Crafting an unconventional and powerful love story.

To bring Maestro to life, it took an extraordinary crew dedicated to filmmaker Bradley Cooper’s singular vision for his virtuosic study of the love story between legendary conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein and his wife, the actor, artist, and activist Felicia Montealegre Cohn Bernstein. Each and every craft had to be in lockstep to serve that vision, building on years of rigorous research to convey the profound and uncommon bond Leonard and Felicia shared.

It was that bond that proved to be the key to understanding the iconic cultural figure. How did the intimate relationships in Leonard’s life fuel his creative fire? What of the family life that grounded him while his professional profile skyrocketed?

To explore those questions, Cooper assembled an all-star team in front of and behind the camera, including actors Carey Mulligan, Matt Bomer, Sarah Silverman, and Maya Hawke; screenwriter Josh Singer; cinematographer Matthew Libatique; production designer Kevin Thompson; costume designer Mark Bridges; makeup designer Kazu Hiro; film editor Michelle Tesoro; and sound designers Steven Morrow, Tom Ozanich, Dean Zupancic, Jason Ruder, and Richard King.

The cast and crew of Maestro

IT STARTED WITH A VISION

Bradley Cooper, Director

Bradley Cooper on set

In his career as an actor, Cooper has always found himself lingering on set between shots, hungry for insight into the process of directing from filmmakers including Clint Eastwood, Paul Thomas Anderson, Todd Phillips, and Guillermo del Toro. He brought that wealth of experience to bear on his debut feature, A Star Is Born, and indeed, it was the confidence and courage he displayed with that film that led producer Steven Spielberg to declare him the person to bring Maestro to the masses.

