Crip Camp co-directors Jim LeBrecht and Nicole Newnham explain how a New York summer camp launched a movement and their movie.

When Jim LeBrecht was 15 years old, he had a transformative experience at summer camp. The year was 1971, and for people who used a wheelchair, like him, finding adequate public accommodation was rare and achieving true visibility was difficult. Although he was affable and outgoing, Jim often felt like an outsider at his high school. At Camp Jened, located a few hours outside of New York City, he found camaraderie and empowerment.

Jened played a similar role for an entire generation of its campers, all of whom were disabled. Many of them would go on to become a united political force working to end disability discrimination. Their stories are told for the first time in the acclaimed documentary Crip Camp, which LeBrecht co-directed with Nicole Newnham. (The pair previously worked together on projects including the 2006 documentary The Rape of Europa, which Newnham co-directed and LeBrecht sound-mixed.)

Crip Camp co-directors Nicole Newnham and Jim LeBrecht

Photo by Sacha Maric

Executive-produced by President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama through their production company, Higher Ground, Crip Camp features candid footage from Jened’s heyday, then jumps ahead to track its subjects’ evolution into young activists. Since the documentary’s world premiere at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2020, where it took home the Audience Award for U.S. Documentary, it has become a cultural flash point in a way neither filmmaker anticipated.

“I remember reading a response from somebody who said, ‘I feel knowable now,’” LeBrecht relates. “It hit me in the gut that somebody would feel that way, that our film would be something that made their life feel better.”

LeBrecht and Newnham recently spoke to Crip Camp’s international impact campaign advisor, renowned writer and disability advocate Sinéad Burke, about the documentary and how one summer camp changed the course of civil rights history.

