David J. Bomba designs the house — and instrument — at the heart of Malcolm Washington’s August Wilson adaptation.

Throughout Malcolm Washington’s The Piano Lesson, the question of how to heal a family’s generational wounds unfurls around the title instrument. Adapted from the fourth play in August Wilson’s American Century Cycle, the film takes place in 1930s Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Sharecropper Boy Willie (Tenet’s John David Washington) arrives at his sister Berniece’s (Till’s Danielle Deadwyler) house hoping to sell their family heirloom so he can buy the Sutter family’s land, where their forebears were once enslaved.

This inheritance, however, is fraught, as it was passed down by their father, who was murdered by Sutter, and the instrument’s facade bears intricate carvings of their ancestors. The piano resounds with the ghosts of suffering and communion past, ricocheting the siblings in opposing directions regarding what to do about the instrument — and the legacy it represents.

Crafting the piano at the Pulitzer Prize-winning story’s complicated center proved to be an immersive creative challenge for the film’s production designer David J. Bomba. The designer had worked on films contending with the history of racism in the U.S. before, including Mudbound and The Great Debaters, as well as adaptations such as the Tom Wolfe series A Man in Full.

Here, the two-time Emmy-nominated designer (Ozark) shares how he approached building the layered worlds of The Piano Lesson, and the pivotal prop wedged between Boy Willie and Berniece’s approaches to reconciling the past and paving a new future. “I just got so excited about this project,” says Bomba. “It was one of the most fulfilling creative experiences I’ve ever had.”

Thinking outside the stage play

The nature of this play is that it takes place in the house. Through conversation and dialogue, you are taken out of it. But visually, I wanted to make sure that this house was interesting because we were going to be spending hours and days filming in it. There’s an ethereal nature to the action. You’re in an intimate storytelling environment, then, all of a sudden, Malcolm takes us out of it by way of flashbacks.

Seeking inspirations

August Wilson wrote about a real environment, real locations. And since we weren’t going to be able to film in Pittsburgh, I wanted so badly to be able to tie Pittsburgh and the reality of the Hill District [a majority African American neighborhood in the early twentieth century] into what we could do in Atlanta [where we filmed].

I went back to the Works Progress Administration photographers. Eudora Welty has a piece titled Home By Dark, and Malcolm introduced me to Jacob Lawrence, who was a contemporary of August Wilson’s and painted imagery of the Hill’s jazz musicians and social events; and Carrie Mae Weems, the contemporary African American photographer [behind] Kitchen Table Series. We studied those photographs because so much of the play takes place around a dining room table. Malcolm wanted to honor the painter Ernie Barnes [whose work was featured in the credits of the show] Good Times with the characters at the Crawford Grill [an iconic Hill District jazz bar].

