Queue explores Netflix’s collection of true crime, and what it can teach us.

Growing up with the name Miranda, I spent a good portion of introductions being asked whether I knew I was allowed to have an attorney present and, sometimes, by the most annoying people, to recite the Miranda warning aloud. At first, I’d casually respond that I was named after Carmen Miranda and slowly back away, but it was only a matter of time before I became curious about the Miranda rights and wondered why I (or anyone) needed them. I eventually found the answers I needed in true crime shows and documentaries.

I’m now that woman who’s watched and rewatched every single episode of all 22 seasons of Law and Order: SVU, a series that bills itself as “ripped from the headlines.” It’s so familiar that I often fall asleep watching: Stars Mariska Hargitay and Ice-T’s voices are my ambient waves crashing on an unseen beach. Perhaps it’s the occasional mention of my name that provides me a sense of comfort. Or perhaps, when it comes to true crime, that comfort comes from feeling seen.

My obsession with the genre started with the gigantic box-size TV set in my childhood living room, which I lay in front of every evening while doing homework. Growing up, I’d get home by taking two buses through San Francisco wearing my Catholic school uniform, which, according to what I saw on television, was practically like begging older men to hit on you. Once home, I’d lock the door and get into the serious business of watching sexy hip-hop music videos on the public access station for an hour or so. Then, around 6 o’clock, the news broadcasts would take over with headline reports of women who had something bad happen to them, ostensibly because of some action they forgot to take or the way they acted or dressed. Sometimes, when my mother got home, we’d dive deeper, watching 60 Minutes, 20/20, or America’s Most Wanted. It seemed there was no dearth of occasions or methods by which a woman might die.

Unsolved Mysteries

My immigrant parents reinforced the notion that the decisions we make play a large part in our safety. My father’s mantra, which came from growing up in the streets of Ensenada, Mexico and San Francisco’s Chinatown, was always, “If you see something bad happening, walk the other way. You don’t want to be there when the cops show up.” My Filipina mother was (and is) a look-out-for-yourself type who believes that if something bad happens to you, it’s your own fault. She recently advised me to stay away from trees, lest one fall on me and leave me disfigured.

More practically, she made me aware of the very real and terrifying potential of kidnapping, rape, and murder as I “galavanted” around town with friends (how a word like “galavant” became a standard part of the Filipino lexicon, I’ll never understand). She wasn’t wrong, but that danger had a lot to do with the way many men treat women, and a lot less to do with women’s dress or actions — I had to learn that through experience.

One day, as I was waiting at a crosswalk on Geary St. (dressed very prudishly), a beat-up four-door pulled up beside me at the stoplight. I noticed that the backseat was filled to the brim with knick-knacks and furniture. The driver, a scruffy older man, rolled down the passenger side window and reached out to me — “Get in the car,” he said, touching himself and muttering a few choice phrases about my appearance. “No thanks,” I said (in retrospect this was too polite of a response). He opened the door, rolled the car closer to me, and commanded, “Get in now.” With that, I took off down the street, looking over my shoulder for blocks.

That wasn’t my only brush with lewd men; there was the time I saw a man jerking off in his car outside my high school, and all the times I put up with unwanted sexual phone calls while working at bookstores. Walking home alone at 4 a.m. through the emptied streets of Madrid (clearly a vodka-limón-based decision), I was followed by a car full of dudes hurling pickup lines for blocks. I could also tell you about the weeks where I struggled to leave the house because a rapist was terrorizing my neighborhood.

