In late 2021, as the world was slowly emerging from the COVID pandemic, musician Jon Batiste sat down with documentary filmmaker Matthew Heineman to discuss the seed of an idea. What if the two created a film about the making of Batiste’s upcoming symphony at Carnegie Hall?

The result is American Symphony, the compelling new documentary that follows Batiste as he sets out to make the most significant work of his career, which he’d envisioned as a classical piece that would blend a multitude of genres. Although staging the ambitious symphony was the initial focus of the film, the shared emotional journey of Batiste and his wife, New York Times best-selling author and Emmy-winning journalist Suleika Jaouad, quickly moved to the forefront. The film is marked by career triumphs and great personal travails: At the outset of his creative voyage, Batiste receives a record 11 Grammy nominations, but he also learns that Jaouad is experiencing a recurrence of leukemia, which had been in remission for 10 years.

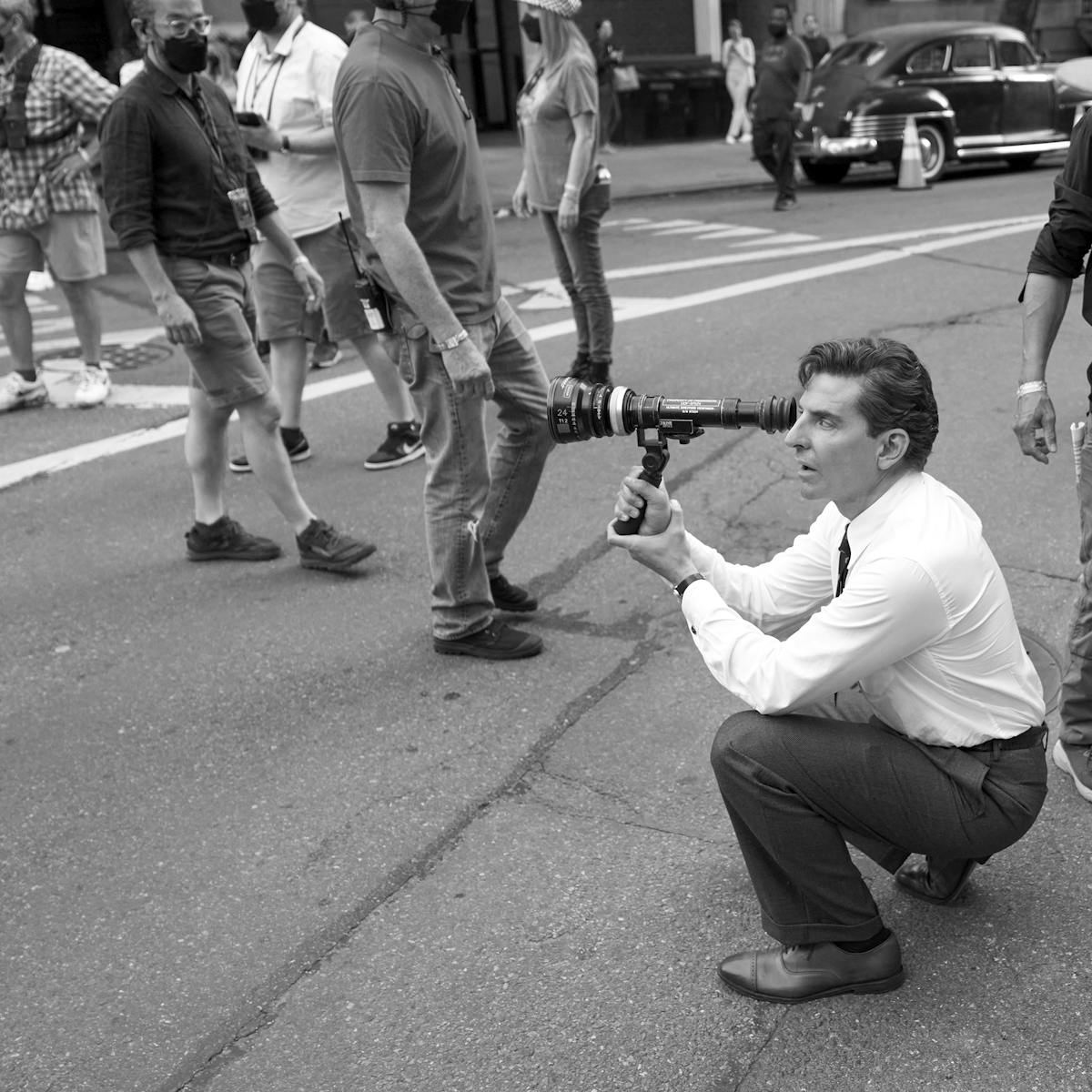

Batiste, Jaouad, and Emmy Award-winner Heineman (Cartel Land, A Private War) recently spoke with Queue to discuss how they approached telling a painfully honest yet sensitive story about art, passion, and persistence in the face of adversity.

An edited version of the conversation follows.

Suleika Jaouad and Jon Batiste

Collier Meyerson: What were the origins of American Symphony? How did the idea for the documentary initially come together?