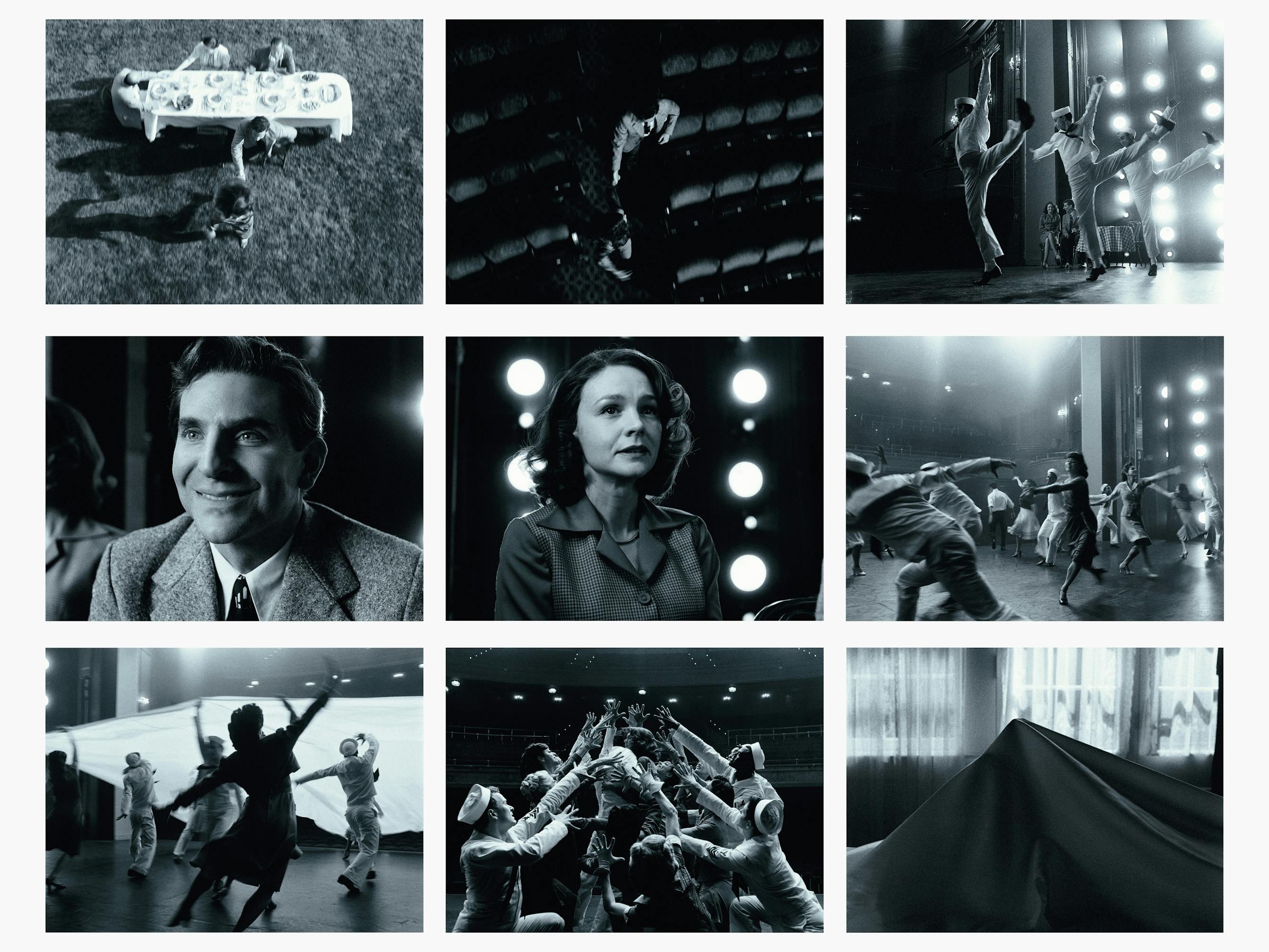

It was important to Cooper that the cinema of Maestro, its visual storytelling, feel like a memory, like an imagining of its many time periods. His inspirations ranged from Ernst Lubitsch to Hal Ashby and Sidney Lumet. The overall visual motif was “foreground-background,” Cooper says, in that Leonard is always heading toward something or being pulled away from something. He spent years crafting that aesthetic with his collaborators before executing it during production with a level of fearlessness he says he’s never felt as an artist. Whether it was shooting a four-minute argument between Leonard and Felicia in a single take with no coverage, or embracing a striking dual-palette approach that would depict half of the story in black and white and half in color, Cooper trusted his instincts — and the spirit of Leonard — to guide him through.

“I take joy in everybody feeling like they are part of facilitating a vision. I love being a part of the acting side of that and helping a director to help fulfill their vision, but as a director myself, I like to create a world where everybody comes to work and they feel like their idea might be a major part of this movie.” — Bradley Cooper

IT STARTED WITH THE LETTERS

Original Screenplay, Bradley Cooper & Josh Singer

Letter from Felicia Montealegre Cohn Bernstein to Leonard Bernstein

Oscar-winning screenwriter Singer (Spotlight) knows the power of research when it comes to depictions of historical events and figures onscreen. Maestro, which he co-wrote with Cooper, would take him deeper than ever, and the fruit of their study would find its way into the screenplay in profound ways. For example, John Gruen’s photo book The Private World of Leonard Bernstein, published in 1968, provided an invaluable peek into the lives of the Bernsteins at an idyllic time in the late-1960s. The Bernsteins’ 1955 Person to Person interview with journalist Edward R. Murrow was also an amazing resource.

