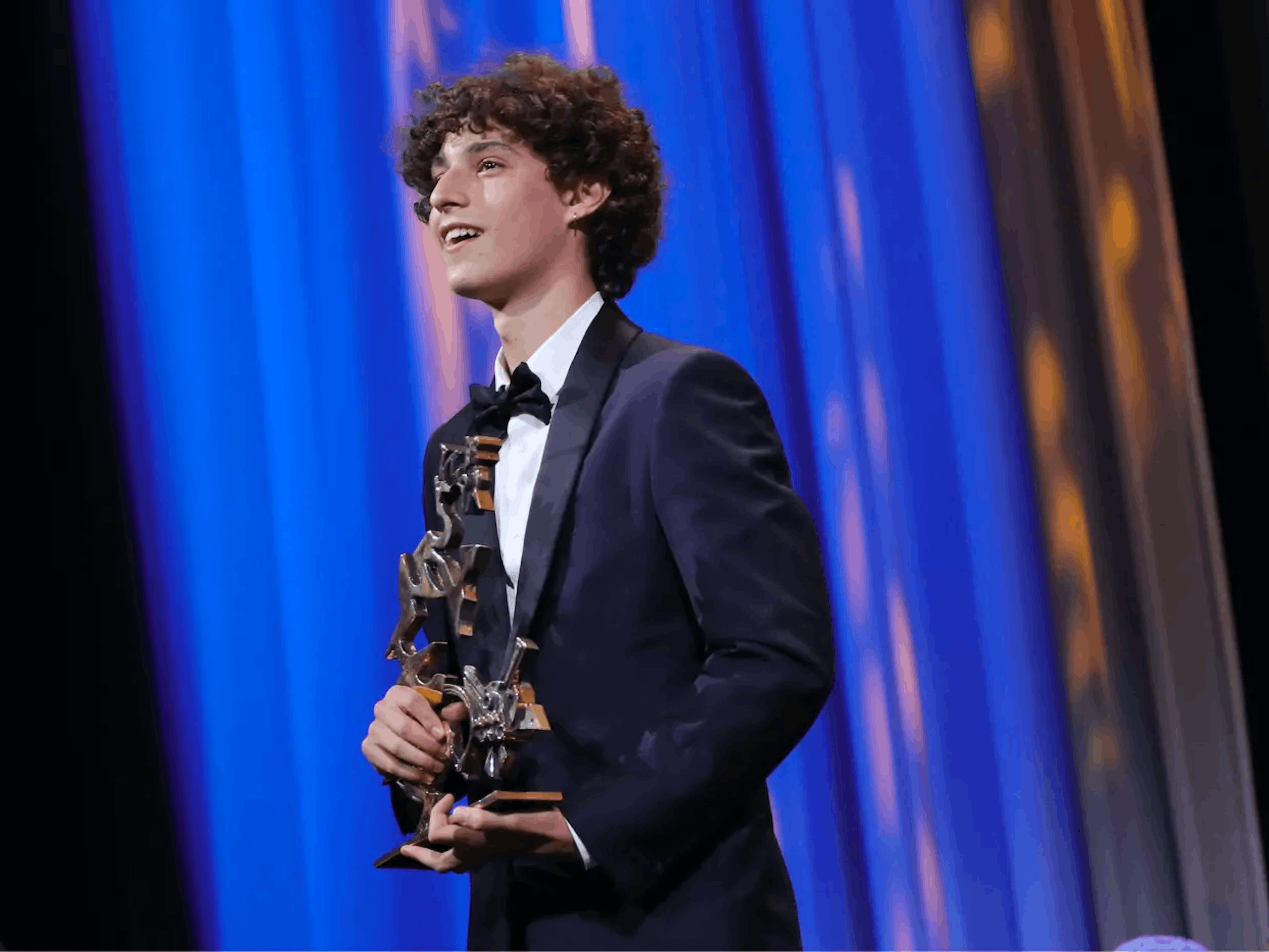

Meet the recent winner of Venice Film Festival’s Marcello Mastroianni Award for Best New Young Actor or Actress (joining the ranks of Jennifer Lawrence, Diego Luna, and Gael Garcia Bernal) as he discusses his work in Paolo Sorrentino’s The Hand of God.

Filippo Scotti did not want to go to sleep. He was eleven years old and it was getting late in Naples, Italy. He could head off to bed, or he could join his father on the couch to watch Rear Window. Filippo thought it might be a bore, but nevertheless, he chose Hitchcock. That night, a love of cinema blossomed and an actor was born.

Fabietto Schisa did not want to go to Roccaraso. His parents were off to their holiday home in the central Italian town, but football legend Diego Maradona’s Napoli team was playing against Empoli, and Schisa had season tickets, so he would stay in Naples. So begins the tragedy that unfolds for the teenage Napolitano character that Filippo Scotti inhabits so beautifully in Paolo Sorrentino’s coming-of-age film The Hand of God. Over the course of Schisa’s youth, he grows through devastation, he observes every detail of life around him, and he, too, discovers a love of cinema.

Scotti, who grew up in Dongo in the north of Italy, was brought up in Naples from the time he was six and started acting in theater productions before his love for film developed. “There was a small theater in the historic center of Naples,” Scotti recalls of his first acting experiences. “My mother proposed I start acting there. I was like, Why not? I can do this. That was the beginning, but it was just for fun. And it’s cool because this job is actually a bit like that. I mean, you have to study a lot, to focus a lot on the work, the project, and the character, but without enjoying it, it’s pointless.”

