Fear Street Part Two: 1978 star Ryan Simpkins and screenwriter Phil Graziadei discuss how the new saga fits into the canon of queer horror cinema.

In the past century, nothing has been quite like Fear Street: Never before has a major studio released a scary movie that features two lesbian leads whose romance is a central arc of the plot and who are given a fighting chance at survival. Fear Street isn’t a staid coming-out narrative or an old-fashioned horror story where the only queer presence is a monster that L.G.B.T.Q.+ fans relate to as marginalized “others.” This is not a horror story where the twist is, “Surprise! She’s a crazed homosexual killer!”

Fear Street does not punish its heroines for being gay or frame their queerness as the root of some evil. Instead, they are punished for being born in the blighted town of Shadyside, where a malevolent force has been wreaking havoc on the population for hundreds of years, and a few late-20th-century teens are fighting back to finally break the curse. It’s a classic 1980s slasher with the wry sense of humor of Kevin Williamson’s Scream. The blood flows generously. The kills will leave you breathless. But its emotional heart might also beat strongly enough to make you weep.

Through the saga’s first two chapters, Part One: 1994 and Part Two: 1978, director Leigh Janiak and co-screenwriter Phil Graziadei have delivered a raucous, brutal hack-and-slash adventure where your faves are never safe, but you don’t have to be worried about a gay bashing just because the leads are two girls in love. For queer fans of the horror genre, monsters have served as a powerful mirror for generations. From Frankenstein’s monster, to Dracula, to the Babadook, these characters have provided often times tragic, often times terrifying, but always mighty icons for queer folks to align themselves with in the absence of explicit representation. With Fear Street, it’s nice to have a few heroes to balance out the magnificent baddies.

“We’re really lucky to be writing in a moment where some studios and producers think it’s cool to make queer content. With Fear Street, we had the chance to do this overtly, and I want to make sure no one can say those aren’t queer characters,” says Graziadei. “I guess what I’m really saying here is: Big thank you to Netflix for putting these movies out there to such a broad audience, for taking what other studios might consider too much of a risk. In other circumstances, it’s just such a slog to get any queer content made. There are very few places for it.”

Queue sat down with Fear Street co-screenwriter Phil Graziadei and Part Two: 1978 star Ryan Simpkins (who plays camp counselor Alice) to talk about the queer D.N.A. of horror, from its gothic literature origins, to the importance of giving your queer fans hope, to a few subtextual storylines you might have missed.

Alice (Ryan Simpkins)

Did you read Fear Street growing up?

Phil Graziadei: No, I actually never read Fear Street when I was a kid. I was terrified by the covers because they were largely marketed toward a teenage girl audience, and a majority of the protagonists are teenage girls; at that point in my life as a closeted gay kid, I knew that if I picked that book up and someone saw me reading it after school, the number of times I got called faggot every day would explode exponentially. It would have effectively ended my life. Despite never having read them, they still occupied an important place for me psychologically, for that period of my life. Getting the chance to revisit them as an adult, when I don’t have the same kinds of anxieties, was a chance for me to go find that scared little kid in the bookstore, who didn’t want to pick up books that he thought he wasn’t supposed to like, and to say, “These are for you.”

When did each of you start to realize that there was this secret language in horror only you could see as queer viewers? When did you start to decode horror’s queerness for yourself?

Ryan Simpkins: I had a very similar experience to the one Phil just named, but with the film Jennifer’s Body. I was pretty young when that came out, but I remember seeing the posters everywhere with Megan Fox. There was this weird anti-Megan Fox thing going on that came from a place of internalized homophobia. The truth of it was, I wanted to watch the movie so bad. I was so curious about it. That movie was marketed to teenage boys, but in reality it’s this gorgeous, queer, fucked-up love story.

I remember I had this friend in high school who I was totally in love with. She was a major Jennifer’s Body fan, and I was afraid to watch it because I thought, “I don't know what that’s going to do.” I was so curious about it, and it remained in my brain for years and years. I only just watched it a few years ago, and I was suddenly like, “Oh yeah. I’ve been gay for a long time.”

Jennifer Check (Megan Fox) in Jennifer’s Body

Moviestore Collection Ltd / Alamy Stock

And you, Phil?

