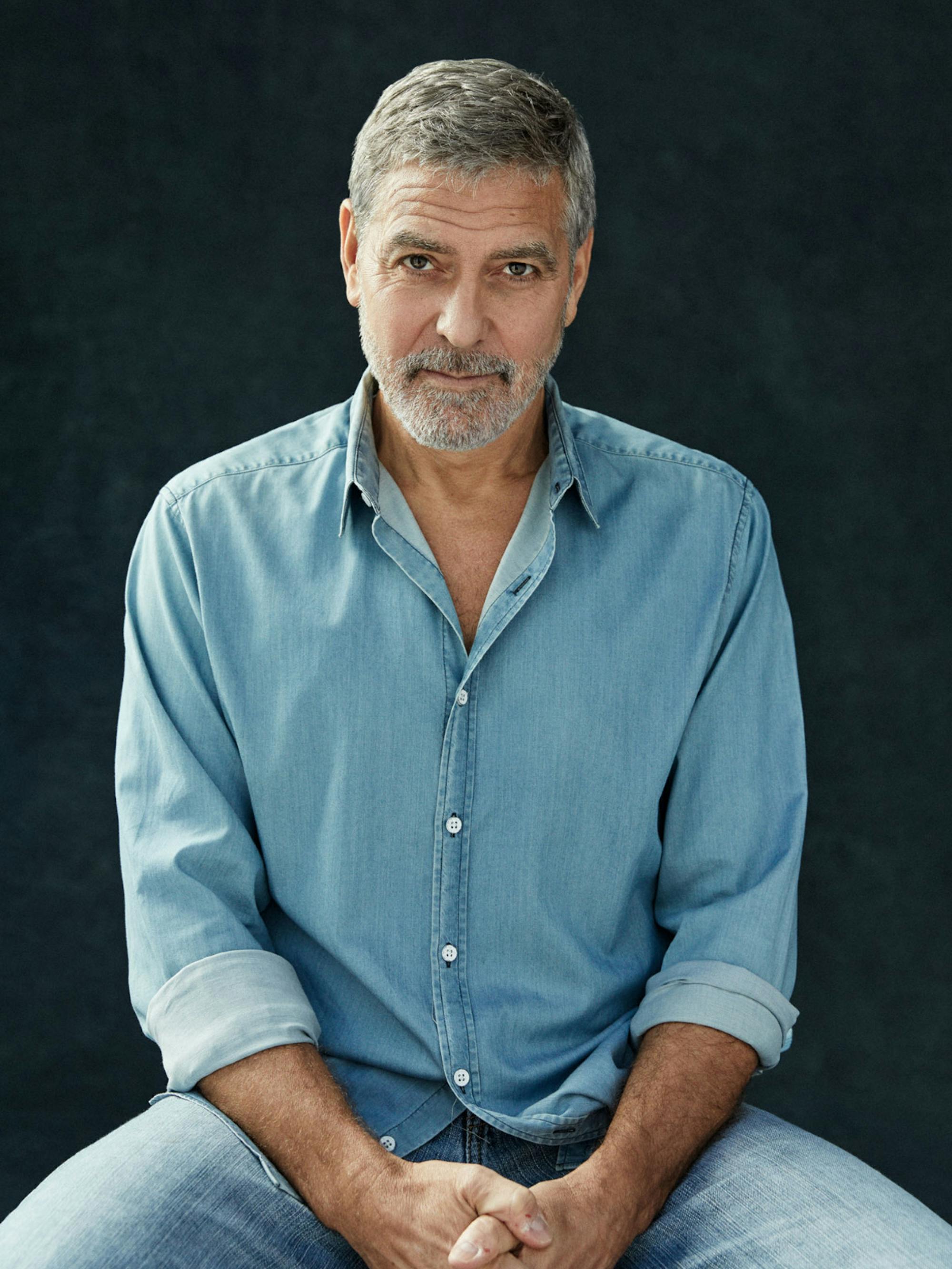

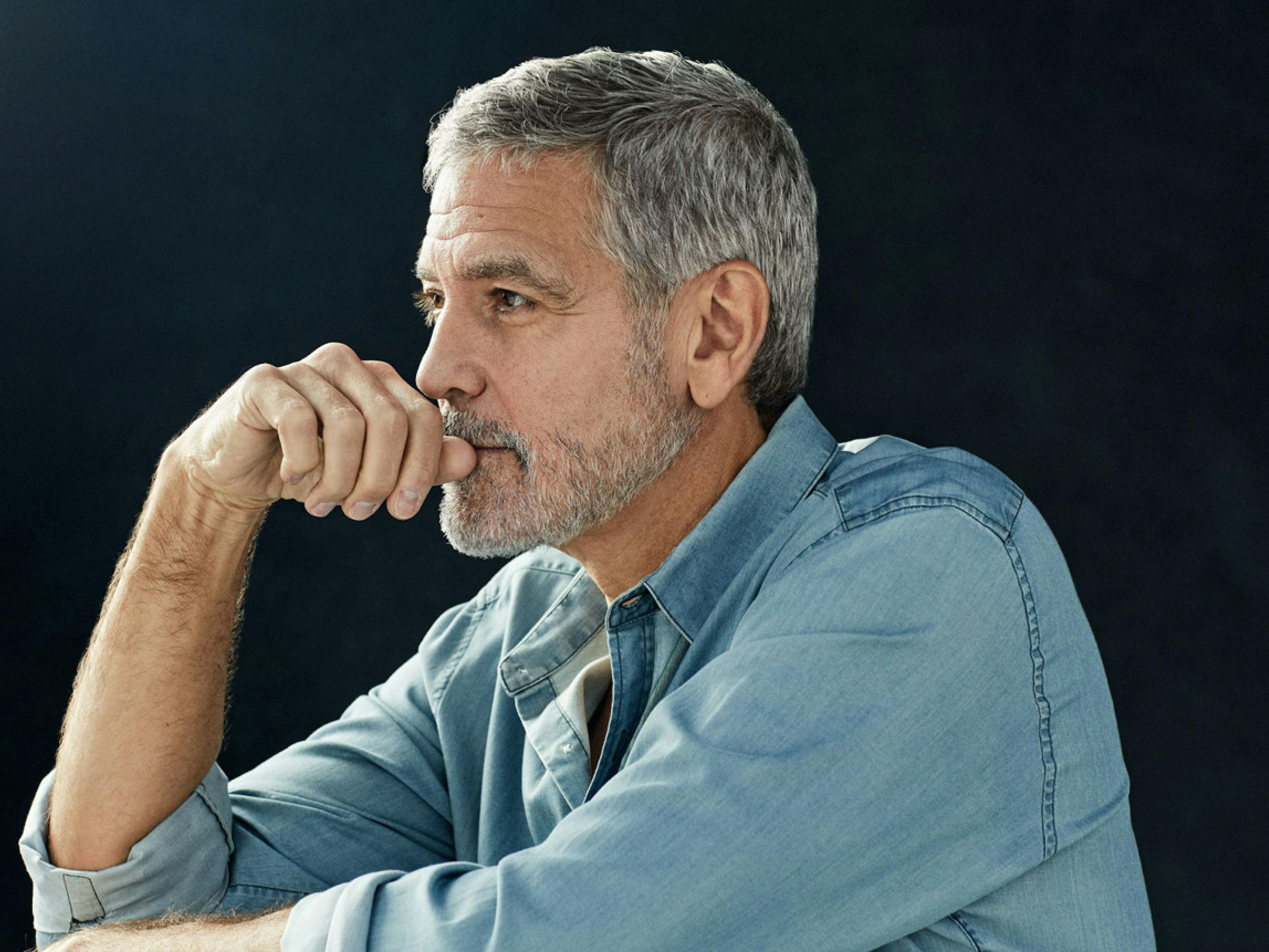