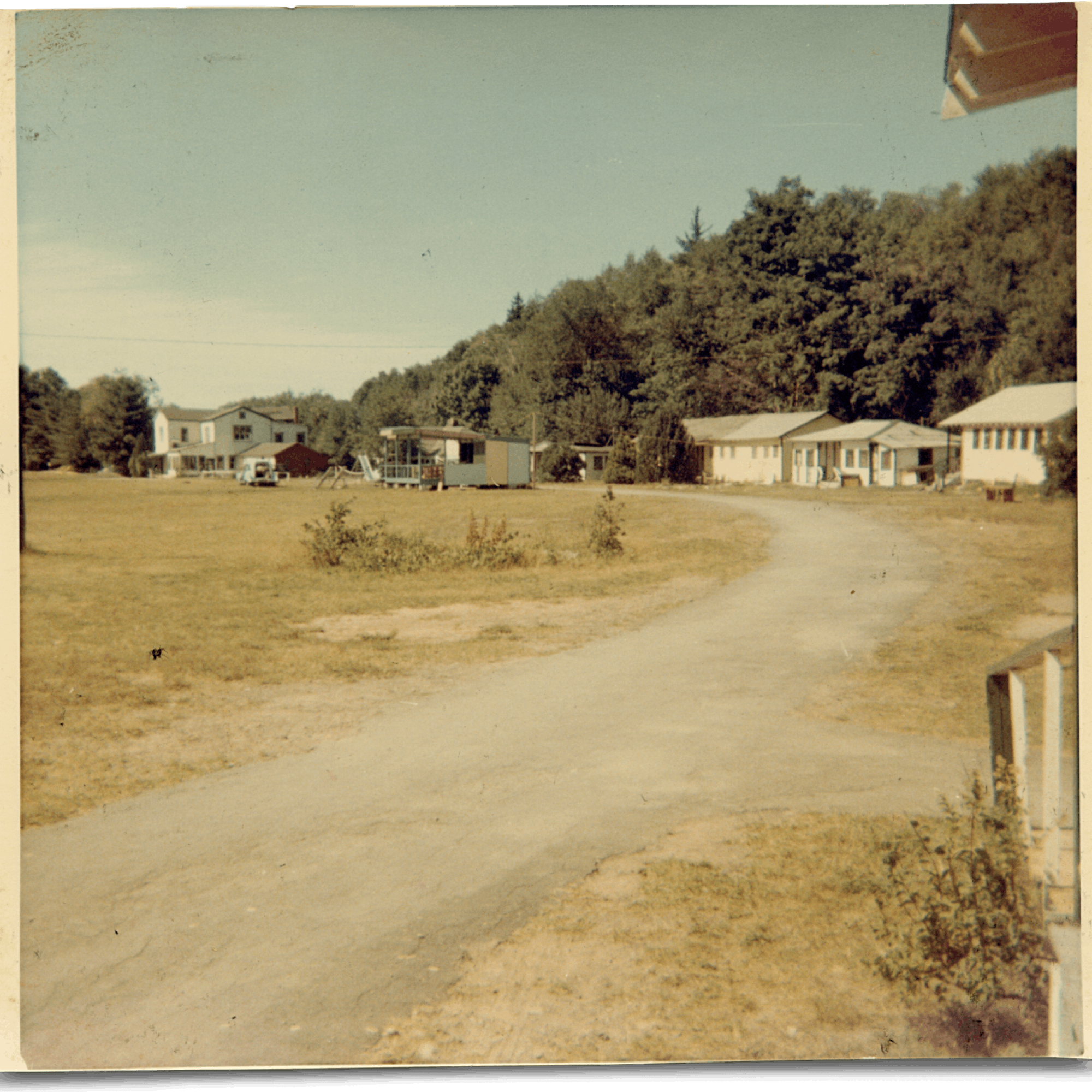

The road through Camp Jened

Photo by Joyce Levy

Sinéad Burke: The two of you have been friends for such a long time and have worked on many projects together. But as co-directors on Crip Camp, your relationship was different. Did you have to make space for one another in a way that was different from how you had worked previously?

Jim LeBrecht: Although we’ve known each other for so long, with Crip Camp we were in each other’s lives daily. I got to know Nicole and her husband, Tom, and her two wonderful boys, Finn and Blaine. For me, that’s important. You can approach things like this as a job, but not when you are trying to make a film with a lot of heart. We had to find and forge this collaboration as business associates, as partners, and as friends. Underlying all of this was a real trust, and that is the solid bedrock of what happened on our film.

Nicole Newnham: I would agree with that. I like to co-direct. I’ve always co-directed. For me, it’s making space for someone else to have full agency in a project. Working until you get to consensus artistically and creatively is something that I enjoy. I took the lead on the story architecture and how the edit fit together. Jim took the lead on what this film had to say, and how it was going to be said in an authentic way that was going to speak to a disabled audience and represent the disability community.

It was tricky because it was Jim’s life, and it was a lot of emotional, personal work that he had to do. I was consistently in awe of how he was able to come into the room and look at a scene as a scene, when it was also about some very emotional part of his own life or it was about a person that he loved deeply from his past but whom we were talking about as a character within the complicated architecture of a story.

