The star at the forefront of the past decade of entertainment discusses playing Margaret Thatcher on The Crown and sex therapist Jean Milburn on Sex Education.

Consider it a testament to Gillian Anderson’s power that she can inhabit our collective cultural imagination as the outspoken sex therapist Jean Milburn on Sex Education and, at the same time, give a showstopping performance as conservative icon Margaret Thatcher in The Crown Season 4. “It feels like a really good moment,” says Anderson of her current creative circumstances. “It feels like stuff is coming to me in a different way, a different capacity — some very interesting material and really interesting characters. It feels like the right time for it, and it is odd when that happens in one’s 50s. I’m trying to savor it as much as possible.”

Anderson entered the spotlight at age 24, when she landed her career-making role as F.B.I. agent Dana Scully on The X-Files. The show earned her an Emmy, a Golden Globe, and two SAG Awards for Best Actress — accolades that accompanied an overwhelming response from a die-hard fanbase. Her performance broke new ground for women in television, and Anderson fought hard for equal pay with her co-star David Duchovny. (Point of interest: There’s evidence — anecdotal and scientific — that her character has inspired women to pursue careers in STEM fields, a phenomenon known as the Scully Effect.)

Over the years, Anderson has delivered a series of striking performances onstage and onscreen. There’s her leading turn in the 2000 adaptation of Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth, her Emmy-nominated work in the BBC miniseries Bleak House, and her chillingly glamorous portrayal of Detective Superintendent Stella Gibson in the Northern Irish crime drama The Fall. That’s in addition to starring roles in productions of A Doll’s House, A Streetcar Named Desire, and All About Eve, each of which garnered her a Laurence Olivier Award nomination.

The actor, a bold feminist from the early days of her career, also maintains a hilariously naughty Instagram account. Broadcasting to her 1.8 million followers, Anderson celebrates, among other things, the genitalia-themed imagery that Sex Education fans send her way. “Most of the time it’s people who send stuff to me, and I will repost it and draw attention to it with a quip of some kind,” she says. Margaret Thatcher would definitely not approve.