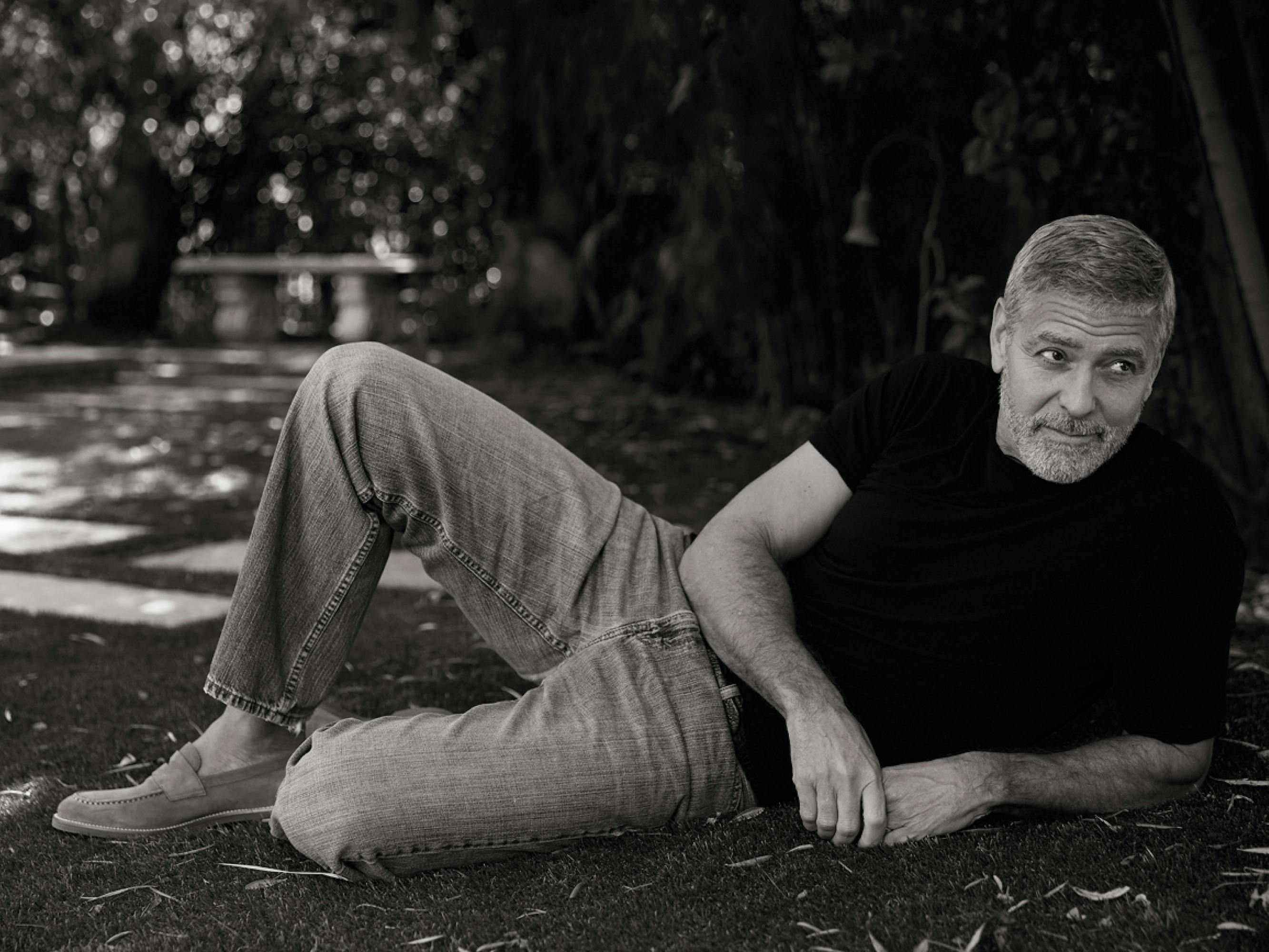

With The Midnight Sky, the actor-director takes on his most ambitious project yet. And that’s saying something.

