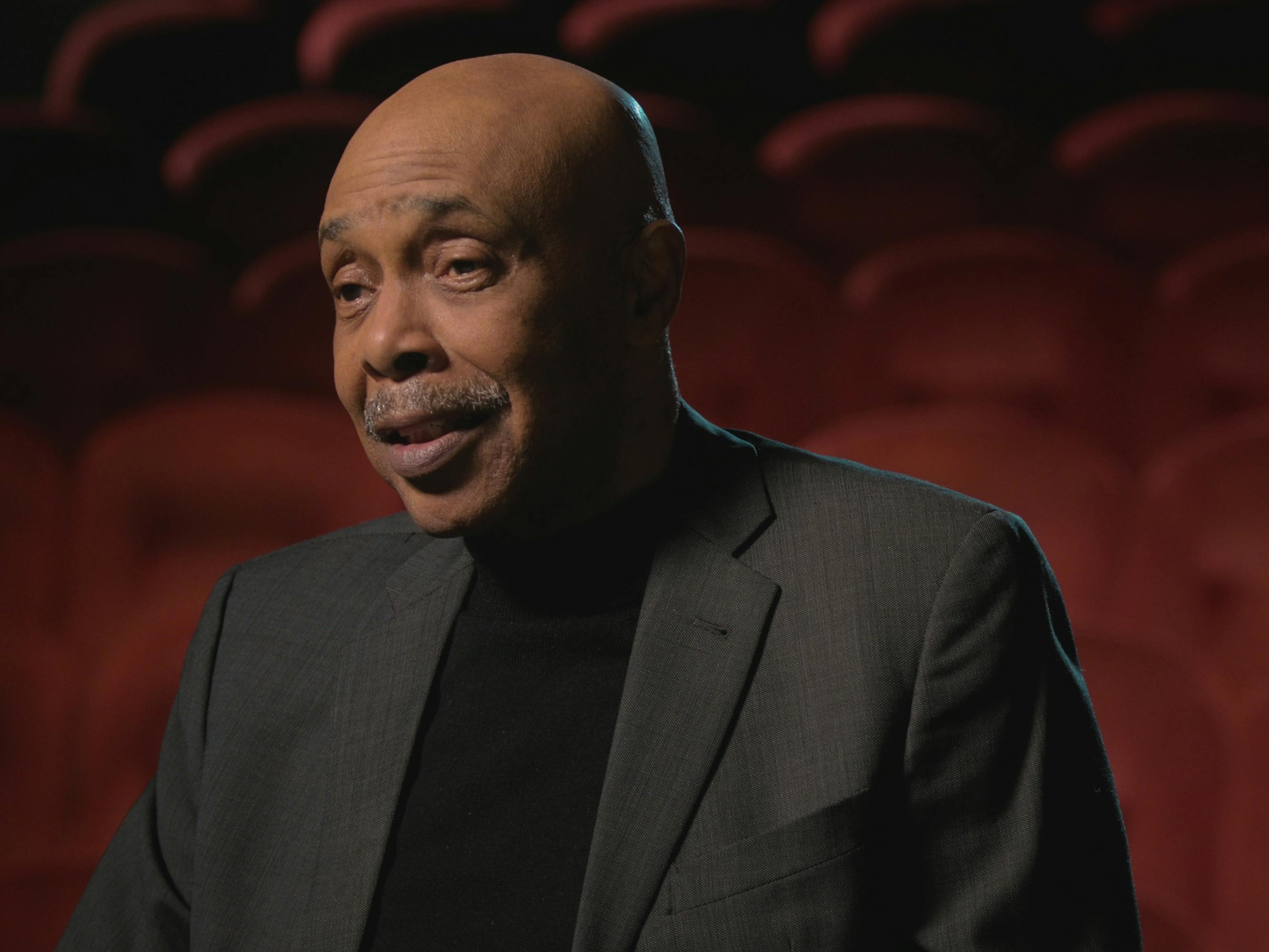

Film critic Elvis Mitchell dissects the rich history of Black film.

History can be unwieldy, filled with twists and turns, shadows and corners. That’s why renowned film critic Elvis Mitchell’s new documentary Is That Black Enough For You?!? makes such a refreshing watch. Chronicling the legacy of Black cinema, with an emphasis on the 1970s Black film renaissance, the documentary traverses the past 100 years to elucidate the Black contribution to Hollywood. It’s not a tidy film because the historical narrative it’s piecing together isn’t tidy — and Mitchell’s movie is all the better for the way it asks questions, opens up dialogues, refuses easy answers, and takes the time to let itself luxuriate in Black art. “I was out to create something that was as much essay [as] documentary,” says Mitchell. “I think I’ve achieved it.”

