Documentarians Coodie & Chike on the divine journey of jeen-yuhs.

Ascending the ranks from local mixtape rapper to global superstar is a remarkably long trek. It’s a path that, some would say, is divinely ordered. Kanye West stayed the course and so did directors Coodie and Chike. jeen-yuhs: A Kanye West Trilogy, the duo’s latest three-part documentary, has been in the making for more than 20 years. “If God wants this to be stopped, it would be stopped, and we [would] just wait another 20 years,” says Coodie. “You can’t stop what’s ordained by God, no matter what. Because he’s the creator. You know what I mean?”

Since 2003, Clarence “Coodie” Simmons and Chike Ozah have collaborated on music videos, short films, and documentaries and eventually adopted the production company banner creative control. As a team, Coodie and Chike are passionately spiritual; they point to each career turn and every stroke of luck as evidence of divine intervention and the will of a higher force. The three-parts of jeen-yuhs outline a spiritual perspective Coodie feels their journey followed with episodes titled “Vision,” “Purpose,” and “Awakening.”

jeen-yuhs closely documents Kanye’s transition from an in-house producer for Jay-Z’s Roc-A-Fella Records — creating critical and commercial smashes for the label’s roster — to a headlining solo artist representing a Midwestern, collegiate middle-class sensibility that was entirely new to hip-hop at the time. The documentary’s first half captures Kanye’s 1998 – 2004 tenure as pop’s most bewildering hip-hop head, before his debut album, when he was bringing a pop-savvy, high-low sensibility to tracks for Talib Kweli, Jay-Z, Dilated Peoples, and Alicia Keys. We witness Kanye press himself into popular culture, hijacking rappers, actors, studio sessions, even MTV’s edit bay, to self-actualize his vision.

At the time, Chike, who was a graphics editor at the network, provided a crucial piece to Kanye’s early team. “My whole goal in life at the time was to do music videos,” Chike recalls. “When I was in college at Savannah College of Art and Design, I was like, I hope to get a job at MTV, because that’s where I’d meet an artist in the hallway and be able to do a video. That’s where I met Kanye. He knew what my passion and my skills were, but it was at MTV where I was really able to hone those skills of directing, of doing music videos.”

