His House writer-director Remi Weekes discusses the making of a haunted-house movie that’s more than it seems with Black List founder Franklin Leonard.

It’s impossible to make a haunted-house movie about Black people.

We’ve been through enough on this side of the spectral plane — or so the logic and joke go — that any indication of a mortal threat from the other side is more than enough reason for us to keep it moving. It doesn’t matter how great our new house might be or what we might have gone through to settle into it.

In that sense, it’s obvious from the opening minutes of Remi Weekes’s debut feature, His House, that the 33-year-old filmmaker has actually done the impossible. The British writer-director has crafted a Black haunted-house movie that never makes the audience question its inhabitants’ Blackness — despite their sticking around in the face of very real danger. Very simply, the consequences of leaving are worse.

Husband and wife Bol and Rial — played by Sope Dirisu (the Nigerian British actor whose credits include Gangs of London) and Nigerian-born Wunmi Mosaku (Lovecraft Country), delivering star turns that are both naturalistic and highly technical — are refugees of South Sudan’s civil war. If they leave the resettlement quarters they’ve been gifted by Her Majesty’s Government, they’ll be swiftly returned to the violence they risked life and limb to escape. Yet, as they soon discover, that might be preferable to sticking around with whatever has joined them in their new home. Such is life for a refugee in the 21st century.

It’s a bold debut from Weekes, who previously wrote and directed the short film Tickle Monster, which made its U.S. premiere at South by Southwest in 2017. His House is a horror film about survivor’s guilt, about home and its myriad definitions, that is both impossible and impossibly vital as the worldwide refugee crisis escalates with no end in sight.

