Production designer Maria Djurkovic recreates the archeological discovery of a lifetime for The Dig.

The air is crisp, filled with dimming light from a cloudy summer sky. The Dig is unhurried in this moment. A small team marvel at what they’ve discovered in the ground beneath their feet. It’s almost too remarkable: a great ship, its origins in time as yet unknown.

Of course, the stern they’re looking at doesn’t belong to a real ship. The real ship’s burial site is miles away, in Sutton Hoo, Suffolk. Standing over the stern are not archeologists but actors. They’re staring at an intricate and meticulous recreation built in Godalming, Surrey, just outside of London.

The real site’s footprint is much larger than just a ship shape in the sand. In 1939, landowner Edith Pretty and archeologist Basil Brown began digging beneath a series of burial mounds in Sutton Hoo. What they found changed our understanding of Anglo-Saxon culture, showing archeologists that the so-called Dark Ages in Britain were home to a more complex and sophisticated culture than previously known.

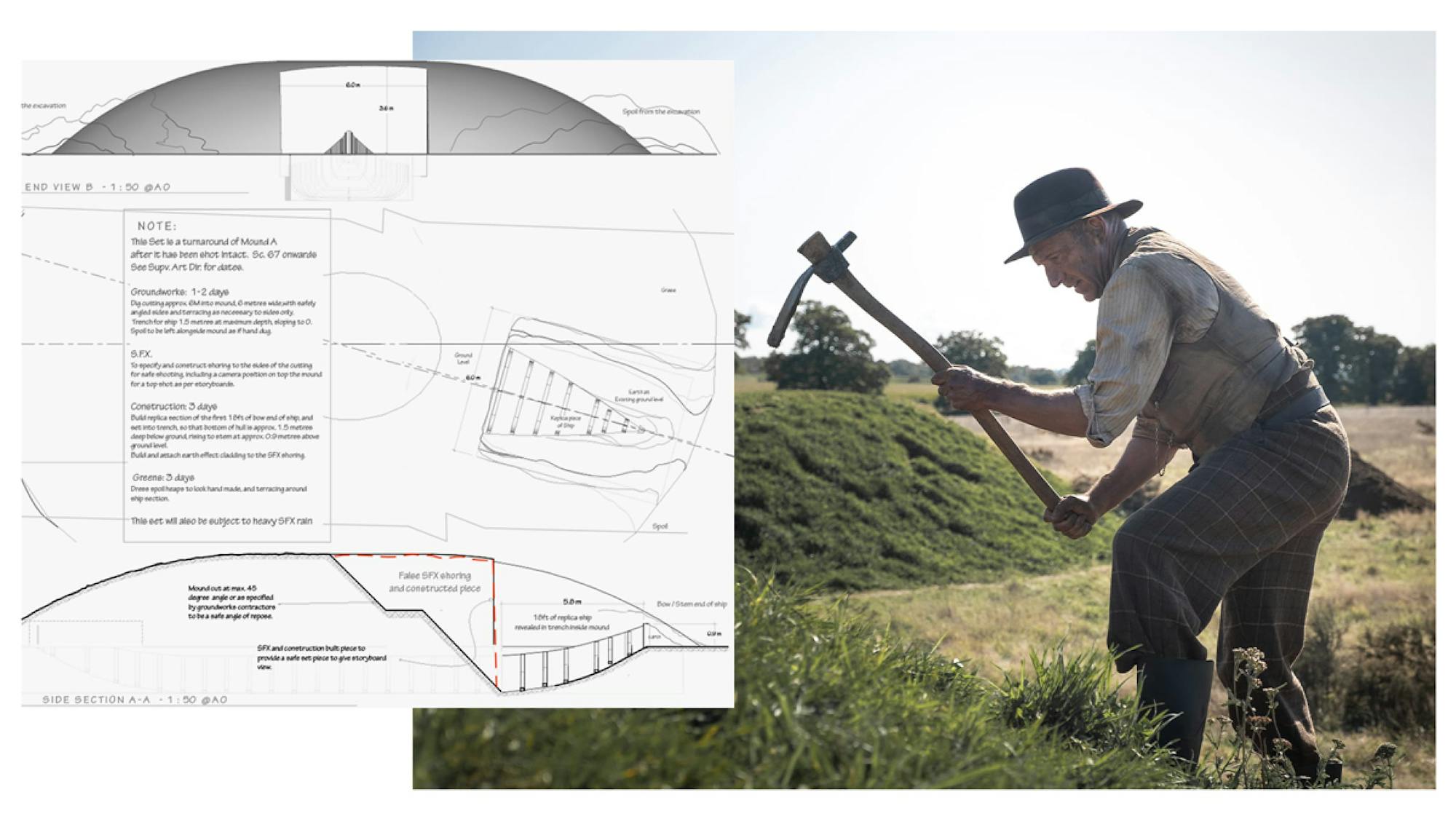

Basil Brown (Ralph Fiennes) at one of the ancient burial mounds

Among the many artifacts discovered were silver and gold pieces that came from around the world, indicating that the Anglo-Saxons were not cut off from their neighbors, but routinely traded with them. Still, the most breathtaking find was an 89-foot ship containing a burial chamber filled with treasures, including an ornate iron helmet, one of the most significant Anglo-Saxon artifacts ever uncovered.

It’s Pretty and Brown’s story — in the hands of actors Carey Mulligan and Ralph Fiennes — that’s told in The Dig, director Simon Stone’s drama feature based on the historical novel by John Preston. And it’s The Dig’s production designer, Maria Djurkovic, who was tasked with reconstructing the form of the ancient ship, the earth compressed around its silhouette.

“In reality, it wasn’t even a tangible object,” she explains of the real vessel. “I can only describe it as an imprint. The only concrete things that remained were the iron rivets.”