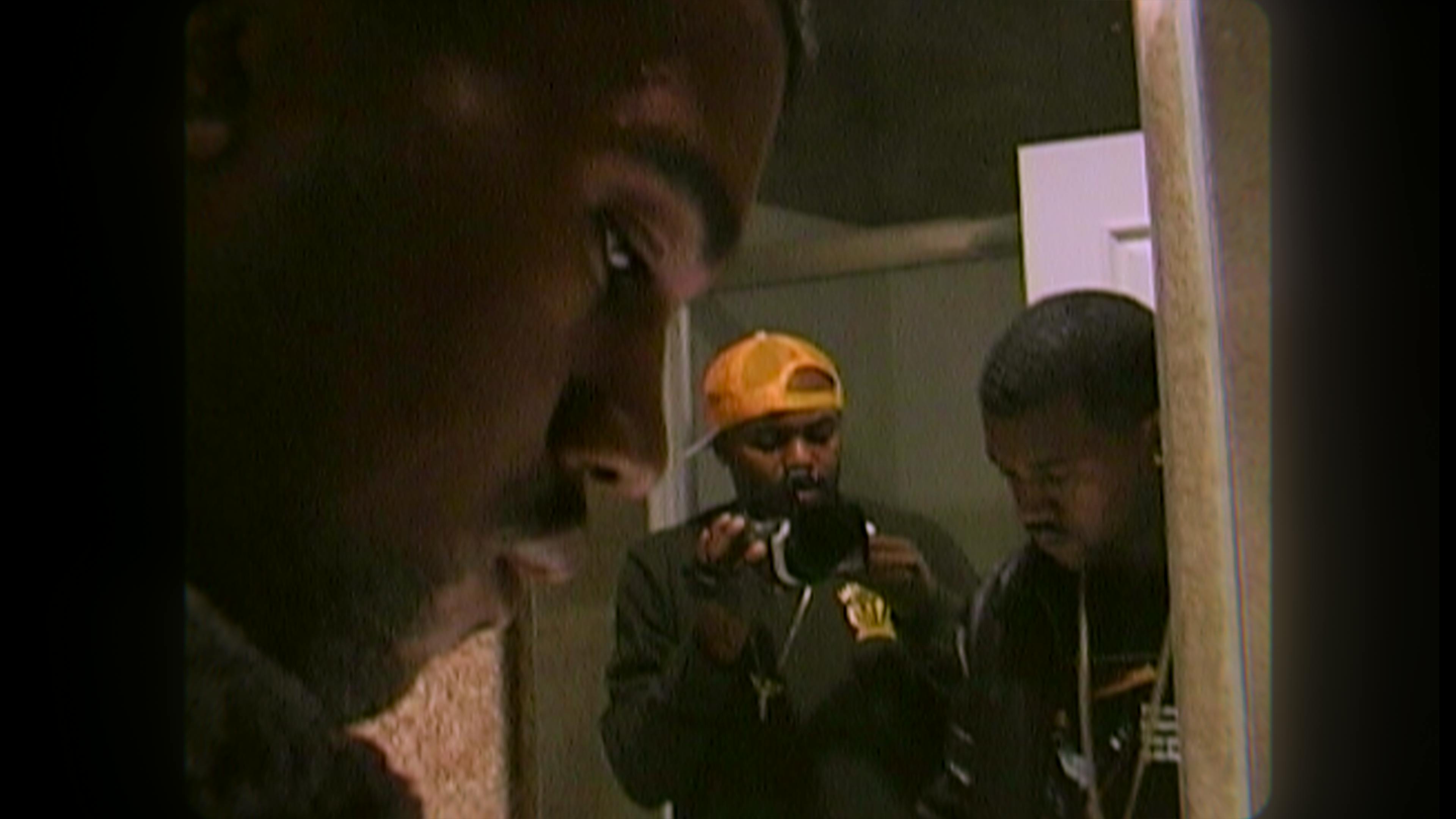

Coodie Simmons and Chike Ozah

As Chicagoans making the rounds on the city’s music circuit, Coodie and Kanye had already forged a close bond. Coodie tailed Kanye through studio sessions in New York, documenting his day-to-day life in hopes of producing a full-length documentary film. Once Chike joined up, the trio would be nerding out over typefaces and film grains late at night at MTV, stitching together what would become Kanye’s first music video, “Through the Wire.”

jeen-yuhs offers up deeply candid snatches of daily life during a period of recent history that is hard to recount. Much of the footage from 2000 – 2004 falls between the bulky VHS home videos of the 80s and 90s and the soon-to-be ubiquitous digital cameras and camera phones of the late 00s. Still, watching jeen-yuhs rewards viewers with rarely seen footage: clips of Roc-A-Fella’s modest offices, an only slightly sanitized Times Square where you could still buy nudie mags at a newsstand, the billowing, layered fabrics of early aughts fashion. The term “time capsule” hardly does it justice.

In order to collage the footage they captured, the directors sifted through 330 mini DV tapes, which had been stored away for more than 20 years. Each tape was an hour long, and Coodie says he’s sure there’s more footage of Kanye on stray tapes he hasn’t yet reviewed. “There are about four more 100-hour mini DVs that got Pitbull, John Legend, and J. Ivy that we didn’t upload and digitize,” Coodie says. In a bittersweet blessing, the COVID pandemic finally allowed the duo the time to scour their comprehensive video archive. “We say, ‘God always moves in mysterious ways,’” reflects Coodie. “The world shut down, [and we could] look at all of this footage, and go through it.”

Among the most precious imagery that jeen-yuhs affords us are the intimate glimpses of Donda West, Kanye’s late mother. Much has been said of their incredibly close relationship — Donda famously penned a memoir titled Raising Kanye: Life Lessons from the Mother of a Hip-Hop Superstar that details their multifaceted dynamic — but never before has this level of visual access been granted. The two share candid, extended conversations at her kitchen table and stoop hangs outside Kanye’s childhood home. His mother even makes cameo appearances at the recording studio with P. Diddy and on national television with Oprah — Donda’s presence in Kanye’s early career is abundant.

