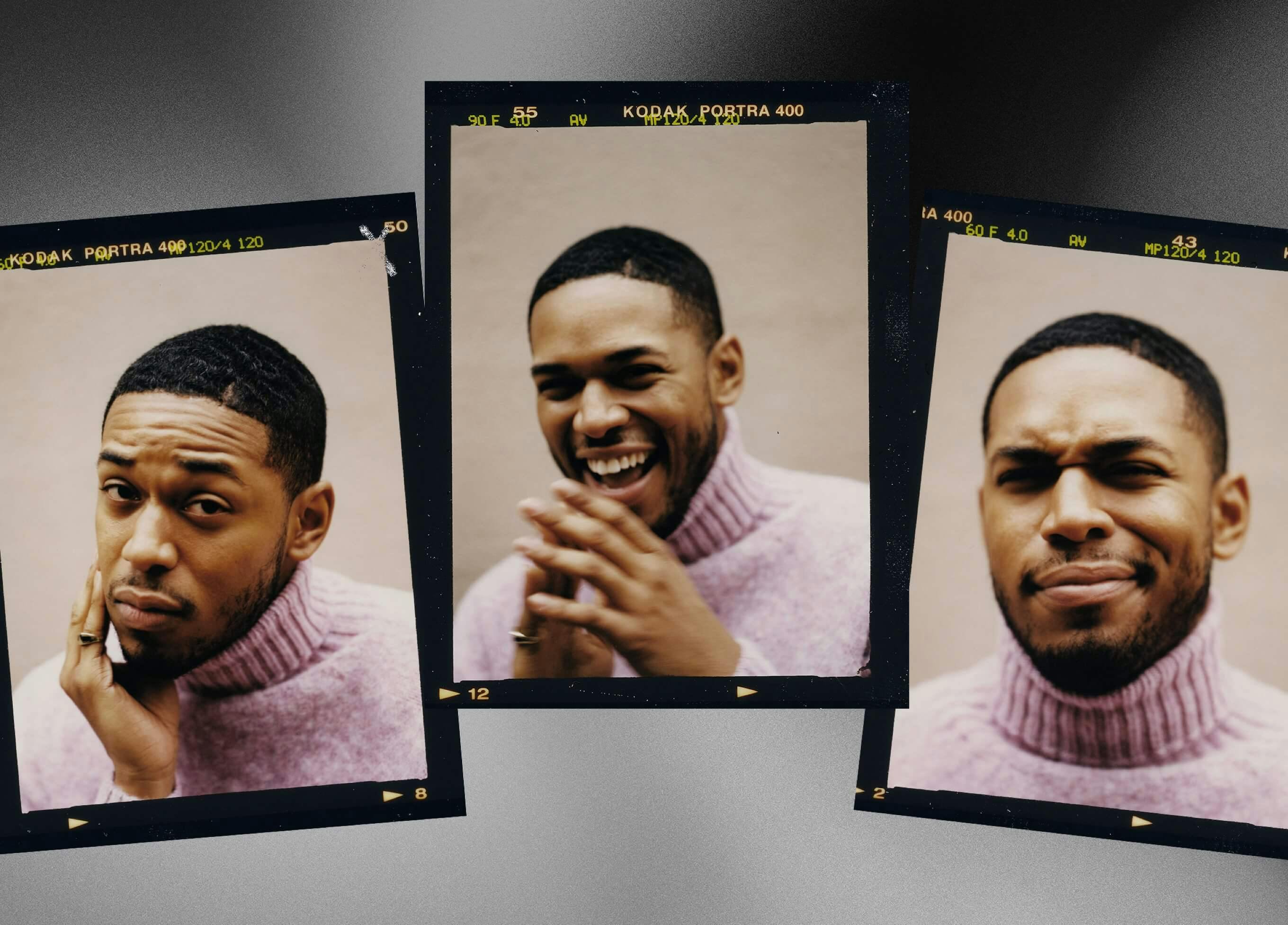

The actor discusses his first lead role in a feature film, Monster, and how he continues to learn.

Actor Kelvin Harrison Jr. can still recall the moment that he connected with the character of Steven Harmon, the New York City high school student he plays in first-time filmmaker Anthony Mandler’s adaptation of Walter Dean Meyers award-winning novel Monster. It was at the screen test where he was reading the opening monologue in which Steve ponders for the first time how he, as a young Black man, is viewed by those around him.