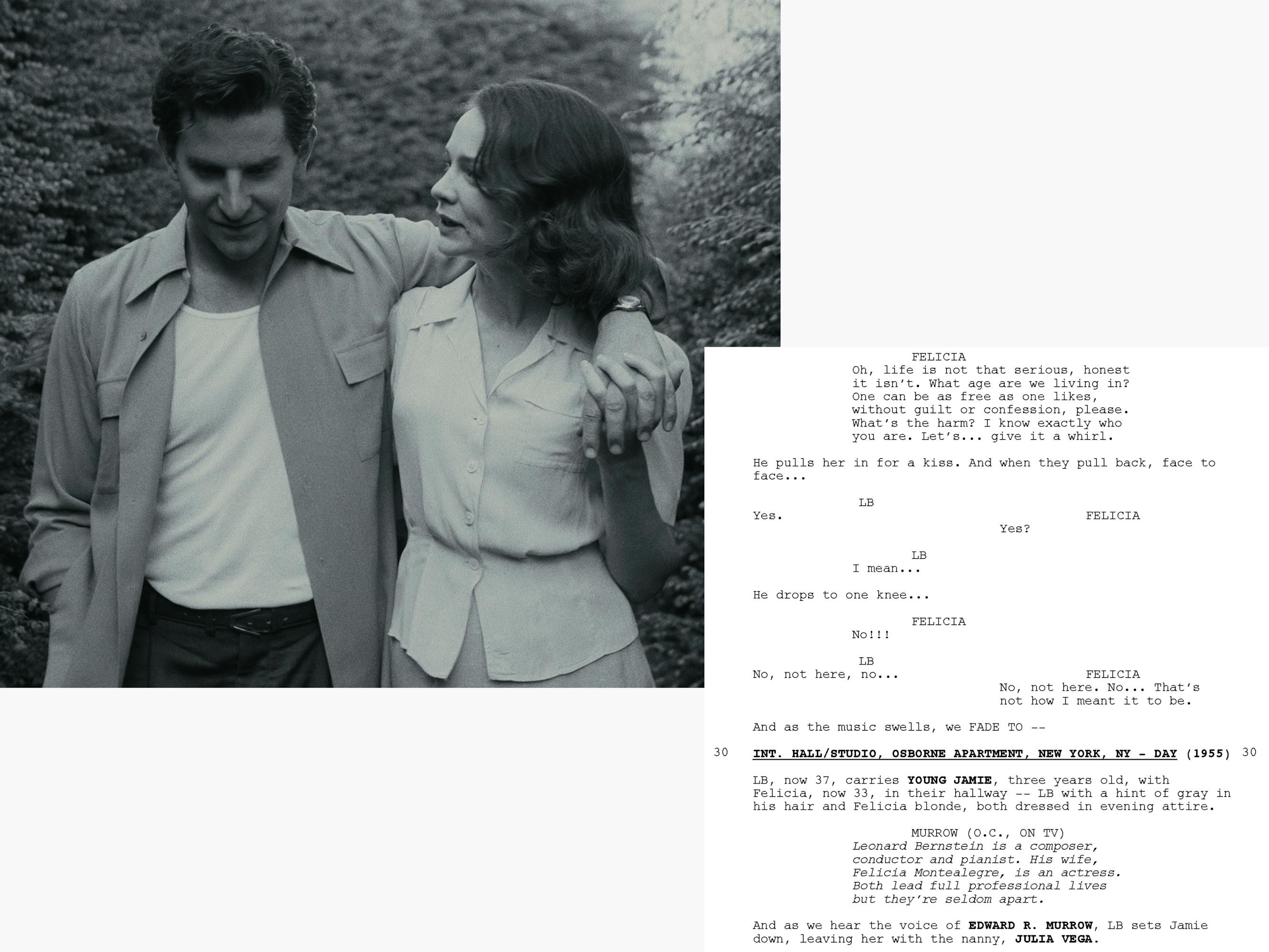

Leonard Bernstein (Bradley Cooper) and Felicia Montealegre Cohn Bernstein (Carey Mulligan)

Mark Horowitz, curator of The Leonard Bernstein Collection at the Library of Congress, was a godsend, particularly as the Library had recently unsealed a series of letters that had not been opened for a quarter century. They revealed Leonard in full candor through exchanges with former lover and lifelong friend David Oppenheim and other contemporaries. There was, in particular, a letter from Felicia just after the two had married, in the wake of a fight. “I happen to love you very much as you are,” she wrote. “Let’s give it a whirl.” That last phrase made it into the script for Maestro.

“I think Bradley found something really stunning and inspiring in this modern love that Lenny and Felicia had, which was groundbreaking for the time. Even for today, it’s a paradigm that is not really explored, about a man who had huge appetites but needed family. There’s certainly plenty of tape on Lenny if you want to explore all the ways in which he talks about music or composing or conducting, but if you really focus on his private life, you get to know the man in a way that those tapes don’t allow for.” — Josh Singer

Read the full script here.