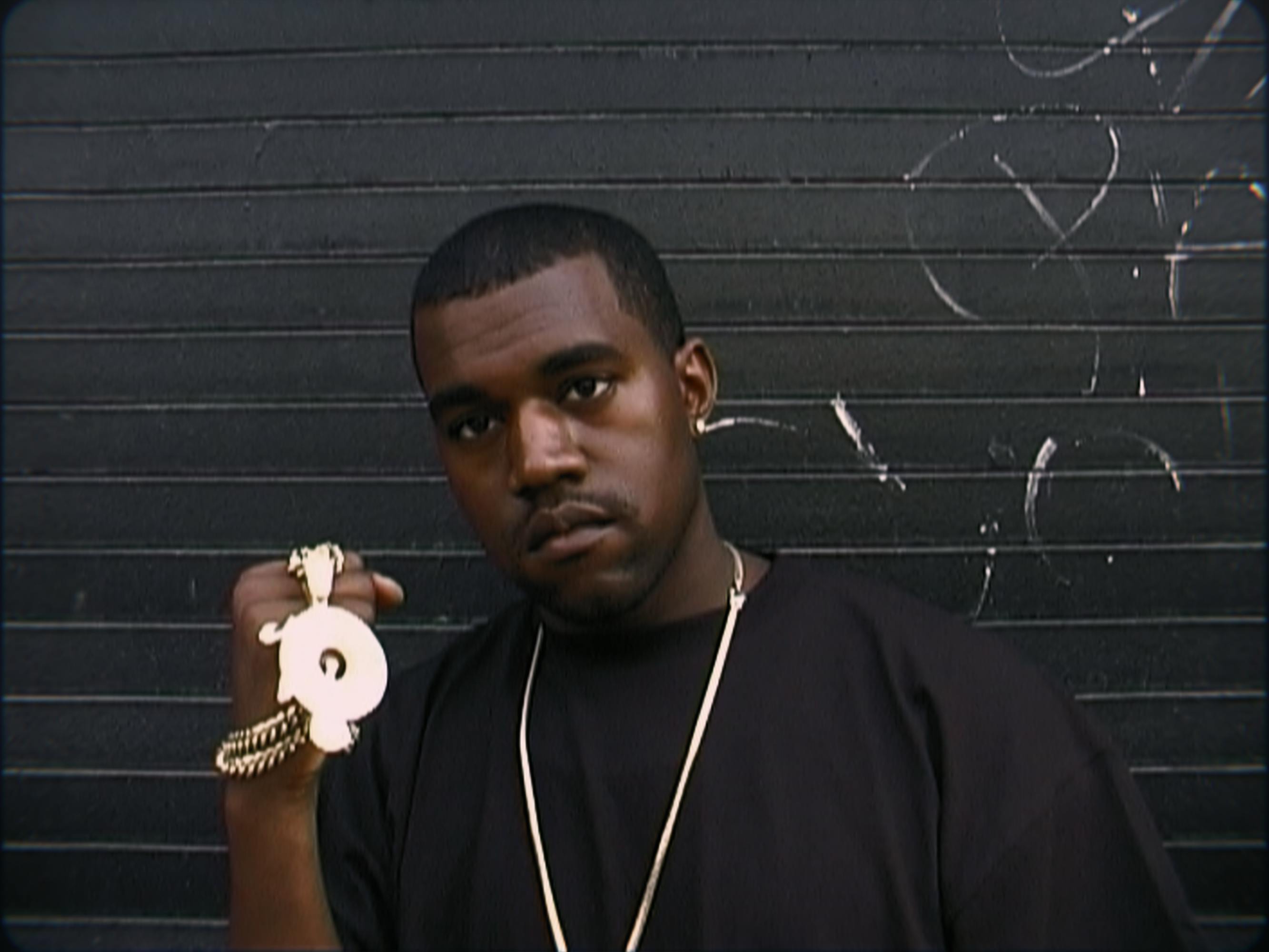

Ye

The filmmakers capture a parental devotion that goes beyond the norm, even by a mother’s standards. Donda peppers sentences with his name, as if she simply loves to say it; she recites old rap lyrics of his that even he can’t remember. As viewers, we anticipate the sorrow of her untimely passing, and many fans have theorized the effect this had on Kanye long-term (he has hardly ever openly discussed it). But to see, through Coodie’s footage, his weightlessness in her presence, the clarity and purity her companionship provided his music, is to see a jarring before-and-after portrait. One gets the feeling that those who were early Kanye fans were actually Donda fans and didn’t even know it. “Mama West always kept me around,” says Coodie.

