All Quiet on the Western Front director Edward Berger takes us behind the scenes of the German war epic.

When Francis Ford Coppola appeared before the press in Cannes in 1979 to report about Apocalypse Now, he said that the entire team had become increasingly insane as production progressed. He said that it was not a film about Vietnam; it was Vietnam. Again and again, filmmakers speak about their work on war films and say it was as if they were actually at war when filming the movies. They felt like generals who commanded an entire army and went into battle all over again, every day. Films made in a state of emergency can be used to tell about people in a state of emergency.

This is applicable, to a certain extent, to All Quiet on the Western Front, the first German film adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque’s twentieth-century novel, which is still the most widely read piece of German literature worldwide, with up to 40 million copies sold since it first came out in 1929. This latest cinematic take on All Quiet is different from other World War I stories because it takes the perspective not of the winners, but of the losers. There are no triumphs or victories here — at best, we witness brief moments of survival in the face of the war machine. That’s why All Quiet on the Western Front hits you with such force: Its perspective is so human and compassionate.

Another reason is director Edward Berger, who would never call himself a general, though he certainly has a precise vision and great ambition. Berger sees filmmaking as teamwork, as a collective achievement that can only be as strong as the weakest link in the chain. And All Quiet on the Western Front succeeds only because of his leadership and the enormous logistical efforts of his cast and crew to create what is the greatest German film of the last ten years.

Director Edward Berger with actors Felix Kammerer and Albrecht Schuch

Reiner Bajo

All Quiet on the Western Front’s narrative threads are spun by his actors — talented onscreen newcomer Felix Kammerer, as well as Albrecht Schuch, Edin Hasanovic, Aaron Hilmer, Daniel Brühl, and Devid Striesow — and the crafts departments that work on an equal footing with the director. If the cinematographer James Friend, composer Volker Bertelmann, production designer Christian M. Goldbeck, costume designer Lisy Christl, hair and makeup artist Heike Merker, editor Sven Budelmann, and their teams hadn’t surpassed themselves, an exceptional antiwar film like All Quiet on the Western Front would have never come into existence.

Here, director, producer, and screenwriter Berger takes us on a journey through a number of key scenes from his film, providing a fascinating behind-the-scenes look that underscores just how vital the creative team’s contributions were in developing All Quiet on the Western Front into a modern classic that has moved, shaken, and rattled audiences all over the world.

The Reality of War

Edward Berger: We came up with this setting in a hotel suite at the Savoy in Berlin. James, my cameraman, came over and we sat down and storyboarded together. We felt we needed a special shot to open the film where, without skipping a beat, we’re in the trenches with these guys and climbing out with them right into the middle of the battle that’s raging outside. We wanted to experience that live.

The best way to convey this is with a long, uncut take. With that in mind, we started recording the scene. You quickly find yourself confronted with challenges: How do you go about following a soldier out of a trench that is two and a half meters deep in one uniform motion? I looked at James questioningly. He shrugged and said, “We’ll figure it out later!” He trusts his team completely and knew that he would find a solution if his grip and his operator were present. Without the people and artists by my side, I would be lost. Their ideas and skills help me to make the film the way I think is right. Solutions can only be found together.

We rehearsed the setting for three days. First, only with an iPhone, just us, to get a feeling for the requirements. Then camera and grip and the A.D. team came along later, but without actors and extras. Then we coordinated the movements and the process. The day before we started shooting, we rehearsed the scene one last time with the actors and the stunt guys so they knew what we were going to do. You can’t leave anything to chance with such complex settings. All movements and looks must be correct.

We start with a handheld camera in what’s called a stabileye, which moves through the trench to come close to the soldier. When it’s time to leave the trenches, the camera is hung on a techno crane in one flowing movement. It is then detached at the top and taken over by an operator in another stabileye. In order for the crew to have time to carry out these operations, it is necessary to incorporate breaks: Our actor has to wait down in the trenches for another soldier, who climbs up and is immediately hit by a bullet and falls down. We capture that with a pan. That’s what you get when you climb up. Once at the top, the forward movement is momentarily halted because there is an explosion right in front of the actor, causing him to pause. Only then does he start running. All of this contributes to the narrative, but at the same time makes the technical implementation possible.

James thinks a lot in pictures. He has the story in his mind and immediately tries to translate it into images and individual cuts. He had an uncanny film upbringing, so has not only seen every film, it seems to me, but also remembers how they were made. He translates this knowledge into our film, immediately has 1,000 references ready, and is inspired by them. The path from the written word to the imagery is not always easy. If James is involved, I have no worries that we will succeed.

