The filmmaker returns to Mexico with Familia, a film about the richness of our closest relationships.

Who better than a Latino to explore the complexities of family bonds? And who better than the son of one the most celebrated authors of all time to dig into what it means to face the memories of our parents?

Colombian and Mexican filmmaker Rodrigo García has spent the past 20 years building a career as a director and writer in the United States. He has thrived in English-language productions, including directing episodes of The Sopranos and Six Feet Under, and has made a name for himself with intimate, well-received films that have attracted such talents as Glenn Close (Albert Nobbs), Ethan Hawke (Raymond & Ray), and Annette Bening (Mother and Child). García admits that, after growing up in Mexico, his move to Los Angeles was possibly an unconscious way to put some distance between himself and the giant he grew up with: his father, Colombian author and Nobel laureate, Gabriel García Márquez.

Familia, García’s first Spanish-language film, represents a return to his origins. Produced by Netflix and filmed in a Mexican town close to the U.S. border, Familia centers on an intense family gathering. In between the food, laughter, and anecdotes, resentment and tension bubbles, as Daniel Giménez Cacho’s (BARDO, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths) Leo and his four adult daughters — played by Ilse Salas (The Good Girls), Cassandra Ciangherotti (Los Espookys), Benny (Ricardo Selmen), and Natalia Solián (Huesera: The Bone Woman) — reunite to decide whether or not to sell the family olive ranch. Together they try to answer the difficult question: How can one part with one’s childhood home?

After the Mexican premiere of the film, we sat down with the director to talk about the various factors that contributed to his return to Mexico, his interest in portraying a different kind of paternity, the memory of his father, and the contradictions that unite all families, no matter what continent they’re from.

An edited version of the conversation follows.

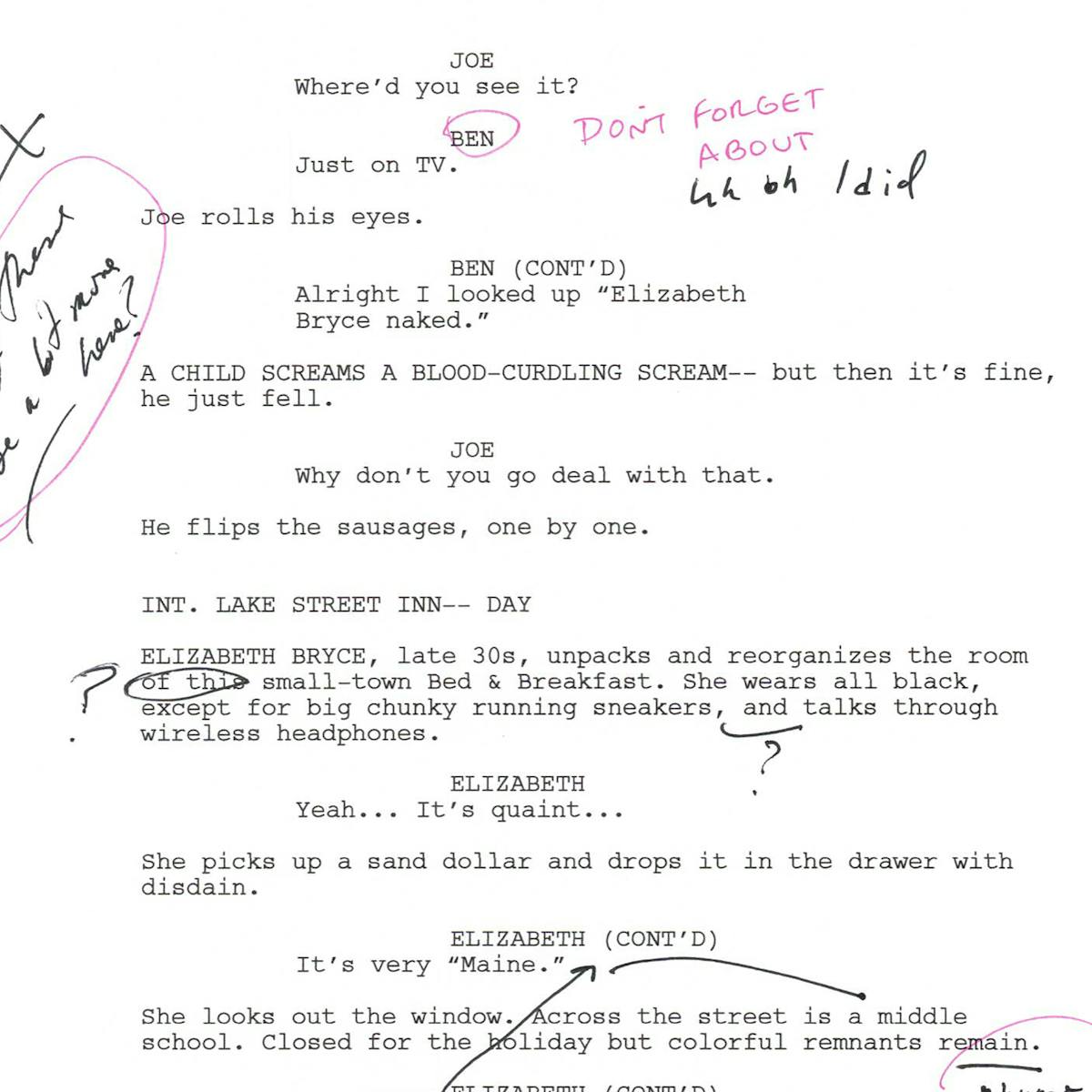

Familia cast and crew

Jessica Oliva: This is your first time directing in Mexico and also your first Spanish-language film. Why did it take you so long to come work here?

