For his muscular new thriller, David Fincher worked with many of his closest collaborators to develop inventive approaches to the film’s cinematography, editing, sound, and score.

Cinematography

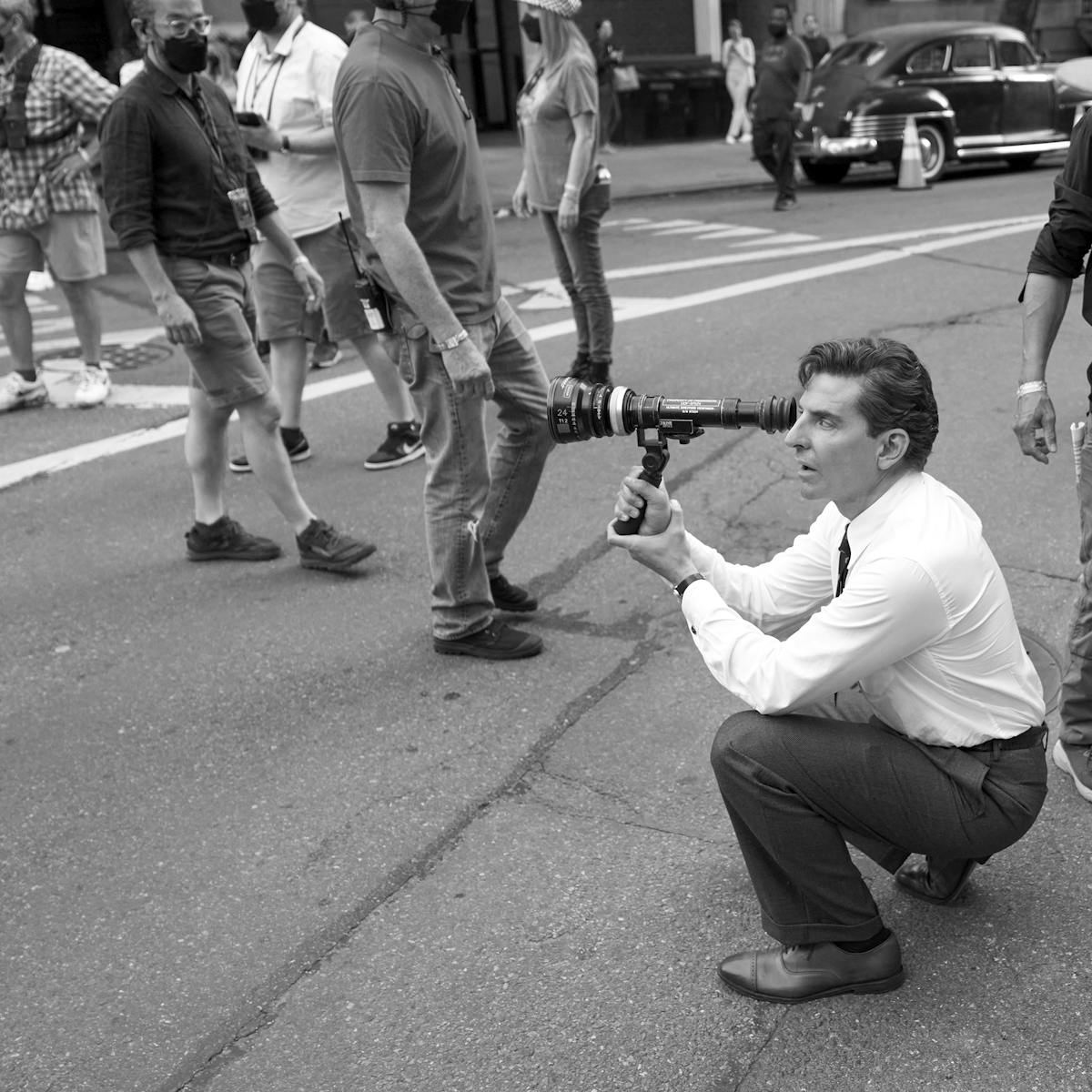

Erik Messerschmidt

As established in the gripping Paris-set opening sequence, The Killer, played by Oscar nominee Michael Fassbender, is self-assured, patient, and methodical. He passes the hours waiting for his target inside an empty WeWork space, musing to himself in voice-over, repeating the rules he lives by — his professional code — like a mantra. “The movie is about process and procedure, and someone who thinks they’re very much in control of their own world,” says cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt, who won an Academy Award for his previous film with Fincher, 2020’s black-and-white Old Hollywood epic Mank.

Together, Messerschmidt and Fincher designed a visual language to differentiate scenes rooted in The Killer’s vantage point from moments when the audience is watching the story unfold from a more objective perspective. For subjective scenes, the cinematographer employed longer lenses to suggest that the character has “almost superhuman vision,” says Messerschmidt. “He’s able to observe things from afar.” For the objective scenes, Messerschmidt used wider lenses and more structured compositions. “We’re always six or eight feet away from him,” he says. “[The audience is] this omniscient ghost watching him go through this process.”