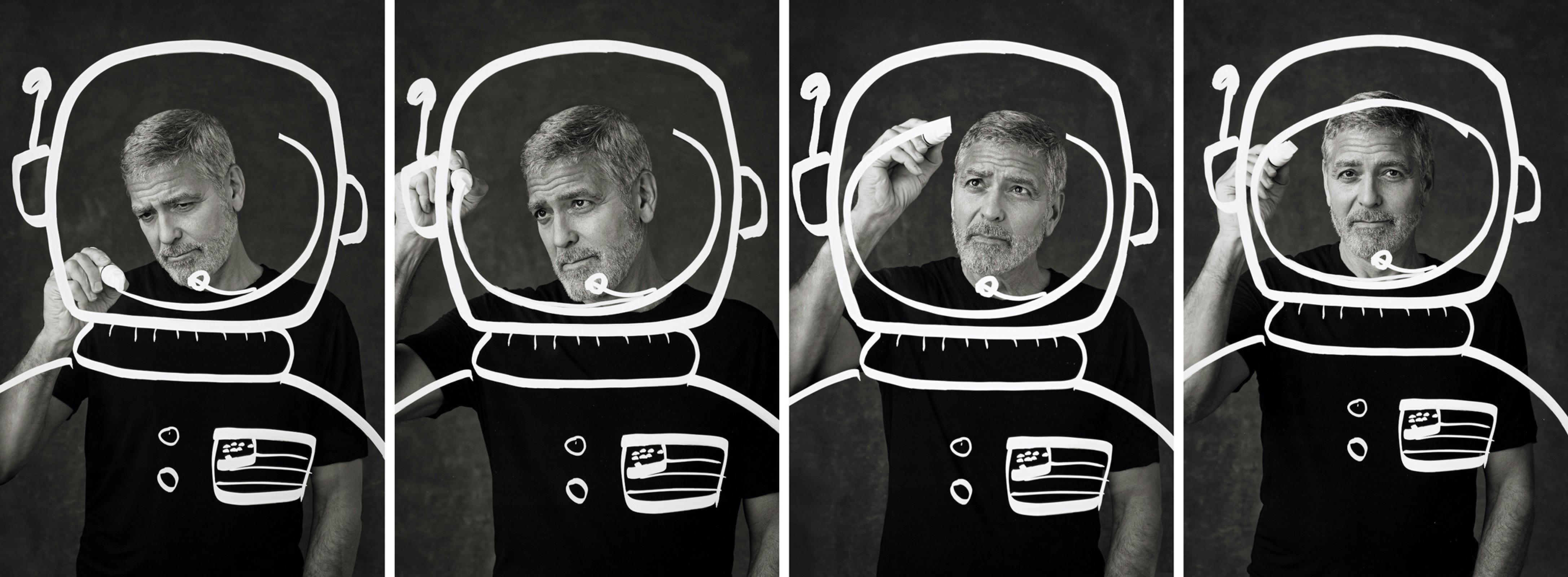

George Clooney’s new action drama The Midnight Sky begins with the end of the world. The year is 2049, and a team of astronauts is en route back to Earth. They’ve been exploring the life-sustaining capabilities of one of Jupiter’s moons, but global catastrophe strikes before they can return home. A lone scientist survives at an Arctic outpost, searching for a way to warn them.

Clooney, who both stars in and directs the film, sees uncanny parallels in contemporary society. “The inability to communicate from Earth to this spaceship feels very much like the things that we’re going through more and more,” he says. “We’re losing the sense of community. We get into our own worlds, and we stop looking out for one another.”

Based on the novel Good Morning, Midnight by Lily Brooks-Dalton and adapted for the screen by Mark L. Smith (The Revenant),The Midnight Sky marks Clooney’s return to cinema after a three-year absence, as well as another collaboration with producing partner Grant Heslov. He plays Augustine Lofthouse, the lone scientist remaining at the outpost. Lofthouse is terminally ill, and he’s profoundly alone — until an abandoned child, Iris (newcomer Caoilinn Springall), makes her presence known. He must protect her and save the Jupiter expedition from a dying Earth.

The film features an all-star supporting cast — Felicity Jones, David Oyelowo, Tiffany Boone, Kyle Chandler, and Demián Bichir — and stands as the most expansive production Clooney has yet overseen. He is more than up to the challenge, having long ago earned his stripes as one of Hollywood’s most gifted actors and filmmakers, not to mention one of its nicest guys.

After breaking through in the 90s as the TV heartthrob Doug Ross on ER, Clooney forged longstanding creative relationships with directors including Steven Soderbergh, Alexander Payne, and the Coen brothers. In 2006, he earned the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor, playing C.I.A. agent Bob Barnes in the geopolitical thriller Syriana. That same year, he cemented his reputation with the Oscar-nominated Good Night, and Good Luck, a black-and-white drama that he directed, starred in, and co-wrote with Heslov.

In the years since, he’s directed acclaimed films including the political drama The Ides of March and, most recently, the 1950s-set satirical thriller Suburbicon. He’s given celebrated performances in Michael Clayton, Up in the Air, and The Descendants, and brought his effortless charm to the Ocean’s Eleven franchise. He’s also lent his celebrity to a raft of humanitarian causes, from ending world hunger to curtailing human rights abuses.

