The on- and offscreen creatives behind Maestro celebrate the film at the New York Philharmonic.

On a bone-chilling Valentine’s Day in New York City, Bradley Cooper presented a brand new way of experiencing Maestro. Some six months after debuting the drama that he co-wrote, directed, produced, and starred in, a film that garnered seven Academy Awards nominations, Cooper welcomed a packed house to the David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center for a one-night-only mixed-media experience with the New York Philharmonic titled “Orchestrating Maestro: Music and Conversation.”

“What you’re about to see is an experiment,” Cooper, sporting a stylish tuxedo, remarked during the introduction. “You’re listening to the music, but in your mind, you’re experiencing the story.” The Philharmonic orchestra performed live renditions of selections and compositions by Leonard Bernstein, the man at the heart of Cooper’s Maestro, interspersed with audio and video clips from the movie itself. The event was the talk of the town. Even before stepping onto the famed plaza, one could overhear an attendee buzzing, “Will Bradley Cooper be conducting it himself?” while ascending the iconic Lincoln Center steps. But while Cooper was clearly at the helm of this “experiment,” the task of actually leading the Philharmonic went to Yannick Nézet-Séguin, the music director of the Metropolitan Opera and the music and artistic director of the Philadelphia Orchestra, who also served as a conducting consultant on the film, coaching Cooper during his extensive training to take on the role of the famed conductor and composer.

