Graham Coxon and Mark Mothersbaugh score a different kind of hit.

Graham Coxon and Mark Mothersbaugh built careers in bands that added to the cultural soundtracks of distinct times and places. For Coxon, it was 1990s England, as part of Blur; for Mothersbaugh, it was the United States of the late 70s and early 80s, as a member of Devo. Those groups have produced new work and toured from time to time over the years, but Coxon and Mothersbaugh have yet another outlet for their musical mastery: film and television scoring.

Mothersbaugh has been composing scores for decades with his production company, Mutato Muzika. The projects in his back catalogue range from Pee-wee’s Playhouse to The Royal Tenenbaums, from Thor: Ragnarok to Tiger King. Coxon is newer to the field, but has already made his mark with work on cult favorites The End of the F*ing World and I Am Not Okay With This. These scores enliven onscreen worlds just as the music of Blur and Devo invigorated places and times and generations.

Mothersbaugh’s and Coxon’s most recent Netflix projects are disparate: an animated, whimsical children’s film (The Willoughbys) and a quirky supernatural teen dramedy (I Am Not Okay With This), respectively. The composers come from different eras and different continents — and they’ve never crossed paths before — but when Queue set up a conversation between them, the two found common ground in their influences, and a deep admiration for each other’s processes.

Mark Mothersbaugh and Graham Coxon

Mothersbaugh by Magdalena Wosinska; Coxon by Guitarist Magazine

Madeleine Saaf Welsh: What is an example of a film or series the score for which you remember being absolutely blown away by?

Mark Mothersbaugh: I remember the first time a film score really struck me was when I was at Kent State. I didn’t know what I was doing in college; I was just there because I thought, I can’t think of one Vietnamese person I want to kill, so I’ve got to figure out some way around that. Nobody in my family had ever gone to college before. I just kind of blundered into it, but it turned out to be this amazing place.It was a very creative time. We used to watch movies in a classroom from a 60-millimeter projector on a small screen, and I remember going in one time and watching a movie by Fellini called Satyricon. There was almost no dialogue in it, but the amazing thing was the music was all these nontraditional instruments. It just totally knocked away the idea of using an orchestra for a film score. It was ram-horn sounds, and whirling leather buzzing devices, and strange, thick leather drums that really had a very primal feel to it. Nino Rota scored it, and I remember thinking that it was the most amazing music for film.

Satyricon was the movie that woke me up to the concept of music in films.

Mark Mothersbaugh

Graham Coxon: As a kid in the 70s, I was always fascinated by spy films. I could never make head nor tail of anything going on in a spy film, but the atmosphere and the footsteps and all of that — I just loved it. Then, later on, with things like The French Connection and Don Ellis with his quarter-tone trumpet, I think that captured a real mood for me.

I did get rather obsessed, like lots of people, with Ennio Morricone and the Sergio Leone films. The emotion in some of those Morricone scores — when it’s not just action, but the really emotional pieces, like “Goodbye, Colonel” [from For a Few Dollars More] — are incredibly moving, musically. . . . Then on the other side of it, there’s things like Suspiria, from ’77, which I can’t even watch, it’s so brutal. But the music is so scary. The extremes, I really dig that.

MM: Yeah, Satyricon was the movie that woke me up to the concept of music in films. The year I’m talking about is ’69, so I’m already totally British-invasion damaged at that time in my life. Satyricon was the movie that made me go, Wait a minute, there’s a bigger world out there.

You both talked about instrumentation being important to these scores. How do you approach selecting the right sounds or instruments to create the world of the film or series?

MM: Musically, I was in a band that was enamored with art movements in Europe between World War I and World War II, and so that included the futurists. I loved their concept of music, and I loved that sound didn’t need to be relegated to an orchestra. When I segued from being in a band and found myself in the world of TV shows and films, I liked that idea.

