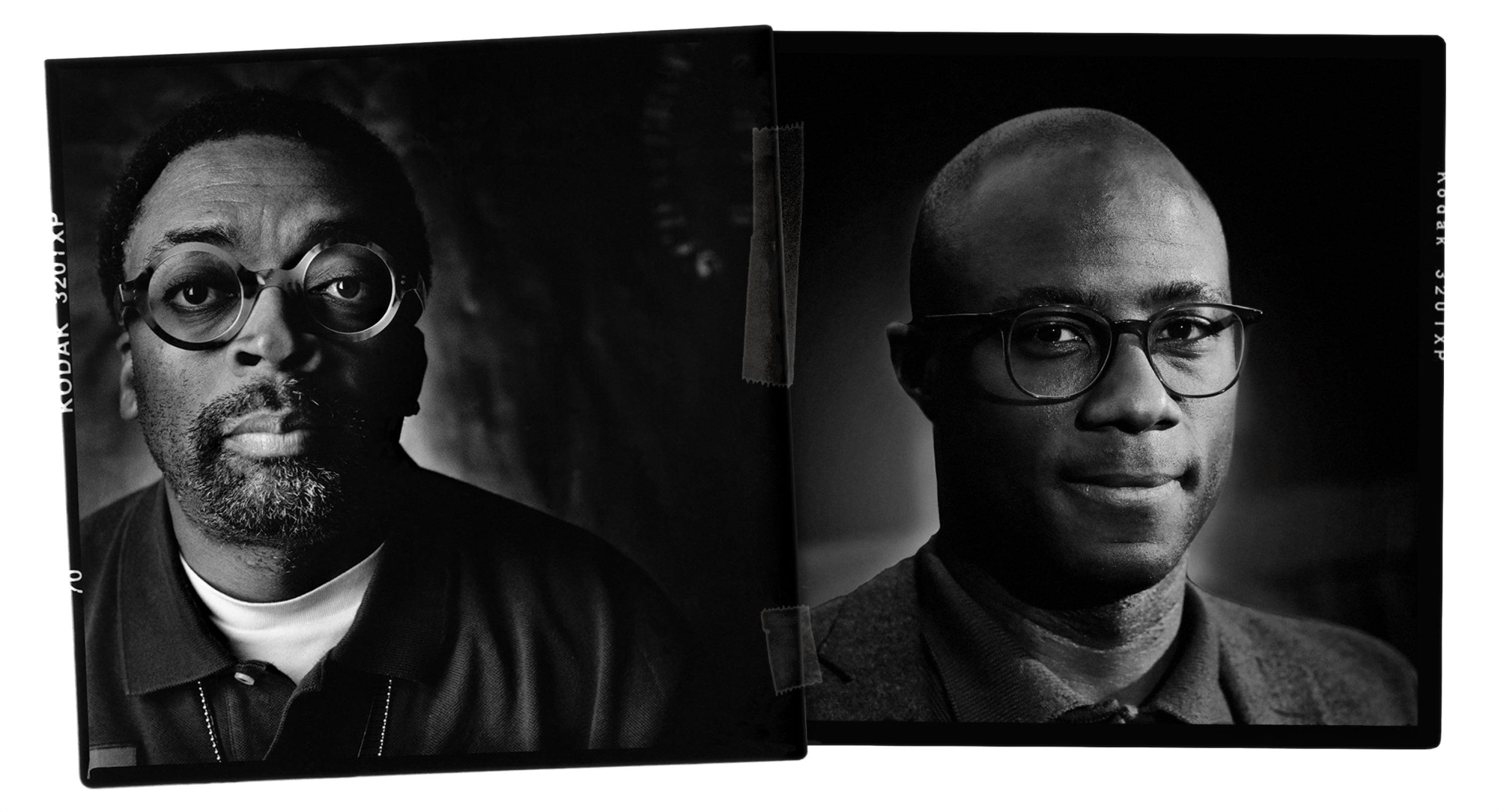

Spike Lee and Barry Jenkins talk the legacy of Black veterans in America and the making of Da 5 Bloods.