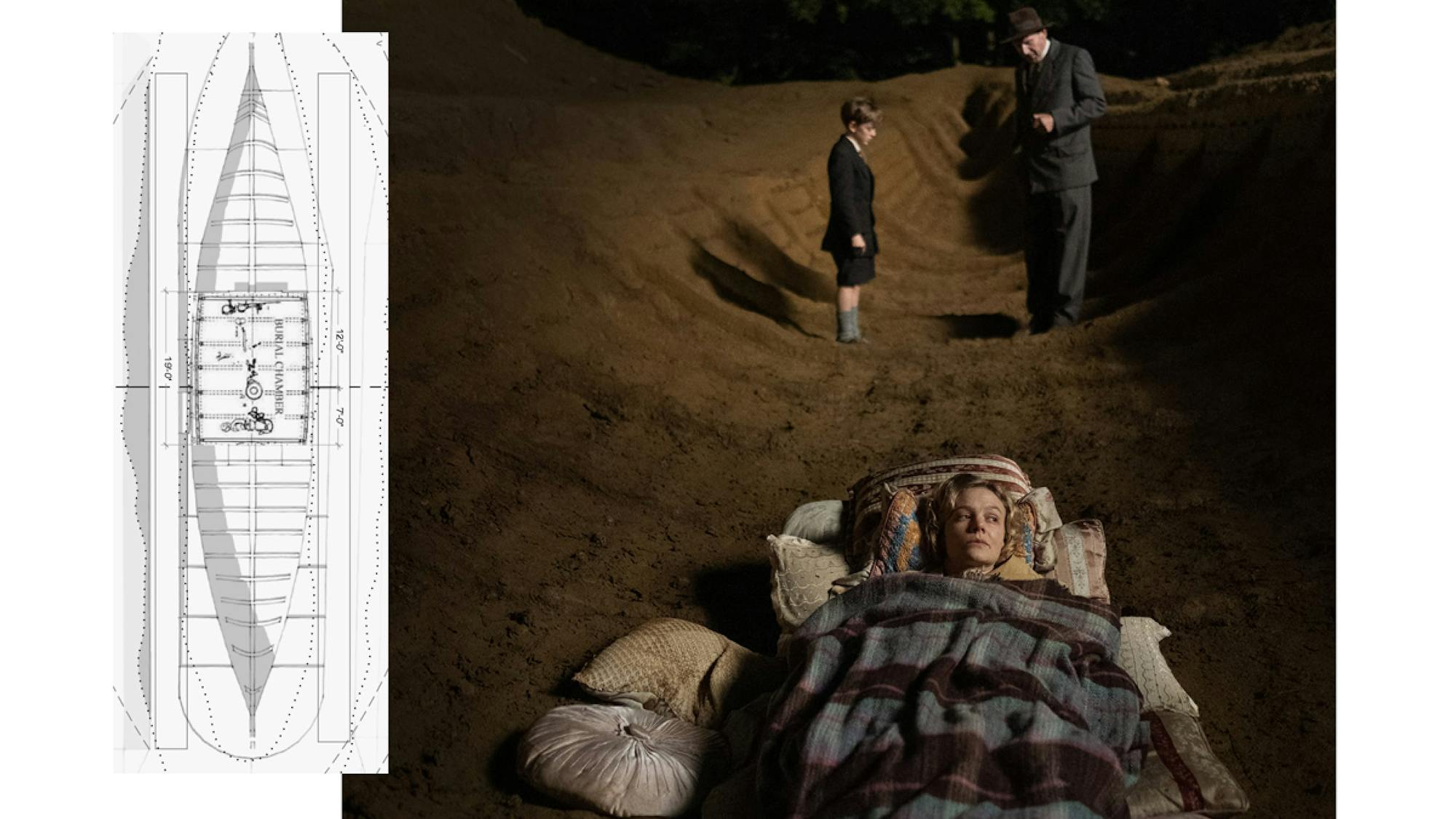

Edith (Carey Mulligan), her son, Robert (Archie Barnes), and Basil (Ralph Fiennes) at the dig site

She and her team proceeded to build their set on a schedule such that the actors and crew could work in long takes and reset if necessary. Add in the fickle English weather, and it all added up to some serious practical obstacles. But the production designer was never tempted to flee to a studio.

“This was so elemental. It was all about being in the landscape,” she explains. “The artificiality of a studio would have been completely wrong.”

Djurkovic believes in providing a strong visual identity for all the films she works on. With The Dig, that core inspiration came from the Sutton Hoo countryside: huge skies; a wide, flat horizon stretching out to the furthest distance; a delicate color palette. This landscape provided more than the basis for the actors’ “dig site.” It influenced the costumes and the houses that the characters wander through; it informed the way the director framed his shots, grounding his subjects low in the frame.

Edith Pretty (Carey Mulligan) wanders through the yellow fields of Sutton Hoo

“Maria is extraordinary. She has such a skill of finding the cinematic elements of a particular location,” Stone reflects. “No one has created a film like this before. During pre-production, we couldn’t go and watch all the archeology films for reference. You have Indiana Jones and very little else.”

As Djurkovic and her crew set about reshaping a field in Godalming, Surrey to mimic the real site in Suffolk, they brought in tons and tons of dirt to replicate the mysterious mounds under which the ship lay untouched for hundreds of years. In late summer, the team covered the mounds in turf and meadow seeds so they would start to blend in as the seasons passed. But by fall, the plants had grown too green compared to the rest of the yellowing field. Djurkovic enlisted painters to go through and correct the colors, while she set about carving fake rabbit holes into the hillsides.

