Queue heads into the studio to witness the hatching of an all-new Chicken Run adventure, Dawn of the Nugget — Aardman’s most ambitious movie yet.

Things are not looking good for Ginger the chicken. When audiences last saw her at the end of 2000’s stop-motion blockbuster Chicken Run, she had literally flown the coop, leading her flock in an audacious bid for freedom from the evil Mrs. Tweedy’s pie-making operation, and found sanctuary for them all on a secluded island. But clearly that happy ending didn’t last.

I stand at the center of Aardman Features studio, a large but unassuming building in a business park just north of Bristol, U.K. I’m here to observe the creation of Chicken Run’s long-awaited sequel, Dawn of the Nugget, and have found Ginger, her signature woolly hat still in place, manacled by her wings and legs to a nasty-looking machine. All counters, switches, and buttons, it wouldn’t look out of place in a 1960s spy movie. As suggested by a large dial that reads “active brain levels” — and the hypnotic spirals that decorate Ginger’s eyeballs — this is some kind of mind-scrambling device. In other words, it’s going to mess with this heroic hen’s greatest asset.

Ginger’s torturer, in a sense, is one of the animation supervisors, Ian Whitlock, who’s worked on most of Aardman’s films and is now overseeing all the slow, painstaking work that goes into bringing this 10-inch-tall clay-and-silicone model to life via stop-frame animation. Whitlock explains how challenging this particular scene has been. “The thing is, her eyes start spinning out,” he says. “So we’ve had to figure out how to do it on this set because you have to get in from behind, where there are a few knobs you can pull on to twist them.” The problem being, Ginger’s resin eyeballs need to be regularly replaced due to the stresses of this meticulous process, and with the camera pulled in so tight, Whitlock continues, “you’ve got to be really careful. Any little imperfection shows up. We embrace the handmade quality — we always have done — but you don’t want things to be boiling around all over the place. You have to keep a close eye on things.”

Behind the scenes with Rocky

“For us as a studio, Chicken Run was a giant step. It moved our little cottage industry to this industrial scale. But it wasn’t nearly as much as what Sam has been dealing with on Dawn of the Nugget.

Nick Park

Rocky (Zachary Levi), Nick (Romesh Ranganathan), and Fetcher (Daniel Mays)

This is the Aardman way: exacting, handcrafted, and quietly innovative. It’s how they’ve approached all their movies after Chicken Run and so spectacularly propelled the studio, previously best known for its Wallace & Gromit shorts, into the feature-filmmaking sphere. Making $225 million worldwide, Chicken Run remains the most successful stop-motion movie ever made. With this sequel, and its expansive storytelling ambition, they’ve had to push themselves further than ever before.

“For us as a studio, Chicken Run was a giant step,” says Oscar winner Nick Park, the stop-motion genius who directed the first installment with Aardman co-founder and creative director Peter Lord and, together with him, is executive-producing the sequel. “It moved our little cottage industry to this industrial scale. But it wasn’t nearly as much as what Sam has been dealing with on Dawn of the Nugget.”

Park is referring to director Sam Fell, who, like most of the crew I meet, worked on the original over 20 years ago (though Fell confesses he only animated a single sequence: American circus rooster Rocky riding a tricycle down a hill). Since then, Fell has stretched his wings, directing Aardman’s first C.G.I. feature, Flushed Away, as well as The Tale of Despereaux and ParaNorman outside the studio. “I’d been off doing other things with other people,” he says during a well-deserved coffee break from hen-wrangling. “But I’d always kept in touch. And all the way through the century they’d been talking about a Chicken Run sequel.”

The idea first came up when the original was released. Jeffrey Katzenberg, head of DreamWorks Animation (which produced the original film), asked Park and Lord what sequel ideas they had. “We were completely unprepared for that question,” Lord admits. “We just looked at him blankly and said, ‘Yeah, right, okay, we’ll get on to it.’ And 20 years later we finally achieved it!” he laughs.