There was this guy from the 30s, Spike Jones, who was almost like a Dadaist. He had a band, but he used a lot of sound-making devices to create his music, and I loved that. Sound-makers and sound-making devices have always fascinated me — like for Pee-wee’s Playhouse, which was kind of the first thing that really got me into it. It was a successful show, and so it gave me the feeling like, Well, why base it on a standard piano melody and rhythm? Why not look for something that you could put in there that would infect your project with its own universe? Something where you would hear that sound, or you would hear that rhythm or that melody, and you could be in a different room in the house and go, Oh, my TV show just started. That’s what made it fun.

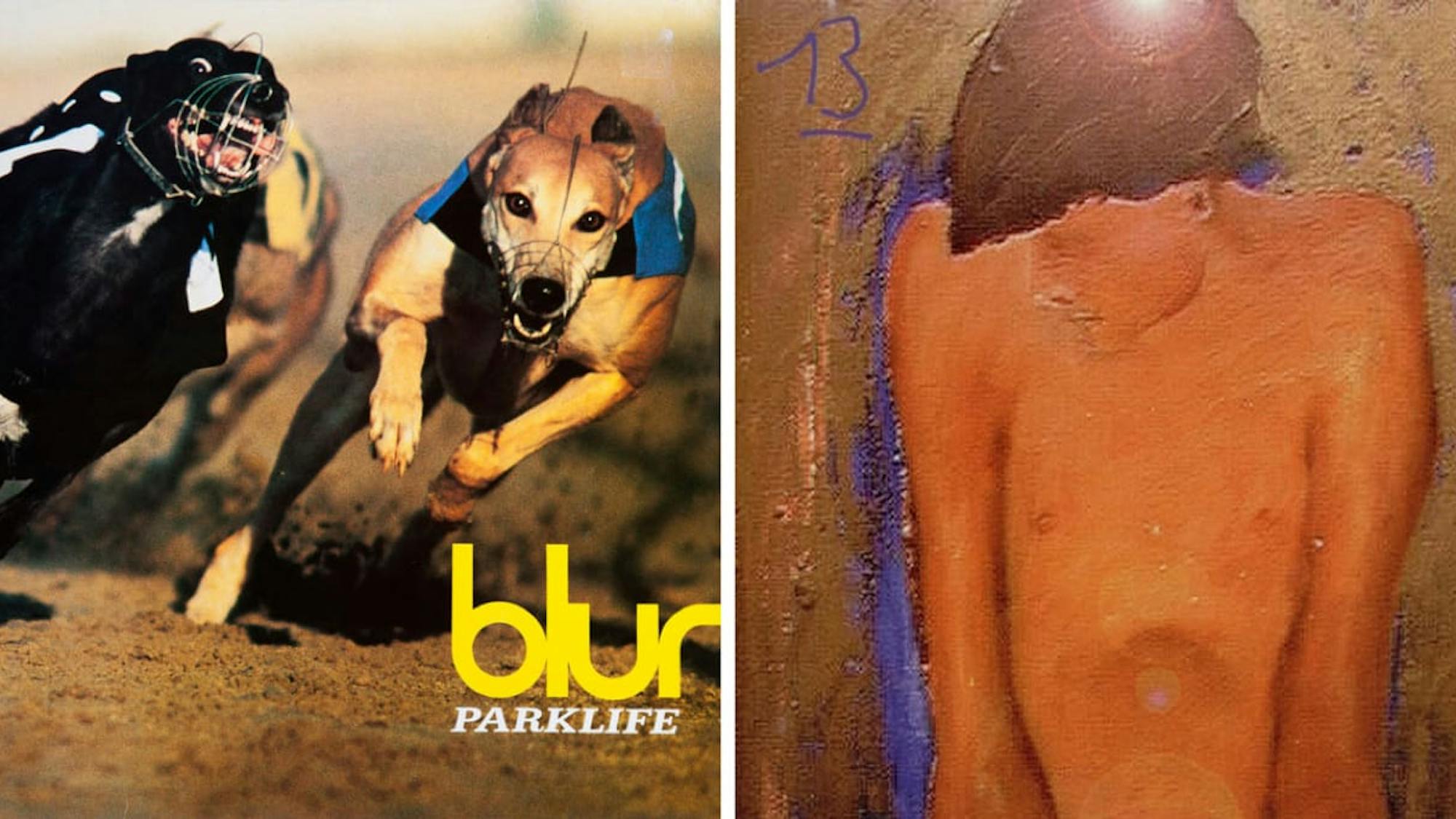

Blur albums Parklife and 13

Parklife by Eyebrowz / Alamy Stock Photo; 13 © EMI Music Japan

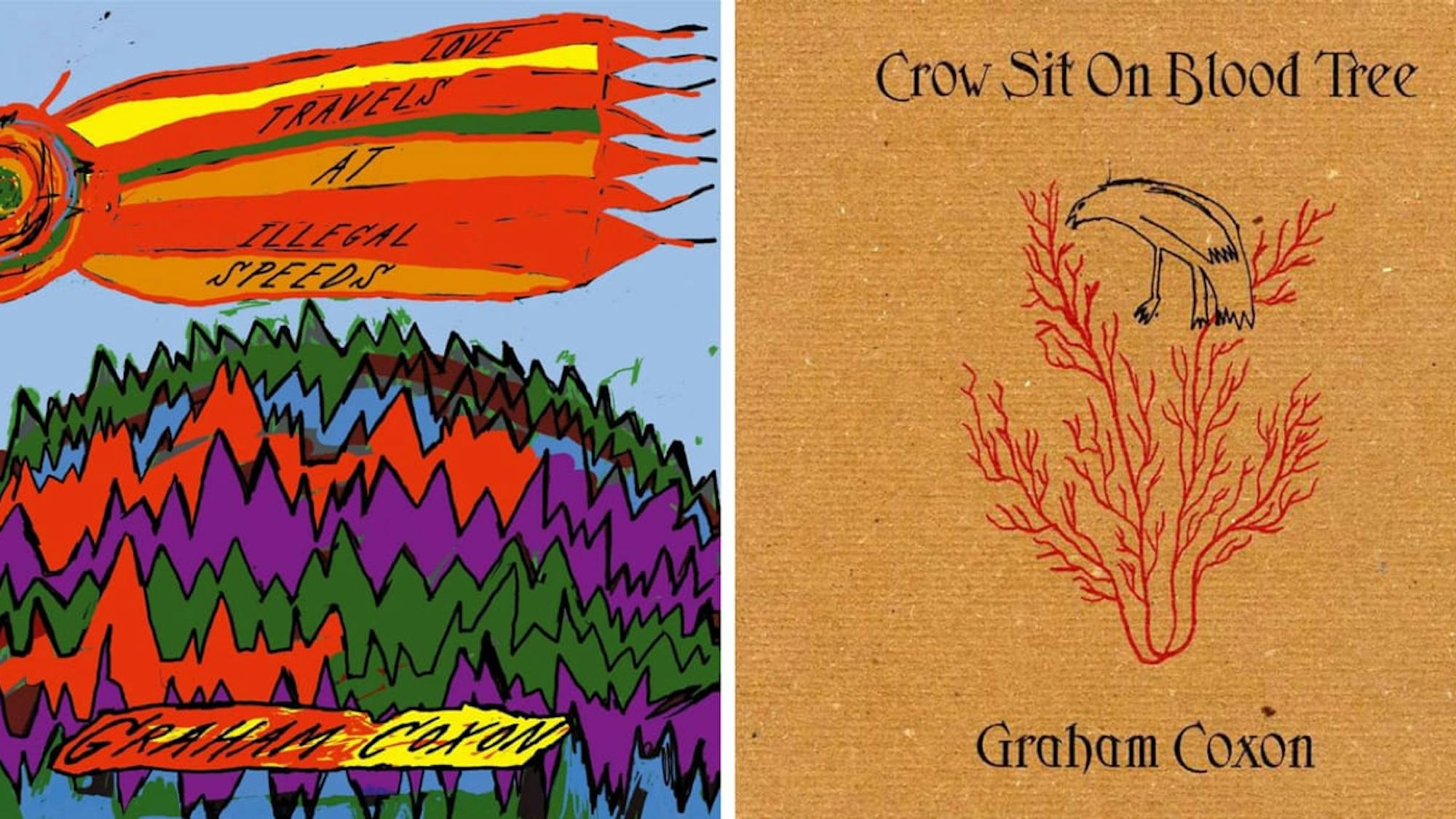

Love Travels at Llegal Speeds and Crow Sit on Blood Tree, solo albums by Graham Coxon

Love Travels at Llegal Speeds © Parlophone; Crow Sit on Blood Tree © Transcopic Records

GC: That’s really interesting you talk about Spike Jones, because Blur were huge Spike Jones fanatics. In the very early days, Blur’s bass player, Alex James, had The Best of Spike Jones and His City Slickers, and we would listen to that all the time and be in hysterics. “You