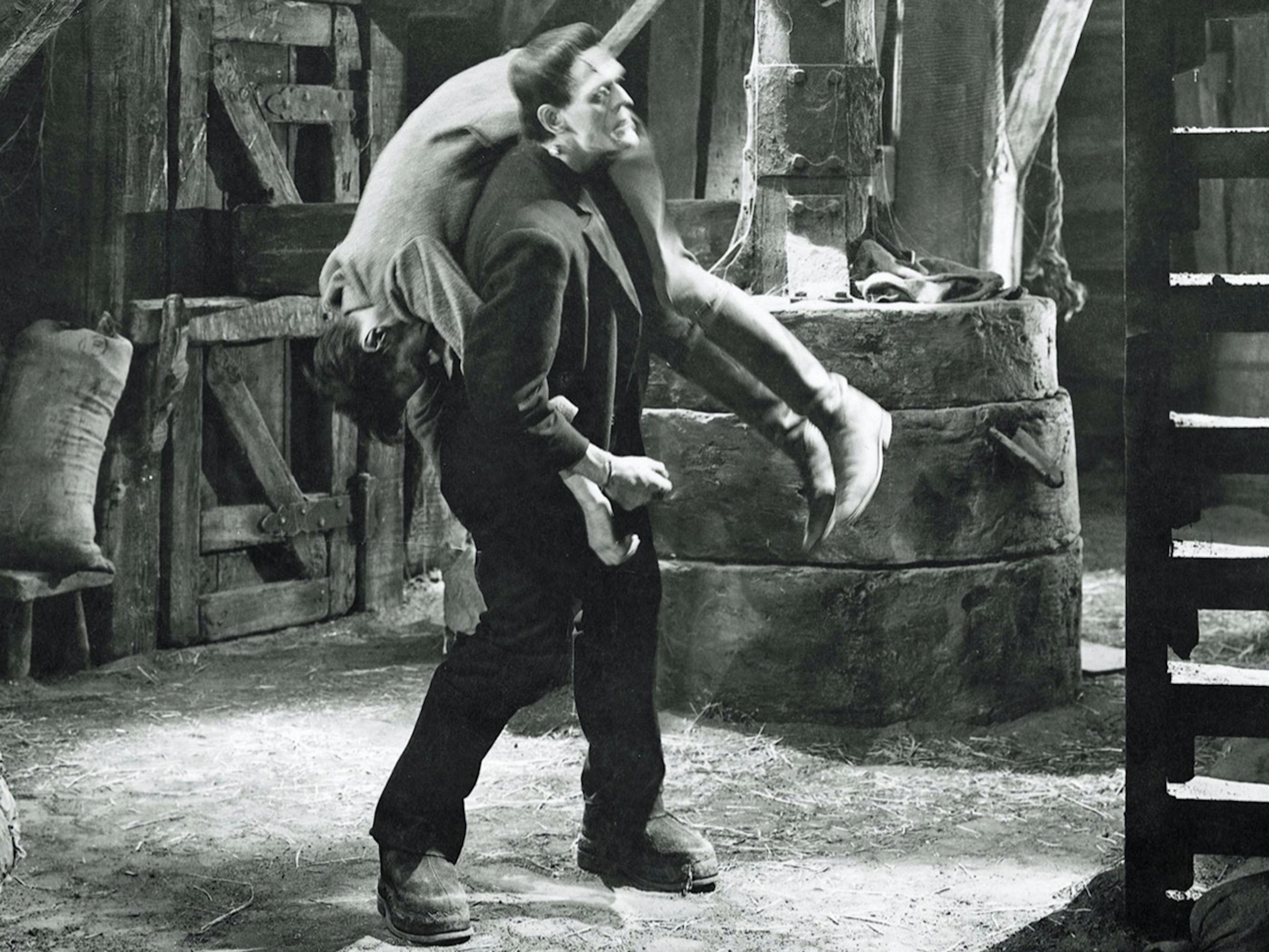

PG: To a certain extent, I think so many queer people are forced to live in the shadows in their everyday lives that they’re generally predisposed to seeing themselves lurking in the dark corners of horror movie subtext. The film that I think about immediately is Frankenstein. You go straight for that sympathetic monster; I guess I empathize with his loneliness. He’s this desperately lonely creature looking for a friend, right? I think that’s probably where it was for me.

RS: I remember reading Frankenstein in high school, and I was just livid. It made me so upset because I was empathizing so much with the creature. He was forced into society by his maker, then completely rejected by him, and then pushed to the outskirts of society where he had to socialize himself. I was always so frustrated because it was just a matter of taking the time to nurture this creature. There’s a beautiful chapter where he spies on a family and learns to love through witnessing them, which I feel as a queer person watching movies. No one in my family is queer. I never wanted to talk to them about it, and I didn’t have many queer friends growing up. You really do turn to cinema, and Frankenstein hits home.