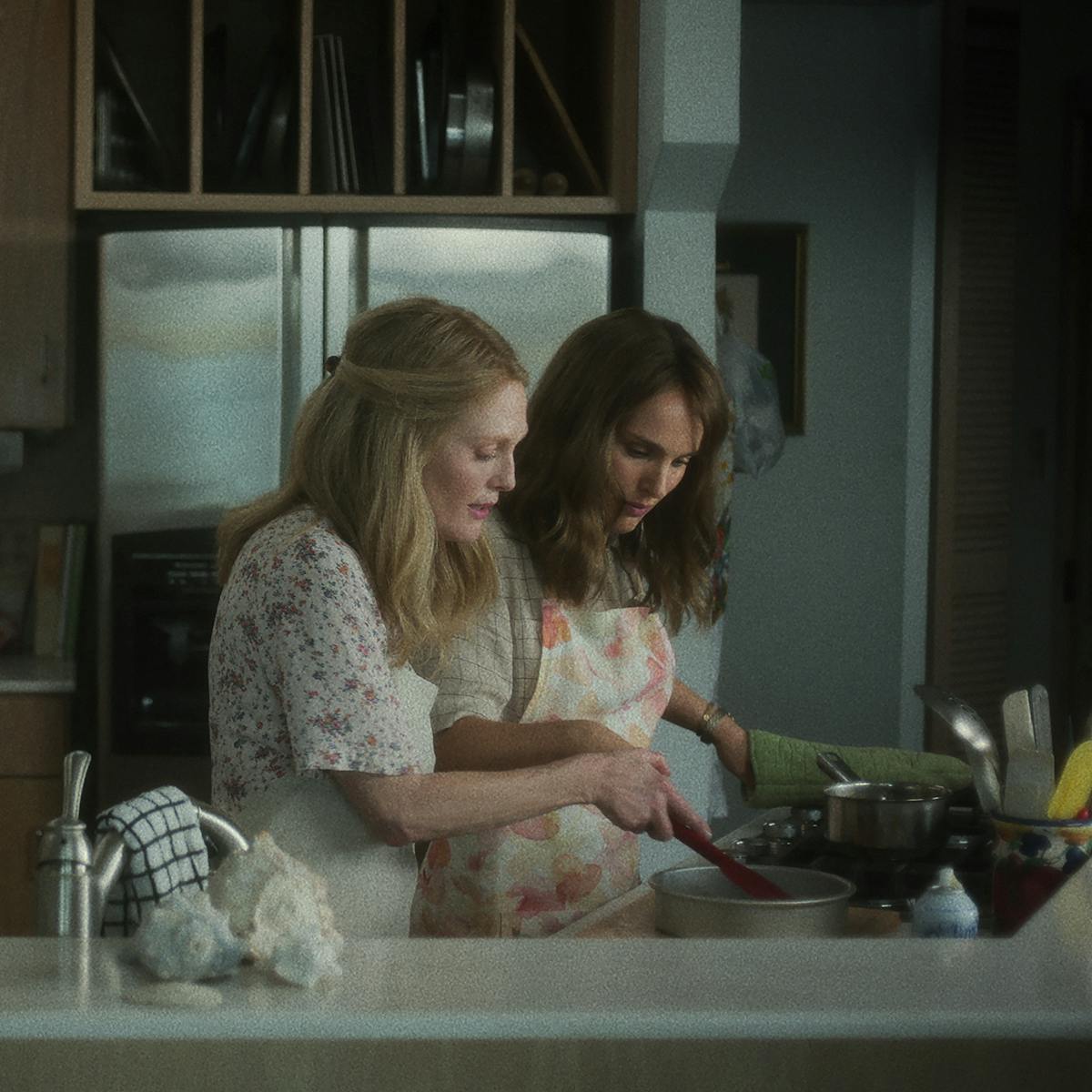

Behind the scenes with Reginald Smith, Mrs. Tweedy, and Dr. Fry puppets.

More and more, C.G. animation is looking to stop-motion and trying to look less like C.G.”

Sam Fell

Mrs. Tweedy (Miranda Richardson) and Dr. Fry (Nick Mohammed)

One reason it took so long was simply that Aardman was busy making other movies. They also wanted to be absolutely sure they had a story that at least matched up to the original, whose big pitch — “The Great Escape . . . with chickens!” — had so impressed DreamWorks founder Steven Spielberg back in the late 90s. “I’ve got sketchbooks somewhere with all kinds of doodles which suggest preposterous sequel storylines that never happened,” says Lord. “Then, about five years ago, Nick and I and [Chicken Run screenwriter] Karey Kirkpatrick happened to be in L.A. for something. We had a chat about it, and that was when we came up with the concept of: This time, they’re breaking in.”

