Julia Willoughby Nason documents the high-profile tragedies of Hampton, South Carolina with the help of those who were closely affected.

Julia Willoughby Nason is no stranger to the American obsession with true crime. Before diving into the small-town systems of Hampton, South Carolina with the new mini-series Murdaugh Murders: A Southern Scandal, the director turned the camera on some of the past decade’s favorite white-collar criminals: Fyre Festival founder Billy McFarland in 2019’s Fyre Fraud and famed legging pyramid scheme LuLaRoe in the 2021 miniseries LuLaRich. “The reason it can be ‘entertaining’ to watch scammer stories that have crime without murder is the dark comedic relief within the power structures,” Nason says over Zoom. “All this stuff is Dadaesque.”

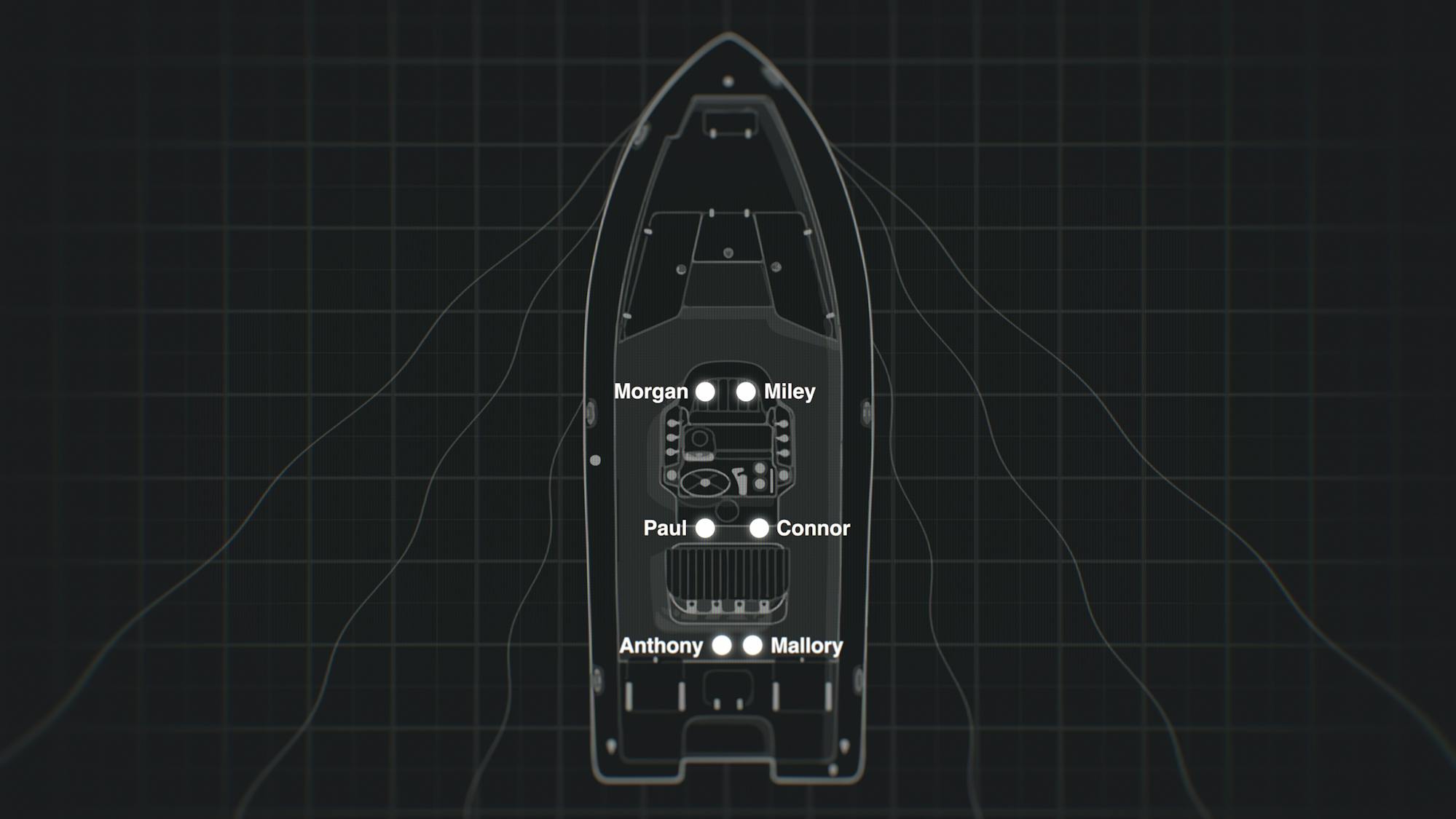

But Murdaugh Murders presents a narrative more winding and devastating than mere fraud. The three-part series takes us inside the dark story of the prominent local Murdaugh family, chronicling the notable events — including a boat crash that claimed the life of 19-year-old Mallory Beach — that preceded the widely-covered deaths of youngest child Paul and matriarch Maggie Murdaugh.