Da 5 Bloods is unmistakably a Spike Lee film. The epic won’t be constrained. It mines the history of the present, it confidently educates. For the Bloods — the Black veterans at the center of the film — American war remains encompassing decades after they’ve left Vietnam.

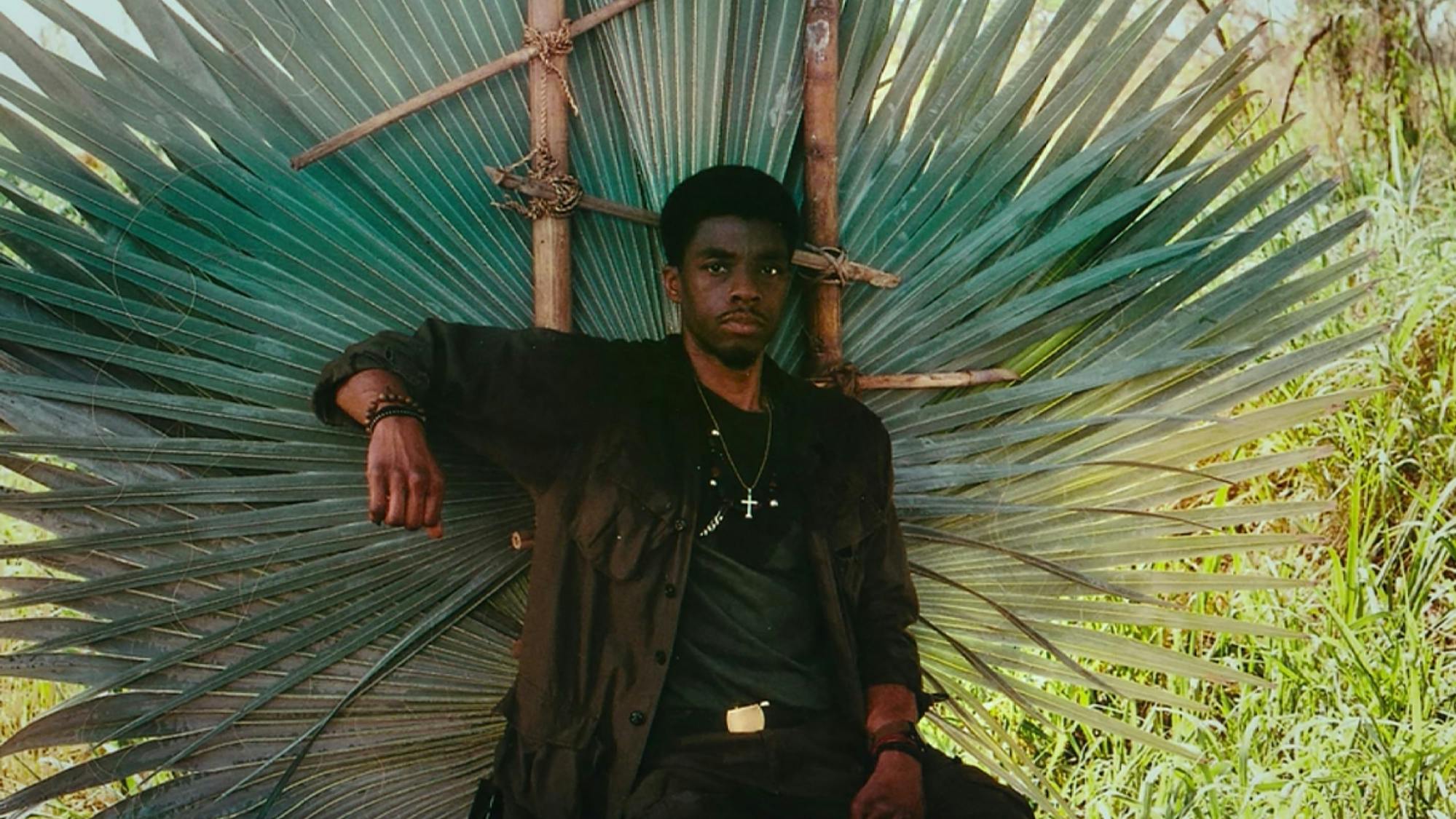

The film is Lee’s incendiary follow-up to the Oscar-winning BlacKkKlansman. It chronicles the experiences of four Black vets — Paul (Delroy Lindo), Eddie (Norm Lewis), Melvin (Isiah Whitlock Jr.), and Otis (Clarke Peters) — who return to Southeast Asia to claim the body of their fallen squad leader, the charismatic Stormin’ Norman (Chadwick Boseman), as well as a cache of gold they left buried in the jungle during the war. The quest leads Paul into ferocious combat with his P.T.S.D., climaxing in a monologue that Lindo delivers with magnetic force.