IT STARTED WITH CHEMISTRY

Acting, Carey Mulligan & Bradley Cooper

Felicia Montealegre Cohn Bernstein (Carey Mulligan) and Leonard Bernstein (Bradley Cooper)

Cooper and Mulligan went to great lengths to achieve a seamless authenticity in their embodiment of Leonard and Felicia on screen. The two first discussed the role over breakfast at Cafe Cluny in the West Village in 2018 where Cooper shared his thoughts about wanting to make a film about marriage. Shortly after, they went to Philadelphia to narrate Candide with conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin, the music director of the Metropolitan Opera, the Philadelphia Orchestra, and the Orchestre Métropolitain of Montreal. It was over these three performances that their bond and their characters started to form.

The duo participated in a five-day dream workshop, exploring their subconscious together and unlocking the connection between each other and their characters. They dug into the couple’s correspondence at the Library of Congress. That trove also provided insight into Leonard’s lasting bond with Oppenheim, played by Bomer in the film. Bomer even hand-wrote a number of the letters himself and would give them to Cooper on set as a way of maintaining that bond as actors.

Cooper and Mulligan also enlisted the services of acclaimed dialect coach Tim Monich. Cooper worked closely with Monich to achieve Leonard’s trademark cadence and vernacular, as well as the evolution of his voice over the nearly four-decade period covered in the film.

To capture the authenticity of Leonard’s conducting, Cooper worked with Gustavo Dudamel, music and artistic director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, as well as Nézet-Séguin, attending dozens of rehearsals and performances to learn their techniques. The finale of this preparation would be recreating Leonard’s renowned 1973 performance of Mahler’s “Resurrection” at Ely Cathedral in England. Cooper would ultimately spend six years learning how to conduct six minutes and 20 seconds of music with the London Symphony Orchestra for the scene.

“The lack of fear was key to the whole thing; Bradley just made you feel like you could completely fall on your ass and it didn’t matter. He was so incisive with steers he would give, or in a scene, he would push a narrative or push a line in a way that would trigger something else in you.” — Carey Mulligan

IT STARTED WITH A FRAME

Cinematography, Matthew Libatique

Leonard Bernstein (Bradley Cooper)

For his right-hand collaborator behind the camera, Cooper again enlisted his Oscar-nominated A Star Is Born cinematographer Libatique. The conceit behind telling the story of Maestro visually would be two-pronged . . . literally. The first half of the film depicting a young Leonard falling in love with Felicia and rocketing to global stardom would be captured in black and white, while the second half, depicting the relationship’s hardships and Leonard’s tormented struggle as an artist, would be rendered in color.

A series of early tests resulted in the decision to shoot on film. For the black-and-white portion, Libatique wanted to avoid making it look like an old movie and instead an actual reality. To that end, he leaned on photographs instead of cinema, particularly the photographs in The Private World of Leonard Bernstein as well as the candid black-and-white work of photographer Elliott Erwitt. He relied on early lighting techniques and a contrast glass to ensure the light properly bounced off the actors’ faces and the sets.

The color portion of Maestro involved exposing and rating the color film to give it a period look. The palette created by production designer Thompson and costume designer Bridges gave Libatique a rich texture and depth to capture with his lens.

He and Cooper make bold choices in the framing and use of limited coverage, resulting in poetic long shots highlighting the drama in the film’s most intimate scenes. One of the most daunting scenes to shoot was the Ely Cathedral scene, which initially involved a cable cam and multiple coverage angles, but ended up being a one-take Technocrane shot that made it into the film.

“The film has a progression to it, from the aspect ratio of 1.33:1 in black and white to the 1.33 in color and then, finally, to the 1.85 in color. And I’m actually as proud of the color photography as I am of the black-and-white photography. I used a stock that I was familiar with to try to create almost a period look through the way I rated the film and the way I exposed it.” — Matthew Libatique

IT STARTED WITH A PLAN

Production Design, Kevin Thompson

Inside the Bernsteins' apartment

Authenticity was key to every aspect of Maestro. That meant a lot of location shooting, but production designer Thompson and his art department were still tasked with a number of significant set builds that would help tell Leonard’s story in dynamic ways.

The work is on display from the beginning, when Leonard receives the fateful call that he is to fill in for Bruno Walter to conduct the New York Philharmonic in Carnegie Hall. The moment finds him living in an apartment above the Hall, and the way Cooper designed it, the camera had to move along a specific path to ultimately reveal the legendary space. Thompson then adapted his design to that vision to allow for camera rigging and equipment.