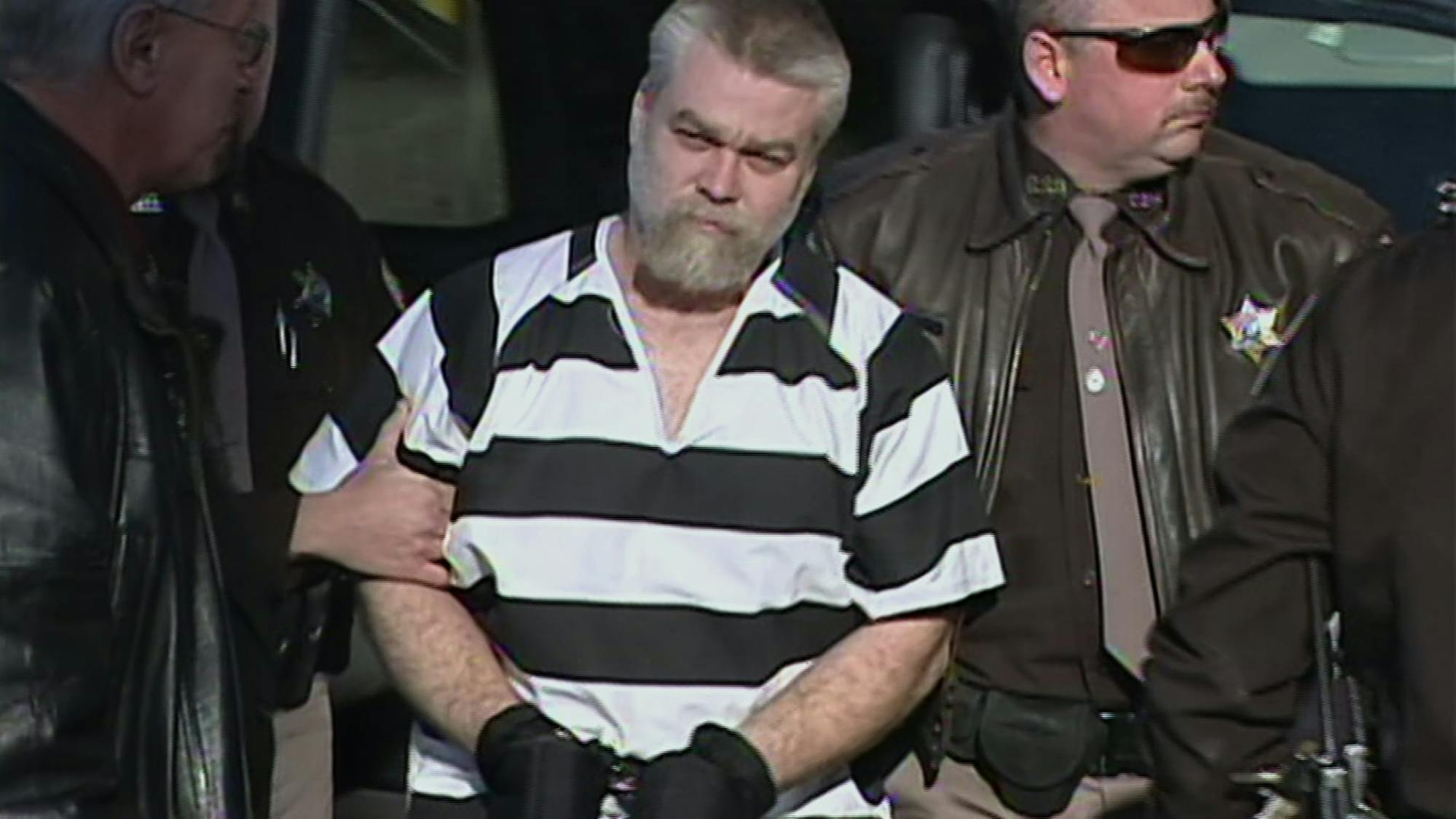

Making a Murderer

The thing is: These are everyday experiences for women. These incidents are so commonplace that they’re barely memorable to me, but that’s just because I’ve been lucky in my encounters. There are plenty of people for whom that’s not the case. That’s why many women love true crime; it validates our experience with the world, one that only really gets acknowledged when something extreme or deadly happens. It tells us, yes, this happens, and especially to women. It allows us to explore the world of “what if” responses that might be essential to our survival, show empathy and support for those who’ve suffered tragedy, or join the cause of freeing an innocent person — or finding a killer — when we often feel powerless to end these crimes.