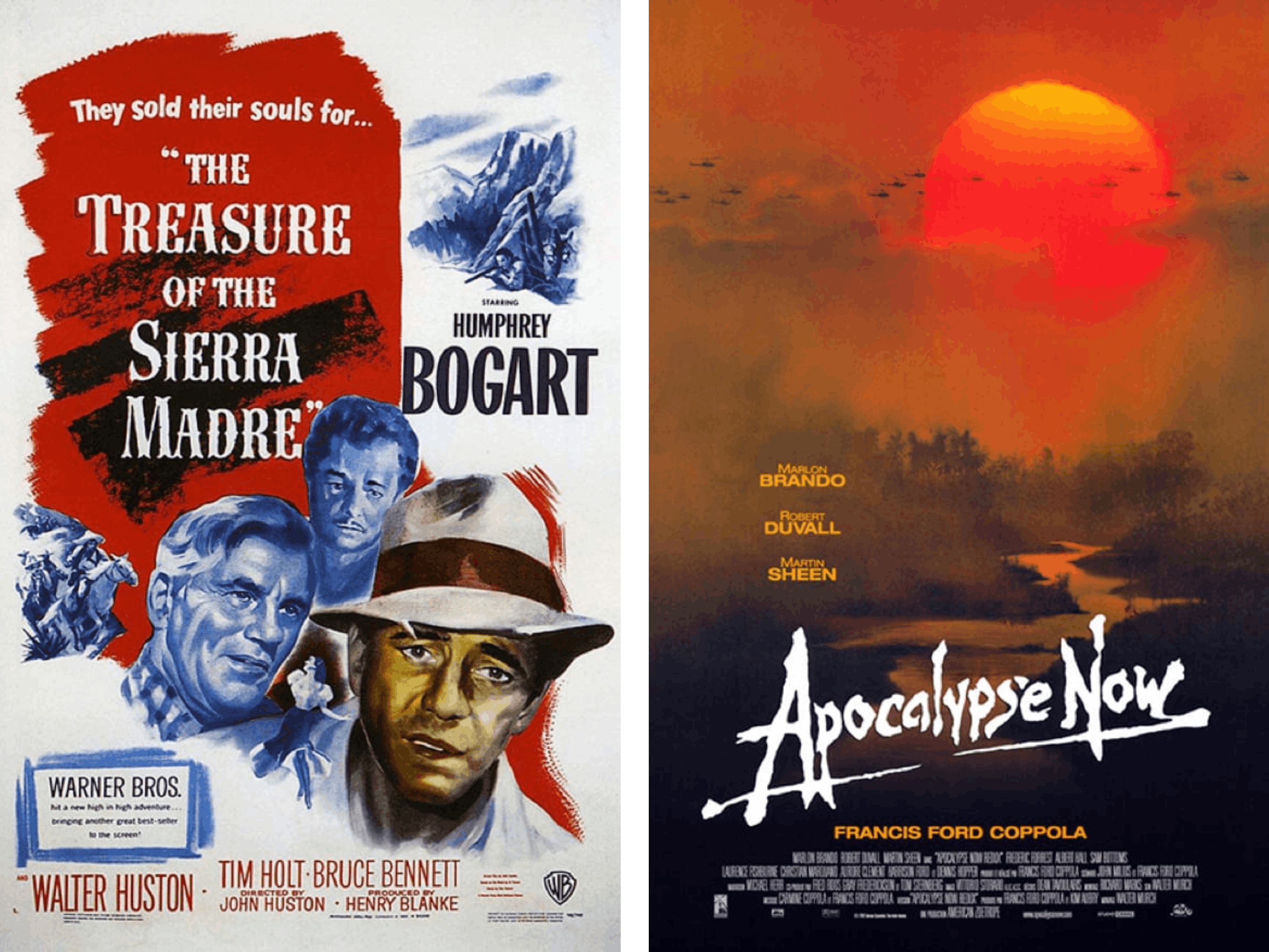

Da 5 Bloods taps into a trove of references. It pays prominent homage to Apocalypse Now and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre; it even echoes another Lee film about the experience of Black soldiers, Miracle at St. Anna, elaborating different themes and new traumas into a story all its own. Music is key here, too. Lee and his longtime composer Terence Blanchard build a scaffold out of Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On, an album whose potent social discourse is drawn in part from Gaye’s personal experience with the Vietnam War.

Da 5 Bloods’ flashback sequences represent another confident move from the filmmaker. They are shot in 16mm and take on the cramped aspect ratio of pre-widescreen Hollywood. Within that frame, the cast play their characters’ younger selves. Thus the worn, present-day Bloods return to the battlefield of years ago, where Stormin’ Norman remains preserved like a myth, young as he was when he passed.“