Jon Batiste: I told Matt Heineman that I wanted to film the making of American Symphony, that I wanted to capture it in a way that was very intimate and unflinchingly honest and not typical of other process or music films. The scale of what I was doing with American Symphony was, in many ways, historic. We started shooting a month after that conversation, funding everything ourselves. That was the beginning. Obviously, a lot happened between that initial conversation and filming that we didn’t plan on.

Suleika Jaouad: It occurred to me that if I were in Matt’s shoes, I would want to not only tell the story of Jon’s actual symphony that premiered at Carnegie Hall, but also the symphony of life that was happening behind closed doors with the news of my cancer recurrence, and starting chemo, and preparing for a second bone marrow transplant. And so, as Matt began filming more of us at home, we had a number of conversations about how and if to involve me and the illness piece of this story. There wasn’t one conversation where I was like, “Yes, let’s do it.” It was a series of conversations about the “why” of telling this other story about what we were going through in our personal lives.

The “why” I arrived at was wanting to show that in-between place: when you’re in the trenches, when you’re surviving day-by-day and you don’t know how your story is going to end — or in my case, the ending is not exactly an ending, it’s ongoing treatment. That felt like a valuable story to put out into the world, and I was willing to do it, but only if we could really do it with the most unvarnished vulnerability and honesty that we could muster.

How did you approach building trust with Jon and Suleika?

Matthew Heineman: Trust is earned, not given. As time progressed, our relationship deepened. My goal with films is not to be a fly on the wall, but to become part of the fabric of the daily lives of the people that I’m filming with. At some point with Jon and Suleika that did happen. And I owe so much to them for having the bravery to allow me in at such an unbelievably critical and sensitive time.

Suleika Jaouad and Jon Batiste

What kinds of conversations did the three of you have about how Suleika’s illness and everything she was going through would be depicted onscreen?

Jaouad: Very early on, I said to Matt, “I am okay with being a part of this film. However, I don’t want my illness to be treated as the dramatic counterpoint to Jon’s success.” Not because I thought Matt would do that, but just because that’s often how illness is treated in books, films, and television. There’s the dramatic phone call, the bump that’s felt, the cleaving diagnosis. And that’s really all I said to Matt in terms of how I wanted the illness piece to be treated.

I was so overjoyed when I watched the first cut and learned that the way that my leukemia was introduced was in the midst of a snowball fight, during a moment of great joy and fun because I think that feels truer to me, in terms of what it means to live with an illness like this.

Heineman: I made this film for many different reasons, but one is that my father battled cancer for most of my life and it’s something that deeply impacted my family. To be able to portray what Suleika and millions of others go through every day was really important to me.

Suleika, given that your writing and art are often from the first-person perspective, what was it like to have the camera turned on you?

Jaouad: It took me a minute to get comfortable with not being fully in control of my own story and allowing it to unfold through someone else’s eyes. Being the sickest you’ve ever been, looking the very worst you’ve ever looked, and feeling the very worst you’ve ever felt is not exactly the kind of state that makes you want to share. But I know from my own seeking out of other stories from that in-between place, how much comfort there is in being able to see someone’s unvarnished reality.

Jon Batiste and Suleika Jaouad

We see a montage of Jon on tour overlaid with voice notes from Suleika in the hospital. The viewer gets a front seat to the whiplash you both must have been feeling, during the best and worst times in your lives.

Jaouad: We had a very conscious conversation about how to handle those couple of weeks, how to stay connected during those stretches of time where we would be apart. From the very beginning of us dating, we’ve always had certain rules. Some of those muscles were already built, but Jon came up with another very creative idea: He composed a lullaby almost every night that I was in the hospital, whether he could physically be there or not. And when he wasn’t, he would send them to me, and I would play them on loop. I think he found a great amount of comfort in composing them. Music is one of his many love languages. And getting to hear that music, to fall asleep to it, was something that brought me a lot of solace.

Batiste: A lot of my anxiety came from the weight of everything, but also just the isolation I was experiencing. Your mind goes into a space where you’re gaming out something that’s not productive for you to even contemplate. That’s when therapy, breathing, and my faith were helpful. Having those moments in the film was also a real act of vulnerability, not knowing how any of it would turn out.

The film explores so many facets of life. Which of its themes resonate most strongly with you?

Jaouad: There are so many takeaways, but I think the one that I’m living — or actively trying to live — is that when the ceiling caves in on you, you can feel pretty powerless and defeated. But rebuilding is a space where you have agency. What I see in the film is a story of what happens when your life is upended, and the many different, unexpected, creative responses you can have.

Heineman: It was certainly one of the hardest edits I’ve ever done because there are so many directions this film could have gone in. There are whole themes and storylines that we didn’t even touch on in the film that are there. But I think once we really started to hone the edit, it became clear that we were making a love story. Among many themes and takeaways from the film, the inspiration to live a life of improvisation [resonates most] because we’re certainly all going to be faced with many hurdles along the way.

Batiste: I believe any art is the property of the viewer. It’s no longer something that I can really dictate. When I make music, I have to think about it like that. You make the song, you make the piece, or you have the performance, and then it’s someone else’s. They live with it. It’s a part of their life. It’s a soundtrack to a moment. It becomes like a friend to them. This film feels like that.