The Bernstein residences in the Osborne and Dakota apartment buildings were another matter. Without having the access and permission to film there, Thompson adapted the floor plans and then built them with his team from the ground up. The entire apartment is outfitted with period authentic books, awards, and family photographs, including replicas of Leonard’s Grammys created for the film.

“The legendary apartment the Bernsteins lived in at the Dakota was entirely recreated on a sound stage. We used this set to introduce color into the movie. Despite the spaces’ grandeur, we still wanted the rooms to feel bohemian and cultured as opposed to pretentious or nouveau riche. We recreated the light fixtures, hardware, furniture, wall treatments, and art that the couple had in their actual apartment and made sure that the models of the piano and harpsichord were also the same as what Lenny had in the home.” — Kevin Thompson

IT STARTED WITH A SKETCH

Costume Design, Mark Bridges

Just like the production design, the costume design of Maestro, courtesy of Oscar winner Bridges (Phantom Thread, The Artist), is meant to convey both character and the passage of time. Bridges describes his work at imagining looks from the past as “forensic costume design.” The research involved hands-on investigation of the Bernsteins’ actual clothing items, still in their closet in Fairfield, Connecticut. Bridges also pulled tons of photo references and would go through marking “the beats of a lifetime,” noting how the twists and turns in the story would reflect on the style of the characters as they moved through it.

One of the challenges was navigating the way textures and colors would read in the black-and-white portion of the film, but Bridges was able to draw from his previous experience with The Artist in finding the right equation for contrast with his color selections. And then, as Leonard drifts farther away from Felicia in the latter half of the film, his outfits begin to lean more flamboyant and less conventional. “Left to my own devices, I’d be dressed as a clown,” he says in the film, which is demonstrated in the evolution of his costume design.

Bradley Cooper and Mark Bridges

Bridges creates a sense of timeless glamor with Felicia’s wardrobe, putting her in striking blue dresses throughout the film and working with Chanel to recreate an iconic tweed suit. It was a detail written into the script, reflecting a woman of style who would wear clothing as armor, Bridges explains, almost as if to say, “I couldn’t possibly receive bad news if I look fabulous.”

“A lot of the research is just finding out who these people are and how they present themselves to the world. Does it seem like he always wears a turtleneck when he’s rehearsing because theaters are drafty? Felicia looked well-tailored since the 1940s and continued to be as Mrs. Maestro right up to the time of her passing. What does that say about her? You learn about the characters and then you’re able to make choices about what they would wear.” — Mark Bridges

IT STARTED WITH A TEST

Hair & Makeup: Kazu Hiro, Leonard Bernstein Prosthetic Makeup Designer; Sian Grigg, Make-up Department Head; Kay Georgiou, Hair Department Head; Lori McCoy-Bell, Hairstylist for Mr. Cooper