“It just hit me as I was sitting there,” Harrison says. “I suddenly was looking at myself, talking about something I had never spoken of before: the microaggressions, racism in high school, my upbringing in the South . . . It all started to play a role in how I interpreted that monologue. I understood that I had something to say, and something to learn. That made me excited because I don’t choose a movie unless I can learn something. Otherwise, what is anyone else going to take from the movie?”

Kelvin Harrison Jr. as Steven Harmon in Monster

It was only eight years ago when Harison started his career as an extra in the 2013 sci-fi phenomenon Ender’s Game. Since then he has collaborated with a range of actors and filmmakers across the industry. He was singled out for his brilliant performances in films such as Waves, as a highschool wrestling champion under pressure about his future, Luce, as the adopted son, a role for which he was nominated for an Independent Spirit Award,and most recently in Aaron Sorkin’s The Trial of the Chicago 7, as Black Panther leader Fred Hampton. Harrison’s initial focus as a child was music, excelling at piano, and trumpet, as well as vocals. You can hear him sing in the TV series Godfather of Harlem and the rom-com The High Note. Most recently, the 26-year-old has embarked on roles in Joe Wright’s upcoming Cyrano and Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis Presley biopic, in which Harrison plays blues legend B.B. King: “That was a man who chose joy every chance he got.”

Kelvin Harrison Jr. as Fred Hampton in The Trial of the Chicago 7

Monster, which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2018, marked Harrison’s first lead role in a feature film. His character Steve is an honors student at New York City’s Stuyvesant High School who dreams of becoming a filmmaker. When a convenience store in his Harlem neighborhood is robbed and the owner murdered, Steve is arrested, and thrust into a discriminatory legal maze.

Harrison spoke to Queue’s Krista Smith about the timely and powerful film: “I've never doubted the fact that I had something to say, I just didn't always know what project I needed to say it with.”

Krista Smith: Monster tells a complex story about race and our assumptions around race. What most intrigued you about this film?

Kelvin Harrison Jr.: My parents tried to protect me growing up. So, when I saw the script, I was just like, Oh, he’s a kid who wants to be an artist. I wanted to be an artist. I get that. And then I was like, Okay, this is a kid who is now on trial. I don’t really get that. I hear this happens. I’ve seen this happen to other Black boys. I got to go to a private school growing up; Steve got to go to Stuyvesant. I had a very diverse group of friends. I wasn’t thinking about how my race played a role in my success in life and my freedom. [Initially] I didn’t want to do [the film] because I didn’t get it, to be honest. Other people saw that I should do it because of the fact that I didn’t get it. I think Steve makes the same shift. So a lot of making it make sense was a journey I had to go on that would help this character and his development throughout the story.

As an actor, how did you approach Steve? How did he become real to you?

KH: It started with trying to understand Harlem and the community there. I grew up in New Orleans. New Orleans takes their disadvantages and turns them into something — the whole basis of gumbo is all scraps being put into a pot. Harlem does a similar thing as well, taking new music, culture, fashion, style, and trying to find fun and charisma and light in them. So, I was trying to learn how to appreciate that and apply it to this kid. But a lot of it was just tracking, what was his home life like? What were his parents like? What’s he looking for? He’s curious, just like I was at 17. How sheltered has he been? At what point is he losing his innocence? Who is he looking to for power? How do I have power in my life? Where do I have agency? That’s what young people in general, but especially young Black kids, are looking for. I based a lot of the prison stuff on my cousin, who went to prison at a very young age. My family is very Christian. I remember my aunt would tell me these stories about when she would go to visit him, and she would try to read Bibles scriptures to him and she would try to encourage him. So, I pulled from a lot of different things to make it work.

It taught me to be an observer. It taught me to listen better.

The scene between you and Jennifer Hudson, who plays Steve’s mom, when she visits him in prison is just heartbreaking. You really captured so much about their mother-son relationship, disappointment, and lack of control.

KH: As young people, we’re grateful for our parents, but we often feel like we’ve let them down and we’re embarrassed and ashamed of it. Even the scene when Jeffrey Wright, Mr. Harmon, comes into the movie, it’s similar — just this idea that the things they’ve ingrained in their child to protect him doesn’t and can’t. And we both understand that in that moment. It’s very scary knowing that. How do we move forward from there? You don’t know. You can literally gain all the privilege and power in the world that you can as a Black person and still not thrive. And they have to sit with that.