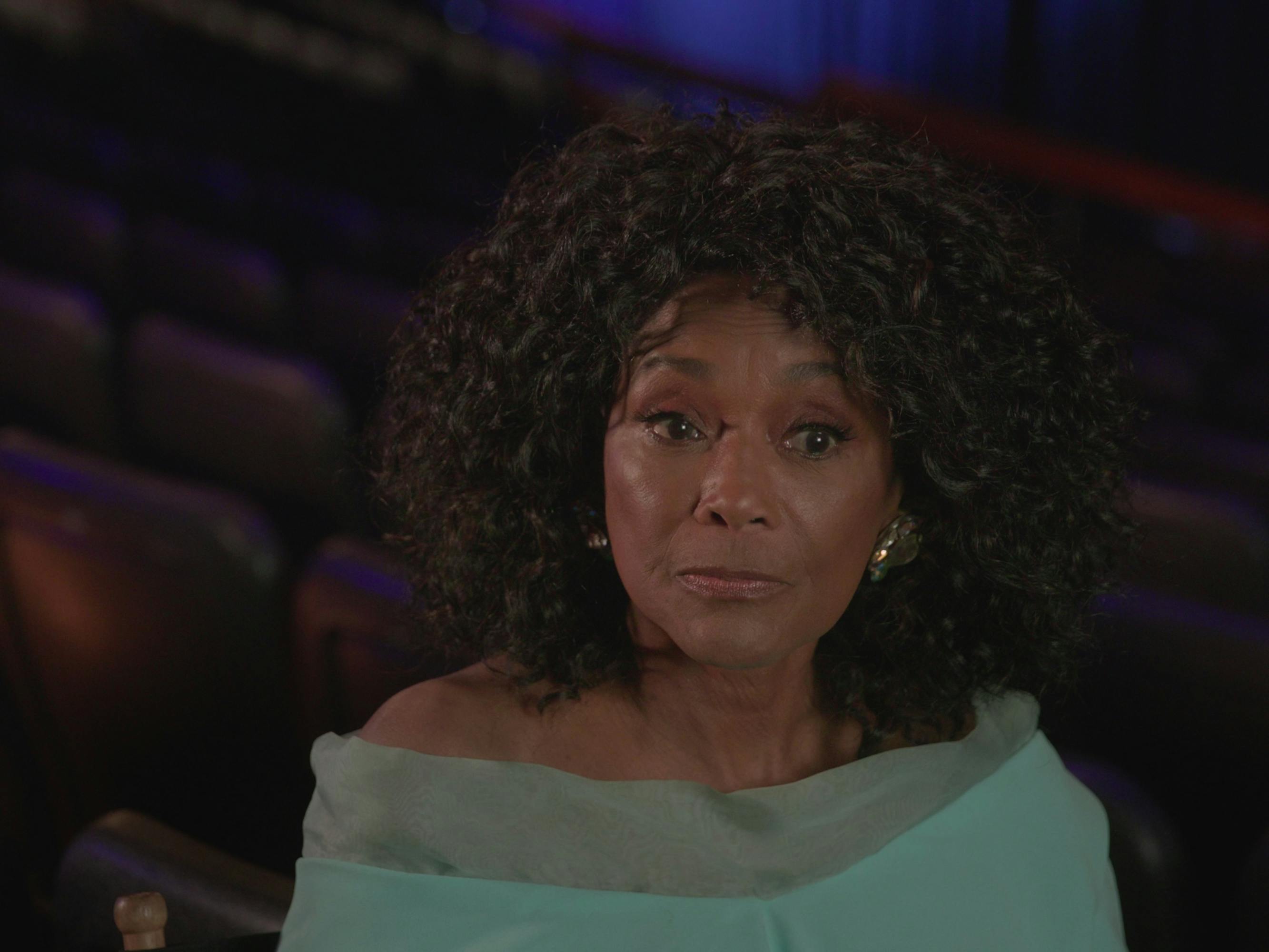

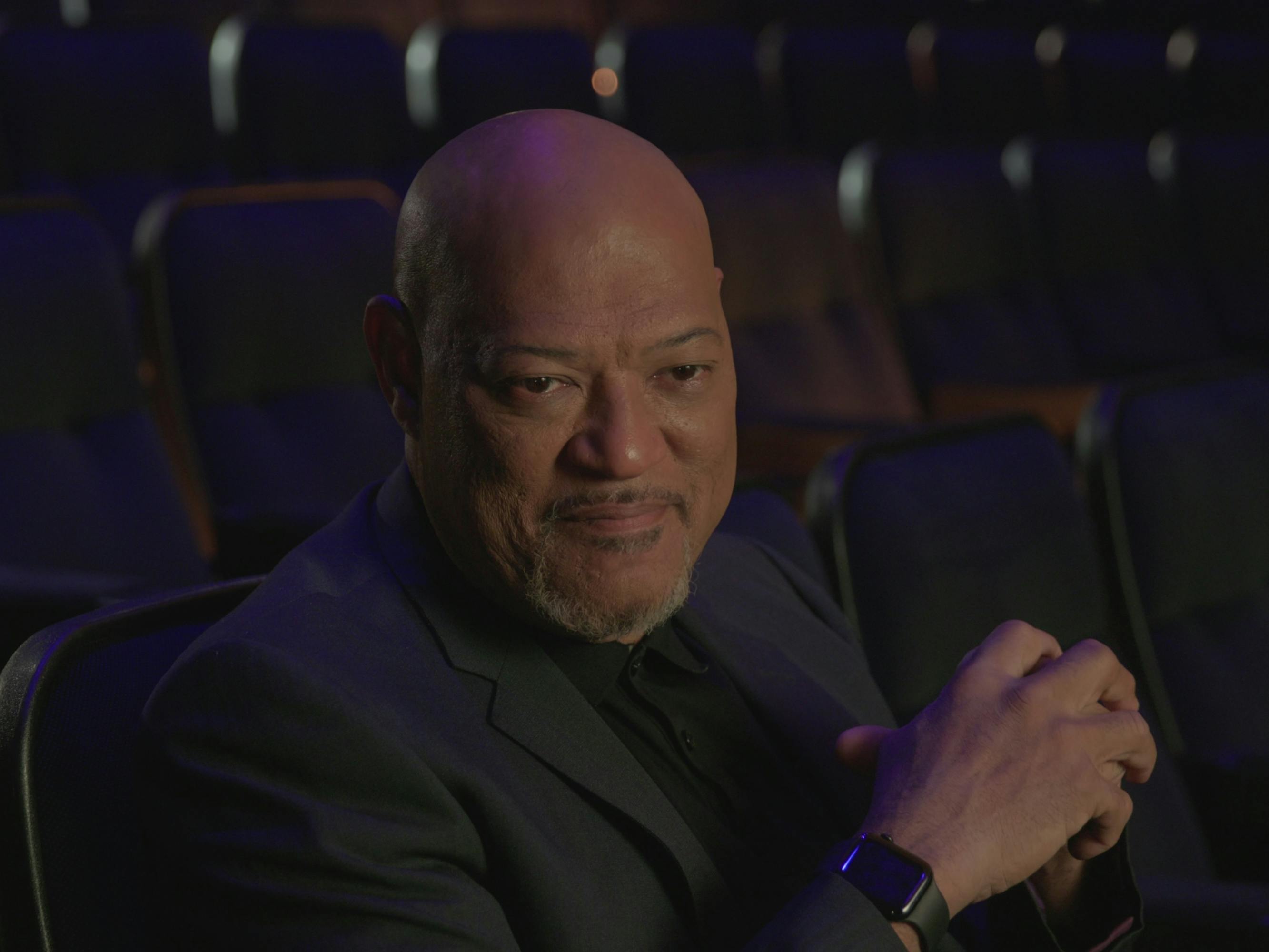

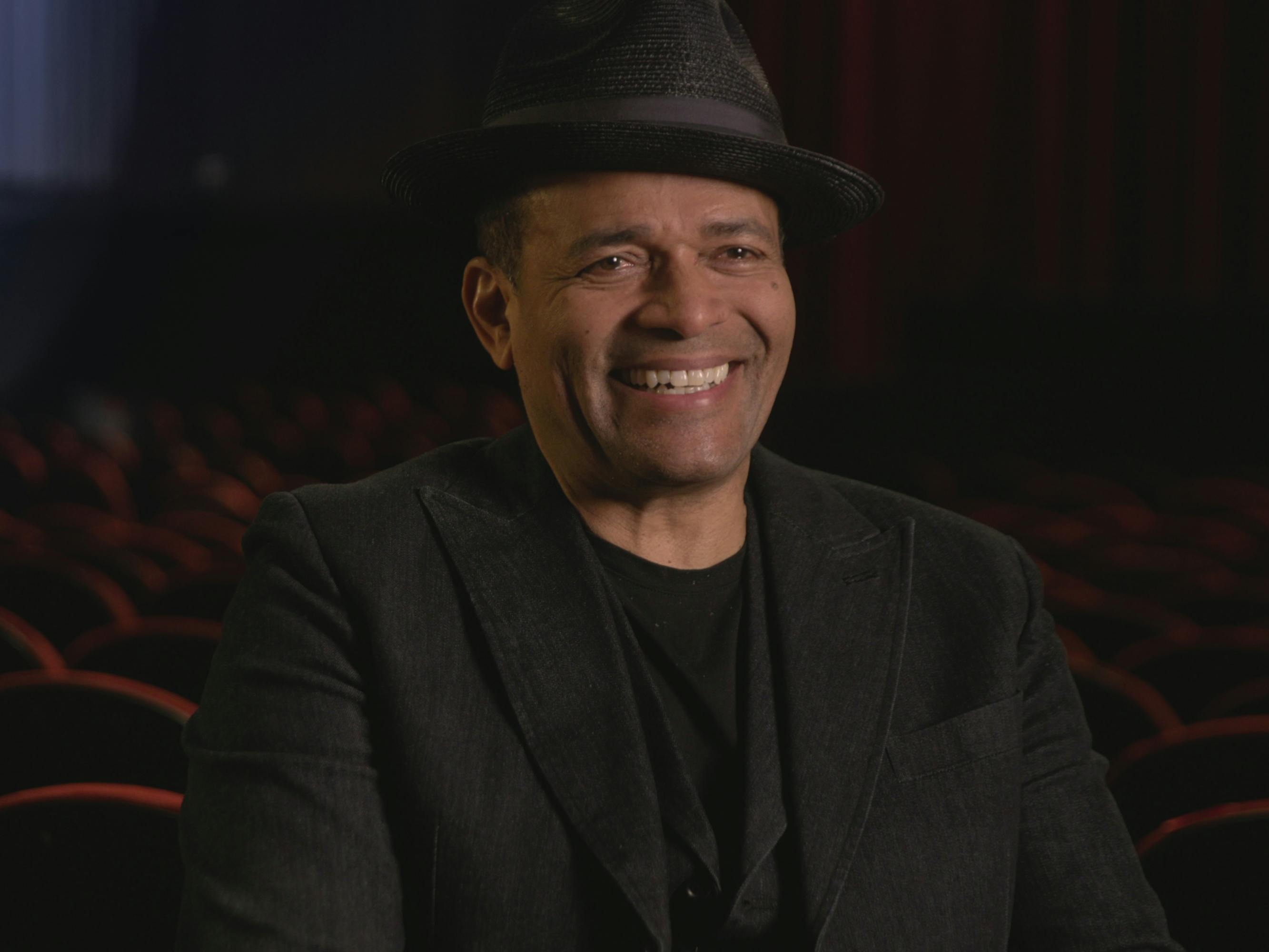

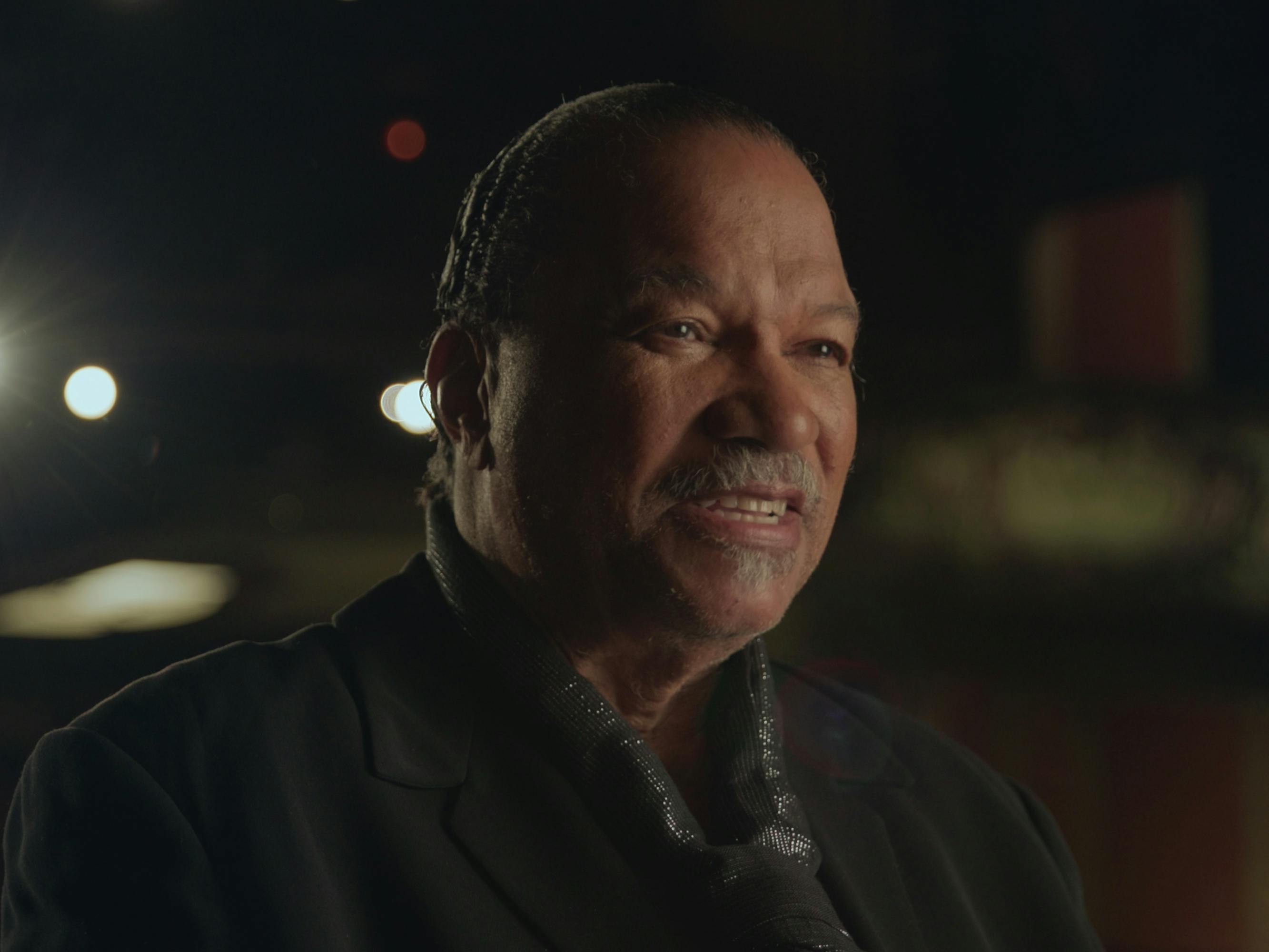

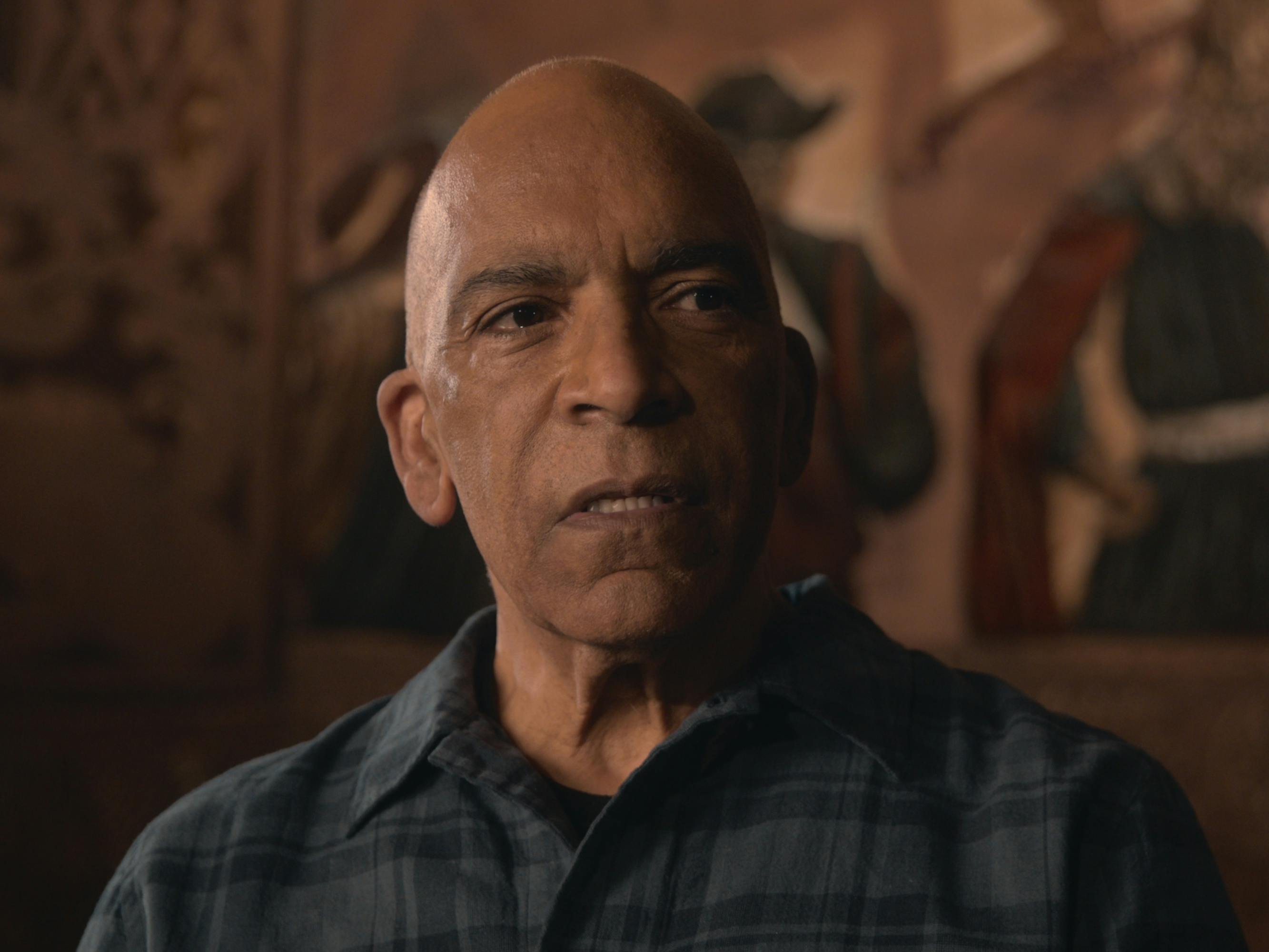

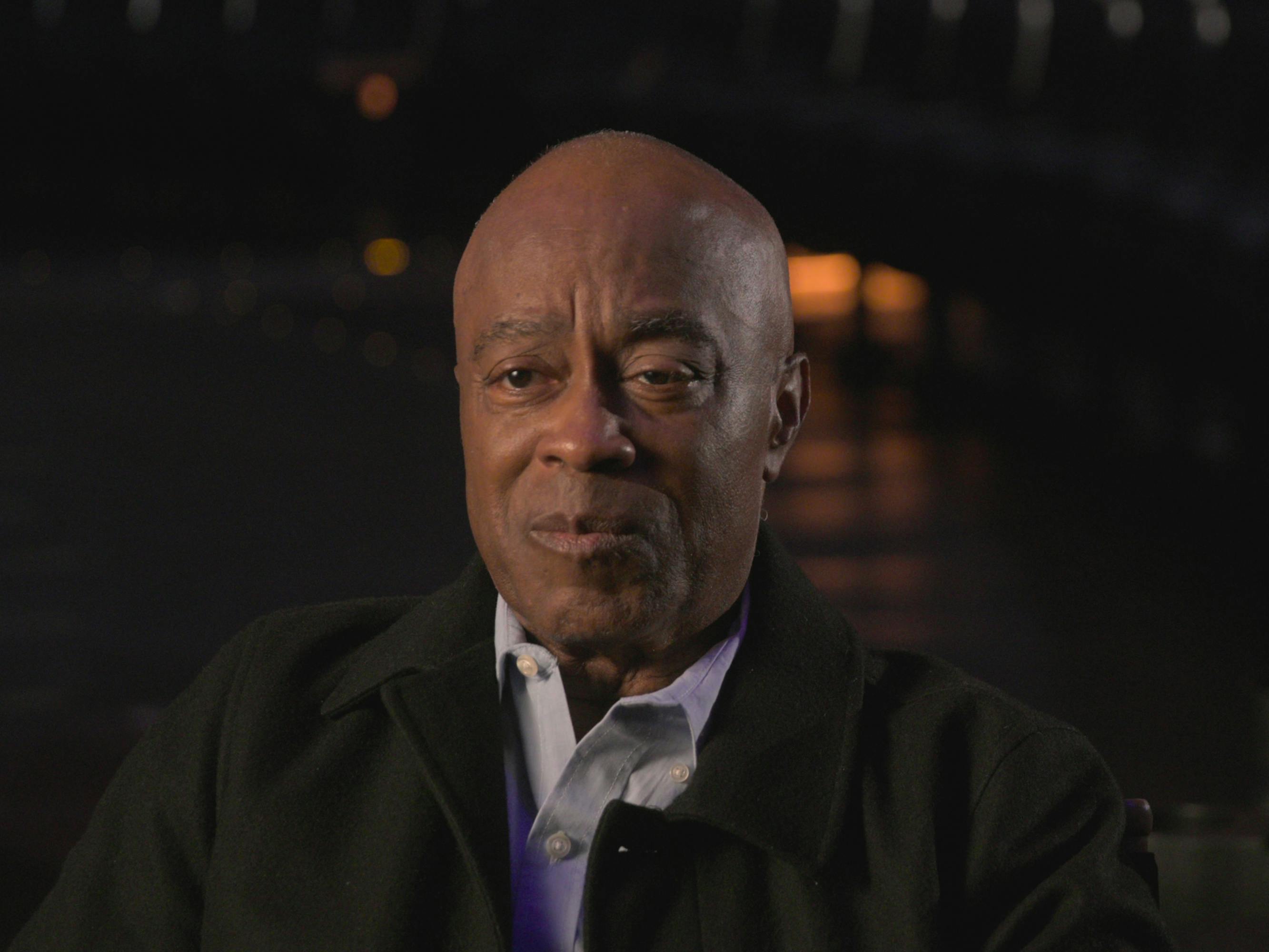

For Is That Black Enough For You?!?, Mitchell rallies a truly all-star cast of talking heads to share testimonies of their formative experiences, lending context to the impact of Black films and characters on Hollywood greats, including Samuel L. Jackson, Zendaya, Billy Dee Williams, Whoopi Goldberg, and none other than Harry Belafonte himself. “Harry, I knew how fiery he was. And Harry’s focus, wit, and level of engagement were astonishing. He was 94 when we filmed him — as present and quick as I wanted him to be,” says Mitchell.

Over the course of the film, Mitchell trains his lens on the systemic racism and lack of representation in Hollywood, as well as the bitter success of early movies like The Birth of a Nation and Gone with the Wind, but he leans more heavily on celebrating the Black achievements. The documentary is incredible at reminding us of classics that have largely been overlooked in the modern mainstream conversation, particularly 1970’s hits like Melvin Van Peebles’s Watermelon Man and Ossie Davis’s landmark Cotton Comes to Harlem.