The actor-filmmaker is now the father of twins and the husband of international human rights attorney Amal Clooney. He says that the environmental themes in The Midnight Sky were a key factor in his attraction to the project. Part interpersonal drama, part cautionary tale, the film imagines a bleak future, but one that Clooney believes we can avoid.“

If you don’t look at these bigger issues and take them on, then climate change is going to reach our doorstep; anger and hatred are going to come home to roost,” he says. “We need to find a way to remind ourselves that we’re all in this together. There is redemption in this film. The idea that none of us alone get out of this thing alive, but maybe as a group we get out of it intact — I think that’s important.”

Queue’s Krista Smith spoke to Clooney for her podcast Present Company.

Krista Smith: Is it fair to say you felt a sense of urgency driving you to make this film?

George Clooney: This was a great script. At the time that I first read it, there was no pandemic, but we were still dealing with hatred and anger. If you play out the impact of that plus climate change over 20 years, it’s not inconceivable that we end up in the same place that we are in this film.

I loved the challenge of space and the Arctic. I thought that those were two of the more difficult things to do in one film. And it was a story of redemption. I’ve always liked stories of redemption. Also, as a character, whenever you have a kid that you’re looking out for, you can be grumpy. It’s a bit of a free pass.

This movie is set in 2049. Usually when you’re watching a film dealing with the end of the world, it’s explosive and loud, and you’re on Earth. This is silent and vast, and seen essentially from space.

GC: This is more of a meditation on loneliness and on loss. I thought that it was an interesting thing to take out all of the sound and have it just be about emotion. There are long moments of just sitting with a child and watching her look at Polaris for the first time — things that I did with my parents that we don’t necessarily see anymore. I like the idea of silence. We have action in the film (I don’t want people to think it’s just a long, slow drag), and there are a lot of things that are funny and sweet in it. But they’re earned. You have to earn them by fighting with all of your other demons along the way.

This is the seventh film that you’ve directed, but the scale of it is enormous. What excited you about the prospect of making this film, and what kept you up at night?

GC: I was excited about all of it. I remember sending the script to Steven Soderbergh and he was like, “I wouldn’t touch this with a 10-foot pole.” He loved the script, but he just said, “You’re shooting The Revenant and Gravity.” That’s the way everybody puts it.

The elements, I knew, were going to be tough. I’d done The Perfect Storm; I’d worked in some pretty rough elements before. Space: I’d done Gravity and Solaris, so I had a real understanding of what those complications were. Gravity was incredibly helpful for the scale. We were shooting on 65mm, so it’s a gigantic scale. We were doing handheld shots with a 65mm lens! And trying not to copy anybody else is hard —Gravity’s done pretty damn well. There were tons of things that were intimidating.

Your co-star, Caoilinn Springall, is extraordinary.

GC: Almost everything I did with her was one take. She’d never acted before, and she’s brilliant in the film. I would go, “O.K., now you’ve got to be running away, and I need you to turn back with your scary sad face.” She’d run, turn back, and do this scary sad face. It ruins it for the rest of us who have to go through all this process before we can do it exactly right. She’s just like, I can do that. Having been on ER playing a pediatrician, I had worked with a lot of kid actors. The issue with kid actors is that they are trained by their parents on how to respond; they’re responding before you even ask the question. Caoilinn reacted in the moment in the way that the best actors do.

