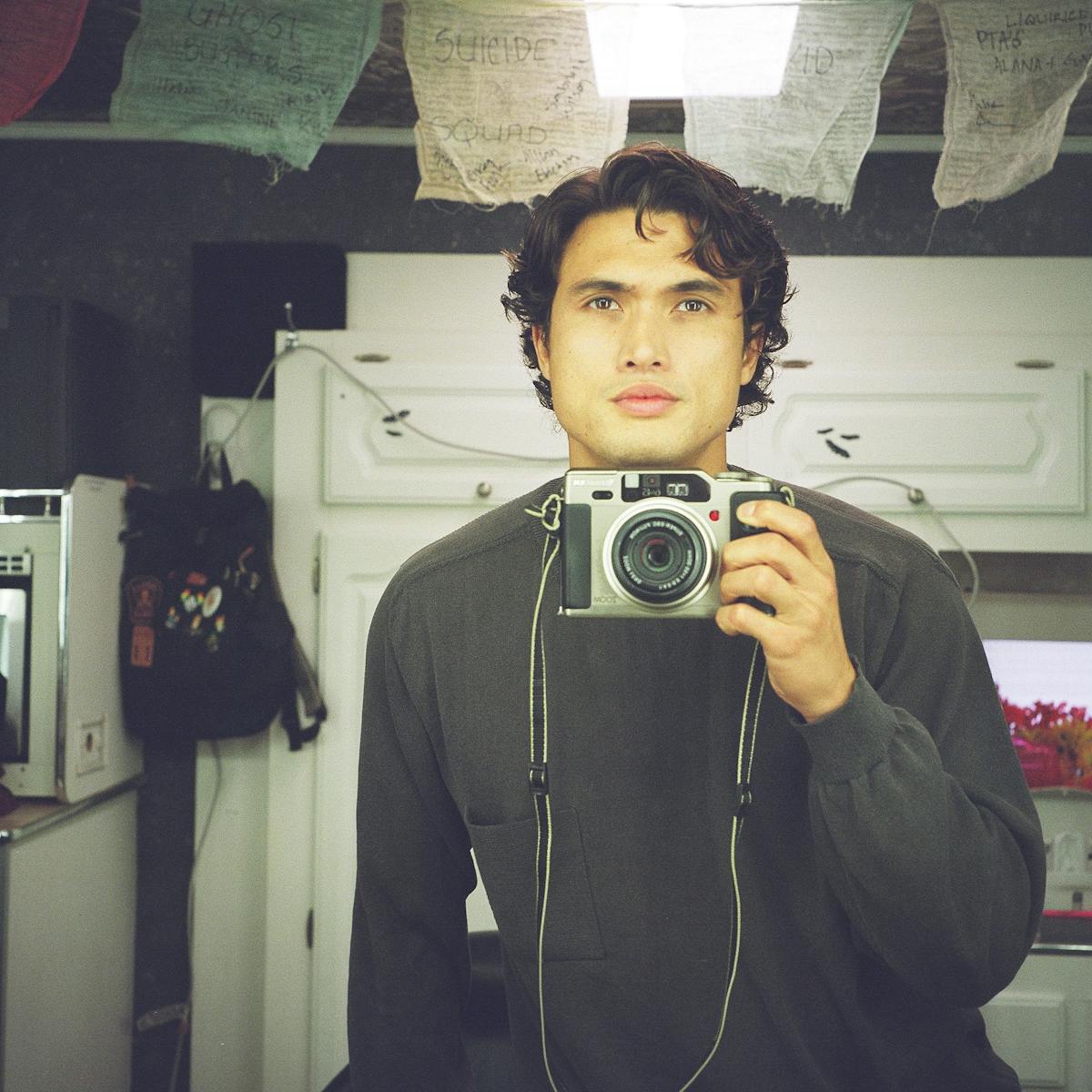

Joe Atherton-Yoo (Charles Melton)

AA: It sneaks up on you that it really is his film. I want to ask you about Monarch butterflies because it’s such a persistent motif.

TH: I was moved by it as a metaphor but felt that it needed to be undermined as well. It was an opportunity for the music to immediately confront you as a viewer: We’re not feeling too earnest about this. It makes you analyze every aspect of the frame. You read meaning and a sort of faithfulness, fatedness into everything.

AA: From the beginning, you’re encouraged to read this as camp, but right off the bat you allow what’s really upsetting about this story to sneak up on you. There are so many questions that just persist, and that’s such an important part of this film succeeding.

TH: It’s so funny, the word “camp”; it was the furthest thing from my mind. I don’t find anything camp about the film. I’m a student of camp as an idea. Camp, to me, is in the eyes of the reader. It’s an interpretive mode that reevaluates the past with a distance and a different way of reading excessive emotion.

I thought people would be like, “Oh, Todd, I love the distancing and the cold austerity of the long shots that they’re holding forever and how creepy this is.” In fact, they notice their own shifting points of view. They’re interrogating themselves as they watch the film unfold. So there isn’t that sense of being kind of pushed into a place of contemplation that’s academic, and that works.

This film would not work the way it does without these actors who I relied on beyond any reasonable risk of it failing because we had no time to do anything else. It came to Natalie’s producing partners, she sent it to me, and I was like, “Wow, I’m really interested.” All of a sudden, there was a tiny sliver that overlapped between Natalie’s schedule, Julianne’s schedule, and my own. We still didn’t have any time for rehearsal. We shot the movie in 23 days. We had a very low budget. It meant that everybody, all my creative partners and actors, was on their A game and we were all making the same film.

And I just wanted to open it all up, let everybody know what my ideas were, what the sort of language was, and go for it. I wouldn’t have ever, ever traded the experience of making it.