Producer and Black List founder Franklin Leonard asks Eric Roth about his career as a celebrated screenwriter and his experience producing David Fincher’s Mank.

Gary Larson has a Far Side cartoon that will stick with me for the rest of my days. In the single panel, aptly captioned “God at His computer,” a white-maned Creator sits at his desktop. On the screen, we see a piano hanging above a dopey-looking man. God’s right index finger hovers over a key labeled “SMITE,” and we can all assume what happens from there.

That cartoon dropped into my psyche at roughly the same moment I internalized the notion that every movie I’d ever seen was — first — the product of a writer doing much the same thing. I regard writers like gods. That’s part of the reason why I founded the Black List and started our annual survey of the best unproduced screenplays. Writers sit, often alone, and will entire worlds into existence.

What a joy, then, to take a virtual seat on Mount Olympus with Eric Roth, one of the greatest screenwriters of our time, to discuss his role as a producer on Mank. Directed by David Fincher and written by Fincher’s late father, Jack, Mank tells the story of how Herman Mankiewicz came to write the first draft of what would evolve into Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. It was many years before Fincher found the opportunity to make the film, but when the moment came, he turned to his trusted collaborator Roth to produce.

“David said to me, ‘I’m not asking you to rewrite anything. Let’s leave it as it is for Jack, and let’s make the best of it,’” Roth recalls. “He said, ‘I want you for two reasons: You know what it feels like to be a screenwriter, and you know the inside-Hollywood thing.’”

It’s an astute assessment, if highly abridged. Having won the Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar for Forrest Gump in 1995,Roth became the go-to writer for A-list directors like Robert Redford, Michael Mann, and Steven Spielberg, and he authored scripts including The Horse Whisperer, The Insider, Ali, Munich, and 2018’s A Star Is Born.

He first partnered with Fincher as the screenwriter on 2008’s The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, for which they both earned Academy Award nominations. That project also marked the start of a lasting friendship that is evident in their latest collaboration. With Mank, the pair worked together to deliver the soul of Jack Fincher’s script to the screen.

I spoke with Eric Roth about that experience and the craft we both revere.

Gary Oldman and Sean Persaud film a scene from Mank

Photo by Miles Crist

Franklin Leonard: When I came to Hollywood I assumed, wrongly, that screenwriters would get a lot more credit and respect than I’ve discovered they do.

Eric Roth: I think there’s been a metamorphosis. For a long time, the screenwriters themselves — and we can utilize Mankiewicz as an example — thought they were just slumming. They were making a lot of fucking money and thought they were doing just shit work. Maybe in the main they were. Great, great writers just felt screenwriting was beneath them. Then they became studio guys. In the 60s, early 70s, it became more about auteurship with Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and all those guys — and the writer became part of that shift. For a while, it felt like writers were kind of rock stars. Or is that an illusion?

Maybe it is. I think there are exceptions, certainly, but I can’t think of a period when writers got the same kind of credit that directors did. To what do you attribute that disparity?

ER: Well, the film represents a director. If it walks like a duck and talks like a duck, it’s a duck. Yeah, it wouldn’t exist without the words, but the director determines how the words are going to sound, what the thing’s going to look like, all that. I think it’s just a director’s medium in that way. It’s not like the theater, which is all language.

I don’t find writing particularly lonely. I enjoy it because I get to inhabit all these characters.

Eric Roth

There’s a director’s way, there might be my way as a writer, and then you have to find a third way or you’re never going to get out of the room. I always tell the story about Stuart Rosenberg, for whom I did some writing on The Onion Field. I loved one particular scene, and he wasn’t wild about it. We argued about it for a week, and he finally said, “Look, leave it in the script, but I’m not going to shoot it.” At the end of the day, that’s the power the director has.

With Mank, people misattribute what it’s about; they want to make it about Mank versus Orson Welles. It’s a false argument, in a way. Orson Welles did what a great director does. I’ve worked with so many great directors, and they all do the same thing: They’re spectacular at editing, rearranging, rewriting, rebuilding. It ends up being yours, as the writer, but it also becomes a hybrid.