The docuseries offers unique access to the individuals who make up the fabric of the community, as we witness the tragedies through the eyes of friends, family, and locals — particularly the young adults closest to Paul, who had been driving the boat. Thanks to the deft use of original archival footage and intimate interviews, we enter the story from an entirely new vantage point.

“As filmmakers, we are looking for fascinating stories about social justice,” Nason says of her past work (Time: The Kalief Browder Story, The Pharmacist, Rest in Power: The Trayvon Martin Story). “The consistent thread is the courage of the subjects to expose their lives on camera, especially when it’s one of the most traumatic events in their lives.”

Nason sat down with Queue to discuss the role of art in accountability, and what it’s like to release a documentary at the same time as an ongoing murder trial.

An edited version of the conversation follows.

Emma Holland: You focus most of the series on the boat crash. Why do you think that event broke the whole cycle of crime?

Julia Willoughby Nason: The boat crash was this unexpected event that touched a nerve in the community. Things like this in the Murdaugh family — in terms of patterns of cover-up — were very consistent over the years, but this one didn’t fly. You had the elements that could get the attention of a community: a young, beautiful, white, blonde girl who was tragically killed; a small, tight-knit community in South Carolina; all the young adults on the boat were from a certain class, but the driver of the boat was from a higher class. The people on the ground, the families, they said, “Not this time.”

Why did you decide to tell the story as a three-part series?

JWN: There was so much meat on the bone storywise that we could have made it even longer than three parts, but we wanted to scale it down so that we could really keep it tight on the boat crash. We really didn’t want to focus so much on Alex Murdaugh because we felt that’s what everybody in the media was already doing, and the heart of the story really was with Morgan and the young adults who were on the boat. Because we had such intimate, exclusive access to them, we really wanted to sit and have them lead the whole heart of the story, as opposed to just talking about crime.

You did a fantastic job of leaving that question of complicity open-ended. Can you talk about how you thought about that while centering the kids and these families who had grown up with the Murdaughs for decades?

JWN: A lot of people hung out with the Murdaughs — you got to play with their toys and be amongst very affluent people. Some people say the Murdaughs were super generous and that they always gave back to the community. Hampton is not really a bustling town, but the Murdaughs would throw fundraisers and have cookouts, and it was like they were the mayors of this South Carolina area. People that worked for the Murdaughs worked for them for a very long time. There was a lot of loyalty there.

The friend group was interesting because they were from different classes, and the Murdaughs were seemingly untouchable in the community compared to the other families, even though they, and their parents, had all grown up together. The Murdaughs were lawyers, and none of the other kids’ parents were. That’s a big difference, especially when there’s a tragedy involved. As we saw, when lawyers and law enforcement — who usually know each other very well — go into a crime investigation, there’s a natural tip of the hand as to who may get preferability on certain matters. But a lot of people talk about how the boat crash was when people got fed up with that type of turning the other cheek because someone they knew and loved was actually killed and no one was taking responsibility for it.

What was getting access like?

JWN: Morgan and the young adults on the boat did not want to talk. The media had reached out to them so much, and they had been harassed in the community because there was this divide in the town: You were either on the Murdaugh side or you were on Mallory’s side. They were so traumatized that they were like, “We are not opening up at all.” We are very grateful that [Paul’s ex-girlfriend] Morgan [Doughty] did talk to us. She knew our work. She knew that we were going to sit with her, and all of them, for a very long time in interviews and take our time.

The story is about this really old-school family and these antiquated institutions, and then you use very modern stylistic choices, like Snapchat clips and social media interfaces. Can you talk about the generational separation?

JWN: We put social media in to wake the viewer up, and also to relate to a viewer. And this is actually what Morgan and the other kids on the boat had: this social media as their original archive. We wanted to have that be the guiding light and dictate the pacing in a lot of ways, but contrasted against a very established, romantic landscape that has had historical ties for generations.

How did you decide where to end the story, especially with the Alex Murdaugh trial going on?

JWN: When we were making this, he hadn’t even been indicted yet. But we wanted to end it for the audience to decide what is there in the story. When you go into these docs, it’s like the kitchen sink. Look at everything, research the 300-year history of this, this person’s

psychology, how these people are connected, and [how] this person dated the person that knew this. And then it’s all about reducing to the essence. It’s like taking spices that are whole and, with a mortar and pestle, just continuing to refine them down to a golden powder of taste.

It’s this hyper-local story, yet I imagine that it reminds people all over the country of something in their own towns. Do you see this making people question the systems at play in their own communities?

JWN: With all of our work, we start with the most intimate portraits of the character, to bump us out into systematic analysis or abuse. This story is a very small-town portrait — but the psychology around the abuse of power is true in any community, big or small. It’s very American dream mixed with America’s original sin.