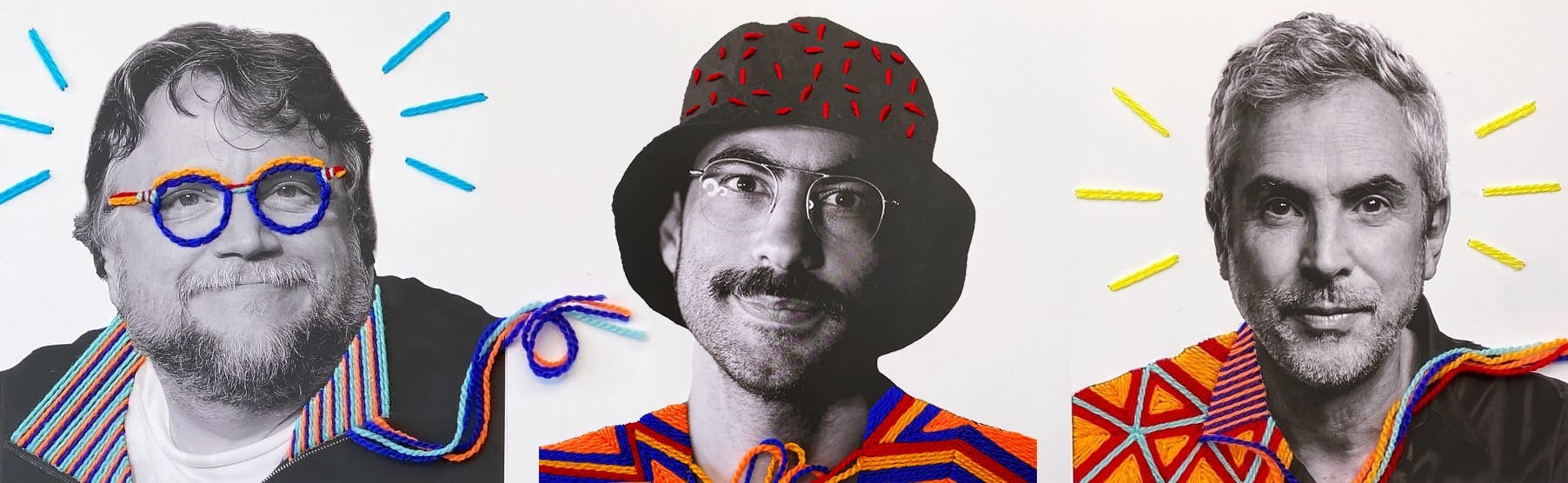

Alfonso Cuarón and Guillermo del Toro celebrate Ya no estoy aquí and the arrival of writer-director Fernando Frías de la Parra.

Since its initial release in Mexico, Fernando Frías de la Parra’s Ya no estoy aquí (I’m No Longer Here) has captivated audiences with its quietly magnificent portrait of Cholombianos, the adherents of a Mexican street culture whose distinctive fashion and love for cumbia music meaningfully define the life of the film’s protagonist, 17-year-old Ulises (Juan Daniel Garcia Treviño).

In the early 2010s, in the northern Mexican city of Monterrey, Ulises leads a pseudo-gang, a group of kids known as Los Terkos (“The Stubborns”) — played by a standout cast of first-time actors — who spend their days dancing to cumbia. They preserve a delicate existence within the city’s cutthroat landscape of cartel loyalties and government crackdowns, until the violence forces Ulises to flee for his life. He makes his way to Queens, where he moves in and out of various orbits, a teenager alone, struggling to survive, and finding that the culture that sustains him may not have a home.

Only the second feature from Frías de la Parra, Ya no estoy aquí won 10 Ariel Awards (Mexico’s equivalent of the Oscars), including the award for Best Picture. It has also made its mark on two of our greatest filmmakers: Academy Award winners Guillermo del Toro and Alfonso Cuarón. The longtime friends agree that the project is a defining statement from a world-class talent.

“Fernando has proven to be not only one of the most important directors in Mexico, but one of the truly important directors that the world has,” Cuarón says. “What he did with his film, it’s truly original.”