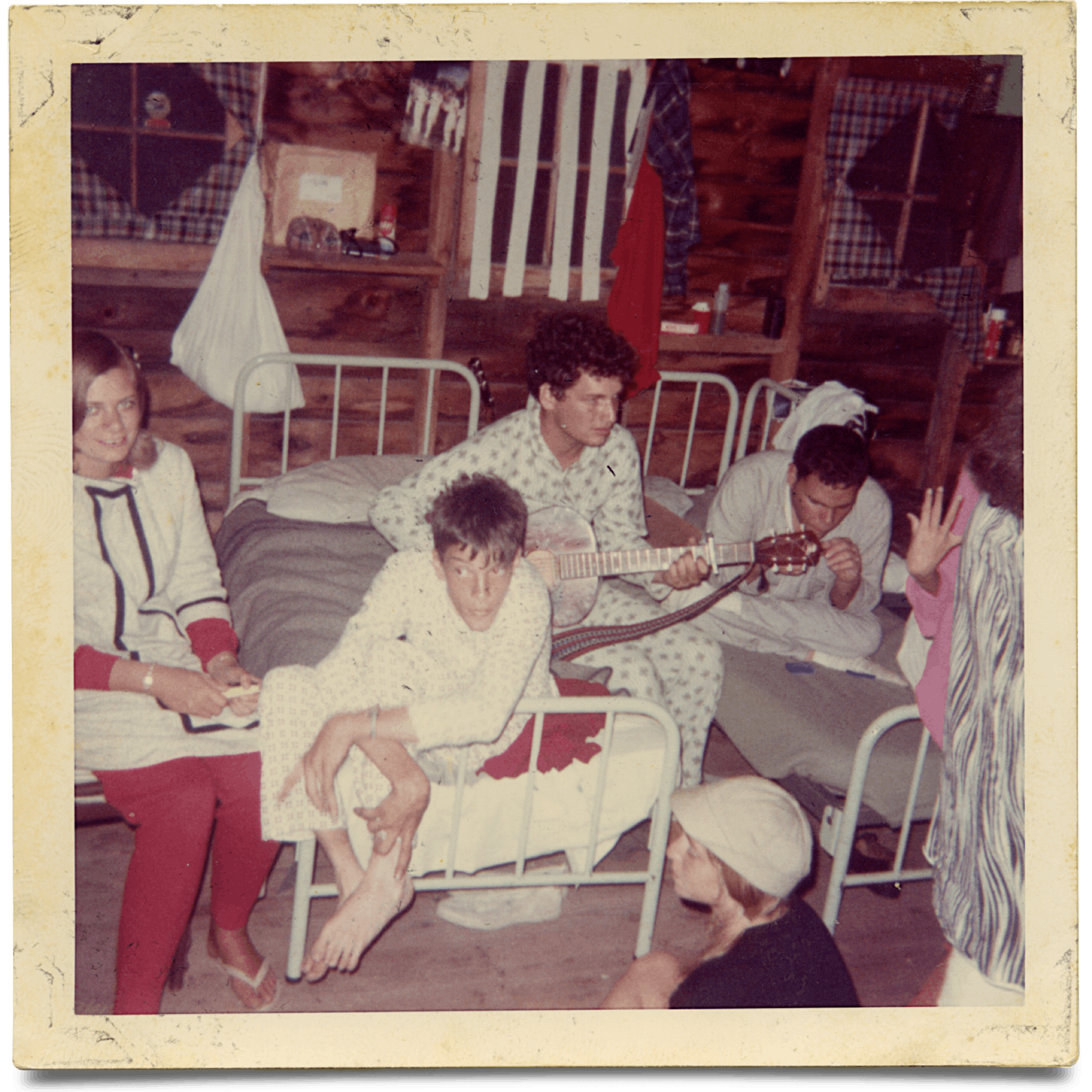

A night at Camp Jened

Photo by Joyce Levy

Crip Camp charts the evolution of the disability justice movement in the U.S., but it is deeply entrenched in Jim’s own story. Jim, looking back at that summer, what made you want to be an observer and a participant in such a historic moment?

JL: All of that black-and-white footage from ’71 was a result of this wonderful group called the People’s Video Theater coming to Camp Jened. They showed up and wanted to use this new portable video technology as a tool for marginalized communities. They said, “Would you like to make a film about your camp?”

They came to Camp Jened’s drama and camera club with their equipment. Shortly after that, they asked me if I’d like to do a tour of the camp. They strapped this really heavy tape deck to the handlebars of my pushchair and then handed me this video camera, which wasn’t terribly light either. Somebody pushed me around camp — I think it was probably Howard Gutstadt from the People’s Video Theater and one of the counselors. And as you can hear in our film, they said, “Just tell us wherever you want to go. We’ll go there.”

A summer day at Camp Jened, 1971

Photo by Denise Sherer Jacobson

Did you feel empowered by that process, or observed?

