Director Richard Linklater reimagines a 60s childhood in the shadow of NASA.

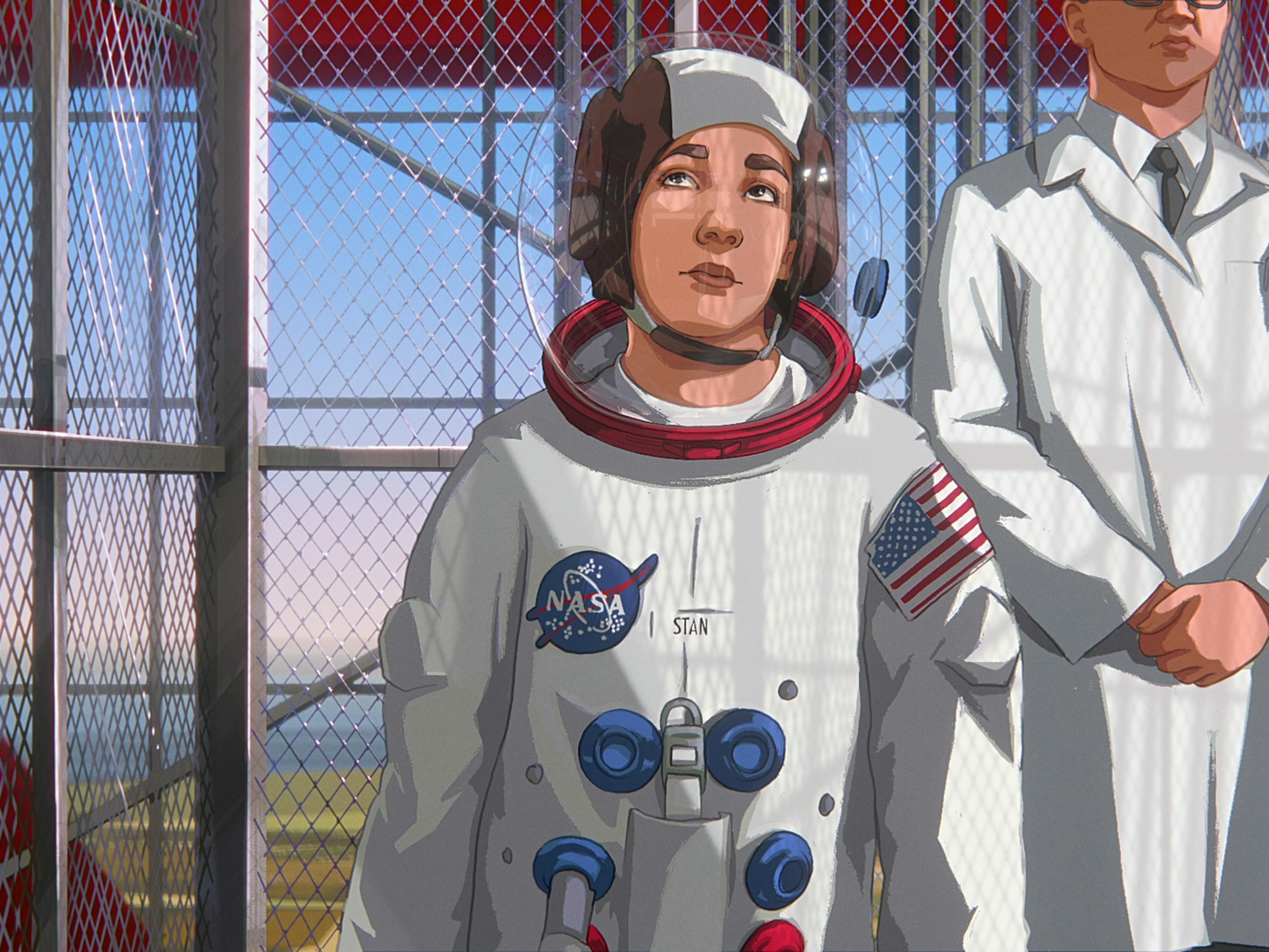

Imagine this: You’re a fourth-grader in a Houston, Texas suburb. You’re playing a game of kickball in your elementary school’s yard when two black suits approach. “We’ve scouted you on the kickball field, we spoke with your teachers. In short, we’ve selected you as the perfect candidate for this mission. We accidentally built the lunar module a little too small. But we’re not gonna let that set us back.” So begins writer-director-producer Richard Linklater’s Apollo 10 ½: A Space Age Childhood, an animated feature that tells the story of an imaginative kid named Stan. The film blurs the line between the young boy’s fantasy and real-world history to capture the full experience of growing up in the 1960s, in a sliver of time when space travel was new, and anything and everything felt possible.