Edward Berger and James Friend

Reiner Bajo

James Friend, Cinematographer:

I can categorically say that Ed is the most talented director I have ever worked with. He’s a genius. Our collaboration together is very special. He most certainly knows how to get what I perceive to be the best out of me. I adore working with him also because I feel like I get the best out of him. I’d say we have one of the most unique working relationships I’ve ever had with a director.

This film was hard to shoot. And it was hard to watch. I think we have succeeded as filmmakers if it is hard to watch. War is horrific. And, at the end of the day, it is an antiwar film because it exposes the reality of war and how [many] go in with a naïve attitude like those poor kids did because they are being seduced by their government, and their country, and their elders. There is a saying from a different film: “War is old men talking and young men dying.” I remember saying that to Ed. That is something that always resonated with me.

The Sound of War

Berger: I showed the film to Volker [Bertelmann] completely without music and told him that I think the music in All Quiet on the Western Front had to have three things: First, I would like to have a sound that is new, which I haven’t experienced yet, and which takes the film to another level. Music strongly influences viewers’ perception and can control their emotional access. It should be intense and unlike anything we’ve ever heard. Secondly, the music should break the images, go against them, destroy them; don’t sugarcoat anything. Third, he should find a soundtrack for the feeling that Paul Bäumer has in his stomach. Volker sent me the music for this scene. I listened to it and knew immediately: This is what I want, what I had imagined. The images soberly capture the war machine. World War I was the first war that was downright industrialized and also bureaucratized; dying is an act of bureaucracy. Finding a sound for that was important. Volker understood it immediately. I always call these three chords the Led Zeppelin sound. The whole soundtrack is based on them. They sound very modern, but they were recorded on a 100-year-old instrument: a harmonium that Volker inherited from his grandmother. You pump air in with your knees, and that’s how you hear the machinery of this instrument. It cracks and creaks. That was perfect. That’s the sound.

I always called these three chords the Led Zeppelin sound.

Edward Berger

Volker Bertelmann, Composer:

Edward and I basically agree that music shouldn’t overwhelm the movie to create any reworked emotions. There are movies that tolerate incredibly emotional music. Especially in classical cinema, you often find that the music accompanies the action one-to-one. In modern movies, I get the impression that people increasingly enjoy not always hearing all the information at the same time. It’s an overload — constant music, constant action, constant noise. We had to think about how to avoid pathos with this piece. We always wanted to stick closely to the protagonist’s story, highlighting the desperation and futility of a situation that he got himself into. He left with enthusiasm, almost as if going to camp, and now finds himself in a war mill that churns through human lives. In our case, this is the First World War, but it is, of course, seamlessly transferable to today’s armed conflicts; it is something relevant and explosive, absolutely current. You have to be careful with where you place the music, but also with what it should serve exactly. You have to look the story in the eye and ask yourself how you can bring it closer to the viewers who are seeing it impartially.

The Dirt of War

Berger: In this scene, Paul lies buried under the ground in the bunker and is then dug out. Felix Kammerer was really lying under the ground. We had dug a hole where we could shoot parallel with the camera. He must be freed, uncovered. A corpse is lying on his stomach next to him, with a distinct wound in the back of his head, which Paul only sees out of the corner of his eye. You actually only see one of Paul’s eyes in the dark, which is accentuated by the fact that his face is covered in black dirt — wonderful work by make-up artist Heike Merker. You get a little nervous when you don’t recognize the main character: It was one of the first days of shooting, and he comes out and you only see his eyes, everything else is covered in dirt. Of course, Heike always has to maintain continuity. In the beginning, the make-up is clay. It then gets smeared with real mud, because there’s no other way when it’s under the ground. We started with a lot less, then the earth fell on him and he became pitch black. Heike looked at it and said: “Oh, that’s how it is . . . that’s all right!” She could work with that.

Heike Merker, Makeup and hair artist:

The preparation was very intensive, with a lot of research to find suitable materials, the right tone, and colors. How to tell the story was important for Edward, which look it should have and which not. Working with Edward was an incredible collaboration; he is always in open dialogue and exchange with all departments. Sometimes, it was too warm and sunny, there was never enough time, the light was unpredictable, and it was difficult to move in the mud. Suddenly there was rain, a storm, or it was too cold. Another explosion, again and again until it was no longer possible. The film was not like others and, in every respect, a challenge, but also a great pleasure.

Albrect Schuch, Moritz Klaus, Felix Kammerer, Aaron Hilmer, Adrian Grünewald, and Edin Hasanovic.