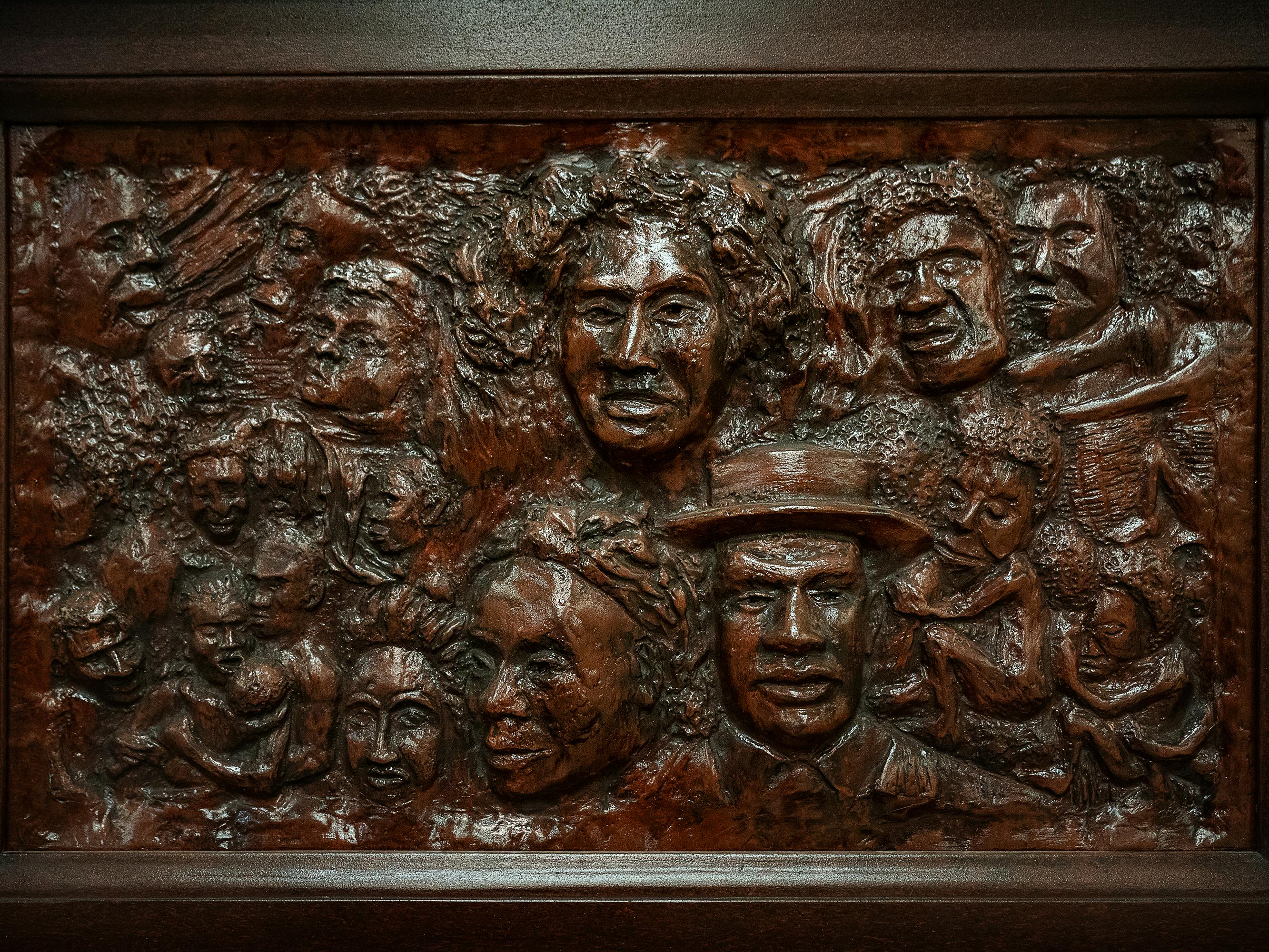

The faces of The Piano Lesson

Throughout the whole production, the focus for me was on identity and recognizing every face, every person — living people, people that had passed, and people that were prominent in this community and in August’s world. We pulled from Malcolm’s family and I represented them in both the piano and the imagery that’s hanging on the wall in the house. The energy and love that family has for each other poured out to the rest of us on set and just enveloped us. I was so well-supported in my quest to do this right. It goes deeper than just the characters on the page.

Tapping into the piano’s painful backstory

I wanted the piano to be real. It’s traded for two human beings — that’s a real thing. You have a piano that is carved by an individual who has literally been grabbed from his home country in Africa, transported across an ocean, enslaved in Mississippi. He has sculptural and carved references from his homeland, but he also is going to have references from where he lives now. It was a melding of cultures.

In film, you don’t know where the camera is going to land. You don’t know what the director, cinematographer, or actor is going to focus on. So for the development of the piano, [we needed] a clarity of story where individuals were recognized.

Building the piano

Justin [Jordan] was our assistant art director that I hired for the piano. He worked directly with Mitch Mitton, our sculptor. Malcolm found an illustration that he thinks was from one of the very first theater productions, that showed these two hero images of Boy Willie and [his mother] Mama Ola in a medallion cameo format. Justin did sketches and Photoshopped outlines for us to review. We had a pair of legs that had to be carved, two side panels, and three panels on the soundboard of the piano. Each of those went through at least three or four full-scale iterations.

Mitch’s studio was about an hour away from the production office and stage space, and I was going back and forth, sometimes twice a day. I couldn’t bring the actual element back, so it would have to be a picture and Malcolm would say, “We need to make the eye a little bit clearer,” or “This expression needs to be a little bit more tender.” It was that specific.

It was all carved in clay, then resin molds were cast and turned into what would look like a wood-grain carved piece. The camera was going to come in close-up, so every single thing had to be exact. It was exciting and stressful and nail-biting. Up until almost the night before it debuted, we had to make tweaks. But at the 11th hour, it all came together.