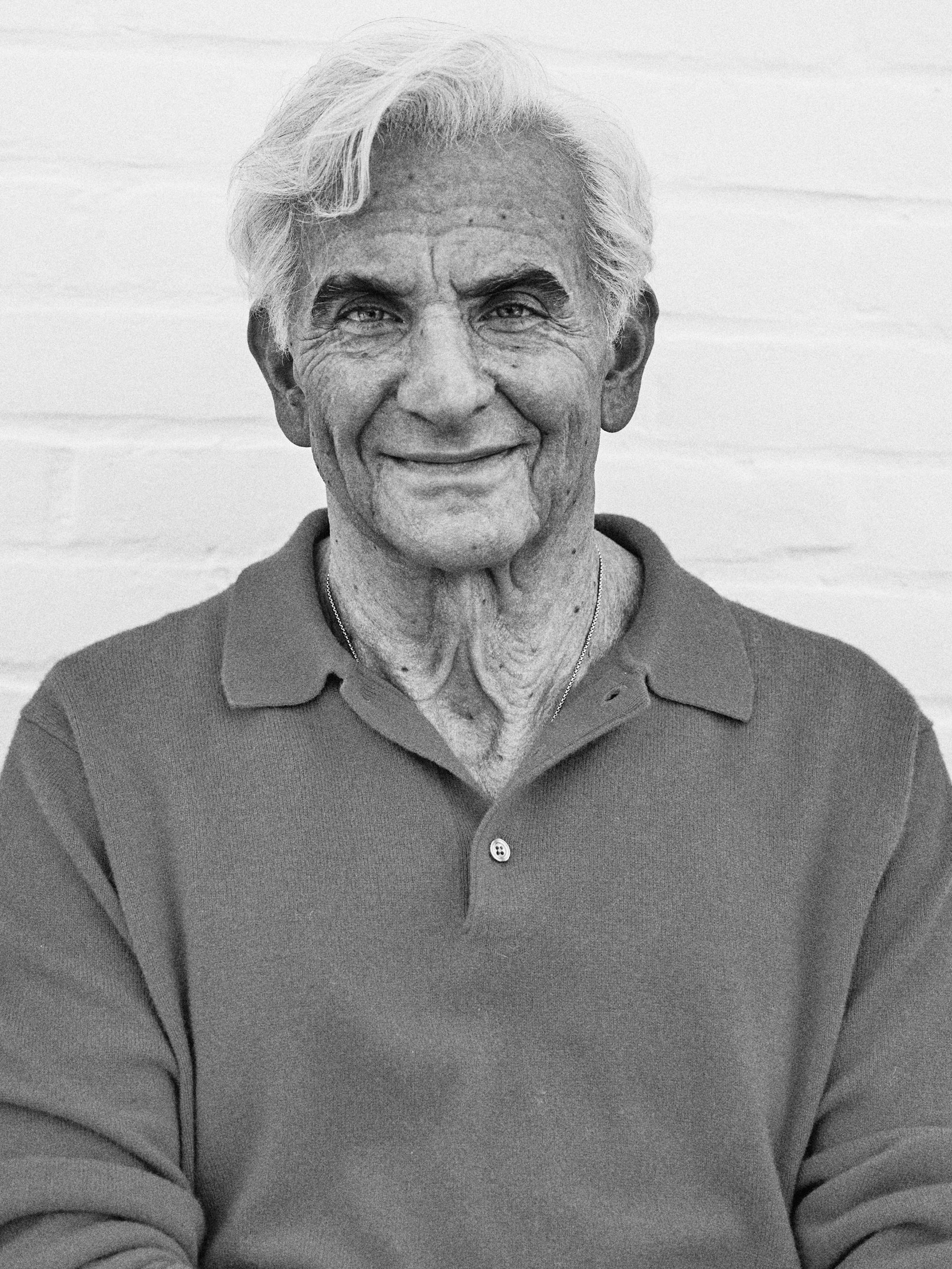

Leonard Bernstein (Bradley Cooper)

When it came to bringing the visage of Leonard to life through makeup and hair, there was only one choice. At the recommendation of his Nightmare Alley director del Toro, Cooper turned to Oscar-winning makeup designer Hiro, whose work includes The Darkest Hour and Bombshell among many others. As fate would have it, Hiro had long been a fan of Leonard since watching a documentary when he was 16 living in Japan. Hiro recognized the immense commitment and dedication of Leonard and saw the composer as an inspiration.

Cooper and Hiro worked for more than three years to perfect Cooper’s physical transformation, with Hiro poring over some 1,500 photographs while studying any archival video available to him. It started with a screen test at the Walt Disney Concert Hall with Cooper, Spielberg, and music director Dudamel. From there, Hiro designed five distinct stages to depict Leonard’s evolving appearance over the film, where he ages 45 years from 25 to 70 years old. The prosthetics for Cooper took anywhere from two to five hours to apply, depending on Leonard’s age being depicted. All in all, Hiro crafted 137 individual prosthetic pieces, ranging from small to large for test makeup, film test, and filming. The final stage showing Leonard in 1989 included prosthetics for the top of the head, forehead, nose, upper and lower lips/chin, cheeks, neck, back of the neck, shoulders, earlobes, hands, and arms — as well as a bodysuit.