Berger: Of course, this also goes for the costume. As you can imagine, we didn’t just have one costume for the main character, but several uniforms in various stages of tattering. At first it is in perfect condition, innocent. You can’t get this costume dirty either, because we might need it in this immaculate condition. Then another costume arrives, which is beginning to wear out, sometime around the time the bunker collapses. A time jump follows. Paul has been at the front for a year and a half. The uniform is worn, damaged. And at the end there is another version where the uniform is almost in tatters. We had several dressers and textile artists who spent several weeks shredding hundreds of costumes with graters and other tools. If we wanted to suggest winter, we processed the costumes accordingly, icing them at the collar so that the freezing cold would come across. We applied very pale make-up to Albrecht Schuch, accentuating the tip of the nose and the ears in red, and, of course, ice — in the beard, in the eyebrows, in the hair. You have to feel the cold. It must creep up. All of this can only be achieved through the interaction of different departments.

Lisy Christl, Costume designer:

At one of the first meetings I had with Edward Berger, we talked about how creative you can be with the costumes in a historical piece like this. Yes, the uniforms are predefined, but these uniforms contain very different characters, and you have to define their personalities very carefully. You always have the opportunity to see what’s underneath or inside — less when you are on the battlefield, but more in the moments in between. In order to be able to paint these characters convincingly, it was important to me to research their prewar lives, how they learned to survive under these severe circumstances. This is then also reflected in their uniforms. Perhaps, before this movie, I would have shrugged and said, “Well, it’s simply a uniform movie, there are few possibilities when designing your costumes.” Now, however, I would say the opposite. I actually thoroughly enjoyed exploiting my little leeway. If you have little opportunity to illustrate your characters, you just have to be even more precise and specific.

Berger: We planned the installation of the trenches meticulously in advance. I worked with James Friend to determine what we would need. Every meter of this labyrinth is used in the film. We measured the lengths precisely, every bend and junction, every shelter, every indentation. Our production designer Christian Goldbeck then created and implemented it congenially. We shot in a large area just outside of Prague. There we noticed right away how brown the earth is. In the Czech Republic it is like in Berlin, primarily Bohemian sand. This doesn’t look good. It suggests heat and desert instead of cold and ice. So we brought in extra dark soil to make it look black and burned. The impression then continues on the battlefield in front of the trenches. We created bomb craters and partially filled them with water to increase the effect.

Christian M. Goldbeck, Production designer:

In our very first conversation, Edward and I noticed that war events in historical movies were always depicted as gruesome, but almost always from the victor’s point of view, resulting in stories about heroes. The novel All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque is definitely not a story of heroes. Our concern was to represent the steady fall and the ordeal of our protagonist Paul, as immediately as possible, to experience it as closely and realistically as possible without exaggeration. It’s not only about seeing the set, the scene — you should be able to smell it. In order to determine exactly how many meters we actually need in order to do justice to the plot and action, we measured it using a stopwatch. What does the maze of trenches look like? It was like a puzzle that we had been trying to put together for two months at the drawing board, circling it scene by scene to find out what was absolutely essential.