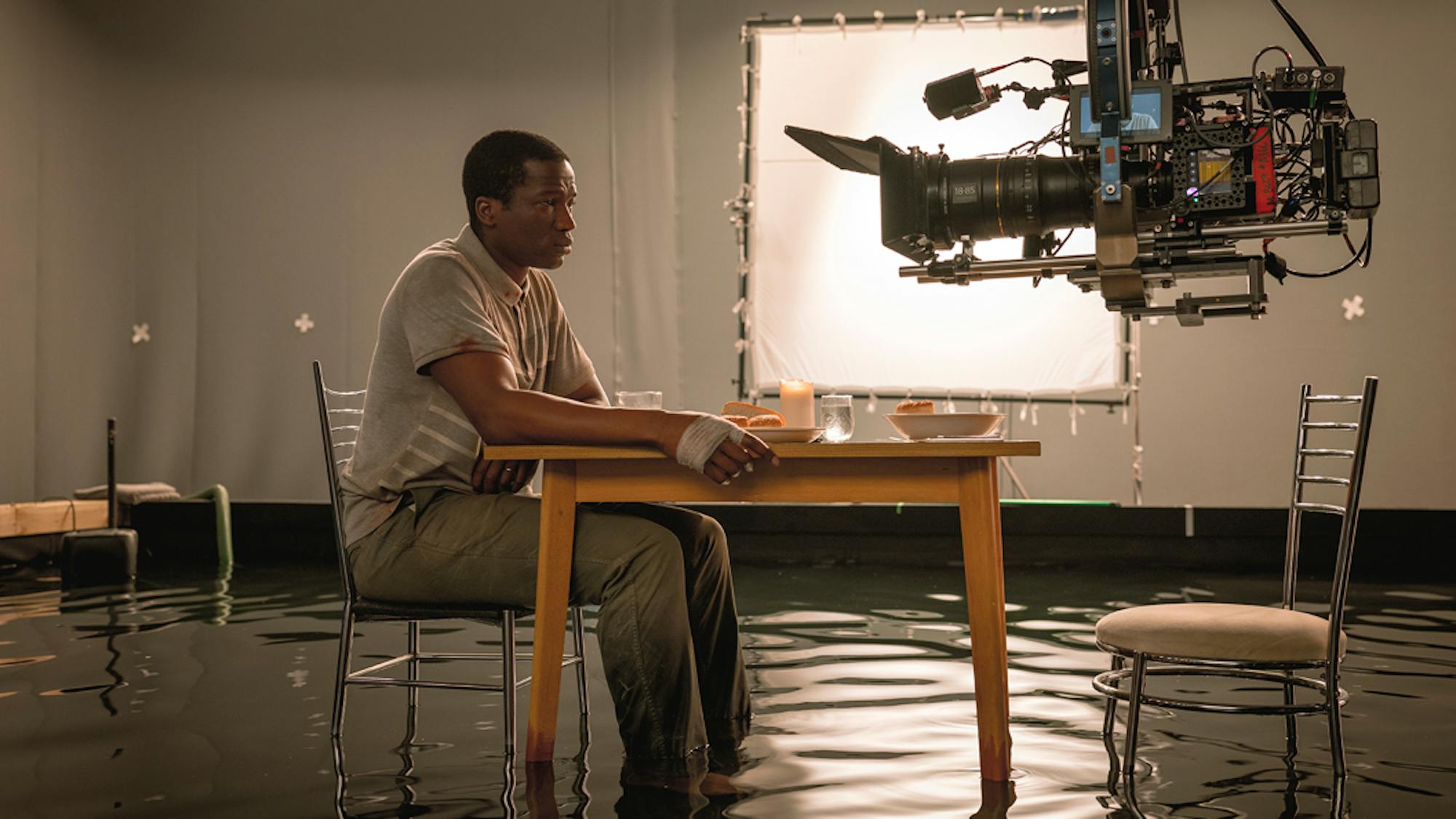

Remi Weekes on the set of His House

I spoke with Weekes about why and how he made His House.

Franklin Leonard: There is a classic 1982 bit by Eddie Murphy about how you can’t have horror movies with Black people, about how that movie would just be like, “Wow, baby, this house is beautiful. We got a chandelier hanging up here, kids outside playing. I love it.” Then there’s a demonic whisper: “Get out.” The response is: “Too bad we can’t stay!”

With this film, you created a haunted-house film with Black people, and it works. Walk me through how this story came to be a film.

Remi Weekes: The film was based on a lot of research about the immigration process in the U.K. One of the strange things that happens in the U.K. is that once you become an asylum seeker, you are often given an accommodation to live in. However, you’re also given really draconian rules to live by. One of them is basically: You’re stuck in this house and that’s it. You can’t even get the luxury to decide, Oh, actually this house is haunted, so we need a new place. I found that quite fascinating — especially, as you say, because one of the big things about horror films is that if you know there’s a ghost hanging around your house, why are you staying?

My family is from all over the world. The communities I grew up in are diverse, and the U.K. is not particularly comfortable with the idea of diversity. Part of you wants to try to assimilate, but then there’s this other part of you that wants to stick your middle finger up and say, “I’m proud to be who I am.” Those sides of you are always tussling with each other. When telling a story about people who have arrived to a new place and are trying to move on with their lives, I found it interesting that two people could have these opposite perspectives. I thought the drama of the piece could be about the conciliation of those two feelings, against this haunted-house setting.

If you're within the culture long enough, white supremacy soaks into everything.

Remi Weekes

There are really exceptional performances from the stars, Sope and Wunmi. How did you find them? This is essentially a two-hander, and these are not easy roles.

RW: They are both amazing and beautiful actors and human beings. When you’re about to make your first film, there’s always the anxiety that you will be overwhelmed and you’ll be the amateur among professionals. It could all go wrong so quickly. I was so fortunate that I was able to work with both Sope and Wunmi. We were casting for a good while all over the world, and by some serendipity, they were both able to come around the same time and audition together. They also knew each other vaguely, so the chemistry was easy. It was clear in a moment that they would work out.

When it came to developing the roles and performing on camera, they were so different in terms of their technique and the nuts and bolts of how they created the performance. The way they get to an emotional truth, they’re excellent.

Wunmi Mosaku and Sope Dirisu as Rial and Bol

Both Bol and Rial say the same line in one form or another — this notion that they are “one of the good ones.” As a Black American, that struck at the core of my own experience.

RW: I’m sure it’s similar everywhere, that notion of the good immigrant and the need to be accepted into the culture, always being judged on a level much higher than anyone else is judged on.