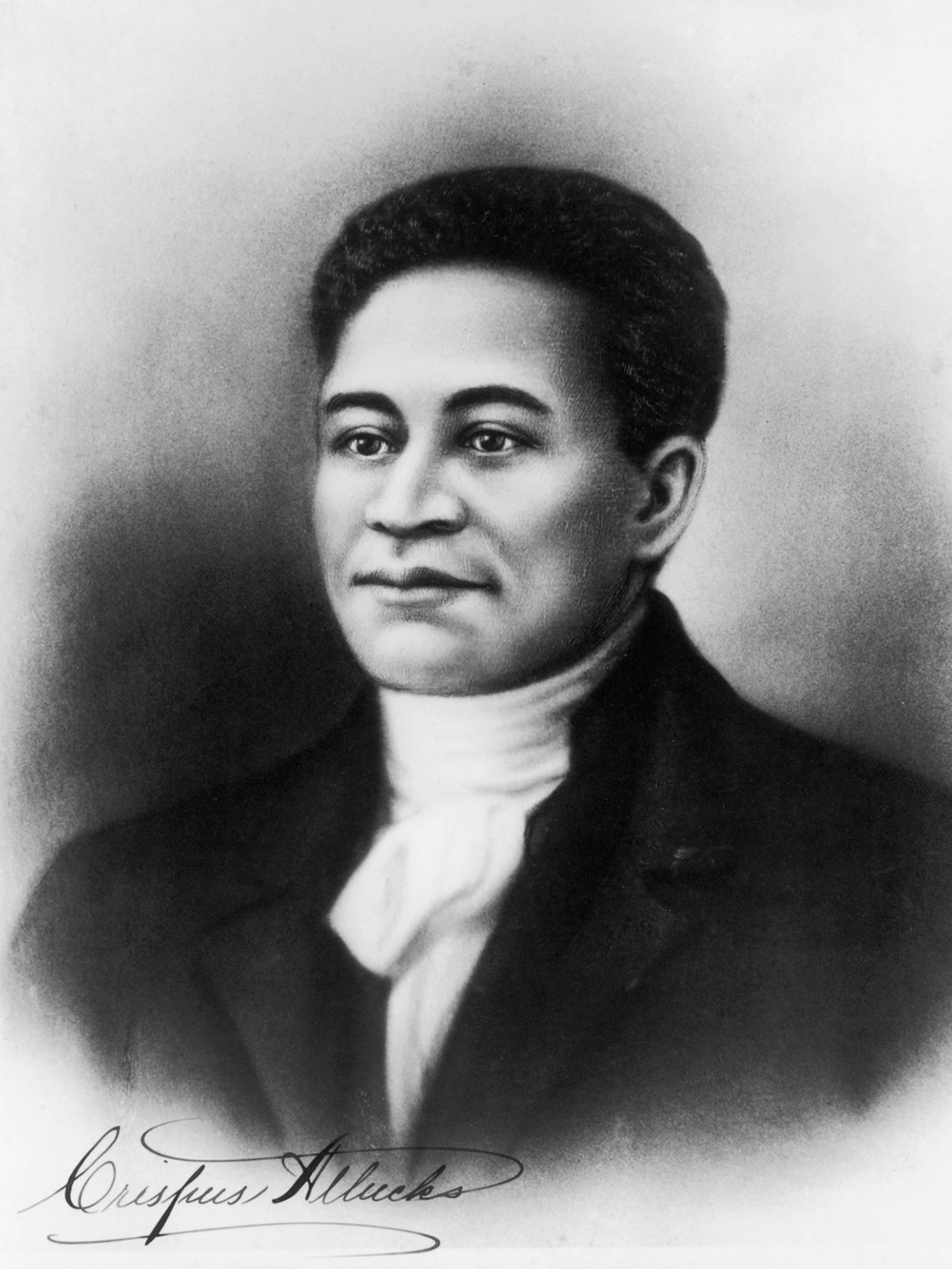

Spiritual-wise — whatever you want to call it — there were things happening on this film,” Lee says. “The first person who died for this country was a Black man. Our brothers and sisters have been fighting for this country from the get.”

Original posters for The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and Apocalypse Now

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre image courtesy of LMPC via Getty Images; Apocalypse Now image courtesy of Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images

Isiah Whitlock Jr., Norm Lewis, Clarke Peters, Delroy Lindo, and Jonathan Majors in Da 5 Bloods

Image courtesy of Netflix

In a conversation organized by the American Cinematheque, Lee spoke to Barry Jenkins — the Oscar-winning filmmaker of Moonlight and If Beale Street Could Talk — about Da 5 Bloods.

Barry Jenkins: We were both at the Oscars when you won for BlacKkKlansman, deservedly. I remember seeing you at the party that night. It was you and Regina King. Y’all both had y’all Oscars. Y’all were dancing. You were like, “Shit, I got to get on a plane tomorrow,” because you were going to make this film.

Spike Lee: I was going to Bangkok. That morning. I didn’t go to bed. I had already packed my bags before.

