Edward Berger, Albrecht Schuch, James Friend, and Daniel Brühl talk through the challenges and beauty of adapting the literary classic.

It’s 1917, and a group of young German students are enthusiastically drawn to fight along the western front, where they’re quickly confronted with the brutal realities of war. Erich Maria Remarque’s best-selling anti-war novel, All Quiet on the Western Front, was first adapted into an Academy Award-winning film in 1930, but it’s director Edward Berger’s newest take, told in German, that brings the story back home for the very first time. Berger, who grew up in Wolfsburg, wanted to tell this war story from a uniquely German perspective, one that was marked, not by heroism, but by grief and shame. In doing so, he takes the world-renowned tale in a new direction, challenging both viewers and himself as a filmmaker. Through extensive research, complex shoots, and demanding roles, the team behind All Quiet on the Western Front takes us deep inside the trenches of World War I. Felix Kammerer, in his first film role, plays the young soldier, Paul Bäumer, whose innocence and optimism are tested by his time in combat. Award-winning German actor Albrecht Schuch plays Stanislaus “Kat” Katczinsky, Paul’s good friend and a more seasoned comrade on the battlefield.

Berger, Schuch, director of photography James Friend, and actor and executive producer Daniel Brühl joined journalist Francine Stock for a discussion about bringing this timeless story to life.

An edited version of their conversation follows.

Paul Bäumer (Felix Kammerer) and Stanislaus Katczinsky (Albrecht Schuch)

Francine Stock: There have been two previous film adaptations of All Quiet on the Western Front. But this one is from the German perspective, in the German language, for an international audience. Why now?

Edward Berger: Where you’re from always informs how you make a film. I grew up in Germany, watching films of the genre from England or America. I always wondered why, until I realized it’s not only budget-related; it’s also the story that you can tell. In England, you can tell the story of the hero. England defended itself. America liberated Europe from fascism. And that leaves a very different legacy or heritage within the audience, and within the filmmakers of the country. You can suddenly tell a story with a sense of pride and honor, and the hero’s journey.

In Germany, if you grew up there and are telling a story of this kind, there’s nothing to be proud of. There’s no honor. There’s just shame, guilt, and a sense of responsibility about what happened. Ideally, or hopefully, the film feels different in the end. It’s a German film rather than an English film. It has a different perspective and a different feeling and adds to the conversation that we can have about these types of films.

James, you and Edward had a relatively long pre-production period, which allowed for an amazing formalism. There is chaos onscreen, but it is framed by these extraordinary moments of beauty. Was it extensively storyboarded?

James Friend: We shot-listed and storyboarded almost the entire picture. The finished product, if you put it next to the storyboards, is frighteningly similar. We had quite a unique methodology in pre-production where we, purely out of necessity, were basically locked in a hotel suite. Ed would come by every day and we would forensically break the script down. At this stage, we never actually had any sets. We had nothing. There was one point where we didn’t even know what country we were going to shoot in. That enabled us to just go through the scripts line by line. And, with Ed being the principal writer, we had the luxury of saying, How do we want this to unfold for the audience next? and really finding that grammar.

We had our imaginations and a pen and paper, and it was deeply frustrating but also very liberating because we were really encouraged to challenge each other. We were designing shots, but we didn’t have an environment at all. For most of the film, the set is a trench, a muddy corridor, so we could actually go to the production designer, engineer the action, and retrofit the set to what we wanted from the shot. Normally, it’s the other way around: A designer proposes an environment for you to operate in and then you figure the action out.