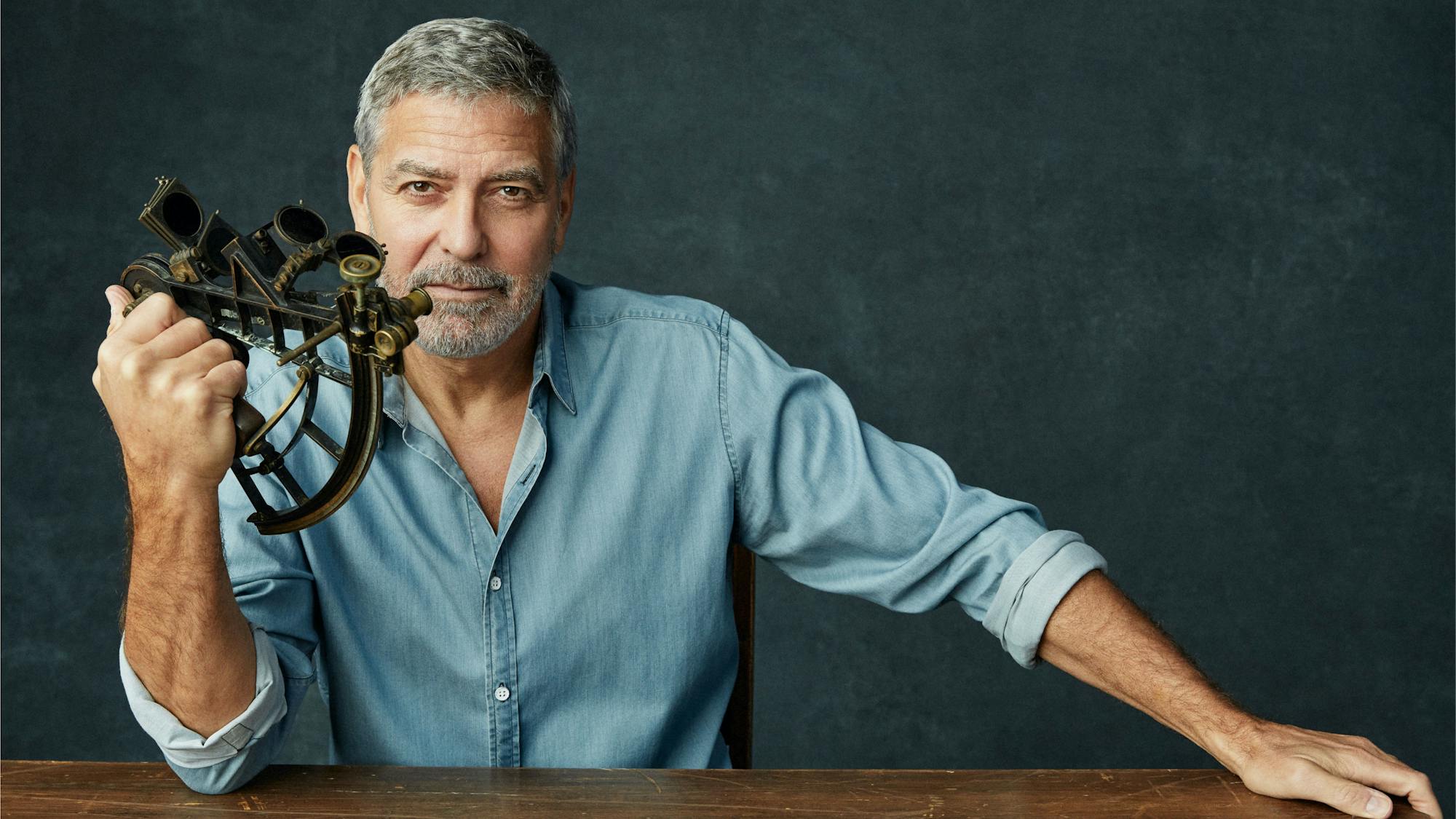

What is your favorite part of the day when you arrive on set as a director, versus when you arrive as an actor?

GC: As an actor, my favorite part is just walking on set in the morning, working with a director and the other actors, figuring out how you make this puzzle work — because it’s a puzzle, always. What you read in the script never is how it actually works. “Rome burns!” You have to figure out how to make Rome burn.

As a director, it’s figuring out how to get all of these different groups of people to realize your vision. I’m always over-planned. I have drawings of every single shot for the day so that we can work efficiently. It is an exciting thing to watch it come together. When Alexandre Desplat, who’s the composer for this film, goes to Abbey Road with the London Symphony Orchestra, they talk a language that you and I don’t understand. A half measure there and off a beat here. Then he just lifts up his arms and suddenly it’s a score, it’s music. That’s what it’s like when you’re directing, when it works. When the script works, when the actors understand what their role is, and when we’re all in it together, it’s such a beautiful moment.

You’ve had so many creative partnerships over the course of your career: working with Soderbergh, with your producing partner Grant Heslov, with Matt Damon, Brad Pitt, Don Cheadle... it goes on. What do you gain from those relationships?