It is this then-and-now divide that defines the jeen-yuhs viewing experience. A more balanced Kanye documentary might have evenly paced its gaze on each album, phase, and chapter of his career. But by the third act, we are rushed from the cusp of Late Registration in 2005 and Donda’s passing in 2007 to seven years into the future; Kanye is married, has had his first child, North, and is fully in his Yeezy fashion crusade. We hardly get a glimpse of the years in between — none of the shutter shades of “Flashing Lights,” nor the Auto-Tune of 808s & Heartbreak. Ultimately, the ebb and flow of Coodie’s relationship with Kanye is the documentary’s true subject, and these gaps in timeline are equally part of the story. When he is summoned, Coodie provides a bro’s-eye-view to Kanye’s most intimate creative proceedings. But when he is shooed away, clips from news telecasts, award shows, and interviews fill in the blanks. The filmmaker sees these years as the passive viewer might have, in a distant third-person.

When discussing their time apart, Coodie is sensitive but reflective on how and why he thinks their relationship waned, and how they continue to find their way back to each other. “Kanye first didn’t want to do [the documentary project], early on,” Coodie remembers. “And he said recently that if footage would’ve come out early, he would’ve felt embarrassed.”

In many ways, the series’ existence itself has provided common ground for the two early collaborators to reconnect. Coodie and Chike faced resistance throughout its production — “We were hearing stuff like, This’ll never see the light of day,” says Coodie — and even Kanye’s blessing was at times unreliable. “I showed them the sizzle [reel] back before we even started, so we were in communication then,” Coodie says. “I told him what this movie was about and that we already had a cut. It was easy for me to tell him that this movie was for the dreamers — and not about us. And then we would talk steadily, but there was so much that would happen in the communication. [Kanye] was always supportive. But then when we’d get off the phone, we’d hear from his team, like, ‘Yo, we need this, we need that,’ and I’m like, ‘What’s going on, man?’ But then I’d just say [to myself], Trust God.”

Ye

The moments of creative turbulence in getting the documentary series released mirror the glimpses of Kanye we see in the last act. During several of the documentary’s last scenes, we are never too sure which Kanye we’re going to get — lucid, self-assured, reserved, or unhinged. The last images of Kanye that jeen-yuhs captures are familiar to those who have seen the news headlines that bear his name. The filmmakers suggest that, through it all, the presence of old friends serves as a grounding force for Kanye today. “Every time I’m with Kanye feels true to him,” Coodie says. “He knows that I know him 100%, from all the time that we shared together.”

“Coodie’s the type of friend that’ll definitely hold you accountable,” Chike adds. “He has no problems telling you, or questioning you, or asking out of concern, out of love. It’s all out of love. If he knows who you really are and he sees a change, he’s going to bring it up. And we need people like that in our lives. Those are anchors; everybody needs anchors.”

Still, in what might be the documentary’s thorniest bits, the filmmakers ultimately exercise their discretion on what to film and what not to. “The time when I had to turn the camera off — I talked to him the other day, and he joked about it,” Coodie says, “[Kanye] was talking about something serious, and he was like, ‘Man, but when I talk this way, people want to turn the camera off!’” Coodie laughs. “Some things I had to pay attention to. I turn the camera off cause I need to pay close attention to what’s going on, and everything doesn’t have to be on camera.”

It is a particular kind of balancing act to consume such up-close looks at both the “Old Kanye,” a soul-bearing people’s champ, and the “New Ye,” a sharp, angular agit-poster who many are running out of ways to root for. It is hard to imagine where the two meet, but one of the most affirming throughlines in the series is the presence of Old Chicago: Among the various crowds are faces who have remained around Kanye since the very beginning — Rhymefest, Don C, Ibn Jasper, Common, John Legend, Coodie, and Chike. “I think God moves that, you know what I mean?” Coodie says. “Even after he broke down on the Saint Pablo tour, for God to bring us back together the way he did . . . It’s been so many times when God was just showing us, ‘Yo, I got dude. I got Kanye.’ Every time anything happens, he always brings a team around. That’s our brother, so we are always going to be there for him, no matter what.”

Even after completing jeen-yuhs, what remains clear is that if there is one subject that even a three-part documentary and seven and a half hours couldn’t comprehensively capture, it’s Kanye West. “I think [former Roc-A-Fella A&R] Big Face Gary said it best [in the series],” Coodie says. “In the first episode, he said, ‘Man, y’all still working on the documentary?’ And Kanye said, ‘No, we just started.’ And I say, ‘It’ll never be finished.’ It’s still going. The story’s still going.”