Always Hurt the One You Love,” with the insane horn bit and the huge tubular bells clanging through it . . . It almost reminded me of the Carl Stalling stuff, the cartoon stuff. It was just incredibly funny and smart and chaotic. I played that recently for my little girl, and she doesn’t quite laugh as much as me.

MM: Oh, that’s too bad.

GC: Well, she sort of just stares into space and is trying to take it in, because there’s a lot happening. It’s just chaos, but I love it.

A lot of the stuff I’ve been asked to do has been sort of similar, and it’s to try and do a song a bit like “Paris, Texas,” but have it in Essex, England. Or I get asked to do something that’s kind of old-timey-sounding, like Roger Miller or Burl Ives. I got really into trying to make a recording sound old: so using the dullest acoustic guitar I could find, and rolling off the top end and bottom end, and trying to do something with my voice — trying lots of ways to make it sound like it’s been buried in the back garden for 50 years.

It’s still absolutely magic that these things come into existence over the course of a day, and there’s this new thing out there in the world.

Graham Coxon

MM: You’re super fortunate that you’re the person that they think of for that, because there’s plenty of jobs that ask, “Can you make it sound like John Williams?” They pick two or three composers, and then that’s what you get, that’s your job. You’re just trying to sound like somebody else, so you might as well be tiling a kitchen or something. You’re a craftsman, but you don’t get to be an artist. So you’re lucky: You get asked to be an artist.

GC: It is sort of nice. In the first season of The End of the F*ing World, there was this little song that was like a little country-blues song. It’s a simple little tune, a simple fingerpick thing, and people seemed to really connect with it. It was written and recorded very, very quickly, and not recorded particularly slickly, but I liked the idea that you could write something and record it in the space of an hour, and you send it off, and then suddenly lots of people are hearing that thing that you hardly remember creating because you did it so fast.

MM:That’s kind of what’s fun about scoring. When you’re doing an album, it’s very precious, and you take it home and you think about it, and then you go back and work on it some more, and you keep going back. I love it in scoring when you have these deadlines where it’s just the first thing you think of, whatever your gut reaction to something is, that gets to be what you put down.

GC:It’s just getting some words together very quickly and all the rest of it, so it’s almost like automatic writing. You’re not thinking too much about it, so maybe it plumbs the depths a little more.