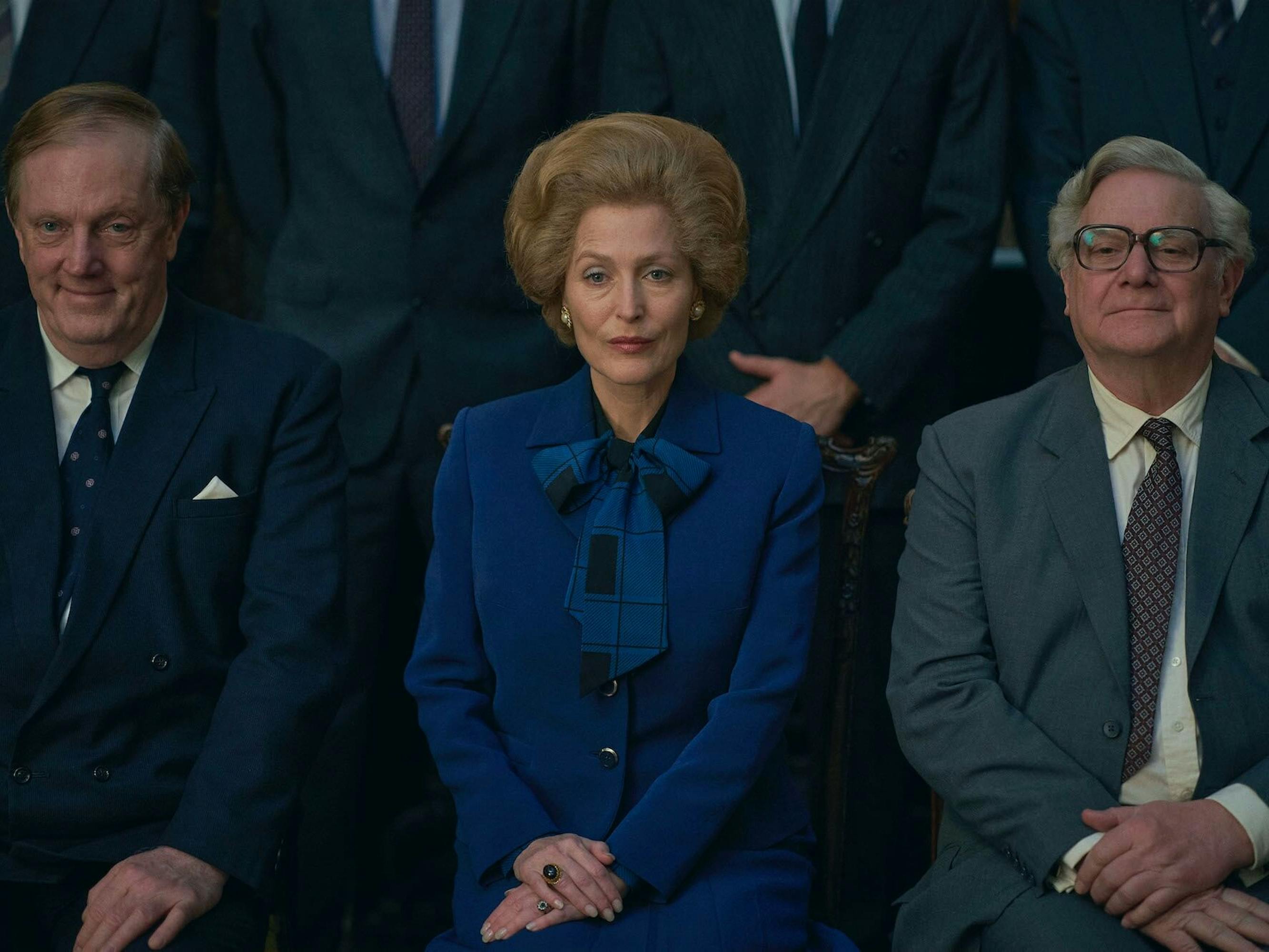

Margaret Thatcher (Gillian Anderson) and members of her cabinet in The Crown

Krista Smith: This performance is a tour de force. What was your way into playing Thatcher? Was it the voice?

Gillian Anderson: The way in felt like it was through the voice. It took a lot of work and a lot of time before I felt confident to let it out of myself. You can have all the other bits — you can have her profile, you can have the wig, you can have the movement — and if the voice is not right, the audience will be uncomfortable; they won’t buy it. It’s also getting to a point where you feel like you have the voice within the specific lines and, at the same time, can walk like her and move your arms like her and tilt your head like her. In our first week of filming, three or four times it was like, Oh, there she was! and then, Oh, nope, lost her. As you play her for longer periods of time, you get deeper into her shoes and feel like all the bits are working simultaneously. You feel like you are living in her skin for longer periods of time.

Thatcher was such a polarizing figure, with so many contradictions. One minute she’s a hard-ass, and in the next scene she’s cooking dinner for members of the cabinet. She’s irate that someone else is going to unpack her husband’s suitcase.

GA: So much of who she was stems from her childhood and her father being an alderman. They were Methodists, and religion was a big part of their daily lives. She was a grafter, but also learned how to make a home, and how to iron, and how to do the things that women did for their husbands. So much of her personality you can see in pictures of her standing next to her father while he was speaking. She’s so self-contained. At the moment she found the Conservative Party, while she was in college, she found a voice — she found that place where she could express what was already percolating inside of her. On the one hand, yes, she was a woman, and she was prime minister of Great Britain for 11 years, and that’s no small thing. But she did not support women. She did not help women up the ladder. She wasn’t really interested in helping women up onto an equal footing.

Margaret Thatcher (Gillian Anderson) and Queen Elizabeth (Olivia Colman) in The Crown

The scenes between you and Olivia Colman as Queen Elizabeth, when Thatcher and the queen have their weekly audience, are mesmerizing.

GA: I was dreading the audience scenes the most because there were so many words, and it felt like there were so many of them. I mean, Olivia was amazing to work with and incredibly patient. They were fun, but daunting to prepare, daunting to figure out how to make them different, daunting to figure out how to make them interesting. I assumed that they would be people’s least favorite scenes, that they’d get bored of me as Thatcher quite quickly. I was very surprised when I heard people saying afterward that those are some of their favorite scenes. I literally could not fathom what they were talking about. I was so terrified of them, and they felt so stressful.

People might not realize this, but you mostly lived in London until you were 11, and then your family moved to Michigan. You’re a preteen, you’re in the heart of the Midwest, and you have to fit in and figure out who you are. How did you choose acting? What about it made sense to you at that time in your life?

