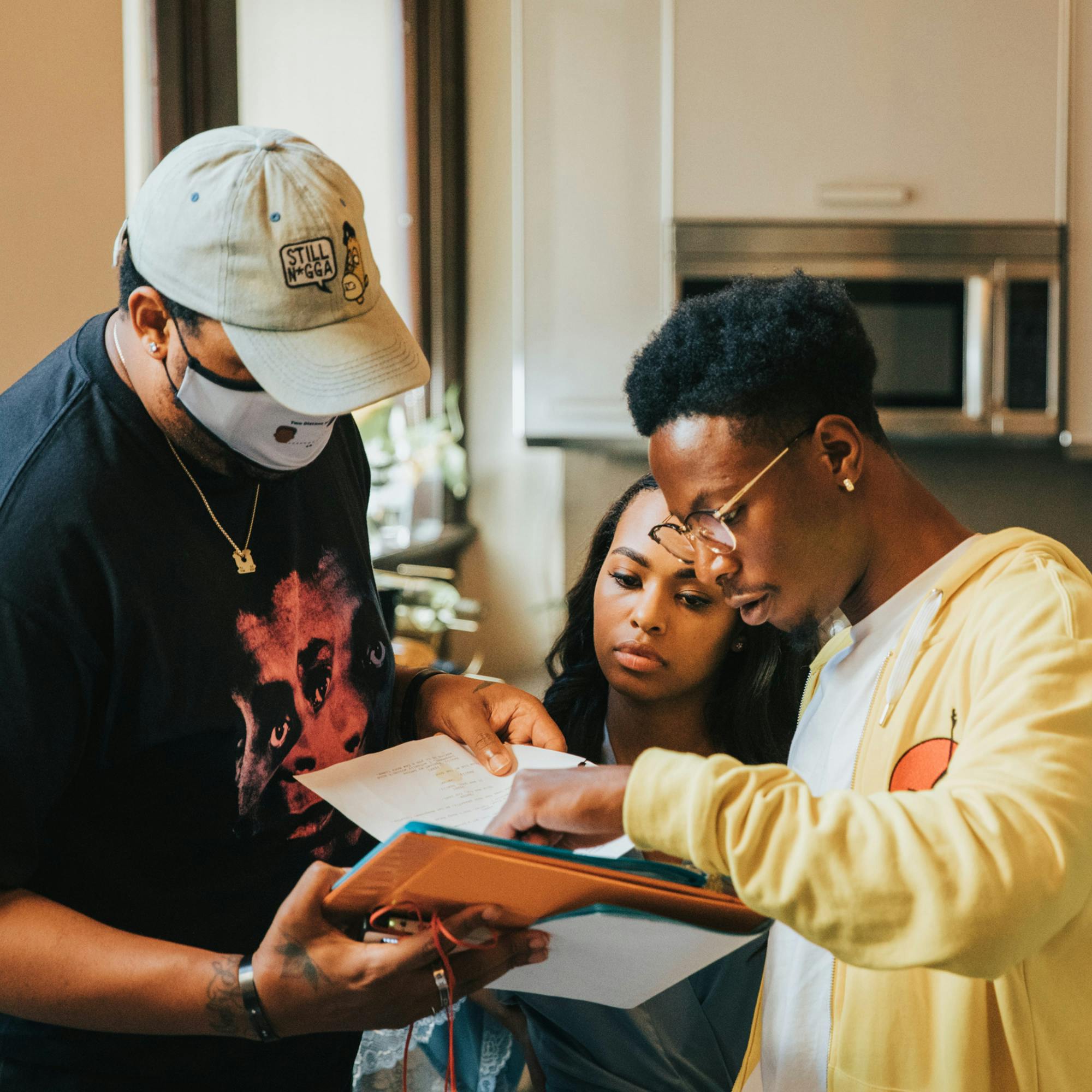

Travon Free and Martin Desmond Roe discuss their Oscar-nominated short.

George Floyd, Freddie Gray, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Breonna Taylor. An aerial shot reveals a rooftop where these names are carefully rendered in white paint. It’s a quiet moment of reflection in the Oscar-nominated short film Two Distant Strangers, which tells the story of Carter (rapper Joey Bada$$), a New York City cartoonist who finds himself reliving a fatal encounter with a white police officer (Andrew Howard) over and over and over again.

Emmy-winning writer-producer Travon Free (The Daily Show, Full Frontal with Samantha Bee) authored the film in direct response to the murders that ignited the Black Lives Matter protests last spring and summer. It took him just five days to write from start to finish. At the time he was working with Martin Desmond Roe (who wrote the Oscar-nominated 2012 short Buzkashi Boys) on another movie. He brought the fresh script to Roe, who instantly agreed to co-direct, and the pair got to work on the project amidst the added challenges of the global pandemic. They filmed over the course of five days, and within five months had dotted their i’s and crossed their t’s.

The resulting short has garnered overwhelming support from prominent figures inside and outside of Hollywood, including Kevin Durant, Sean Combs, and Lawrence Bender (known for producing classics like Pulp Fiction and Goodwill Hunting), who came on board as producers. Bender also produced the 2020 animated short Cops and Robbers, another urgent commentary on race and police brutality in America. At the height of the protests, he and Free were actually quarantining together, along with Free’s girlfriend, Zaria, who joined the cast as Carter’s love interest, Perri.

“We had this impossible litany of people that said, ‘Yes, we’ll help,’” Roe explains. “When you find the lightning in the bottle, when you find the story you need to tell, you have to march after it as hard as you can.”

It’s true the story grew out of a singular moment in history, but the conversation it joins is still unfolding. “I hope people take away the fact that what the movie makes you feel for 29 minutes is what we feel for 24 hours,” says Free. “And if you can just walk away with the knowledge of how strong and resilient Black people have been for the past 400 years to be able to have this conversation, to be able to tell this story, I think we can truly reshape the conversation around what it means to be a minority and interact with police in this country.”

