From the streets of Chicago to a classic Sorkin courtroom, the cinematographer captures the action for The Trial of the Chicago 7.

The Trial of the Chicago 7 was “conceived in Aaron Sorkin’s mind when he first sat down to write the script,” says Phedon Papamichael, reflecting on his work as the film’s director of photography. “My job was to get as close as possible to that vision and bring it to the screen.” The historical drama, which Sorkin also directed, chronicles the antiwar demonstrations at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, their deterioration into violent clashes with authorities, and the trial of protest organizers that followed. Papamichael’s contributions as cinematographer have earned him his second Oscar nomination.

Over the course of his career, Papamichael has collaborated with an impressive list of filmmakers, including James Mangold, Alexander Payne, Oliver Stone, and Wim Wenders. He earned his first Academy Award nomination nearly a decade ago, for Payne’s Nebraska; he also worked with the writer-director on Sideways, The Descendants, and Downsizing. His long-running collaboration with Mangold includes Walk the Line, 3:10 to Yuma, and 2019’s 1960s-set racing film Ford v Ferrari, which, like Chicago 7, was inspired by real events.

For Sorkin’s drama, Papamichael turned to period lenses to transport viewers to the late 60s, using a large frame with a custom combination of anamorphics: ARRI Alexa LF, Mini LF, and Panavision lenses. He used handheld photography to capture the chaotic scenes on the streets of Chicago, and employed three cameras to cover the courtroom sequences in more composed shots. For the finale, when the defendants hear the verdict — and activist Tom Hayden (Eddie Redmayne) honors the lives of the soldiers lost in Vietnam by reading out the names of the fallen — Papamichael set out to magnify the triumph. “When the [actors] came out in their white prison outfits, it gave me an opportunity to hit them with a harder sunbeam,” he says. “When Tom Hayden stands and reads the names, he glows as this heroic, angelic figure, and the whole courtroom stands.”

Phedon Papamichael frames a shot of the Chicago Field Museum for The Trial of the Chicago 7

Queue spoke to Phedon Papamichael about what went into photographing The Trial of the Chicago 7.

Queue: How did you find the experience of working with Aaron Sorkin?

Phedon Papamichael: He has a very precise vision of how he wants to see things. He understands the significance of shots without having to really express it technically. It was great for me to be able to find that for him and see his reactions. I’ve worked with Alexander Payne and other writer-director, auteur filmmakers. Sorkin is so in his head in a way, so precisely formulated — similar to Alexander Payne when an actor wants to change something. I remember on Sideways, Thomas Haden Church wanted to change one line. Alexander thought about it for 30 seconds and he goes, “Let’s stick to the screenplay.” It’s something he’d thought about, this word, for six months. Aaron’s the same. There’s a reason it’s this word and not that word.

Once you discover the precision of the thought, that applies to the visuals also. It becomes very efficient. You realize, I really don’t need to be wasting my time on this wide shot or on this coverage or this reaction shot, and that’s great. I hate being wasteful. He gave me a lot of freedom in terms of all the lens choices, the setups and stuff, but I was also very conscious of what he wanted.

So much of the film takes place in the courtroom. How did you approach filming that set?

PP: We had a lot of control on our set, so there’s a lot of diversity in the looks that we created in the court — sunny days, overcast days, rainy days — and how they interact with cutaways. You know, the warm, sunny scenes cut to this extreme dark, moody scene.

We had a lot of characters to cover. The defendants are seven, and you’ve got the lawyers, you’ve got the judge, you’ve got the jury. We knew that we would take a more composed and static approach to a lot of it — with some exceptions — and then save the more energetic camera and the handheld camera and apply that to whenever we were outside the courtroom where we have a lot of movement. All the Chicago riots really have that energy from Haskell Wexler’s feature film Medium Cool. We did handheld, and it has a very different energy in terms of the framing and the compositions. Since we’re intercutting, it’s really a nice juxtaposition to the visual spheres of the movie.

Aaron Sorkin and Phedon Papamichael on the courtroom set

How did the film’s period setting influence your approach?

PP: I shot on some of the same lenses I had experimented with in the past — sort of period glass. It’s anamorphic. I used a large-format camera that really creates a different falloff and natural vignetting on the lenses. All of that really helped with the period. The Panavision anamorphic set needed to be customized and expanded, and that was done by Dan Sasaki, the lens guru of Panavision. You can affect how warm the glass is, how the flare characteristics are, how much falloff and softness you want on the edges. That was something we could really dial in nicely. I had some experience because I’d just used some similar lenses on Ford v Ferrari, my last film, and that was also set in ’66, ’67. This is almost a continuation of the time period. Very different kind of film, of course, but it was nice to have some experience with that particular glass that really helped take the modernness off the image.

What about the other key locations in the film? How did you approach shooting on the other sets that production designer Shane Valentino created?

PP: This old house that they’ve taken over and converted into a “conspiracy center,” that was a great set. The conspiracy office was very rich, very dense, with lots of wood. The set design and set dressing were so rich in terms of all the little details. It’s a very busy place, but also warm and cozy. We spent five days in there, and it has a warmer look at night. It has these old, beautiful tungsten practicals from the period. We really embraced that.

We also had the Black Panthers headquarters. People still smoked cigarettes back then, so we could get away with applying cigarette smoke for some atmosphere, which I normally don’t do. The judge’s chambers, the various offices, the attorney general’s office, they all have their own color palette. There’s a specific warmth or coolness or saturation or texture to each individual place. You try to find a balance to have these pieces that will come together. It gives you so many possibilities to apply different looks and still have this through line and really tell the story visually and support the writing.