War Against War

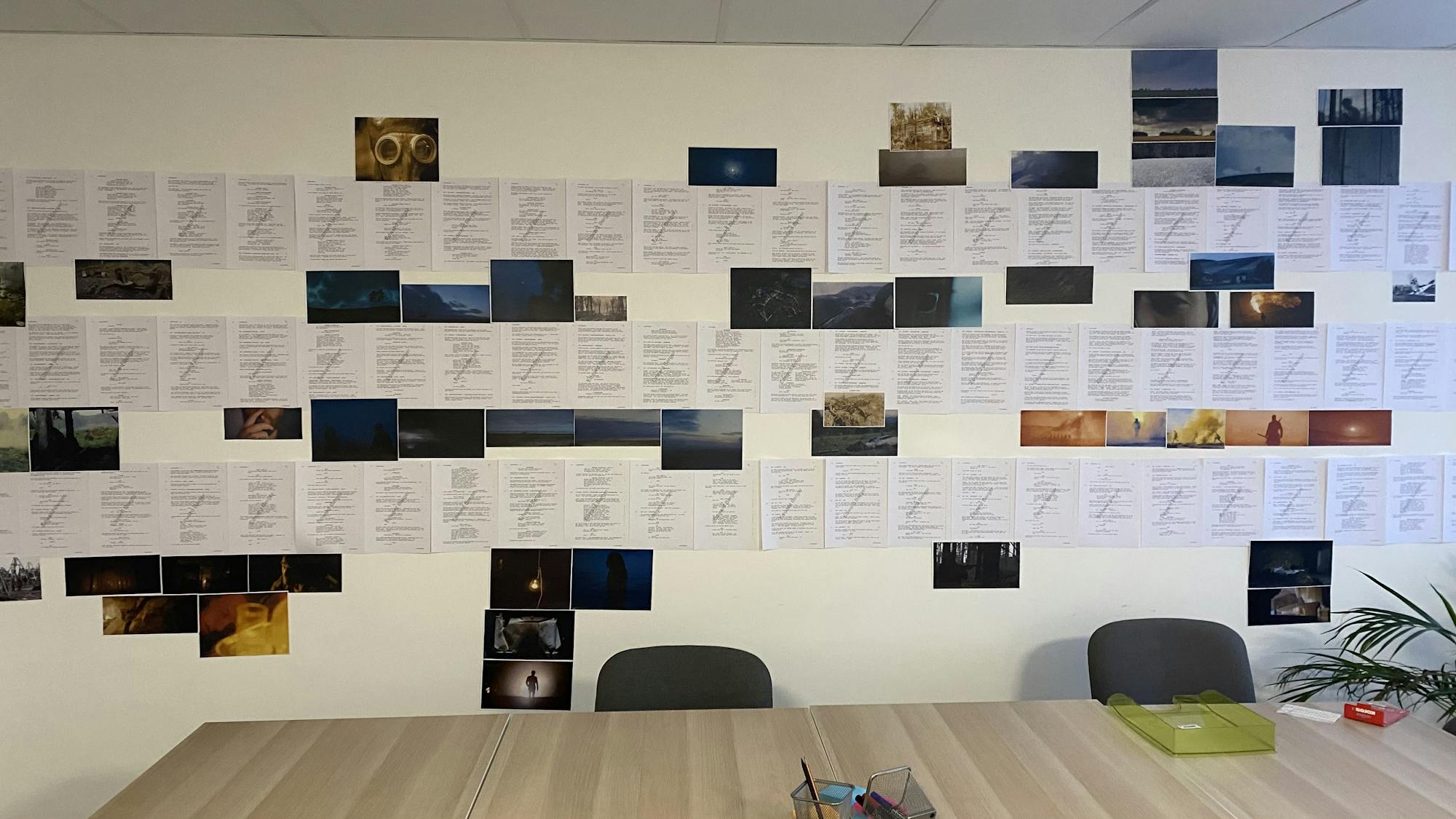

Berger: The scene takes place early in the morning; it is freezing cold morning frost. The actors are back in their frozen costumes. A roaring sound announces the tanks (built by production design), emerging from a yellow haze (courtesy of the S.F.X. department). Very precise editing is necessary in order to make this scene really work. That certainly applies to all scenes in the film, but here Sven Budelmann’s editing plays a very special role. It is remarkable that every single edit was already created in the storyboards. Everything was planned exactly. That’s how we shot it, and that’s how we cut it. The interplay of pre-planning and editing is extremely important. This also applies to the other departments. Everyone must know exactly what is required of them. The tank scene is immensely complex. People fly in the air, it rains sand and dirt down on the figures, the tank has to drive over the trenches, which of course it can’t do in real life, it would collapse. We filmed those moments on a separate section of the trench.

A tank rolls over the ditch and Paul shoots up. You can’t shoot that live, it has to be realized in separate elements. We had a section of the trench that was enhanced by the set design team so the tank could actually drive over it and not just collapse. This was the only way the cameraman could actually stand underneath. The sequence of cuts in this scene is sometimes rapid, no shot is longer than two or three seconds. They weren’t filmed much longer either. Of course, it still needed some fine tuning, sometimes a frame more or less really matters. But basically, Sven was able to simply assemble the filmed material based on the storyboards, and it came very close to the desired effect of the scene. We always knew exactly what to shoot. For that scene, it was important to find a cinematic way to create the greatest horror for the soldiers. We used the camera to suggest that we were under the tank and looking up. That means: There is a pan in which the tank drives over us. At that moment, we rain down a whole wall of dirt on Felix, and the camera vibrates like the whole floor. In a close-up, we cut to Aaron Hilmer, who is screaming like crazy. In reality, there is no tank far and wide. But the sequence of cuts suggests that the tank rolls right past him. There was also a P.O.V. of a tank crushing and crunching two young soldiers. We don’t show this as an end in itself. We just want to make clear what’s at stake for our boys, how great the horror is they’re helplessly facing.

Edward Berger's office wall.

Sven Budelmann, Editor:

For the director, the start of editing is tough. While I’ve been able to get used to it for months and am already familiar with this world, he has to jump right in and get himself up to speed as quickly as possible. You want to work on an equal footing. I already know what it feels like when our main character is seen for ten seconds longer in the long shots instead of ten seconds in close-up. These are the processes that the director has to find their way in. It is important to give him the necessary time and perhaps also allow him to try out things that you have already tried out and discarded yourself. For me, this was an interesting moment because I was forced to put myself in Edward’s shoes, almost like a second perspective, an exciting way to correct your own work and very good for the movie. We really left no stone unturned, tweaking everything again to find the optimal solution. There is a quote, War is like a game of chess. I think you can apply it to our editing process too.

For more on the making of All Quiet on the Western Front, watch the special behind-the-scenes video here.