The director of Oscar-nominated The Hand of God takes us to the Naples of his film and of his memories.

The City

Naples is a city where the people who you meet, they help you a great deal to tell stories; this is because everyone claims their own uniqueness, their own singularity. Most people invent characters for themselves, exceptional stories, and so it is very helpful to live here if you want to tell stories.

When I made a film set in Switzerland, I knew perfectly well which sounds I had heard in Switzerland because I went there with a different attention. The truth is you take no notice of the place you live — it is a place that for you is natural. When I made The Hand of God, I struggled to remember things about the city. I had to reconstruct the sounds. Naples is a noisy city, of this there is no doubt. The noises that I remember and that I tried to put in the film are the voices of the people on the balconies. In Naples, there is a lot of calling: mothers calling their children from the balcony, children who call their mothers from the street. When I was a boy, it was continuous, the sounds of people calling other people. And then there were the noises that were part of my adolescence, like the sound of the mopeds; I remember those well.

It is true that the city changes little, or changes less than other cities. This is reassuring on one hand, but on the other, new things are also part of the beauty of life. It is a city that knows how to adapt to the outside but never denies what it is and, ultimately, this is very beautiful. Those who have lived in a city since birth end up paying little attention to the aesthetic aspect of the city; you don’t notice the beauty or the ugliness. To come back to Naples for me is to come across very powerful things, encounters with the utmost joy and the utmost pain. It’s all here.

The Shop

I didn’t come here with my family; this is a place I discovered alone as a boy, because I come from a district in the upper part of the city, Vomero, which is a kind of island in its own right, and so for me this place represents discovery, adolescence, when I started to stick my head out of the small district where I used to live.

I like the shop very much because it is a mixture of the sacred and profane, which, in the case of [Diego] Maradona, was not even that profane because, in reality, you can only understand Maradona through the relationship with the divine. Maradona represented, for a population that had always been a little cast down, the possibility of being exceptional. He was someone about whom little was known; he was someone who woke us up, especially the kids of my generation. He was like a bolt from the blue.

Maradona did not arrive in Naples, he appeared. He was different; that is to say, he was a figure with a very close relationship with the divine, who found fertile ground here because it is a city in constant dialogue with the divine, in its own way. So Maradona came to the perfect place to establish a myth that has to do with football, but has to do more with religion. Everything that happened to Maradona always seems like a reflection of what can happen to religious figures. His success was the reverse side of the coin of tragedy. So the immediate representation that came to the minds of artists was to give him wings once he was dead.