“What was very important to us was that the locations felt distinctly different, that the audience had a sense of the shift in climate, the change in light quality, the change in The Killer’s experience in [these] places,” Messerschmidt says. “Paris, to me, always feels blue. The Dominican Republic is hot and humid and wet. New Orleans has a similar type of heat and humidity, but it’s slightly less tropical. We tried to find a palette that matched the locations where the character was.”

The Dominatrix (Monique Ganderton) and The Target (Endre Hules)

Editing

Kirk Baxter

Despite The Killer’s whirlwind tour of some of the globe’s most glamorous locations, the film is designed to focus on the daily grind of what the job would really be like. “When I read this screenplay, it shows at great length the practicality of execution, of taking care to not leave D.N.A.,” says editor Kirk Baxter. “It’s not just kicking down doors or running across the top of trains.”

Having won two Oscars for his work on Fincher’s films The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011) and The Social Network (2010) and earned a nomination for a third collaboration, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008), Baxter had a long-established rapport with Fincher that enabled him to home in on what stylistic options would appeal to the filmmaker.

For the Paris sequence, Baxter sought to underscore the patience and precision required by The Killer to carry out his task, which appears to be entirely on track — until a stray bullet misses its intended target. “It was this very considered, meticulous thing,” Baxter says. “It’s the long taffy pull, the suspense in it. Everything’s very even until it’s not going according to plan, and then we get to flip that. I really got to play with pace and presentation of information. When things aren’t in his control, the camera gets handheld. I start to jump-cut action a little bit, and it becomes more chaotic.”

Baxter often takes his editing cues from The Killer’s voice-over, which allows the viewer to hear the character’s internal monologue. “It’s more an internal musing,” says Baxter, “He’ll be talking to himself, not necessarily to us. If something comes in that’s [not part of] his plan, he doesn’t get to finish that sentence. That helps telegraph that we’re getting his inner thoughts, and they’re a bit jumbled. You feel like you’re getting this inside scoop. It’s not an instructional voice-over like the voice of God that often comes with movies.”

The Killer (Michael Fassbender)

Sound

Ren Klyce

Very little is revealed about Fassbender’s character — no information is shared about how he came to be an assassin, the body he works for, even his name. But we can glean from his listening habits that his favorite band is The Smiths, the 1980s English outfit that married comically macabre lyrics with jangly guitar chords to deliver pop music that has endured for decades. The roughly 12 Smiths tracks featured in the film include some of the group’s most immediately recognizable songs — “Girlfriend in a Coma,” “Shoplifters of the World Unite,” and “How Soon Is Now?” among them.

“David really wanted to make it seem like any time Fassbender’s character was going to kill somebody, he’d have his ‘work playlist’ on his iPod,” says Oscar-nominated supervising sound editor Ren Klyce, who has worked on almost every one of the filmmaker’s features. Although he and the director experimented with other options — classical music, Dusty Springfield, post-punk icons Siouxsie and the Banshees — none of them proved as ideal as The Smiths. “The Smiths give you an insight into what his aesthetic is,” Klyce says.

Fincher asked Klyce to take a “documentary approach” to the film’s sound, to ensure that the audience heard what Fassbender’s character would hear. “Every time we’re inside of the guy’s head, we’re hearing the world from inside of his head,” Klyce explains. “When we’re outside of his body, you hear little tinny iPod speakers like you would if you’re lying next to somebody, and you can kind of hear the music. But when we are looking through his eyes, then we’re hearing that music fully, in full fidelity, as if we are him listening to his earbuds.

“In fact,” Klyce adds, “there were some scenes where The Killer only has one earbud in his ear, and David said, ‘Okay, I don’t want to hear the music,’ or, ‘I only want to hear that loud music on the right, because it’s coming out of his right ear.’”

The Killer (Michael Fassbender)

Score

Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross

When Fincher spoke to Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross about what he was looking for with the score for The Killer, his brief to the Oscar-winning composers of The Social Network was simple: “It needs to be very antisocial,” recalls the filmmaker. Fincher hoped their music would serve as the emotional barometer for the protagonist, in addition to ratcheting up the unsettling tension in certain scenes.

The duo was more than up for the challenge. While working together in Reznor’s iconic alternative rock group, Nine Inch Nails, the pair had long since mastered myriad ways to make moving, antisocial music full of sorrow and angst and blasts of furious emotion. As composers, they’d proven their originality and versatility not only on Fincher’s 2010 Facebook drama The Social Network, but also on several of his other productions including Mank, Gone Girl, and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo — not to mention their numerous collaborations with other highly lauded filmmakers. “I just love it when they go to town to make the hair on the back of your neck stand up,” says Fincher of Reznor and Ross.

The film’s memorable, moody score was yet another way to put the audience in the same frame of mind as Fassbender’s unconventional antihero. “I liked the idea of exploring the inner psyche of somebody who kills for a living, and how he qualifies his notion of what he’s doing from what other people might ‘misperceive’ it as,” says Fincher of the film, which was adapted from the French graphic novel by Alexis Nolent, who publishes his work under the moniker Matz. “I liked the idea of James Bond by way of Home Depot. We love revenge movies, but the reality of revenge is there’s a lot about it that should make audiences uncomfortable. We want to involve viewers in all of it.”