Rodrigo García: Honestly, I’ve just had a lot of work that kept me in the U.S. I wanted to do something about Mexicans or Latinos in the United States, but it’s hard. There are 50 million Mexicans and Central Americans over there and it should be easy. But for some reason, there’s a lot of resistance from the streamers and studios. Finally, I just started to get the desire to make it in Mexico, mainly because the theme of family is very well told from the point of view of a Latin family.

Did you write the script in English?

RG: I did originally, but for a Latino family in the U.S. — I wanted to portray a Mexican American family who had an olive ranch in California, exactly like the Mexican version we ended up doing, but over there. But when I couldn’t do it, I said, “Well, this could be my first Mexican movie.” I figured I could adapt the screenplay.

Did the fact that the streamers have expanded the borders of film and television production help your decision?

RG: I think one of the best things about the streamers is that productions are local. I mean, if you make a movie for Netflix, you’re making it for Netflix Latin America or Netflix Mexico. So, I knew Netflix had an entire division dedicated to producing in Mexico. This meant I didn’t have to go to the U.S. or Europe to ask for money for the film. So, I think there was an alignment of interests there that helped get it made well.

As a writer and director, what were the first decisions you made when you moved the story to Mexico?

RG: The first was the script, which I started to translate myself. But I soon realized that, although it was easy to translate it, I was doing it in my Colombian version of Mexican Spanish. That’s when Bárbara Colio, who is a playwright coincidentally from that same border area, was recommended to me. She’s from a town called Tecate, so she understands the dynamics of that geographic triangle composed of Tijuana, Ensenada, and Valle de Guadalupe. And she is well-versed in the idiosyncrasies of that culture, which is very bilingual, binational, and American-influenced. This makes a lot of the families there a lot more liberal, so it isn’t a traditional family from a ranch in the north of Mexico, [who, typically, would be much more conservative], like one from Durango or Chihuahua. It’s a different kind of family.