It was an immensely complicated process, but one that Djurkovic almost brushes over when she compares it to the true challenge: constructing the historical ship. While the first half of The Dig was shot largely sequentially, the back half (once the ship is uncovered) was shot almost entirely backwards, with the production-design filling in the set as it went along.

“If we had built the ship and then covered it with tons of earth again to recreate the mounds, the weight of the earth would have been far too much for our set,” Djurkovic says. “So we created the excavation, and then we started working in reverse.”

Basil (Ralph Fiennes) makes his way through the digsite with Robert (Archie Barnes) in tow

The ship in The Dig was not quite as delicate as its inspiration. It was created with plaster, timber, and cement. All the same, the set was a constant battle against the elements. While the team avoided torrential floods, there were still some “soggy mornings” that required crew members to bail out water. Even on good days, dirt was constantly being shoveled out by actors and then put back in by production. Mud was everywhere. And Djurkovic and her team were always working to make the ground look like it hadn’t been trampled by hundreds of crew members and their equipment.

It was a far cry from where Djurkovic started her research, nestled cozily in the British Museum, studying every picture she could of Sutton Hoo. The museum ultimately trusted the crew with real artifacts, which were buried in the dirt for the actors to find (a day that Djurkovic says made the prop master “very nervous”).

As they work their way into the ground, the characters in The Dig are pulling at the strands of history — some of it buried deep, so to speak, and some of it forming around them — and they ponder what it means to endure in this world. It’s a question that Djurkovic herself wondered about, watching the dirt pile up on her painstaking work until the ship was no longer visible.

“I’ve always loved history, and recreating periods of history that are no longer,” she says. “It’s about finding the character, the layers of life. And the funny part is that in the final bit of the movie, when you see Basil literally shoveling earth back into the hole, we sort of had to do that too. It was as if we had never been there.”