Kelvin Harrison Jr. as Steven Harmon in Monster

You mentioned Jeffrey Wright. What did you take away from sparring with him in these scenes?

KH: It was cool to watch how he needs to give himself the space to do what he does. He’s very specific about who’s passing him, any background noise happening, and all the little details of the moment. All those things feed into him being able to find peace and calm in a moment, and then giving his heart and giving a piece of himself, his spirit, and his soul through the character and the dialogue. He breathes through it and takes his time. There’s a confidence that makes all the greats great. It’s a confidence in their humanity and their understanding of their instrument that they can give forward when they feel supported. It was just cool to watch.

Did you take any of that into your other performances after working with him?

KH: Oh, for sure. After that, I was just trying to get as specific as possible, and I was trying to create space as much as possible. I ended up doing Luce and Waves and all that stuff. Really watching him and watching Jennifer Ehle, these powerhouse actors, find ways to enter a scene, to keep the momentum going, keep the movement active — because it is an art, it’s a craft as much as it is an entertainment to tell a story. Seeing how they did that changed how I view my position as an actor, especially if I’m supposed to lead a movie.

Kelvin Harrison Jr. as Tyler in Waves

Photo by A24 / Everett Collection

Anthony Mandler, this is his first feature. He cut his teeth in music videos, very famously, with Rihanna and Beyoncé. Talk to me a little bit about that collaboration, working with him.

KH: This was the first time I had a director send me a list of references — he had all these documentaries and a lot of Instagram accounts. Trying to take in the whole filmmaker aspect of [Steve], he gave me a phone, and my assignment was to go and film Harlem. I would have to turn in these little videos to him so he could see what I was shooting. Then he would talk to me about what it is that I was shooting and why I was shooting it. What is the story that I want to tell? I also kept a journal as well. This was my first time leading a movie, and I didn’t really know what I was doing. Anthony was good about allowing me to do it the way I wanted to do it and that made the most sense for me. So, I would journal, and before we started the movie, I would take the journal pieces as the scenes were scattered about, and then investigate those moments. A lot of the voiceovers are rewritten from my journal entries of when Steve was in prison. Even when we were shooting there, he would leave me the whole day so I could really take it in. We would roll the camera to see what we’d discover. It felt like improvisational jazz a lot of the time. It just had this cadence to it. It was very open.

You grew up in a very strict household centered around music. Your father was a musician, and your mother was a musician and vocalist. There was a real commitment within the family for you to excel in music. What positives came out of that experience?

KH: It taught me work ethic. It taught me that I’m capable of doing a lot more than I would allow myself to believe. It truly is about a mindset. I think the reason why I’ve been able to do so many movies in this short time span is mostly because I don’t stop. I’ve taped with some actors and they’ll do a couple of takes and that’s that — and that’s fine, no judgment. I think about it like I was practicing when I’m auditioning. It is an opportunity to practice my craft. My dad pushed me to understand jazz and classical music, which helped me be able to have a conversation around storytelling, and to open my eyes to different ideas. I apply all of that when I’m working. If I don’t have anything to say, I don’t need to say anything. It taught me to be an observer. It taught me to listen better. Ultimately, it taught me to be very disciplined. Sometimes I don’t really have a life, but I find great joy in it, you know?

Kelvin Harrison Jr. as Steven Harmon in Monster

How do your parents feel now that you are clearly ensconced in this profession as an actor — you’ve already been nominated for an Independent Spirit Award. Have they accepted it and embraced it?

KH: My dad has all the movies, and he watches them like once a week. It’s very interesting because at first it was like, you should finish school and you should continue playing music. But now that I’ve been able to make my own way, they get really excited, especially about the roles that I’ve done. I’m playing musicians a lot now, too.

Like B.B. King. How was that?

KH: It was so much fun. What I love about these icons — when I get to play them — is that they’ve lived a whole life and the things that they’ve had to discover to get there, are free wisdom. You get to sit there and investigate it and then apply it as much as possible. He loved his job. Even through all the oppression, you think about the light he was able to put into it and the passion. It’s changed my perspective on my career and the roles I choose.