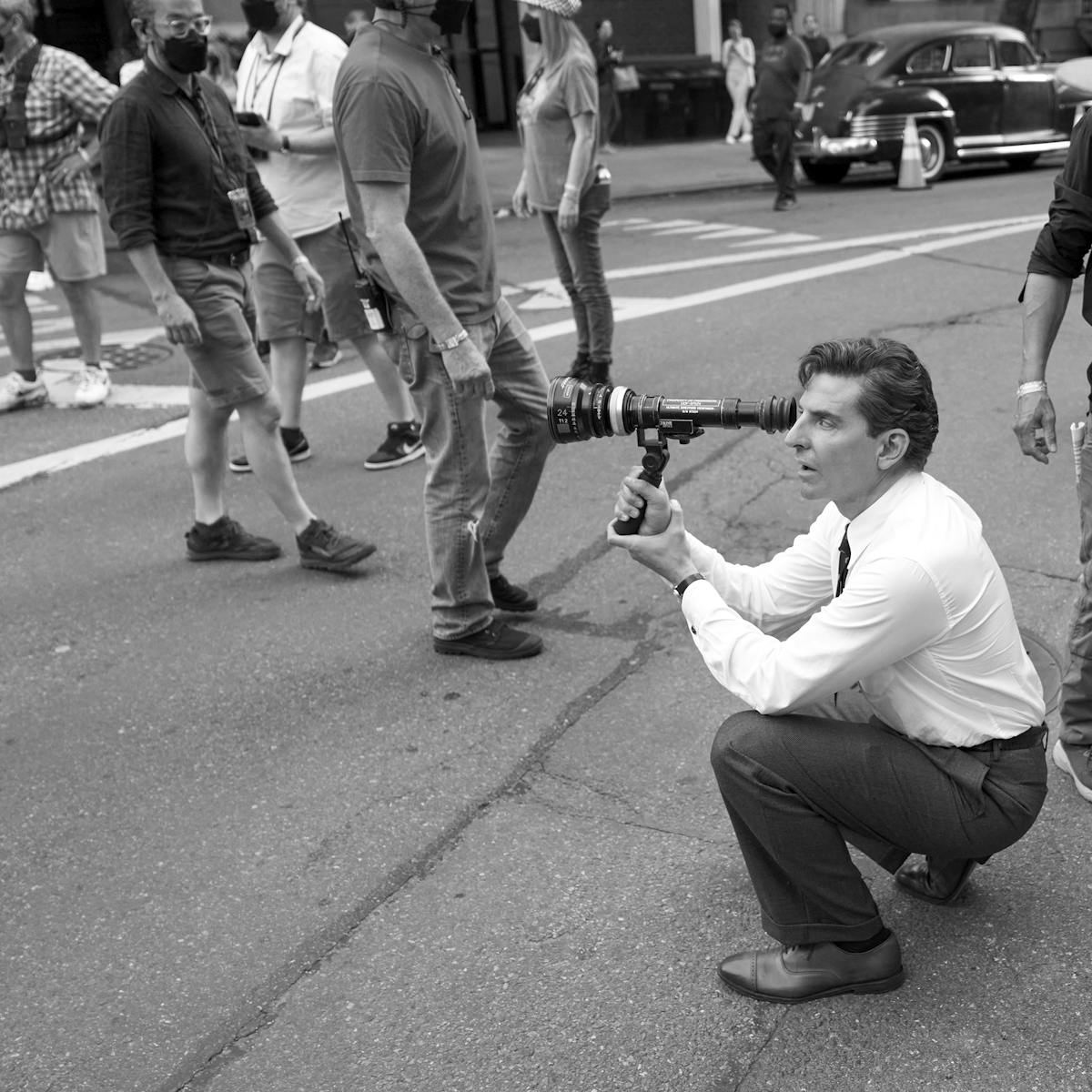

The show opened with audio from the film’s pivotal opening scene when, on November 14, 1943, Bernstein receives the call asking him to fill in for Bruno Walter and subsequently makes his debut at the New York Philharmonic’s conductor’s stand. The shrill ringing telephone and a bit of dialogue played over the speakers. “No chance for rehearsal?” Cooper asks as Bernstein, inspiring laughs from the live audience — which included such notable names as Spike Lee, Anna Wintour, Ellen Burstyn, Sam Smith, and Candice Bergen — as the orchestra took up their instruments in real-time. Also in the audience were some of the film’s crafts team and producers including Matthew Libatique, the film’s cinematographer, prosthetic makeup designer Kazu Hiro, sound designers Jason Ruder and Steven Morrow, production designer Kevin Thompson, and producers Fred Berner and Amy Durning.

From then on, it was unmitigated, euphoric joy to hear and see Bernstein’s range as an artist unfurl, with the Philharmonic blazing through a selection of works that reached from pop classical, like his score for West Side Story, to the ecstatic drama of Adagietto, a sublime and romantic movement that Bernstein particularly adored from Gustav Mahler’s masterpiece Symphony no. 5.

Co-star Carey Mulligan — who plays Felicia Montealegre Cohn Bernstein, actor, artist, activist, and wife of Leonard — joined the orchestra on the stage to do her take on Willam Walton’s “Sir Beelzebub” alongside Maestro cast member Zachary Booth, while Kate Eastman, Nick Blaemire, and Mallory Portnoy, also performed work from the film. Additionally, featured soloists Malakai Bayoh, Ann De Renais, Samuel Oladeinde, and Philip John Sheffield emerged for their parts on the fierce “Pax: Communion,” from Bernstein’s own musical theatre composition, MASS. By the time the screen behind the orchestra lit up with the climactic six-minute sequence from Maestro, in which Cooper reenacts Bernstein’s performance of Mahler’s Symphony no. 2 at Ely Cathedral in England, the majesty of the man was reverberating from every wall of the Wu Tsai Theater.

After final bows from Nézet-Séguin and the orchestra, Cooper paid tribute to Bernstein’s three children Nina, Alexander, and Jamie, inviting them onstage to receive bouquets of red roses. The evening’s program was capped with a three-way conversation among Cooper, Mulligan, and Nézet-Séguin. The wide-ranging discussion touched upon the genesis of the film and the flow of creative collaboration at the heart of making the movie.

“Watching you with the orchestra,” Mulligan said of Nézet-Séguin, “it’s an unbelievably intimate relationship with all of these people. It’s like you had a little string to every single one of them.” The kinetic nature of this special evening allowed Cooper to express what so fascinated him about the film’s subject. “The one thing that I hoped this movie could portray is the absolute miracle of this type of collective musical experience,” said Cooper. “Coming to a hall like this, watching these musicians play together — isn’t it the most incredible thing?”

Truly, the event was invaluable as a way of paying tribute and celebrating the triumph of Bernstein and his art. “The music we play is just a reflection of the life we live,” Nézet-Séguin said. “As a performer, what we put into it is the things we live, and that was certainly true of Leonard. This experience? You feel all the life and emotion.”