And although I clearly enjoy the genre, it’s not something I come out with often. Admitting you love true crime is, well, embarrassing. Even as I write this essay, I’m cringing — hard. I’ll talk you to death about the joys of lowbrow reality television and terrible movies, but I try not to discuss true crime unless pressed. Aficionados have the unfortunate reputation of being rubberneckers, ambulance chasers, morbidly obsessed, and nosy. Some might even say we have no taste, given that most true crime we grew up watching consisted of a handful of repetitive interviews, gross reenactments, and crime-scene footage, properly mocked in Bill Hader’s SNL impression of Dateline host Keith Morrison.

Thankfully, it seems as if the golden age of television has finally arrived for today’s true-crime content. Granted, a documentary about the tragic death of JonBenét Ramsey seems to come out every year (unsolved, this story continues to fascinate and inspire theories — watch Casting JonBenet for a meta-take on this case). And we’ll never ever begin to hear the end of Ted Bundy, a man whose crimes prey on women’s deep-seated fears that a quasi-attractive and seemingly-harmless-but-actually-murderous man lurks around every corner, waiting to be invited to our parents’ house for dinner.

But there’s also a new wave of true crime that aims to tell stories that the news forgets or ignores, stories where the takeaway is often a profound lesson about society’s failings rather than a brash rehashing of some salacious case. Whether you’re ready to dive in or simply true-crime curious, here are a handful of excellent series and documentaries that do the genre proud.

Las tres muertes de Marisela Escobedo (The Three Deaths of Marisela Escobedo) takes place in 2008 in the Mexican state of Juárez, where Marisela Escobedo’s 16-year-old daughter Rubi disappears and is eventually found burned and dismembered on a hog farm. Her live-in boyfriend confesses to killing her, but a tribunal of judges decides that his confession is coerced and that there’s not enough evidence to convict, so they set him free. Marisela and her family take just one day to mourn before they’re out on the streets campaigning for justice for Rubi — and symbolically for all the unresolved cases of women killed by their romantic partners. Shining a spotlight on domestic violence, this documentary depicts the many ups and downs of the case and underscores the danger of seeking justice for women in a corrupt system. I was especially moved by the centering of Marisela’s two sons and their continued activism on behalf of their sister and mother.

Strong Island

“You do not know that your death may, in fact, be the actual death of our family. You do not know that we are silent in our grief, even with one another.” Yance Ford, the creator and narrator of Strong Island, recites these words as she reenacts her brother William’s death — William Ford was shot one night while attempting to get his car back from an auto body shop after a series of arguments with the shop’s workers. From the very first moments of Strong Island, you experience the crushing weight of the Ford family’s grief. The documentary poetically interweaves devastating family photos, fragments of William’s case files and journals, and memories of living as a Black family in a segregated 1970s Long Island. Strong Island isn’t just the account of one family’s tragedy — it also offers a sobering look at how systemic racism continues to widen the racial divide in the United States.

Who would’ve thought that an episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm would literally save a man’s life? Long Shot is the horrifying story of Los Angeles man Juan Catalan, who is very nearly convicted of a murder he didn’t commit. He manages to avoid prison time due to an unassailable alibi; thanks to a chance taping of the comedy series, Catalan could be seen in the stands of a Dodgers’s game. As the film takes you through the unlikely journey to acquit a misidentified man, the “what ifs” of the case are haunting: What if the show had been shot in a different part of the stadium? What if Juan had watched the game from home? Who would have believed him?

The Innocence Files

Although Juan Catalan’s story has a happy ending, many people who continue to protest their innocence are nevertheless sentenced to prison-time (Making a Murderer’s Steven Avery, who insists he was framed for first-degree murder, remains jailed). True-crime shows about unsolved cases and wrongful convictions are so common, they’re almost their own genre. John Grisham’s The Innocence Files highlights the work of the Innocence Project, a nonprofit organization working on behalf of those who insist they were unjustly convicted. Pouring over cases, the group’s attorneys will often seek to obtain and introduce DNA evidence that was perhaps unavailable as the case was being tried or to dismiss evidence that has since been discredited (blood spatter, fingerprint, and firearm analysis; bite mark evidence, etc.). As said in the new Netflix documentary Sophie: A Murder in West Cork, “Justice has no time limit.” And with so many innocent people being freed from prison, it begs the question: Who did commit the crime?