PG: That section on the education of the monster, it does really speak to this quintessential part of queer experience, that we’re generally born into families where we’re basically alone. You’re raised with the same sorts of values and ambitions as the rest of your family, and then, for too many queer people, the second the truth about who you are becomes apparent, you’re told that you can’t be part of that community. That’s exactly how Frankenstein plays out. Once the monster works up the nerve to say, “I’m going to go introduce myself to these people. Surely they’ll see how much I care about the same things that they do. Surely they’ll accept me,” of course, they do not.

Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive) in Frankenstein

Cineclassico / Alamy Stock Photo

As the bearers of this story in Fear Street, what do you see as your responsibility to the monster, a figure that has so often been the avatar for queer horror fans?

PG: First of all, I don’t want to come off like I’m saying there’s only one way to do queer representation. Because there’s not. That shouldn’t be the point. We’re in a big community. For me, though, at a certain point, I think about only seeing myself represented on screen as either a victim or a monster — or if I’m really lucky — a combination of those two things. Maybe I don’t want to be the monster all the time in horror movies. I think it’s really important for everyone — especially queer people — to see stories where queer people have some sort of chance of being happy, especially in a genre that’s as intrinsically queer as horror.

RS: When I first started reading the script for Part Two: 1978, I didn’t immediately recognize Alice as queer. I was like, okay, let’s work out the relationship with the boyfriend. I was really stuck on this boyfriend thing, and I was like, “I'm not connecting with that.” Then she started coming together visually, and I was like, “Wait, are people going to think she’s gay?” As I continued to work through Alice and her motivations, I kept coming back to Cindy (played by Emily Rudd) and thinking, Oh, there’s this romance here. I kept trying to deny that within myself, which was crazy, but I kept coming back to that feeling and struggling with it a lot.

PG: Well, you’re in the fortunate position of having a writer who’s not going to tell you your character’s not queer.

Alice (Ryan Simpkins) and Cindy (Emily Rudd)

RS: I had a queer friendship when I was really young, before I understood that I was queer, and before my friend also understood that she was queer. But it was totally the foundation of our friendship. We understood each other as this “other.” We had so much joy just being together as we were: these weird, little, androgynous things. It wasn’t romantic at all, but it just felt like this shared recognition. People grow and change, and she started being really pressured by heteronormativity and started becoming a lot more feminine and girly, and I was heartbroken. I was furious, and it destroyed me. I felt like I lost a friend completely, even though she’d done nothing wrong to me.

That's the thing of this movie: It’s like Sam going to Sunnyvale or Cindy trying to appear more Sunnyvale-ish. I know that’s not who you are. In my case with Alice in Part Two: 1978, I do think there’s also some romance there, and it was nice because it wasn’t in the text itself. I didn’t feel a pressure to perform queerness in a certain way. It came out so naturally, and it was really beautiful. I never actually talked about it with Emily or with Leigh because I was really afraid they were going to say, “No, they're not gay,” or Emily was going to be like, “That makes me uncomfortable. No.” So I just kept it to myself. Then a month ago I was alone with both of them and I was like, “Hey, do you think Alice is gay? Do you think Alice and Cindy are... ” They were both like, “One hundred percent yes. Completely.” It was so validating that we were all on that wavelength. What’s so great about movies is that you can read from them what you will and you can interpret them any which way. Like, Is Alice queer? To me, yes. And to Leigh, yes. To others, maybe not.

Another important part of the Netflix conversation is accessibility, the ability of people to just press play on a movie like this without having to go through the trouble of finding it.

RS: I was never going to buy a ticket to see Jennifer’s Body in the theater because I was too nervous. Who was going to go with me? What questions would my mom ask? But if it were on Netflix, maybe before school, or after school one night, I’d be like, “I guess I’ll watch this.”

PG: One of the things that we wanted to do with Fear Street was to make the kinds of things that we didn’t have. So, having this kind of content at all, coupled with the idea that it’s just immediately accessible to people on a service like Netflix — I think for young, closeted queer kids, there’s this an age where you desperately need to see this kind of material, this kind of representation, but it’s tough to balance. If it’s not easily available to you, then you have to out yourself to get it, to some extent.

Tell me about wanting to put a sense of hopefulness in your horror movies, Phil.

PG: That was the whole point. We’ve talked so much about the state of queer representation in horror, and things that we’re doing differently in these movies. Queerness is still mostly a tragic victim of society, or a monster. So, it’s important for queer people to have that hope, to be able to get to the end of the first movie and to know these girls have a chance — they have a chance at being happy. But I guess I can’t make any promises about what happens by the end. It seems like Leigh and I like to kill people the second things get too good for them.

Sam (Olivia Scott Welch) and Deena (Kiana Madeira)