Director Martin Desmond Roe and writer-director Travon Free on set

Queue spoke to Free and Roe about the immediacy, the legacy, and the making of Two Distant Strangers.

Queue: Tell us how you came to this idea. What was the catalyst for Two Distant Strangers?

Travon Free: We were all watching the world respond last year to the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery. It occurred to me on an emotional level that as you process what happens to Black people in America, as a Black person you go through the cycle of emotions from anger to sadness to hopelessness to hope. I felt like there was a story to tell to communicate that feeling to people who aren’t me, or people who don’t look like me.

When I got the idea for Two Distant Strangers, I felt like because Martin and I were already working on a movie together and he had already had experience making shorts, he was naturally the first person I should tell. He immediately saw the vision, and we were inspired to make it come to life as quickly as possible.

Martin Desmond Roe: In our industry, we all pitch each other things all the time. Every now and then someone says something and you’re like, That one. That, we drop everything for. And so we just dropped everything. It was one week, I think, after George Floyd was murdered. Everybody in the world wanted to be of service and to find a way to channel what they were feeling. Travon asked me to help, and I was like, “What can I do? I’ll do anything.” That’s the response that we got from almost everybody that we asked to help along the way, which is the only reason this film was able to happen at the pace that it was. I’ve made quite a few things in my life, but I’ve never had anything where we’d be like, “Let’s email this intimidatingly famous person and see if they’ll help,” and everybody said yes.

Writer-director Travon Free with Joey Bada$$ and Zaria

James Poyser, of The Roots, wrote a beautiful score for this film. And then the Bruce Hornsby song “The Way It Is” plays this thematic role. How did that come about?

MDR: The title of the film came from the music. From the very first draft that Travon wrote, “The Way It Is” was always an anchor point. Bruce very graciously let us use it in the film. The message of that song is still relevant however many decades after it was written: “That’s just the way it is / Some things will never change.” Then there’s this very beautiful little subpart to it: “But don’t you believe them.” He’s got this little bit of hope. It very closely mirrors the structure of our film.

It’s obviously also the sample that was used for Tupac’s “Changes,” so it’s a track that’s had this life in the activist space for decades now. We were like, “I wonder if there’s anything in the lyrics of the Tupac version that speaks to the film?” And there’s this line in there: “Learn to see me as a brother instead of two distant strangers.” We were like, “That’s it. That’s our movie.”

When you watch the movie, it’s difficult to walk away feeling like it’s anything other than a story of hope and resilience.

Travon Free

TF: I immediately knew I wanted that Hornsby song to be the thread through the film because it was a song that was written the year I was born, 1985. It was a song about the same thing we’re talking about today in 2021. “But don’t you believe them” — that’s where we live. We experience “that’s just the way it is,” but we refuse to accept it. That was something I wanted to tie the entire film together.

Joey Bada$$ and Travon Free

What was it like to create this film in the midst of COVID-19?

MDR: Getting this thing organized in the pandemic was one of the greatest practical challenges of my filmmaking career. We knew two things: We knew we had to make the film, and we knew nobody could get sick because they were making our film. It gave the crew such a sense of unity. We all had to quarantine; we all had to go through these tests. This was everybody’s first job back — that was why we were able to get such an incredible crew! Everybody had been sitting around waiting, and then you call them, like, “Hey, we’ve got something that matters.”

With the events that Carter goes through again and again, you are referencing real peoples’ experiences of police brutality, experiences that were collectively front of mind in 2020. There are scenes in this film that are difficult to watch.

TF: It’s important to know that those scenes aren’t what the movie is about; they are a means to an end. Our film is not centered in trauma; it takes trauma and takes you on a journey that leaves you feeling differently. It was important that the experience that Carter was going through was not voyeuristic. It was, Why is this happening? How is this happening? What can I do about it? As a filmmaker, I’m accepting this trauma in order to create something that is bigger than me. Given my own experiences with police, it was important that this story be told the way it is. When you watch the movie, it’s difficult to walk away feeling like it’s anything other than a story of hope and resilience.

MDR: We are examining and remembering these extremely painful key cultural moments. You’re definitely aware of the power of those images. Travon thought very deeply when he was writing the script about why and how to use that imagery. It is very powerful when you use it right now knowing that tomorrow we might see the same thing again on television.

Merk (Andrew Howard) and Carter (Joey Bada$$)

Why was it important that you make this story at this particular moment?

MDR: As someone who doesn’t experience that fear and that oppression, this acts as a vehicle. It felt important for us to do it now and to do it quickly because it’s like, Does anybody deserve to feel like this every time they walk out their door? No matter who you are, the answer should be obvious. Making the film was an act of friendship, love, service, and learning. I’ve been in some really incredible rooms doing this with Travon and some really thoughtful people from the Black film community who wanted to make sure that the story that was being told here resonated deeply and honestly and widely. I learned so much from those rooms.

TF: The reason I needed to tell this story and I wanted to tell this story was because it was an immediate response to what I was feeling as a person, as an artist. Part of our job as artists is to reflect society and to reflect life. This was a story that a lot of people I knew were also experiencing. And because the world was experiencing these things at the same time in a way that we had never seen before, it felt like there was no better time to tell this story.

It felt like we were channeling our anger and our rage and our emotional exhaustion around the issue into something that when we got distanced from it, people could appreciate, and people could understand, and it could really be indicative of the time that we lived in last year. The fact that we were able to do that and get this piece out into the world to coincide with those things is not only a testament to short filmmaking and the power of it and how responsive it can be, but a testament to the nature of art and art responding to society.