Let’s talk about the power of collective knowledge. Obviously, the internet has got a lot wrong with it — at age 13, I was surfing AOL and a/s/l-ing strangers left and right, which could have led to something bad, except that I’m very smart and hugely afraid of meeting people. Today, the internet is still used for nefarious purposes like selling drugs, founding cults, and catfishing, but we also have cadres of online sleuths who puzzle over unsolved cases like they’re trying to get out of an escape room. Like me, these people grew up seeing faces on milk cartons or watching episodes of Unsolved Mysteries and Cold Case Files, feeling powerless. But today, the internet is harnessed as a network of crime-solving.

Take Don’t F*** with Cats as a prime example. This gruesome story begins with anonymous postings of videos depicting animal torture, escalates to murder, and is followed in real time by concerned screen names who dig into the most miniscule details of each video to track down the aggressor’s whereabouts. I won’t spoil it, but it’s truly amazing what these amateur detectives were able to accomplish via the internet.

Crime Scene: The Vanishing at the Cecil Hotel

On the other hand, Crime Scene: The Vanishing at the Cecil Hotel shows the danger of playing Sherlock Holmes online. I remember hearing about this case when it happened in 2013; Canadian student Elisa Lam goes missing during her stay in downtown Los Angeles’s Cecil Hotel but leaves behind a trove of digital breadcrumbs via her Tumblr diary. There’s also mysterious footage of Elisa in the hotel elevator, conversing with an unknown, unseen person just out of view, or perhaps, with no one at all. When Elisa is eventually found in the hotel’s water tank — yes, guests drank that water — the questions only grow: How did she even get in there? And why?

Theories pointed to Mexican death-metal singer Pablo Vergara, aka Morbid; he had recorded songs and videos about murder in L.A. and even filmed one video inside the Cecil Hotel (albeit a year before Lam was there). Although he had a strong alibi — he was recording in Mexico at the time — he was inundated with messages declaring him the killer. Vergara later admitted that he tried to take his own life as a result of the harassment: “The web sleuths go on with their lives like nothing happened. But they really turned my life upside down. I do feel like I have lost my freedom of expression. I actually haven’t made any more music.” The Vanishing at the Cecil Hotel offers an in-depth examination of a fascinating case but also underscores the consequences of jumping to conclusions.