“Lenny’s passion and drive resonated with me deeply, inspiring me to pursue my dreams with unwavering determination. I always harbored a hope that one day I’d have the opportunity to work on a film dedicated to him.” — Kazu Hiro

IT STARTED WITH RHYTHM

Editing, Michelle Tesoro

Felicia Montealegre Cohn Bernstein (Carey Mulligan) and Leonard Bernstein (Bradley Cooper)

The work of film editor Tesoro started well before a single camera rolled on Maestro. More than a year ahead of shooting, she began exploring what the aesthetic of the film would be through Cooper and Libatique’s proof-of-concept package, which included photos of Leonard along with documentary footage, camera tests, hair and makeup tests, and more. In the end, this process helped inform what would actually be shot.

Felicia Montealegre Cohn Bernstein (Carey Mulligan)

The spine of the story was the relationship between Leonard and Felicia. The editing is telling that story from the outset, with the decision to frame the film with a 1980 60 Minutes interview session as Leonard looks back on his life and career two years after Felicia’s death. From there, the audience is swept into the first of Maestro’s two distinct sections charting Leonard’s professional ascendancy and the magic of his budding relationship with Felicia. The rhythm of this section reflects the rush of new love and discovery, only to recede for the next section with a more grounded, restrained approach that channels the complexities of Leonard and Felicia’s life together and the profound sense of compromise that comes with it.

The editing of the film was deeply influenced by Leonard’s own music. Taking a lyrical approach, the pacing of the film effortlessly takes us through four decades in two hours.

“By listening to this music, you inherently have that inside of you. Because when you’re cutting, you’re just sort of cutting on instinct. And oftentimes, Bradley and I had those feelings in the same place. We were in sync. But I think that is because we were so into the music itself. It channeled itself through us.” — Michelle Tesoro

IT STARTED WITH THE MUSIC

Sound; Steven Morrow, Tom Ozanich, Dean Zupancic, Jason Ruder and Richard King

Leonard Bernstein (Bradley Cooper)

Leonard once commented that he was not interested in having an orchestra sound like itself, but rather, he wanted it to sound like the composer. That would be key insight into how sound would function in Maestro: as part of the storytelling tapestry, yes, but more importantly, as a representational element of the figures onscreen. Enter the sound team, which includes Oscar-nominated mixers Morrow, Ozanich, and Zupancic, Oscar-nominated music editor Ruder, and Oscar-winning sound editor King.

The goal with the symphony scenes was to record the material live, a daunting prospect for the sound team. The Mahler “Resurrection” symphony in Ely Cathedral, for example, was a considerable challenge. It’s a cavernous space with less-than-ideal acoustics, but the idea was to put the audience right in the middle of that orchestra so that they would hear the power of the music, just as Leonard would have heard it in 1973. Sixty-one microphones were used to record the orchestra alone. Microphones that appear on camera, for the opera singers and the choir, were correct to the time period and were additionally tasked to be functional.

Leonard Bernstein (Bradley Cooper)

Meanwhile, sequences like Leonard and Felicia’s first “date,” which takes the couple to the empty Cherry Lane Theatre, provided the opportunity for counterpoint. Tweaking the aural landscape with reverb and echo and subtle editorial elements like the low buzz of a stage light created a sense of isolation for these two people falling in love, far away from the rest of the world.

“I like to describe the mix as a reflection of Leonard Bernstein, being that he was a dynamic personality but an elegant man. The elegance is reflected in the subtle scenes, where everything is very quiet and intimate and then there might be the dynamic of a burst of wind when Lenny and Felicia are on the balcony when he’s a bit melancholy. Then there is the bombast of Ely Cathedral. Then out of Ely, we go right to the waiting room at the doctor’s office. We’re on these huge rides, and then there are big dips of emotion.” — Dean Zupancic

Watch Maestro on Netflix now.

Listen to Bradley Cooper discuss the process of transforming both physically and emotionally into Leonard Bernstein on the Skip Intro podcast.

Learn more about how Bradley Cooper and Josh Singer approached the extensive research process of writing the screenplay for Maestro.

Listen to Carey Mulligan unpack the process of fully immersing herself in the role of Felicia Montealegre Cohn Bernstein on the Skip Intro podcast.

Watch the cast of Maestro discuss the making of the poignant love story.

Listen to more with the crafts team of Maestro on a special episode of Skip Intro.

Watch the sound team unpack the complex sound mix of Maestro in conversation with Bradley Cooper.