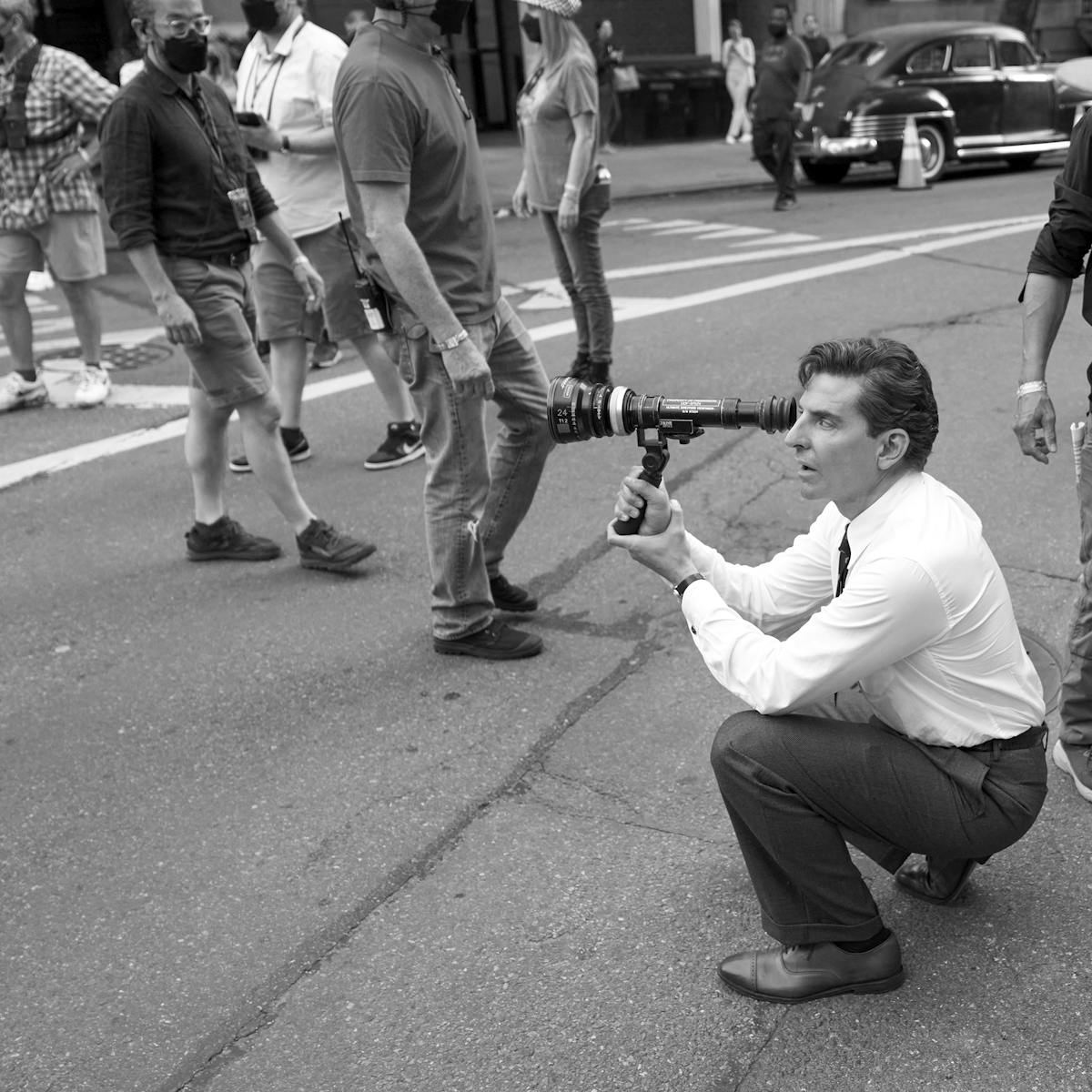

Julia (Cassandra Ciangherotti) and Leo (Daniel Giménez Cacho)

Is it because of Bárbara that you decided to set the movie in that area of the border?

RG: I wanted to set it there, and it was a coincidence that she was from there. But her knowledge was also one of the reasons why I partnered with her. Another reason is that I wanted it to take place on an olive ranch. I think we’ve seen a lot of wineries in movies and television, and they tend to make everything a little more upscale, whereas olives are more about agriculture.

As a Latino, just the title, Familia, puts you in a specific emotional place. How do you think your film fits into the visual imagery of family that is so characteristic of Mexican films?

RG: I don’t think I ever set out to depict the Mexican family. There are an infinite number of types of Mexican families. This is a family that is on the one hand Mexican, but also very much one of a kind. The father comes from a family of ranchers, but he married a writer. That’s two worlds colliding, one of artists and one of land and agriculture. So, I think it’s a family that has the DNA, the same glue and frictions of any family anywhere. There’s a spirit of teamwork, of course. There’s a sense of “we want to work together,” but in the end, there’s also a bit of “I want us to do what I want.” It’s that contradiction.

The coming together of worlds is very clear in the character of Leo, who represents a very modern kind of Latin American father which is not often depicted onscreen. Those men and fathers that had a patriarchal upbringing, but that are surrounded by millennial sons and daughters . . .

RG: It’s what I call patriarchy 2.0. Because he comes from a very conservative background, but he’s always had liberal inclinations, since he married a writer. He has these two tendencies inside. The traditional tendency, which is sometimes dictatorial and, if not controlling, at least manipulative. But he’s also educated by his daughters. I believe daughters educate their fathers a lot. Especially now that we’re living in a very feminist time. I can see it with my own daughters, who correct me all the time and tell me how wrong I am. So, the character is a mixture of the traditional and the modern.

Mariana (Natalia Solián), Benny (Ricardo Selmen), Clara (Maribel Verdú), Leo (Daniel Giménez Cacho), Julia (Cassandra Ciangherotti), and Rebeca (Ilse Salas)

The movie also deals with how we relate to the memories of our parents and how these images of who they were evolve over time. Did making this movie transform the way you relate to the memories of your own parents?

RG: Actually, it was the other way around. The film is inspired by the way I relate to my parents. I even put a lot of my experiences in Leo’s words. I mean, parents continue growing after they die; they become more imposing. You remember them as giants, when, in reality, they were 20 years younger than I am now. They become bigger, and you understand them more. You see them more as humans. The memories influenced the movie, not the other way around.

Aside from Familia, you’ve recently begun to develop and direct a TV series in Latin America. How does it compare to working in the U.S.? What has been different and what similarities have you found?

RG: Neither one is better or worse than the other, but there is a Latin American temperament that I connect to quite a bit. Of course, I’m very assimilated with the U.S., but directing episodes of a TV show called Santa Evita in Argentina, I felt part of it immediately. It was one of the things that convinced me to come to Mexico, because I had felt at home right away even though it was Argentina. I think although the U.S. has incredible technicians and creative teams, in Latin America there is a kind of devotion to the project, a personal commitment.

Speaking of style and genres, after 20 years do you feel you can describe yourself as an auteur? What type of filmmaker would you say you are?

RG: I’m a very stubborn filmmaker who keeps doing his own thing. I mean, I keep coming back to intimate films about relationships, about families. Even if I got offered a movie like Star Trek or some adventure movie, I would have a hard time doing it. I’m very interested in seeing them and enjoying them, but the mere idea of storyboarding for three weeks and then a year and a half of special effects . . . I just don’t have that patience. I always come back to minimalist films. I’ve been lucky to have a long career. I’m still doing my thing and I’ve managed to survive with my stubbornness. The genre I’d like to try my hand at, although I don’t know if I can pull it off, is horror. Maybe I’ll try something in Mexico!