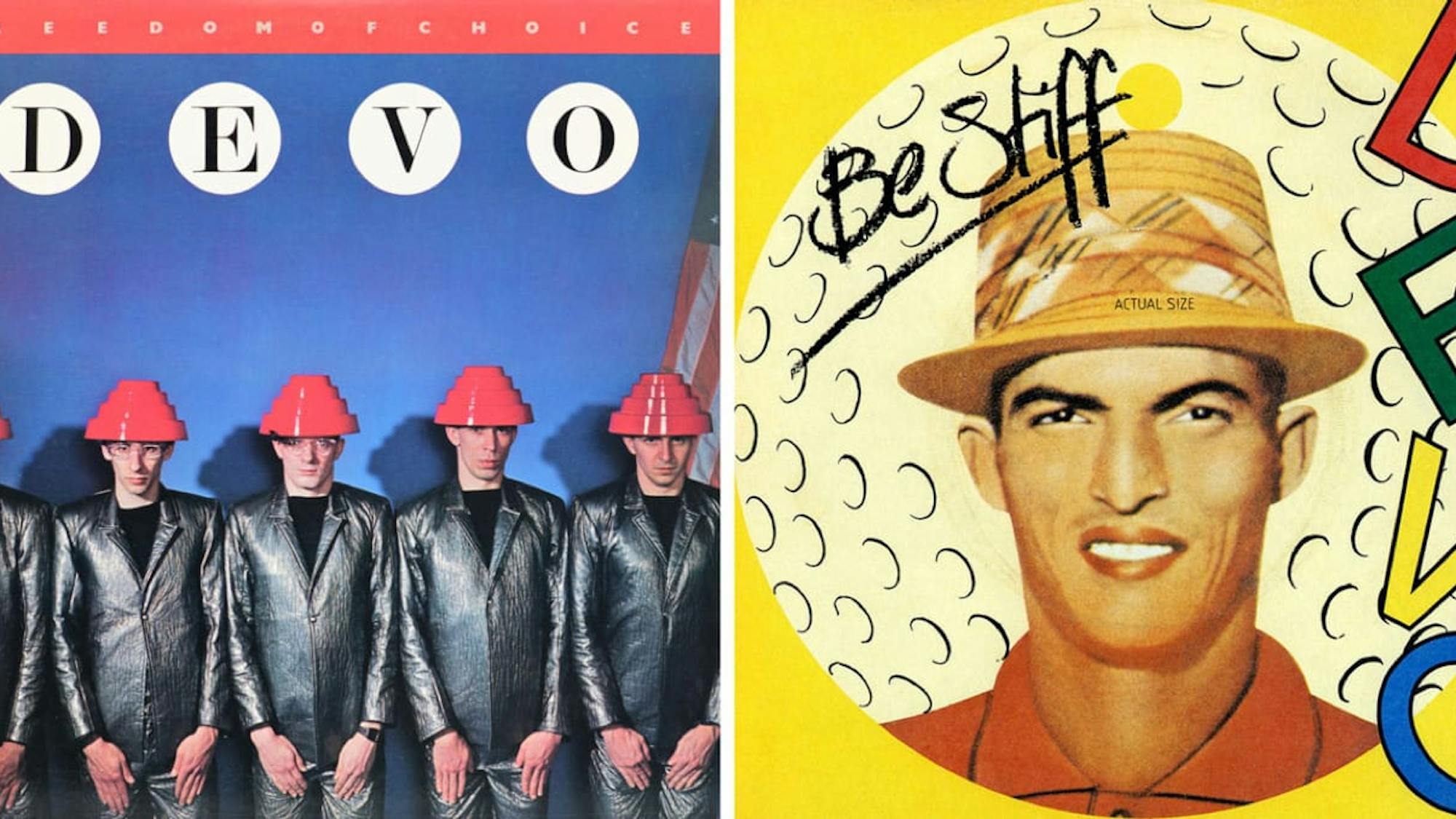

Devo albums Freedom of Choice and Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo!