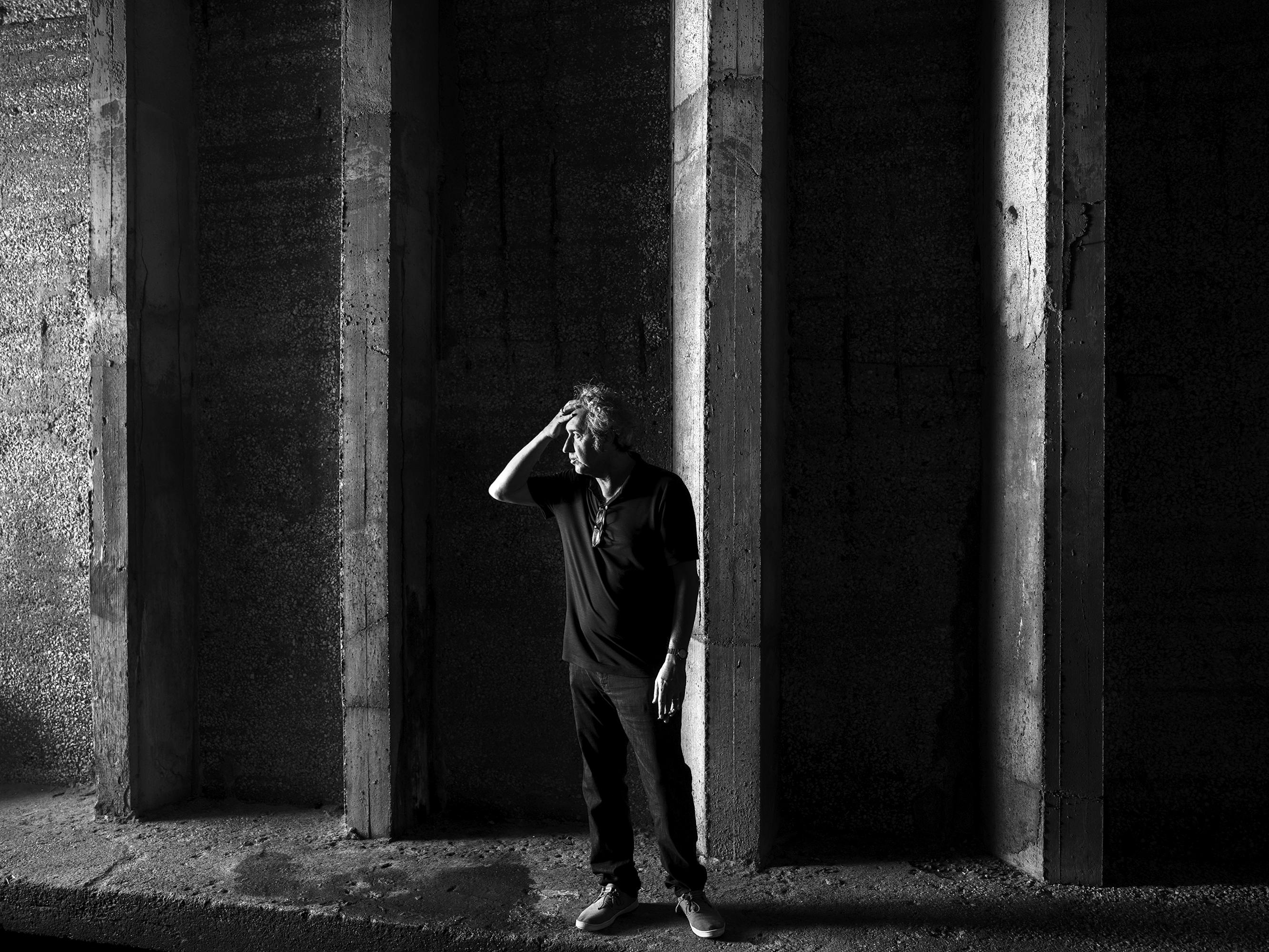

The Cave

This place, where one of the final scenes was shot — the key scene between Fabietto and [Antonio] Capuano — is a little like a synthesis of the city, that is, a place that leads from closure to opening. This place, as well as being undeniably beautiful, has this outlet, this possibility of opening up. With one pace, you can reach the sea. It is rather symbolic, the fact that from a situation of such withdrawal, of suffering, in an instant you can find a future. I decided to shoot here because there was a relationship between closed and open, and because it is simply a beautiful spot with beautiful light. In reality, the decision to shoot in one place rather than another is dictated by the fact that in certain places I see images, in other places I don’t see them. Here, I saw them all.

The Home

Here is where I lived for 37 years, from birth to the age of 37. I used to live on stairway C, on the fifth floor, and I shot the film here, in a house similar to mine, on the floor below. The experience of returning here, after so many years when I didn’t come, has been strange. It’s not easy to find the words to explain the encounters with memories; they are difficult feelings to put into words. It has been emotional. 37 years is a very long time, but a few minutes after I got here, it was as if I had just left. I remember everything, everything, everything.

Growing up here was wonderful because there were many of us children. It was very peaceful, comfortable, reassuring; we were free because there were no dangers. We played football and various games. The tree is still here that we used to climb. There was a wonderful basin with a fountain at the center where we joked around, we splashed about, rather like in the [Terrence] Malick films when the children play. All in all, I have wonderful memories and, of course, I also have some unpleasant memories. That’s how life is.

It is very emotional even if, in reality, I came here to work and so, in the end, the aspect of working takes the upper hand. And so, you work and you forget things. Perhaps I also tried not to get too emotional because I had to make a film and, to make a film, the emotional dimension has to be put aside, otherwise you make the wrong decisions. I managed to force myself not to give in too much to memories, because you idealize memories when you are far away; when you come closer, they become less powerful. I simply portrayed the Naples I knew, which was very far from the Naples of the historic center. This is any little middle-class area that happens to be in Naples but could be in any city in Italy, which was always very like this, very quiet, very calm. Thinking back, it seems strange to me that so many stories and so many characters came to my mind, concerning a place where practically nothing happens.

I think that Fabietto had to leave Naples because in Naples tragedy was simply built into his life, and tragedy has a temporal duration that can be borne only within limits. At a certain point, you have to flee, and flight is a very ancient remedy for escaping tragedy. Changing places is very helpful. He knew a joyous city through the joy of his family, and then later he knew a sorrowful city because his private life was sorrowful, and so leaving is the remedy that many people adopt to try to deal with, to escape sorrow.