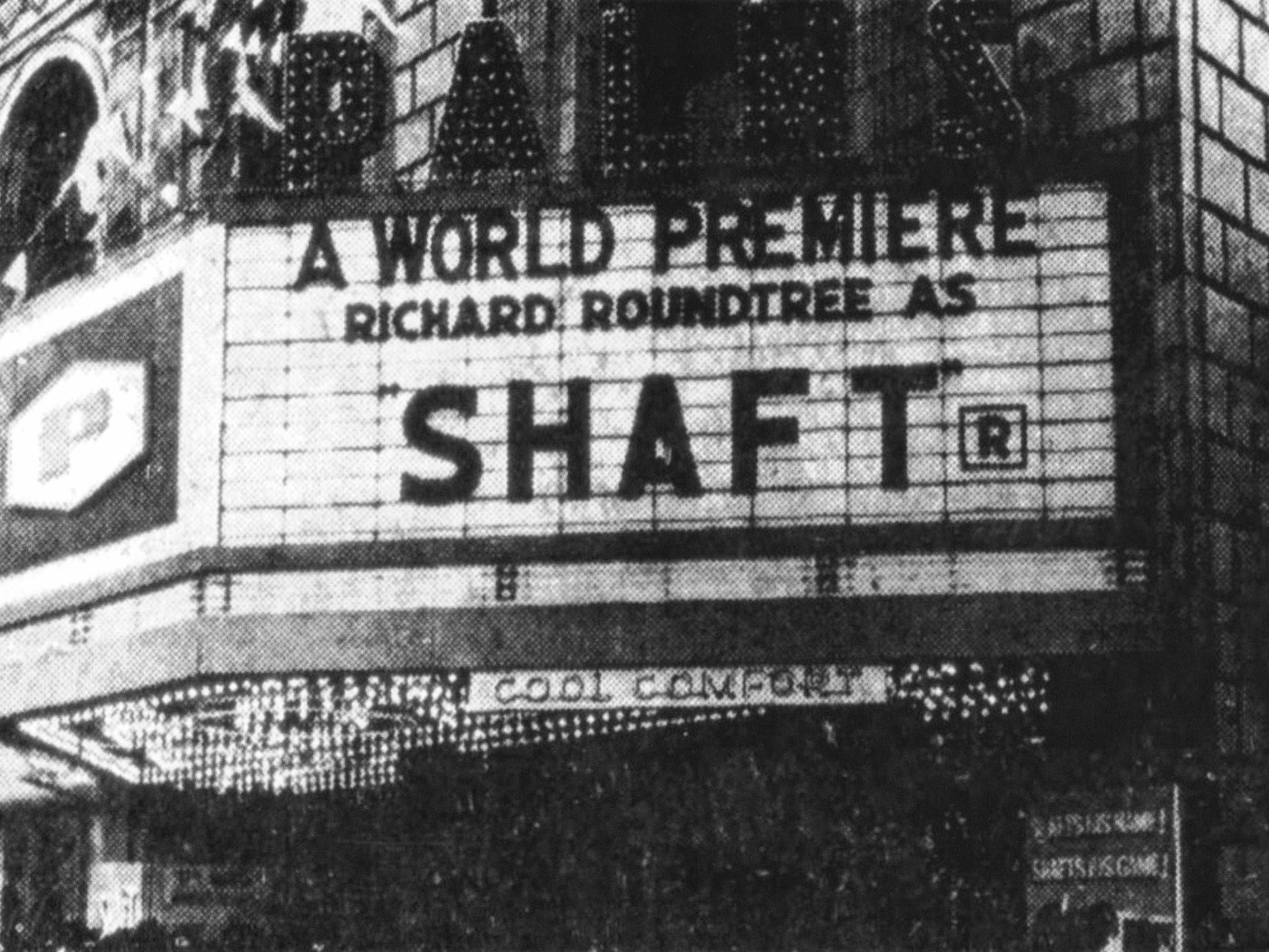

It’s when Mitchell dives fully into the Black film revolution later in the decade, though, that the movie revs up, starting with scenes from Van Peebles’s Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song and Gordon Parks’s earthshaking Shaft in 1971, which Mitchell says would “forever alter the course of movies” and credits for practically jumpstarting the art and culture of the 1970s. “That building up of ambition came from decades of being underused. The groundswell of civil rights, Black cultural ownership, and the rise of Black celebration in other venues — music, popular culture, politics, and sports — finally made their way into the movies,” he says. “I use the impact of Muhammad Ali as a corresponding phenomenon in the film, to demonstrate how his sense of showmanship, married with self-possession, inspired and was reflected in Black film.”

The marquee with Shaft

Is That Black Enough For You?!? showcases Mitchell’s excitement for enormously impactful early Black films that center the realities of Black life and love, as well as his deep admiration for performances by Pam Grier, Richard Pryor, and Jim Brown — and goes beyond the blockbuster Foxy Browns, Super Flys (with that perfect Curtis Mayfield soundtrack), and Shafts of the world to shuffle through incredible clips from Cooley High, Black Gunn, Hell Up in Harlem, Willie Dynamite, and Slaughter’s Big Rip-Off. “I’ve been researching this my whole life,” he says. “There was a lot packed into the film.”