GC: It’s a learning experience, always. Steven basically was my educator on film, on how to shoot: Shoot with a point of view; don’t just collect footage and decide in the editing room what the story is going to be. I’ve done four projects with the Coen brothers, which taught me how prepared they are, how precise they are. If I look at the guys that I worked with that I have such great respect for — Alfonso Cuarón, Alexander Payne, Soderbergh, Jason Reitman, these directors that I just absolutely adore working with — they love what they do. They get that we’re lucky to do what we do. They’re constantly growing and looking to stretch and try and fail, and that’s brave. All the people you mentioned, they constantly take chances and they’re constantly searching for something new.

When the script works, when the actors understand what their role is, and when we’re all in it together, it’s such a beautiful moment.

George Clooney

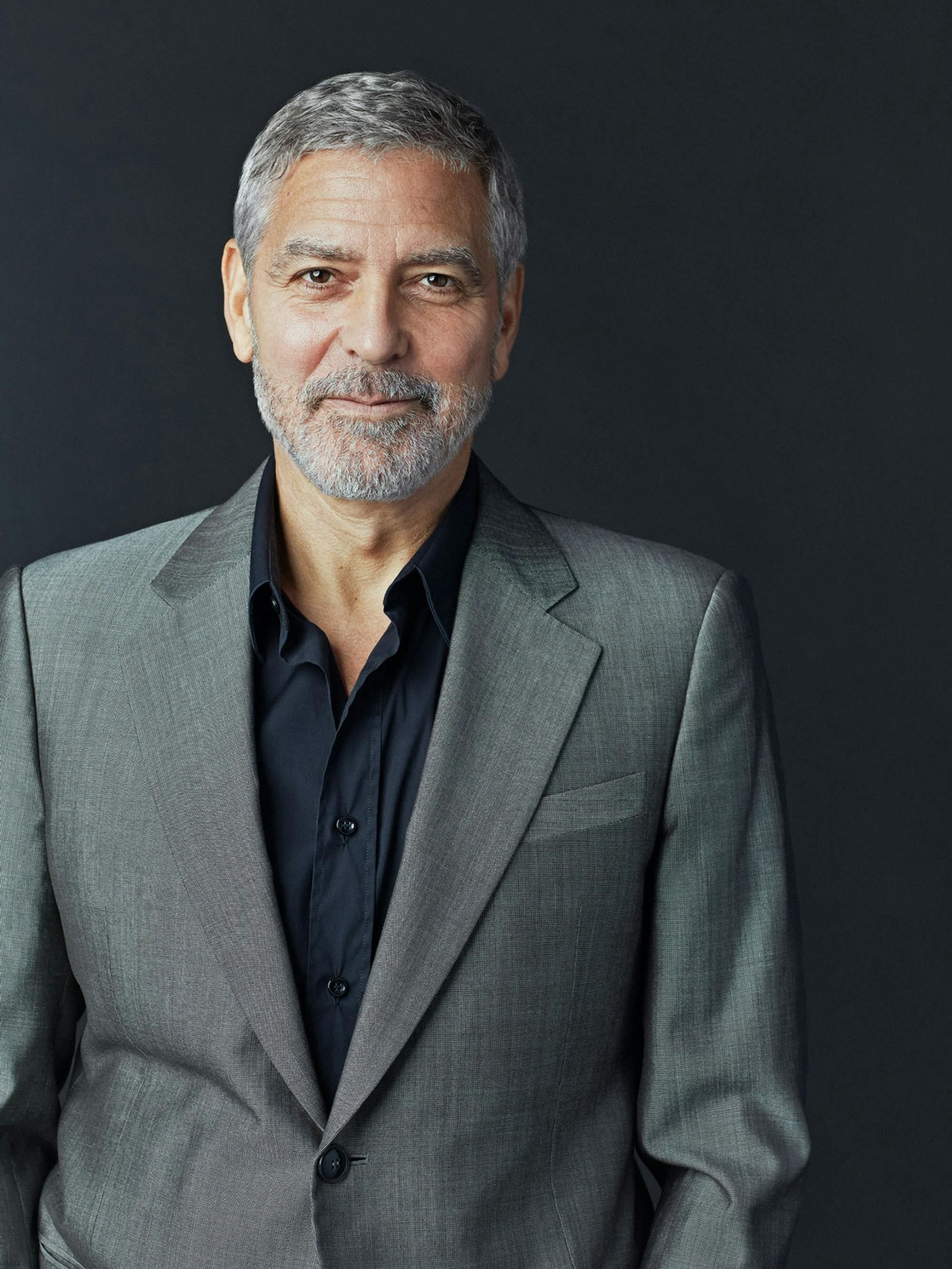

Has becoming a father changed your creative life? Had you not become a family man, would you have made The Midnight Sky?