Freedom of Choice by MPVCVRART / Alamy Stock Photo; Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo! By Records / Alamy Stock Photo

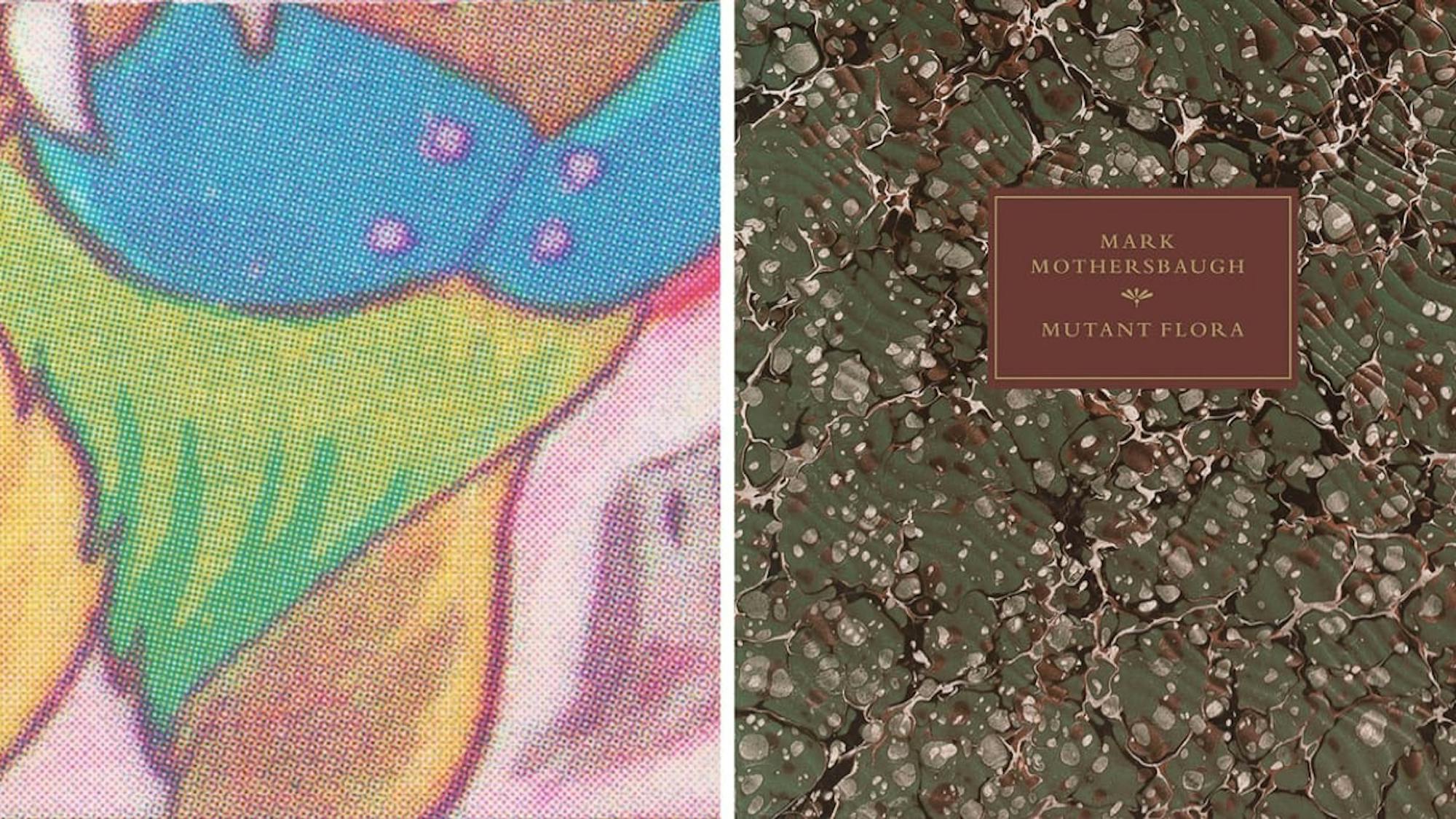

Muzik for Insomniaks Volume 1 and Mutant Flora, solo works by Mark Mothersbaugh

Muzik for Insomniaks Volume 1 © Enigma Records; Mutant Flora © Mut Muz

MM: I think there’s a lot of overworked music out there. There’s a lot of music that people think about too much. It loses what you’re talking about: the ability to almost stream-of-consciousness make something.