I love when Rial chastises Bol and says, “You still idolize them. You thank them for their unseasoned scraps.” I specifically want to talk about the choice of the adjective “unseasoned,” which I thought was a remarkable bit of detail from a screenwriting perspective.

RW: I think for many people who try Western food, it’s amazingly unseasoned, especially when you’re from a warmer region where the food’s really delicious. You get here, and it’s not the nicest, and it’s confusing.

It's not always going to be easy, but that's part of being a whole person, a whole society, a whole country.

Remi Weekes

There was another beat that I clocked immediately. Upon getting out of detention, upon getting their house, the first thing Bol does is get a haircut. It felt like such an explicitly Black moment. I think any Black person — even one like me who hasn’t had a haircut in over 20 years — would recognize it as such. Could you talk about the articulation of Blackness in the context of this movie? At one point, Rial is lost and she’s mocked by these Black teenagers.

RW: Whether it’s African or Caribbean or whatnot, it’s amazing how even amongst ourselves, the ideas that come from these Western and white notions of Blackness seep into our culture sometimes and create divisions. It can be sad.

All the moments in this film are based on research. That scene with Rial talking to the group of kids was partially inspired by some stories that I’ve heard wherein immigrants come to either the U.K. or to America, and they suddenly realize that even to Black Americans or Black British people, they’re still seen as immigrants, they’re still seen as Africans or “lower than.” It confuses them. They almost feel like a brotherhood has been split in half. Part of that is a divide-and-conquer tactic based on white supremacy. If you’re within the culture long enough, white supremacy soaks into everything.

Did you seek out South Sudanese immigrant communities and speak to them directly? How did you approach the research process?

RW: There was research in terms of reading and collecting articles and in terms of interviews. It’s not just about South Sudanese immigrants, but also about the system in the U.K.: For example, what happens to asylum seekers once they get out of detention centers? It’s also about the journey — the journey from Africa to Europe and the U.K. We had a university lecturer from South Sudan who came on board and helped us to get the references and the design right, and to bring on other people to help with that.

You made a number of directorial choices that were explicitly non-naturalistic. There’s the moment where Bol is eating dinner and you pull back, and you realize that you’re in the ocean. There are moments where Rial wakes up and realizes she’s not where she expects to be. How did you build those into the script and then execute them on the day?

RW: So Bol eating dinner in the kitchen, that was always scripted, but it was originally written in multiple cuts. We cut to him eating, and then to the knife and fork, and then back out. Through the cuts, we slowly revealed that he was in the ocean. When it went into production, I must’ve had one of those moments like, Oh, actually, wouldn’t it be cool if it just tracks out? Like he doesn’t even notice what’s happening, and the camera’s not making a big deal of it? It’s just really downplayed. I think part of that is because before I made the film, I was part of a directing collective, and we made very fun, visual, artsy short films. We would always find borderline dull ways to photograph things that were quite spectacular. I like that contradiction. I like thinking of ways I can make a spectacle but be very normcore about it.

Sope Dirisu as Bol

Did you build the house on a soundstage? How did that come together from a craft perspective?

RW: We shot on location to begin with, in a neighborhood called Tilbury, in Essex. We found the house that we wanted to set the film in, and we shot a week there. Then we recreated the house on a soundstage in West London. It was really fun using the soundstage — with the moving walls, and the ability to put things behind the walls and mix things up a bit.

One of the last lines in the film is: “Your ghosts follow you. They never leave. It’s when I let them in, I could start to face myself.” There are obviously ghosts in the context of the film, but what other ghosts do you see in the world?

RW: I think what that moment is about is, even though there is some ugliness, it’s O.K. to let the ghosts of your own past in. There’s trauma, but there are also beautiful things, profound things. You can view so many social things happening in the U.K. and the world at the moment through this lens. A conversation that’s happening right now in the U.K. that is overwhelming to talk about is the role the slave trade has played in society. I think it’s really important to look at your past, even the ugly stuff, and to acknowledge and think about it. It’s not always going to be easy, but that’s part of being a whole person, a whole society, a whole country.

A peek behind the scenes of His House