BJ: I swear, the same energy you had that night — you had the Oscar, you had the Artist Formerly Known As symbol — I feel all that same energy in the film. I want to know how the project got off the ground, how you came into it, just the feeling of making it.

SL: The story is this: Two writers, Danny Bilson and Paul De Meo, they wrote this script on spec that was picked up by Lloyd Levin, and he gave it to Oliver Stone. It was called The Last Tour, and four of the Vietnam vets were white and one was Black. Oliver decided not to do it. Lloyd read an article in The Guardian where I was talking about The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. He called me up. I loved the script, but I said, “If you want me to do this, I have to tell this through the viewpoint of African-American Vietnam vets. I brought in my co-writer, Kevin Willmott, and we put some hot sauce on it.

The key thing, though, was Marvin Gaye. What’s Going On is one of my favorite albums, one of the greatest albums of all time. (I was in high school when it came out. I had the vinyl, 33 long-playing.) Marvin’s older brother did three tours in Vietnam. He was a radio operator. He was writing Marvin; Marvin was reading firsthand accounts of what his brother was seeing: War is hell. When will it end? Also, Marvin was seeing the Bloods come back to Detroit. They were all fucked up, many on heroin. I think those things really led him to where the album is. Right away, I knew I wanted the songs, because they would be another character in the movie.