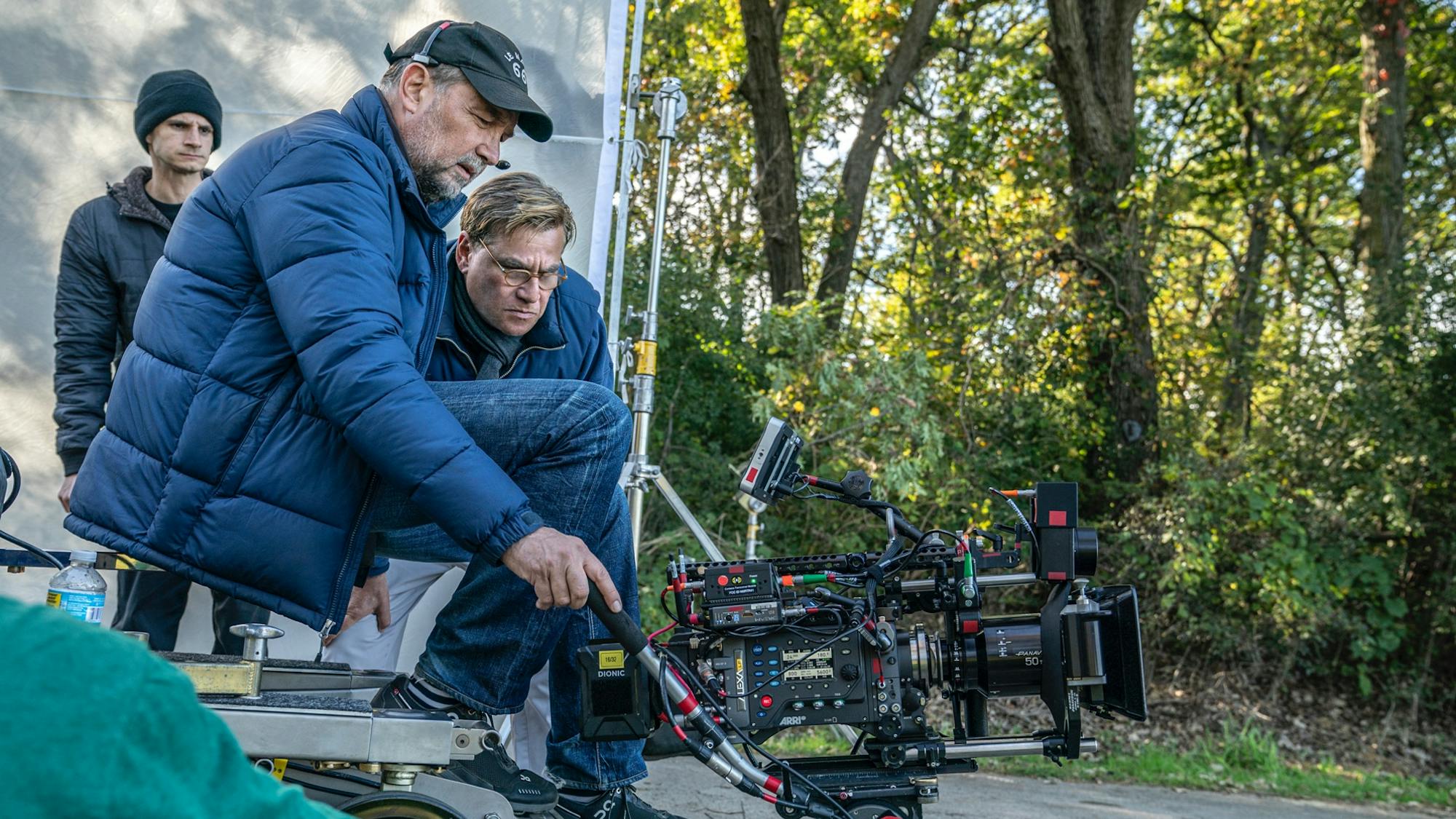

Phedon Papamichael behind the scenes

Working with a large ensemble of actors of this caliber, was it challenging to focus on one or more of them to the exclusion of others in certain scenes?

PP: They are a tight group, and there are lots of moments where they are all interacting. Those were wonderful. I did shoot multiple cameras on this more than I normally do. Normally I take the approach that there’s one perfect angle and the second one is slightly compromised. But in this case, it really made a lot of sense and we wanted to give people the freedom to be able to overlap and keep the cameras rolling. We designed some shots that carry us from one situation to another, from one character to another — walk and talks or handoffs. But in the courtroom, because everybody is very static — they’re in their assigned seats every day — I used three cameras on a regular basis. I could have used four or five.

Phedon Papamichael works on a night shoot in Chicago’s Grant Park

How was it to shoot in Chicago?

PP: The great thing is we’re shooting at the actual historical location. You can’t do better than that. We shot in Grant Park and in front of the Hilton. We looked at photographs from the 60s, and amazingly enough, little had changed. Of course, there were some new buildings we needed to avoid or fix a bit in post-production. But it turned out that we had to do very little — just embrace the actual locations, the statues, the bridges.

There were a lot of elements to play with visually: the police, the riot gear, the tear gas. We could get pretty stylized and still keep it realistic. Whenever you’re recreating history, you want it to be cinematic, but also, in this case, I didn’t want it to be too stylized. I wanted to give it some of that actual rough energy that a lot of a documentary footage that I had seen and researched had. Being at the actual place was fantastic.

Phedon Papamichael with Aaron Sorkin on set