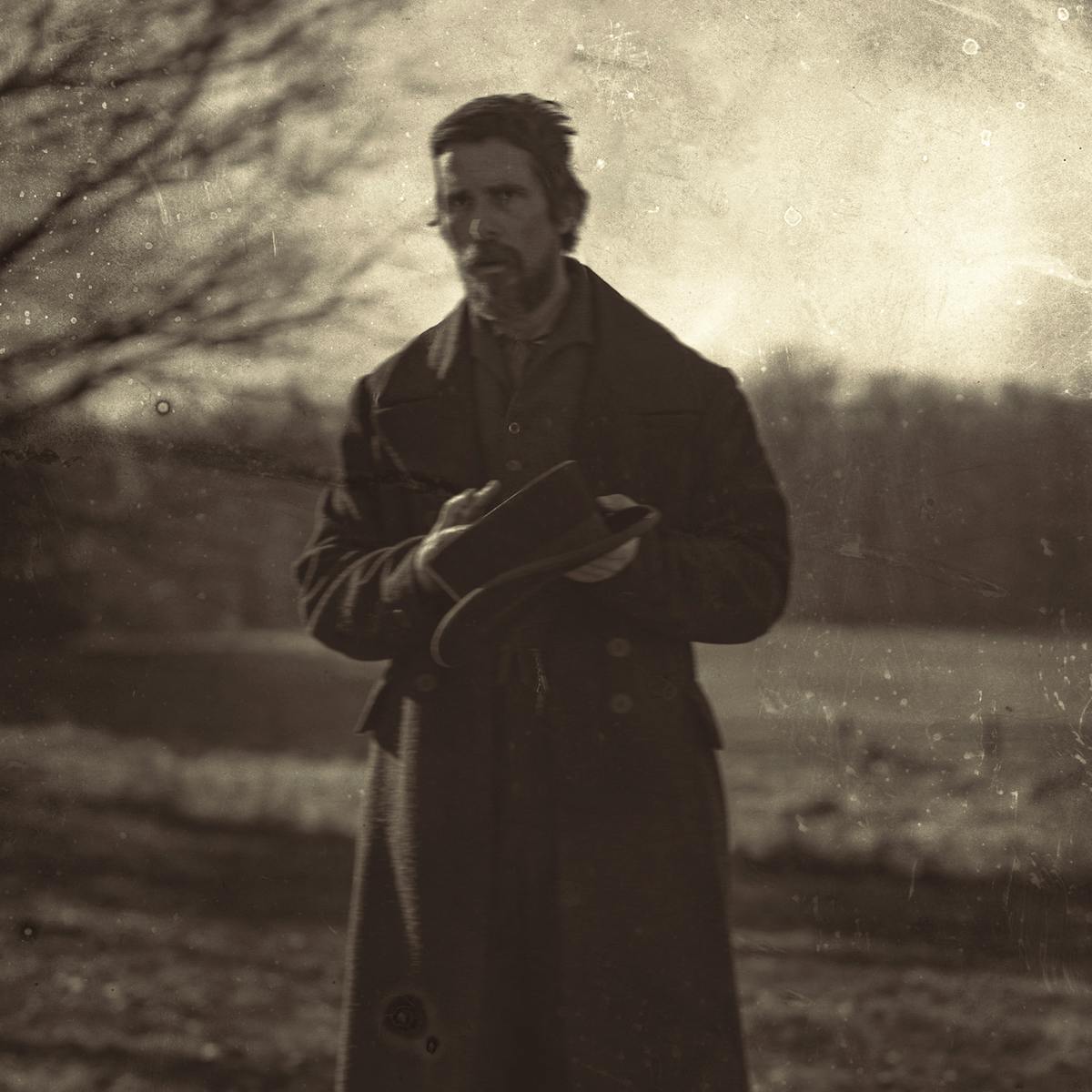

Matthias Erzberger (Daniel Brühl)

Daniel, you’re an executive producer on the film. But let’s also talk a little bit about your character, politician Matthias Erzberger. He’s not in the original novel, so why introduce him in your adaptation?

Daniel Brühl: To start with, it was such an epiphany when Malte Grunert, my partner and friend at Amusement Park Film, the driving force behind this film and the main producer, came across a new script of All Quiet on the Western Front. He called me one day and said, “There’s a new version and it’s quite good because it adds some layers that are not in the book — but it’s written in English and we should do it in German.” This is the most-read book in the history of German literature, and it’s never been done in its original language. With our company, our goal is to always tell stories from Germany that have an international appeal and can travel.

I immediately said yes to playing Matthias Erzberger because I realized that, at least when I was in school, we didn’t learn that much about him. He was such an incredible figure in German history: a Conservative, devoted Catholic from the German province, climbing up the ladder to high politics in Berlin, and he was targeted very early on by the far right for, for example, protesting against the colonial policy of the German Reich. He never got intimidated and he was very persistent, with a very strong moral compass. It was compelling to play someone who, in this whole thing, was the only human voice surrounded by these cold Prussian men who would not stop the madness.

Albrecht, I’m really interested in the character of Kat. Where did you find the inspiration to play him?

Albrecht Schuch: I read a diary my grandmother wrote. She must have been 15 or 16. She would collect all these different sayings from the area she was from. I thought, because some of these sayings were in the book already, they would be perfect for me to bring this personal connection to Kat. There’s this moment after they dig out Paul when Kat shares his bread with him. He stands up and says, “Move, because it brings peace. Don’t just sit there.” I’m always trying to convince myself of the similarities, and also the differences, between the character and myself.

And I loved the silence. I love silence in cinema when I’m in the audience because it gives me the chance to put myself in it, to add my own lines. It’s a unique language without words, but it has so many words. And I love to create all these backstories, for example, with the sayings of my grandmother.