JL: Oh, totally empowered. Here’s the thing — I realized this when I was watching the footage with Nicole. One of the first things I remember saying was that these folks could have come in and gone to the camp director and said, “How are you taking care of these poor handicapped children?” They didn’t do that. They gave us agency. They treated us like any other group of teenagers and young adults. And that just didn’t really happen in our lives.

Where do you think that approach came from?

NN: They were revolutionaries. They were running these pop-up video theaters and they would go to all these different movements. They were with the Black Panthers. They were with the women’s movement. They were with the gay rights movement at the time. They would literally be in the street filming people and then showing them themselves back on these big video monitors as an empowerment tool.

There were two main guys who were at Camp Jened whom we got to know because we found them and interviewed them for Crip Camp. One of them was Ben Levine, who was doing some of the filming and interviewing that summer. He had actually done a lot of work in Pennsylvania with young people with disabilities, in a program in which he would take these large-format black-and-white photographs of them as a process of workshopping how they felt about themselves. I think he had a very deep and profound understanding of how that social justice approach of using film as an empowerment tool could be valuable in this community. He brought a lot of real heart and sensitivity to the work.

Demonstrators march for the passage of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, a precursor to the Americans with Disabilities Act

Photo by Hollynn D’lil

Jim, when camp ended that year and you returned to your community, did you have any sense that you had changed? Or did life just continue?

JL: I had the perspective of a 15-year-old boy. I thought it was cool that I got to do this. I have to say that it was an amazing experience, but there were so many other things at that camp that added to my enrichment, that added to my sense of self and learning how to be prideful. The overall experience there was what enriched me, but when I went back home, I played baseball in my wheelchair, I was waiting to see my friends on the block. It’s only through years of looking back, and especially working on our film, that I can see how critical those summers I spent at that camp were. They absolutely made my life what it is today.

Activist Judy Heumann demonstrates for disability rights in Crip Camp

Photo by Hollynn D’lil

I love the idea that what is now such a revolutionary moment was kind of ordinary when you were 15. You didn’t know in that moment that the footage you had just recorded would go on to be a Netflix Original film produced by Barack and Michelle Obama. It only makes it, I suppose, even more special. But as you began to work on the film together, did you imagine what its success would look like?

NN: I don’t think we could have imagined this level of profile and platform. The Obamas coming on board, we did not imagine that. We did have our sights set very high, though. We saw that there was this amazing movement that was exciting and fun and cinematic and hadn’t gotten its due in the film world. It had been explored as a serious documentary subject, but not as a full, entertaining, cinematic experience — not as this universal Breakfast Club or Wet Hot American Summer coming-of-age story.

We had high hopes, but we struggled a little bit to get other people to see what we saw. When we were able to cut together some of the footage, even into a small trailer, people started to respond in a really powerful way that let us know that we were on the right track. It also led us to realize that we wanted this to be a film that could be on a global platform and could play a role in shifting perception for viewers, and also within the media itself, around what a disability story can be.

Neil Jacobson, Denise Jacobson, Judy Heumann, Nicole Newnham, and Jim LeBrecht celebrating the Audience Award win for Crip Camp at Sundance Film Festival

Photo by Sacha Maric

What impact would you like Crip Camp to continue to have?

JL: There’s an amazing thing that seems to be happening this year that I know that we’re a part of, which is shedding a light on the fact that stories around disability don’t have to fall into the old tropes. They don’t have to be tragic or inspiration porn. Crip Camp shows the full rainbow of experiences that one has living with a disability. That’s personally what I’m hopeful for in the future. When you have filmmakers with disabilities telling the stories and doing it well, you realize that obviously that’s the way to do it. This is what we know from every other marginalized community, right? We need people from the community as directors, as producers, as casting agents. I’m not saying that allies aren’t important; they truly are. But what are we all after in this world? Authenticity. We want something that feels real and dramatic and new and exciting and sexy and funny and compelling.