Marvin Gaye poses for a portrait session for his album What’s Going On, May 1971

Photo by Michael Ochs Archives / Getty Images

BJ: I want to talk about Kevin for a little bit, because y’all... it’s kind of back to back now.

SL: This is our third film. There was his project — I co-wrote it —Chi-Raq. Then we co-wrote BlacKkKlansman. We’re both tenured professors of film. He’s a tenured professor at University of Kansas; I’m a tenured professor at N.Y.U. graduate film school. We’re cinephiles. We also understand how there’s been a lot of false narratives in films, and we try to shed some light on that darkness that’s been out there for many, many years.

The opening of BlacKkKlansman is from one of the greatest shots ever in cinema, with Scarlett O’Hara. I think Gone with the Wind should be seen. I show The Birth of a Nation in my class. I also give it historical context. I talk about the things that David Griffith innovated. When they screened that film for me at N.Y.U., they left out the fact that at that time the Klan was dormant, and this film brought life back to the Klan — which directly ended up killing Black folks. That was not taught.

BJ: That leads me to Delroy’s character in this film, Paul. He’s a Trump supporter. What I love that you do with it is you create the context of how a man like that could become that person. The character Paul was not in the original piece, I imagine.

SL: Paul was in it, but the script was written before Agent Orange got in the White House, so it was Kevin and I that did that whole thing. The reason why we did that is because when you’re in a war or in a battle, that bond, you can’t break it. When the Bloods came back to the world from Vietnam, everybody went their separate ways. This is the first time they’ve all been together. It’s a buddy film, but still you’ve got to have some beef, some static, just for drama. So Kevin and I, we said, “What’s the wildest thing we can do?” And you can see the result. There’s very few — but they are there — people who drank the Orange Kool-Aid.

BlacKkKlansman opens on a scene from Gone with the Wind

Photo by Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Delroy Lindo as Paul

Image courtesy of Netflix

BJ: You’ve been very vocal about your opinions on Agent Orange. Then you had to crawl inside someone who could go to the point where they could endorse that man. I imagine that wasn’t easy to do.

SL: All Kevin and I had to think about was: This is a guy who’s never got a break in his life. Never. His wife dies giving childbirth. Consequently, he’s blamed his son and has tormented his son his whole life. He just can’t get a break. When you’re like that, it’s: Other people are the reason why I’m messed up.

BJ: I want to step back on this idea of Spike as a cinephile. This is the second quote-unquote war film you’ve made. With this one, I was trying to see the canon of war films, and it was fun for me as a filmmaker to spot things you were doing: paying homage to a few, poking fun at a couple others. Did you have fun making this film?

SL: A lot of fun, but it was hard. Days were rare when it wasn’t 100 degrees plus. We’re shooting in a jungle. Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia mosquitoes ain’t got nothing on Thailand. And jungles have snakes. We had a bona fide snake handler whose job was to keep us from being bitten by venomous snakes. No matter what, we had to do what we had to do.

That was the first time I understood that there was something that had happened to these men that hadn’t been dealt with, that hadn’t been addressed.

Barry Jenkins

BJ: So my first experience with P.T.S.D. was I had an uncle who fought in Vietnam. He went and saw, with a cousin of mine, Return of the Jedi, and my cousin said at about the second reel of the film, my uncle crawled down on the floor and was crouching down behind the seats, trying to dodge the light flashes. My cousin had to cradle him and walk him out of the theater. That was the first time I understood that there was something that had happened to these men that hadn’t been dealt with, that hadn’t been addressed.

When I started seeing clips of Delroy’s performance, I saw my uncle. Before even seeing the film, I started to think, This is why Spike went and made this film. But I wanted to ask you: Why did you decide to make this film?

SL: I’m on Instagram, and so many people have written me stuff that’s very similar to what you just said: that their father, their uncle, their cousin, their brother, they saw Paul, and it made them understand a little bit better what they’re going through.