GC: I haven’t acted in five years in a film. It was an active choice to try to spend as much time as I could with my children at a very specific time. They’re three and a half now, and it’s been a very exciting time to watch them grow up. Since I could, I wanted to be around — a lot of people can’t. I started very old, so I had an advantage. My mom was 19 years old when I was born. That’s hard, with no support system, no car, no nothing. I had these luxuries, the ability to say, O.K., I can take a year off and just sit with these knuckleheads and see who they want to be and watch the personalities that pop out.

It doesn’t change the kind of jobs I like to do. My daughter and son came to one sequence in The Midnight Sky, when I fall in the water. We shot in a tank, so I was in the tank, in a wetsuit with my wardrobe on top of it, and my wife shows up with my two kids. I’m shooting and I have to come out of the water and my character’s all upset because he’s lost this apparatus that’s going to keep him alive. My daughter’s like, “Papa, I want to come swimming with you.” Now every time I say I’m going to work, she thinks I’m going to a swimming pool.

With age comes perspective. Do you have a different relationship to success and to failure than you once did?

GC: Probably not, unfortunately. You would think you would get a little wiser about it. I’m always surprised at the failures, and oftentimes hurt by them. But I’m also a grown-up. I can look at things and go, Well, we’ll survive it. Nobody’s career is on a constant up. I’ve had things that have flopped, and with some of them you can feel there’s a rhythm that is missing. I’ve made fun of Batman & Robin for years and years. It’s a terrible film. I’m terrible in it. But the lesson that I got from that was: You’re now going to be held responsible for the movie. Before that, it was just: I’m an actor. I got a part. I’m going to play Batman. Fantastic!

As a result of suddenly being responsible for the movie itself, the next three films I did, I focused only on the script. The next three films I did were Out of Sight, Three Kings, and O Brother, Where Art Thou? and those were some really good screenplays and some really good movies. There is good to come from failure, and that is to understand where you have to take responsibility. You either sit in bed and put the covers up over your head, or you get up and go back to work.

You struggled for your success. You were that actor who had umpteen failed pilots. Then you hit with ER in your mid-30s. It was like a supernova.

GC: We got 40 million people watching that show. The big surprise was we were supposed to lose to Chicago Hope, and we ended up being the big winner. It was lucky for me because I was the oldest guy on the show. I’d done 13 pilots, and I’d done seven television series, so I had a real perspective.

When the first season hit, we did a lot of episodes because it was such a big hit. Everybody was tired. We were shooting six-day weeks. Once it was vacation time, everybody’s like, “I can’t wait to get this time off.” I got an offer for a movie, From Dusk Till Dawn. I was going to do that in my time off. I knew that there was going to be this one moment. I knew when it was hitting and it was going well for me, and I thought, I’m not going to step off of this train until somebody pushes me off.

For the next five years, I did seven or eight films while I was doing the show, which meant I worked seven days a week for about five years. It was exciting. The first real hit was The Perfect Storm, which had absolutely nothing to do with me. It was a big giant wave that was the star of the movie. But since I took so much shit for Batman & Robin, I took the credit for that one.

You’ve often stepped out of the spotlight to bring attention to causes that matter to you: the environment, the situation in Darfur. You’re an actor and an activist.

GC: I grew up in the 60s. You participated in things. We paid attention to civil rights and women’s rights and the Vietnam War. My father made it a point when I was a very young kid to say, “Always pick fights with people who are more powerful than you, and always look out for people who are less powerful.” Period. If there’s anything I was taught in my household, it was that. I believe in it. I think it works. It’s not always the most comfortable position. There were plenty of times when my father would get angry at somebody and I would go, “Can’t you just ignore it? Can’t you just let it go?” Now, I’m proud that he didn’t.