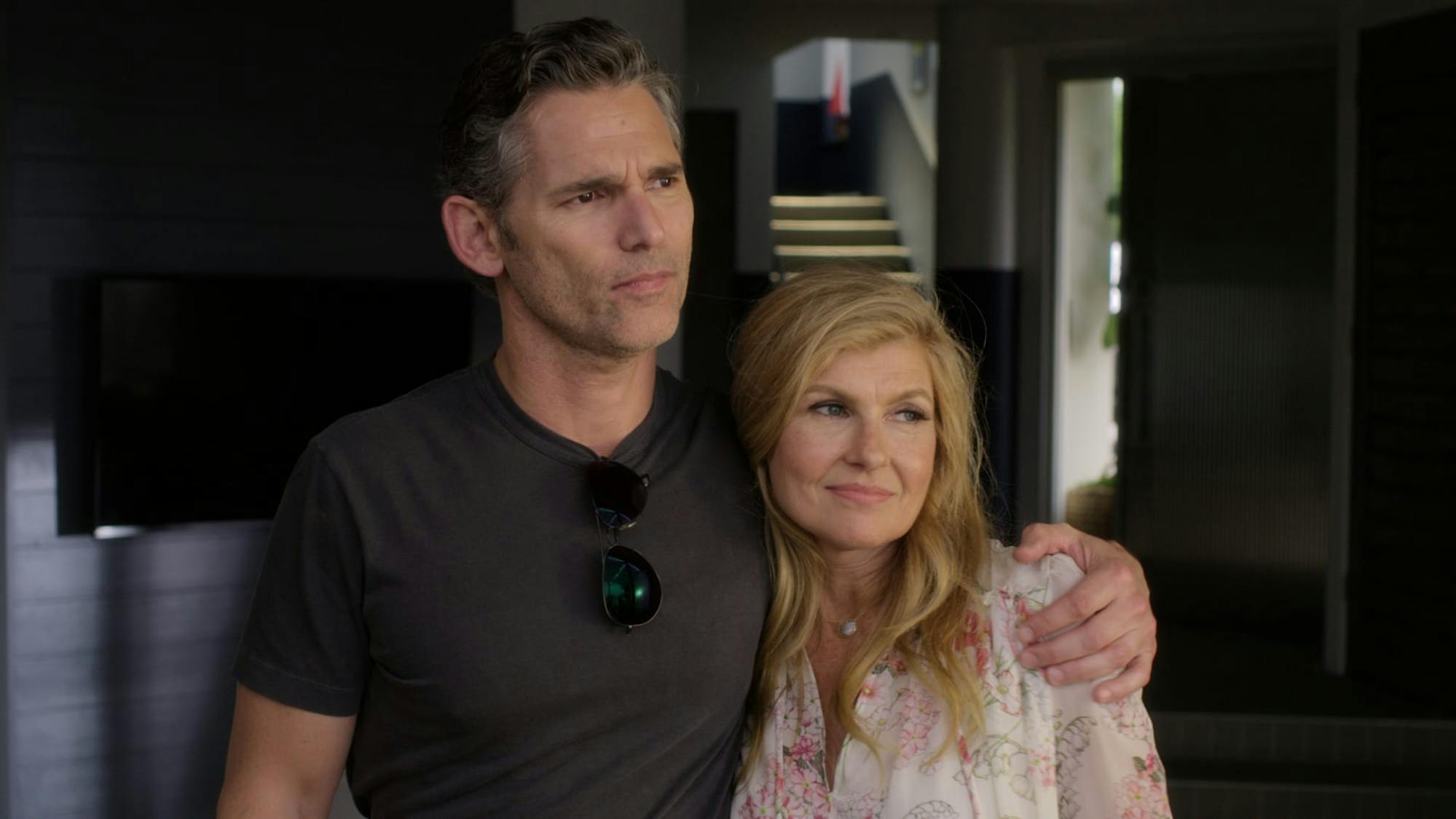

And then there’s Dirty John, a show so deliciously soapy, you might feel guilty watching it. Although both seasons of anthology series Dirty John lure us in with fictionalized versions of actual family dramas, we watch because of the very real way the show depicts gaslighting and other mental and emotional violence against women. Originally based on a podcast of the same name (that itself was based on an L.A. Times article), the first season follows Debra Newell (Connie Britton), a divorceé many times over, who hasn’t given up hope of love. As she begins dating doctor John Meehan (Eric Bana), who her children immediately dislike, we get to see the buried family history that informs Debra’s decisions. While there is something icky about fictionalized true crimes and the enjoyment we feel watching well-made television about something so terribly real, I appreciate that these shows meet the audience where they’re at. Fans are used to watching shows in this format that reinforce negative stereotypes about women and relationships, or at least normalize a heightened chaos of cheating, lies, and deception (speaking of which, am I the only one who misses Passions?), but soapy true crime offers lovers of daytime drama something a bit more meaningful to chew on.

Dirty John

Money can buy more than designer clothes and McMansions. It can also purchase superb legal counsel and greatly influence how the legal system treats you. (See Jeffrey Epstein: Filthy Rich, Fyre: The Greatest Party That Never Happened, or Operation Varsity Blues for proof.) Award-winning 2004 French docuseries The Staircase was among the first projects of its kind to offer an inside look at the advantages of a well-funded legal defense team. From blood spatter analysis to trips to Germany to interview the family of Michael Peterson’s former wife (Elizabeth Ratliff, who also died on a staircase), these lawyers are able to accomplish a lot on behalf of their client. After watching this, you won’t doubt that money can set you free.

The Staircase