Ulises, played by Juan Daniel Garcia Treviño, dances over Monterrey

Cuarón and del Toro sat down to discuss Ya no estoy aquí and the promise of Fernando Frías de la Parra.

Guillermo del Toro: I think the movie has been successful because it portrays a very specific reality that exists — briefly — in a time and a space that are no more. It talks about things that are evanescent, that go away, both in terms of our culture and our identity. It’s a movie about exile. It’s a movie that by being particular has become universal. This movie is all truth. It tells you a story about the disenfranchisement of a young man in a society that changes right before his eyes. It’s rare: a movie, done so early in the career of a young filmmaker, that has the wisdom and the complete control of the medium — that is formally impeccable, but at the same time, very, very free narratively. I think it is one of the most memorable Mexican films in the last couple of decades.

Alfonso Cuarón: It’s also a film that doesn’t really have a reference in Mexican cinema. It’s a film about identity: the certainty of our identities, the defense of our identities, the challenge of how supported our identities are, how much our identities are based upon an external façade. That’s the reason I think it’s truly universal. The film has played fantastically well in Mexico, as it has played all around the world. In certain countries, it’s been embraced as if it was their own. It’s guiding us through a very ephemerous culture that we are all very unfamiliar with. On the one hand, it feels so alien. But the human experience is what makes it so universal.

Mexican cinema requires talents like Fernando to continue.

Guillermo del Toro

GDT: There are so many Mexicos. Even within Monterrey, one is the Monterrey of the rich people, one is the Monterrey of the middle class, and one is the Monterrey of cultures that exist in the periphery, outside of the big urban areas. We say in Mexico that our country gets reinvented every six years because we get a new president. This movie shows you that it’s much faster than that. It’s a very painful and beautiful movie.

AC: You called me and said, “You have to watch this movie.” You told me, “You’re going to have some expectations of where it’s going, and then he’s not going to go there. He’s going to challenge that expectation, and he’s going to go to another place that is more truthful and powerful.”

Ulises busks in New York City

GDT: Mexican cinema requires talents like Fernando to continue. He inherits a mantle that you can trace back to the golden era of Mexican cinema, with somebody like Tin Tan, who was a comedian who for the first time articulated the binational nature of Mexico, flowing back and forth from the United States and still creating a personal culture from that transitory state. Each generation of filmmakers maintains Mexican cinema in the world — even now, when the moment is very difficult because government support for Mexican cinema is vanishing.

His importance is also in fulfilling the essential thirst for truth that we have in cinema. We want people to show us the truth. We want people to show us realities that are not ours, even if we exist in the same country. The Terkos represent that acts of disobedience and stubbornness are essential in Mexico for us to survive — in a country where every breath, every heartbeat, is an act of will. This is a movie that tells us that, essentially, we are all dancing alone in the end. To do that, he needs to show us the isolation of every character and how they are divided by class, by money, by nationality, yet they can grow together.

It’s a film about identity: the certainty of our identities, the defense of our identities...

Alfonso Cuarón

AC: Part of the power of the film is that you’re invited to go into this very specific world, into this very specific vision of this filmmaker. With the wisdom that he approached his locations, he also approached his casting, casting people who are absolutely truthful to each one of these parts — most of them non-actors, both in the U.S. and in Mexico.

These kinds of films, they need to be made, and they need to be supported. Mexico now is going through challenging times in terms of production, but in the world, filmmakers like Fernando represent the torch for what is to come. Fernando, for me, is already an inspiration, and I believe that he will be an inspiration for generations to come and for people of his own generation — that they can see that what matters is really the honest vision, the original vision.

Los Terkos dance to cumbia

GDT: The Terkos, or “Stubborns,” that’s a perfect way to define Mexican filmmakers. We have kept cinema alive generation by generation through impossible defiance, just like these guys who are oppressed by so many things but understand that for the moment —for the moment— they’re dancing. For that moment they’re alive. That is the essence of making a film in Mexico. Things are against us, things are difficult, but for the moment, we dance.

Opening artwork features photography of Guillermo del Toro by Guillem Medina, Fernando Frías de la Parra by Johannes Eisele, Alfonso Cuarón by Dan Winters.