Linklater got the idea for his third animated feature while writing his Oscar-winning drama Boyhood and based the film on his own experiences growing up in the Houston area at the time: “I haven’t seen a movie about growing up in the shadow of NASA. There are a lot of movies about Apollo missions — the program itself is worthy of a lot of stories. But I thought, I bet that not many filmmakers my age were living near there. They just weren’t. So I thought, That’s my story to tell.”

Apollo 10 ½: A Space Age Childhood is narrated from 50 years into the future by Jack Black (as a reflective older Stan) and follows the character as he tests the too-small lunar module in a top-secret mission. The young astronaut returns to Earth in time to watch Apollo 11 blast off with his family, including a father who works at NASA, a stay-at-home mom, and five older siblings. The story transports audiences back to the 60s through childhood memories: the novelty of push-button telephones, the rise of the Jell-O mold craze, Saturday morning cartoons, and the construction of the Houston Astrodome, complete with the world’s first AstroTurf field. Everything — even grass — was ripe for innovation, and it seemed that if you could dream it, there was a good chance you could do it, too. As Stan says in the film, “The optimistic technological future was now, and we were at the absolute center of everything new and better.”

Linklater joined forces with longtime collaborator Tommy Pallotta (producer, head of animation) to realize his space-age script in a style that felt true to the period and could be used to animate actual archival footage. “The discussion was, How do we make the animated footage feel old and degraded and lo-fi and analog, and how far do we push that? So that was really the design approach,” says Pallotta.

Linklater and Pallotta opted to wash Apollo 10 ½: A Space Age Childhood in the era’s palette (“We were really trying to capture that Kodachrome 40 look and the home movies and the colorful era,” says Linklater). According to Pallotta: “The thing that really strikes me is how much brown, green — avocado green — and this really bright yellow were in this film, which really were the colors of that time.”

Although Pallotta is recognized for co-developing the first digital rotoscope technique — which he and Linklater employed in the director’s earlier animated ventures, 2001’s Waking Life and 2006’s A Scanner Darkly — the pair decided that 2D styles with minimal 3D and performance capture would be better suited to the period. “There are no new techniques at all in this film,” says Pallotta. “The software that we used to do most of the animation is TVPaint. Anybody can use it today. We never set out to make the most technologically advanced animated film. In fact, a lot of times we made choices that were the lo-fi version.” Adds Linklater, “While it was always the longer, more time-consuming answer to every problem, the handmade choice was always the right one.”

Houston-based animation studio Minnow Mountain co-founders Steph Swope and Craig Staggs served as producers for Apollo 10 ½: A Space Age Childhood, with Staggs also heading up character animation. Their team went frame by frame to capture and animate the footage of Stan, his mission, and the time he spends with his family, as well as archival footage, including news clips of the Vietnam War and its protests, and the moon landing. The animators even redrew still images of period advertisements and astronaut headshots to lend the film an impressive specificity. “We’re not making Hanna-Barbera Saturday Morning Cartoons,” says Staggs. “We’re making cinema, and it’s big, and it has epic scale, and it’s touching, and it’s emotional, and wow, what a treat to get to do that kind of content.”

Apollo 10 ½: A Space Age Childhood’s realistic style does allow the film to transcend animation, into the category of cinema. Says Swope, “I’m hoping that with this film, parents watch it with their kids, and folks get lost in the movie. That’s the beauty of what we do, too, that you can kind of forget that it’s not just a live-action movie until something happens that is out of that field and wild. It goes back to that freedom of being able to do anything [in animation] and people will just go along with you on the ride.”

NASA’s Apollo launches, humankind’s very first steps on the moon, imbued Americans with a sense that they were on the precipice of something monumental. Linklater’s film fully preserves that sentiment and returns us to the moment. “When Kennedy gives his speech, it still gives me goosebumps,” remembers Pallotta of J.F.K.’s Rice University speech on space exploration, which is depicted in the film. “When he says, ‘It’s not because it’s easy, it’s because it’s hard,’ it reminds me of why we were making the movie and the way that we were making it.”