Realizing that the appeal of the original lay in the absurdity of chickens as action heroes, they knew the sequel had to be an action-adventure film. But it also had to feel fresh. At one point during development, it was going to be a father-son story, focused on Rocky (voiced by Shazam! star Zachary Levi) and his and Ginger’s nerdy male offspring. But then the creative team realized they couldn’t sideline their true hero, Ginger (Thandiwe Newton), and smartly pivoted to a daughter character, Molly (voiced by rising star Bella Ramsey), who turns out to be too much like Ginger for her mother’s comfort.

Driven by a desire to explore the world beyond their peaceful island, and frustrated by her mum’s overprotectiveness, Molly winds up trapped in a scarily high-tech farm where chickens are brainwashed into a blissful state — to make their meat more tender — before being processed into a fast-food invention: the nugget. It is this factory farm that Ginger and her plucky team (Rocky, Bunty, Babs, Mac, and Fowler from the original, along with the rats Nick and Fetcher) must infiltrate, to save Molly. But when they discover their old foe Mrs. Tweedy is involved, they realize they must help all of chicken-kind.

Some Babs puppets

The heart of the film is still the hundred-year-old magic trick of making clay come alive. But this film pushed the studio into new places, technically and creatively.

Sam Fell

Molly (Bella Ramsey)

Armed with “some images of chickens being insanely heroic,” says Lord, they pitched this clucking-crazy idea to Netflix. “It went down really, really well,” he smiles. “It was very satisfying.” Fell was also a fan of the “breaking in” concept and didn’t hesitate to come on board as director. “It conjures up connections to Mission: Impossible and the heist movie genre,” he says, while revealing that “Connery-era Bond was a production-design influence.” This is obvious from the sets I find, including the Bond-villain-esque Mrs. Tweedy’s sprawling 60s-style control room, complete with a glass spiral staircase and egg-shaped lanterns.

However, this concept presented a huge challenge for Fell and his team — the biggest, in fact, that Aardman’s ever faced. “The heart of the film is still the hundred-year-old magic trick of making clay come alive,” he says. “But this film pushed the studio into new places, technically and creatively.”

Where the first movie took place almost entirely on a single farm, the sequel transports the chickens to a far larger world. “The studio is literally not big enough to fit an entire Bond movie set,” Fell says. “We’ve had to work in different scales — building miniatures of all different sizes.” More significantly, he had to break new ground, combining traditional stop-motion with cutting-edge C.G.I. to digitally expand these huge settings. “We have virtual production set up for the first time, so C.G. environments are pumped into the studio floor live, through a camera that matches our stop-motion sets,” marvels Fell. “Which to me is kind of mind-blowing. It’s the best way to deliver this Bond villain’s factory farm, full of chickens.” More than 600 chickens, in fact. Far too many for stop-motion to handle, requiring the creation of background-chicken “digi-doubles” using C.G.I., carefully rendered to match the hand-pressed feel of the physical puppets in the foreground.

“Mixing the two together is a complex thing,” says Park. “In some ways, it would probably be easier to go fully C.G.I., given how elaborate and spectacular things are in this film. But at the same time, we wanted to keep the Aardman feel. That’s very much why Sam opted to keep it as stop-motion, so it still has the fingerprints on it and has that tactile feel. That’s what makes Aardman unique.”

Aardman’s individuality shines through every moment of my day at the studio. While the V.R. headset tour of Mrs. Tweedy’s shiny new death factory — replete with ducts, gantries, and conveyor belts — is impressive, nothing is more exciting than getting to hold an actual Ginger puppet in my hands, or looking through drawers full of model parts, with labels that make them sound like they contain witch’s brew ingredients (“Chicken Foot Pads,” “Rat Tails,” “Frizzle Good Hands”).

Both Park and Fell speak of an essential physicality to stop-frame animation, where you can almost sense a connection to the animator who has, as Park says, “breathed life into this clay puppet” through the movements and expressions they’ve applied to it. Though Fell is grateful for the digital technology he’s been able to muster to make this ambitious movie possible, he feels stop-motion can never be replaced. Indeed, he points out, “more and more, C.G. animation is looking to stop-motion and trying to look less like C.G. There’s something about making a beautiful thing, lighting it beautifully, and photographing it through a real piece of glass. It’s ancient technology, but the quality of that image is still stunning.”

Lord, who has been animating clay since he was a teenager in Woking, Surrey, has a slightly different take. “I’m proud of the craft,” he says, while walking me around the studio he founded with David Sproxton almost 50 years ago. “But it’s not the defining thing at all. What should define it is the storytelling. I never think that we do stop-motion films. We just do films.”

See the team behind Chicken Run: Dawn of the Nugget on creating Chicken Island.