GA: I don’t know. We’d made the move from London to Grand Rapids, which was always going to be temporary. Even though my parents were Yanks, I felt British, and we still had a flat in the U.K. For some reason, I decided to audition for a community production of Alice in Wonderland. As a kid in the U.K., I’d done bit things in the Christmas special and all that kind of stuff, but I don’t think I’d ever expressed that much interest in it. I don’t know what propelled me to go for this audition. When I got there, it was a big civic theater. There were 250 girls my age who could sing and dance, and their dream was to do theater. I hadn’t done anything. I didn’t get it, and so I thought, Oh well, I’m not meant to do this. A few years later, I decided to take an acting class at the same theater. It so happened that the guy who was holding these classes was British and had been the director of Alice in Wonderland. When I showed up in his class, I’d now been in high school for two years and was speaking with an American accent. He said to me, “Wait, did you audition for Alice in Wonderland? And did you have a British accent?” I said, “Yes, that was me.” He said, “We wanted to cast you, but you’d never done anything. This was our big summer show; we couldn’t give it to a complete unknown. But we wanted to cast you.” That encouragement, that knowledge — the idea that there was something in there that maybe was good or watchable — helped me to pursue it and keep going.

Margaret Thatcher (Gillian Anderson) in The Crown

It is the story that keeps every actor breathing: coming to L.A. and doing grueling auditions. For you, one of those auditions happened to be for Dana Scully on The X-Files. She was this new kind of role model: smart, tough, practical, equal with the guy. Initially, you were told to stand behind David Duchovny, and you were like, Fuck that. I’m sitting next to him. And you demanded equal pay as the series went on. Talk to me about that.

GA: I guess it started to hit me around the third season. At first, he had just come off of that Kalifornia movie. His financial deal for the series was a financial deal for a movie star, and mine was for a nobody. So it made sense. Three years in, when we’re doing an equal amount of work, and the show is centered around a duo, it didn’t make sense anymore. We started to go back to renegotiate. One of the big moments was when we were going to do the first X-Files film. He was offered multiple seven figures, and I was offered something so ridiculous you couldn’t even believe it. I asked to have lunch with Peter Chernin, the chairman at Fox. After that lunch, he said, “She’s fifty-fifty.” I don’t know what it was that I said, but from that point on, it felt like there was no going back from expecting that. Cut to 2015 and 2016 — and I’m only bringing this up because it’s interesting what people try to get away with, not because I still necessarily have an issue with it — when we did a couple of extra seasons, and Fox tried it again, the same disparity between the two of us. I mean, what? It’s so weird — forget insulting and forget stupid. When we started to do press and somebody asked a question about the olden days, I was like, “Well, guess what? Some people still think it’s the olden days, but that doesn’t fly anymore.”

Fox Mulder (David Duchovny) and Dana Scully (Gillian Anderson) in The X-Files

Moviestore Collection Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

What was it like, at the age of 24, to try to navigate that level of fame? People were uniquely obsessed with The X-Files. You were part of their lives.

GA: On the one hand, we were protected to a degree because we were shooting up in Vancouver [for the first five seasons], which was a huge blessing. Both David and I ended up in Malibu and couldn’t be out and about without paparazzi. But also, I had a child. In the first season, I got pregnant. Everybody was quite furious, and I get it now as an adult. But at the same time, it happened, and she kept me sane. Having to show up as a parent and wanting to because of the love that I felt for her, she really kept me grounded. I would come to L.A. to do press around the Globes or periods of time when I was being nominated, and even though what she and I had was quite small, everything else felt so false and ridiculous. Having that perspective on the business saved me. Being caught up in nappies and breastfeeding saved me from getting lost. The stuff that I’ve been doing in the U.K. since The X-Files has brought its own level of attention. But doing something on Netflix is a different thing when it’s one of their top shows, and I don’t know if I had entirely thought that through. I certainly wouldn’t change it, but it is a different way to live. I forgot the levels of paranoia that one can get into about being looked at, talked about, and photographed on the street when one is out and about, which I have been free from for a while.

I have to ask: Did you take anything of Thatcher’s with you?

GA: For a while, I walked away with one of her facial mannerisms, which drove me nuts. I couldn’t seem to get rid of it for a couple months. I even took her into something I did in Sex Education for a little bit. I had to keep properly reminding myself, No, let’s do that again. Thatcher just showed up.

Jean Milburn (Gillian Anderson) in Sex Education

How do you feel about your work on The Crown now that it’s behind you?

GA: When people were starting to respond to it and were responding positively, I was kind of waiting for the other shoe to drop. But I feel relieved. I feel like it was the experience I wanted to have, beginning, middle, and end. I accomplished what I wanted to in terms of being able to track her trajectory within the context of the series in a meaningful way. I guess I feel that the hard work paid off. I did the best that I could do.

Charlotte Hadden