GC: I absolutely agree. One of my favorite Beatles eras is Rubber Soul. There’s this YouTube video, “Why Is This Beatles Song So Messy?” It’s “I’m Looking Through You,” and it goes over all the bits that I love about that song. It’s all the little whistles of feedback here, and someone slapping their thighs, and then they stop in the middle of a sentence. It’s just a mess. I suppose these days you call it ear candy, but for me, those sounds are the beginnings of psychedelia. They’re things that your ear picks up on, and it makes the experience a lot richer.I still think the recording process is incredibly magical. To me, it’s still absolutely magic that these things come into existence over the course of a day, and there’s this new thing out there in the world. Almost like a spell.

You sound like somebody I’m going to be a fan of.

Mark Mothersbaugh, to Graham Coxon

How did you come to work on your latest Netflix projects, I Am Not Okay With This and The Willoughbys?

GC: With I Am Not Okay With This, it was through Jonathan Entwistle, who created The End of the F***ing World. What was cool about it is that I went a little further than the brief. There is a band that’s within I Am Not Okay With This, called Bloodwitch, and I think there’s only four of their songs in the show, but I thought, This would be cool if I actually treat this like a real band, they have a sort of chronology, and this is an album. So I made an 11-track album by Bloodwitch, a few songs from which are featured on the show. They had to be a cool, not very well-known amalgamation of all the indie bands I really liked in the mid-80s, like The Jesus and Mary Chain, and Talulah Gosh, and My Bloody Valentine.

MM: Hey, I’m waiting for the double-album set where Bloodwitch does an album full of Blur music, and Blur does an album full of Bloodwitch. I heard that’s coming up soon.

GC: That sounds like a lot of work.