I was born March 20th, 1957, the first day of spring. The Vietnam War was the first war that was televised into American homes, living rooms. A lot of the footage that is in the film, I saw the first time it was on television. My late brother and I — in Brooklyn, on Saturdays after we finished watching cartoons — we would watch World War II films, and we loved them. My father would say, “O.K., you can like those films, but I’m telling you, Black people fought in World War II.” My father was not in World War II, because he had flat feet, but his two brothers were in the World War. They were in an outfit that drove the trucks to keep Patton’s army going. I was taught early on about Crispus Attucks by my parents. He was the first person to die for the United States of America in the Revolutionary War, Boston Massacre. That’s a fact.

BJ: I love the way you cut to the images of Crispus Attucks. I tried it in Beale Street and got my ass kicked for it a little bit because I think I didn’t go far enough.

SL: People gotta know. I’d never heard of Milton Olive till I started doing research. Brother was 18 years old. Threw himself on a grenade. First African American to get the Medal of Honor in Vietnam.

Crispus Attucks

Photo by Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Milton Lee Olive III

Photo by US Army / PhotoQuest / Getty Images

BJ: Talk to me about working with Delroy after y’all have done so many films together. At a certain point, I grabbed my Oscar in the next room, and I put it in front of the TV. I just put it in front of him. He’s so damn good in the movie.

SL: It’s been 25 years since we worked together. The first time was Malcolm X — West Indian Archie. He played my real-life father, Bill Lee, in Crooklyn, and then he was a drug kingpin gangster in Clockers. He’s one of the great, great, great actors. Delroy has been putting in work. W.E.R.K. Everybody talks about that scene: He’s going into the jungle, chopping down shit left and right with his machete, looking straight into the camera. I’m happy for him because he’s worked a long time and he’s finally getting this shine, getting this light.

BJ: Talk to me about Terence Blanchard. Talk to me about how you and Terence approached the score for this one.

SL: Terence was playing on my father’s scores first. Terence played trumpet in School Daze, he played trumpet on Do the Right Thing. In Mo’ Better Blues, when you see Denzel Washington, that’s Terence on trumpet.

We have a shorthand. We don’t have to talk a lot. He gets the script as soon as everybody gets the script. Once we have a cut, he flies up from New Orleans. He screens the film, then we go for lunch, then we sit down and I tell him where I think I want to have cues. Also, we talk in colors. Every instrument is a different color. And I love to give characters themes with great melodies. Terence has got great melodies up the ying-yang.

BJ: A lot of your films are in this conversation about: What is America, who is America, what is patriotism? It’s interesting, the way these cats [in the movie] talk about it. They’re Black men, I see them, they’re the Bloods. But then to everyone else, they’re G.I., G.I., G.I. It’s the double-consciousness, like W. E. B. Du Bois talked about.

Brother was 18 years old. Threw himself on a grenade. First African American to get the Medal of Honor in Vietnam.

Spike Lee

SL: Here’s the thing, though: I’m very happy when I see people marching all across the world who aren’t Black, chanting, yelling, “Black Lives Matter.” It really makes my heart full to see the young white generation out there doing that. But we have to be taught, because we — Black and white — we’ve just been taught lies and lies and lies. I remember like it was yesterday, our teachers telling us about George Washington. We were not taught that George Washington, the first president of the United States of America, owned 123 slaves. I just found out today Ulysses S. Grant owned slaves. I just found that out today because they tore down a statue in San Francisco.

The foundation of the United States of America is the stealing of land from the native people — and the genocide they inflicted upon the native people — coupled with slavery. That’s how this bitch was built. And it has to be taught, because the foundation isn’t moral, the very foundation. You build a building, the foundation is shaky. Our shit’s been shaky.

This discussion took place prior to Chadwick Boseman’s tragic death.

Chadwick Boseman as Stormin’ Norman

Image courtesy of Netflix