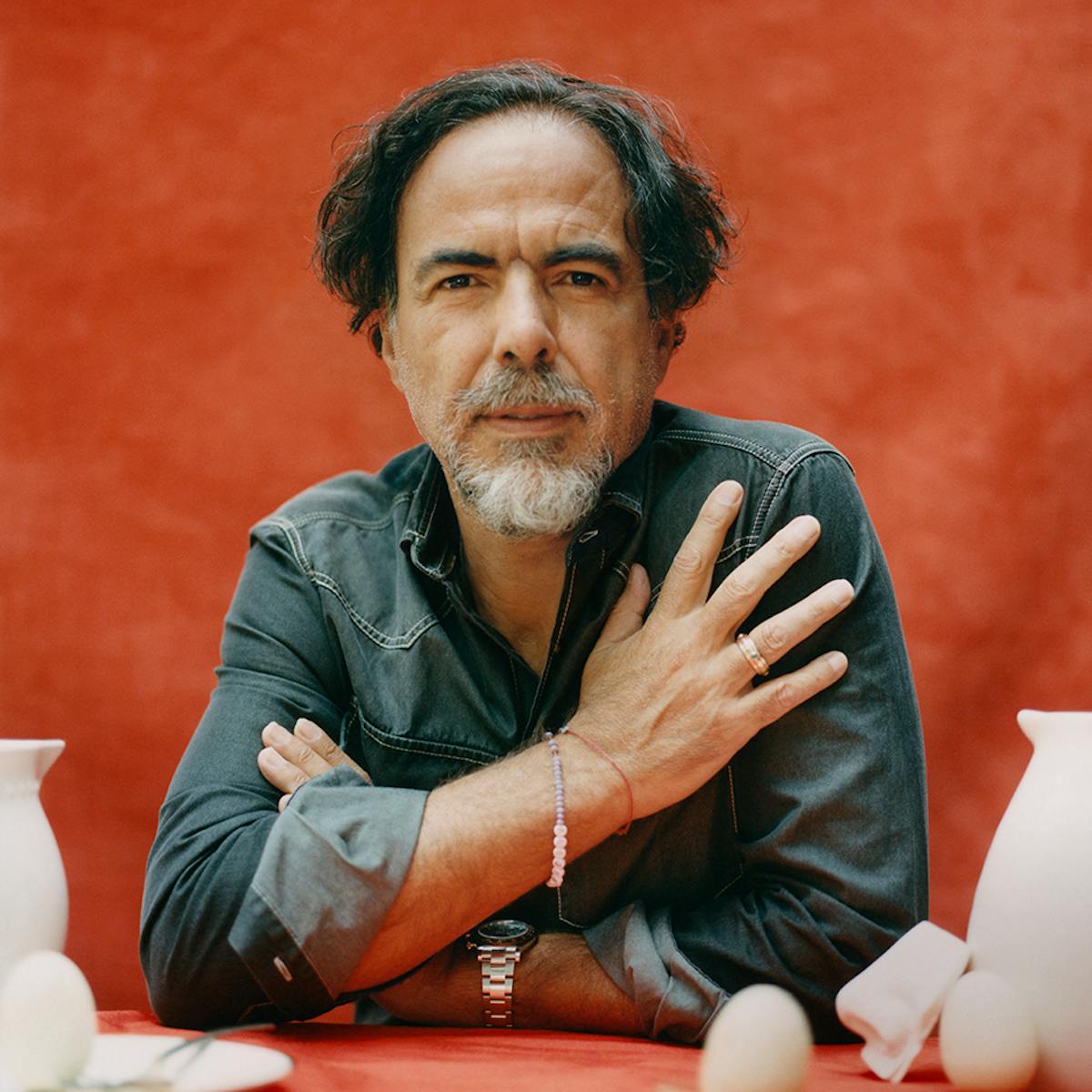

Directed by Mitchell and co-produced by Steven Soderbergh and David Fincher, Is That Black Enough For You?!? is a treat for film nerds and film newbies alike, both a beginner’s guide to Black film as well as a chance for anyone who cares to revel in this expansive cannon.

Somehow, somewhere, Black film will always make its way back to center stage.

Elvis Mitchell

Even with the surplus of magnificent material that’s packed into the film, Mitchell ends on a slightly inconclusive note, with allusions to the 1980s as a retro retread of whiteness in mainstream moviemaking. “I guess it’s ambiguous because this history is still being made,” he says. “There was a fallow period after studios abandoned Black films and audiences until Spike Lee single-handedly revivified film — not just Black film — with She’s Gotta Have It in 1986,” he says. “There’s so much exciting Black talent working now. My fear is that a few consecutive stumbles and that attitude of Well, maybe Black film is done resurfaces because everything is cyclical. But I think the spirit of entrepreneurship is here to stay. Somehow, somewhere, Black film will always make its way back to center stage.”

Or, as we’ve already gleaned from Mitchell’s complex, thought-provoking film, history is a tale of fits and starts, and the revolution, one would hope, is just beginning.