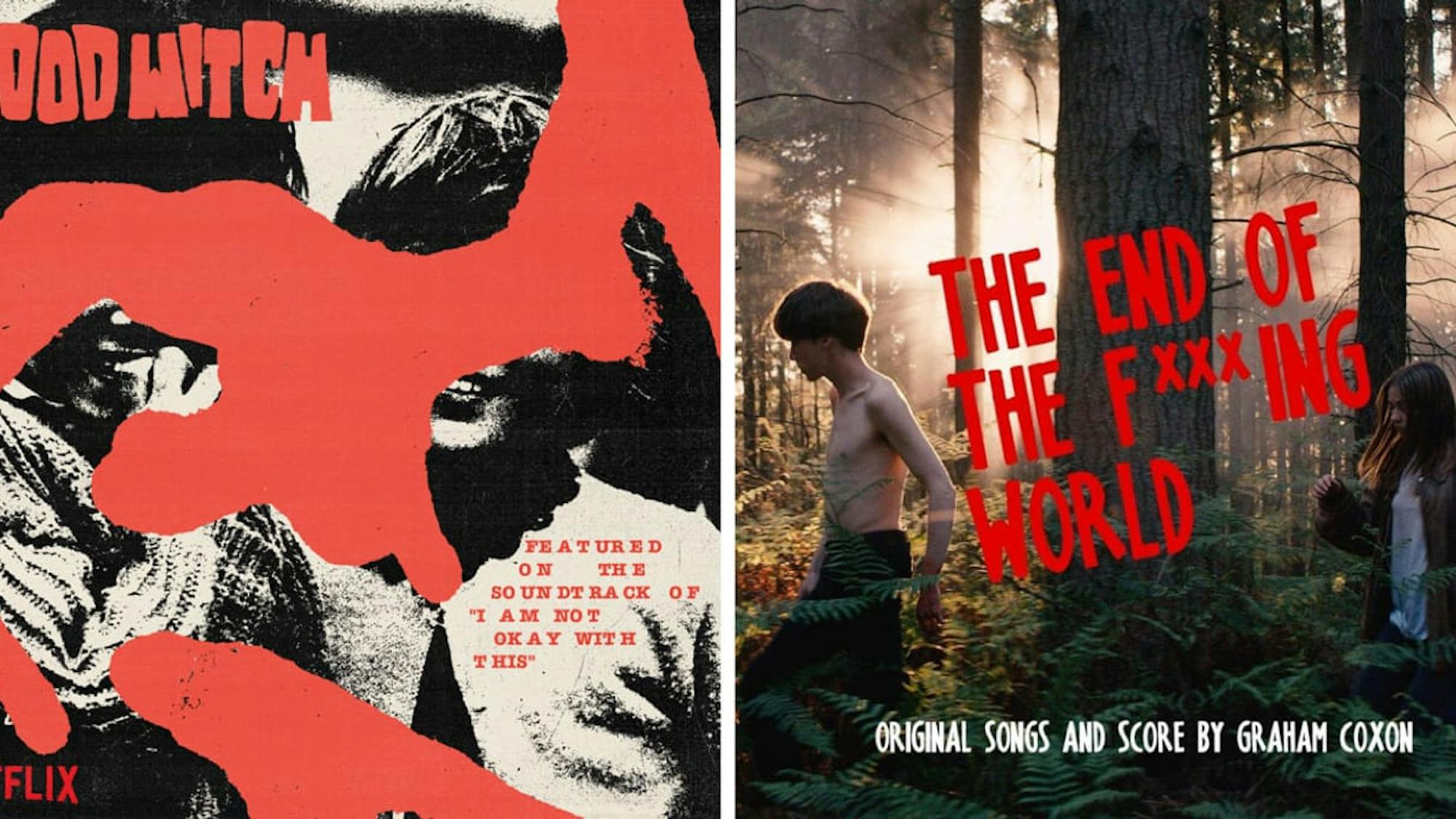

Graham Coxon’s albums for I Am Not Okay With This and The End of the F*ing World

MM: The Willoughbys, what happened there is that there’s a guy named Kris Pearn whom I worked with on a movie called Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs, and this was a project of his. Since we’d already worked together, he thought, Well, let’s call Mark and see what’s going on. In The Willoughbys, he had this great animation style that had a 60s-Brit look, and it just lent itself to having different musical stylings. There was a crazy candy-factory character who worked really well with electronica. The family in the movie lived in this 150-year-old house in the middle of some big metropolis somewhere, in between two skyscrapers, and they had this little dilapidated house that lent itself to a very intimate jazz quintet or sextet. I did that in the style of things I’d done for Wes Anderson. And, of course, it’s animation, so you need your big orchestra somewhere in the film. We recorded it in Abbey Road Studios; that’s kind of my go-to place for orchestral music.

Mark Mothersbaugh’s albums for Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs and The Willoughbys

GC: There’s a little scene around halfway through I Am Not Okay With This where they’re planning how to get this thumb drive out of a video camera. One of the characters says something like, “I’ve got a plan, and this happens and this happens, and we put the burritos in the microwave, and bang and this!” — and there’s a piece of music that I had written that was totally influenced by your Life Aquatic score. It starts off like a tiny drum machine, really simple, and then by the end it is huge — the arrangement has gone so vast and wide.

MM: I’ll probably hear your music temped in for my projects in the future now.

GC: That would be so weird.

MM: It’s shorthand, though. I understand. It helps them talk about music in a way that words can’t cover.

GC: Absolutely. It says the whole paragraph without having to talk.

MM: Well, I’m going to stalk you on the internet a little bit and get into everything you do. You sound like somebody I’m going to be a fan of.

GC: Oh, brilliant! Let’s research each other.

MM: Or stalk.

GC: Yeah, I think it’s maybe stalking.