His first role in the theater came at age ten when he played a young prince. It was only a year or so later, on that fateful night when he watched Rear Window, that he started to envision acting as a career. “I was shocked by the beauty of that movie, the cinematography, and the actors. From there I started to focus on Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, and other directors that opened my mind way more. I was like, Okay, maybe I can do this for life.” As he dove deeper into the troves of great cinema, he began to admire the careers of Willem Dafoe, Paul Dano, and Mathieu Amalric. Throughout his adolescence, Scotti pursued acting and received his first professional paycheck for a stage production in 2016.

It was three years and three short films later that Scotti was cast in Netflix’s third Italian series Luna Nera, a 17th-century-set witchcraft drama. Being on the set of a large production was a new step in Scotti’s career, and he soaked up all that he could. “To see the machine — the cameras, all the people working around that place — was kind of shocking. So many people for a thirty-second scene! It was nice for my acting because I spent a lot of time on set, and it was my first time with that. I needed to prepare my body for these long periods of shooting. I was like, Okay, I need to go to sleep soon. I need to eat better.” This focus on honing his craft prepared the then-teenage Scotti for what would be the role of a lifetime.

Paolo Sorrentino is a name cherished not only by the Italian cinema community, but by film fans across the globe. The Naples-born writer and director has delivered unforgettable stories and breathtaking visuals through films like Il Divo, Youth, and Oscar-winner The Great Beauty. Sorrentino returned to his roots in Naples, and his own experiences as a teenager, when creating The Hand of God. Integral to capturing the story of protagonist Fabietto was casting the right young actor to convey the emotional crux of the film. Filippo Scotti was ready.

“For the first casting, I received an email from my agent with two scenes from the movie. It didn’t specify the director, which I thought was strange.” Even without knowledge of the acclaimed filmmaker behind the project, Scotti felt stressed. He was called back after the first audition, and this time the director was revealed. “I had a meeting with Paolo and I could not sleep that night. It was the first time in my life that I felt like this.”

After several auditions, Scotti got the call from Sorrentino that he had landed the role. Immediately he jumped into the script. He ditched the holiday his parents had planned so that he could stay in Naples, “to live in this noisy city for the month of August.” He spent the month reading the script, not to memorize but to understand. “I wanted to empathize with the text, without thinking as much about memorizing the lines,” says Scotti. Sorrentino was there to offer recommendations for music (Talking Heads, The Cure; “It was an 80s summer for me,” Scotti laughs) and films (The Road to Perdition; “I remember that Paolo told me, ‘Please when you watch the movie, pay attention to Jude Law’s walk!’”) to help shape Fabietto, but it was the emotional weight of the tragedy Fabietto suffers halfway through the film that Scotti paid particular attention to during his preparations. “I didn’t live that experience, that tragedy, but that story moved me, became my tragedy. Each of us has something that has happened in our life that doesn’t make us feel very comfortable, that we have to come to terms with.”

When you read a good script, you cry, you laugh just reading it, and then you feel something in the chest. It’s like when you love someone. It’s a hurricane inside.

Filippo Scotti

Once Scotti arrived on the Naples set, he channeled the time he’d spent empathizing and exploring, and delivered a powerful performance with the help of his director. “The way that Paolo is talking to you, so straight and also so quiet, he is basically saying, ‘Don’t worry, I’m with you. You can do something bad; I can do the same. We have just to work together and to feel each other.’” Like the large Italian Schisa family depicted in the film, the cast and crew formed a tight-knit bond. Perhaps unlike the Schisa family get-togethers, Scotti describes the atmosphere on set as organized, with everyone “listening to each other very much.”

Even with the confidence of his director and the camaraderie on set, there were still difficult moments to shoot. For Scotti the scene that comes to mind is when Fabietto loses his virginity to an older woman, The Baroness (Betti Pedrazzi). “When I read that scene for the first time, I was so excited. I was waiting for something like this. And it was such an honor to work with Betti. But it was difficult; it was a bit embarrassing. We were in this small room all together with masks on because of COVID. The air was hot. Everyone was so close: the crew, the microphone, the camera. It was a bit strange. But now, after watching it, I like it. I’m satisfied.”

Fabietto grows from an observer to a participant in life. “He learns that he must not disjoint himself, untie himself. Sometimes life is not good, not good at all. He learned not how to be a man, because he was a man already, but how to be brave.” Scotti’s own emotional education came while shooting a scene between Fabietto and his filmmaker mentor Antonio Capuano.

“It was 5:00 a.m. We were almost ready to shoot, everything was prepared, and Paolo was like, ‘Come here.’ He told us, ‘I want to see your truth. I wrote my truth, okay? But now I don’t care about my truth. I want to see your truth.’ I didn’t live through a tragedy like Fabietto’s, but this movie helped me a lot,” the now 21-year-old says. “It was kind of therapeutic. I learned that the past is the past, and sometimes we have to move on.”

For Scotti, Fabietto and The Hand of God are not to be moved on from, but to be remembered. Audiences at Venice and Telluride film festivals have found Scotti’s performance, and the film itself, enthralling. At Venice, the film picked up the Silver Lion Grand Jury Prize and Scotti won the Marcello Mastroianni Award for Best New Young Actor or Actress. Even before the accolades, Scotti knew that being a part of this project was something special. “My dream role is like this one; when you read a good script, you cry, you laugh just reading it, and then you feel something in the chest,” he expresses. “It’s like when you love someone. It’s a hurricane inside. I think my dream role is to play another role like this.”

Vittorio Zunino Celotto