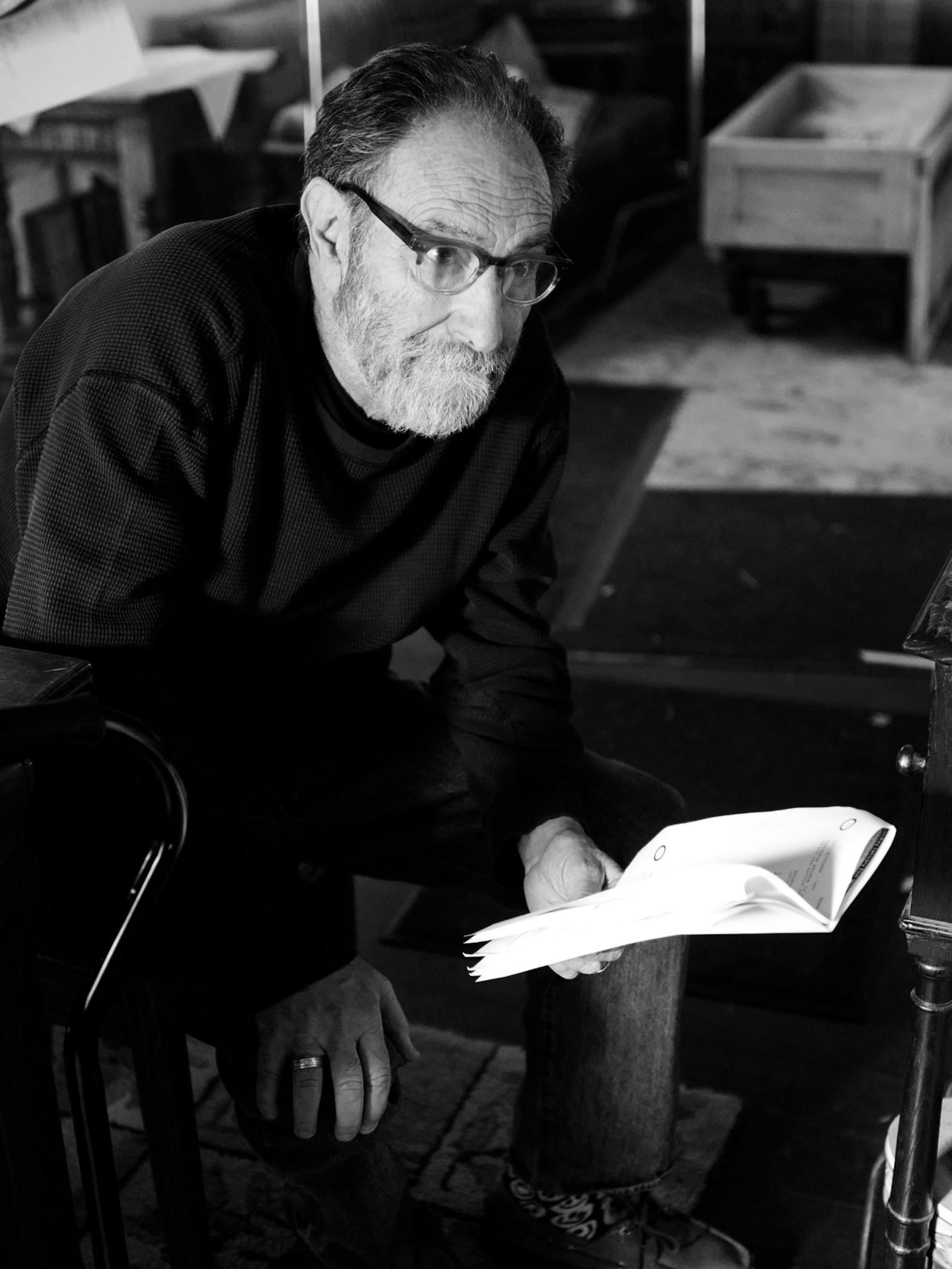

Eric Roth behind the scenes

Photo by Gisele Schmidt-Oldman

As I went through your credits preparing for this conversation, I thought there must be an Eric Roth director credit out there. There’s not, which surprised me.

ER: I never had the patience for it. I don’t have the math. I don’t have the skills to say to an actor, “Come on, man, you don’t get this?” Maybe I wasn’t courageous enough. I made one short film with this disc jockey named Sid McCoy, from Chicago. I realized that I would be a B-minus director, and why would you want to do that? Why wouldn’t you want to be an A at something? Or a B-plus, anyway.

I’m struck by this idea of Mank agreeing not to take credit on Citizen Kane and then being confronted by the fact that this may be the one thing where he decides he wants credit. Do you have something that in retrospect you feel similarly about?

ER: Well, I can tell you one that I wish I had done right away. I was asked to write One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest because I was friendly with the producer, Michael Douglas. My agent said, “They’ll never make that movie,” and I said, “Really?” That was before Jack Nicholson came on. So that’s the one I really regret. I ended up coming back and doing some rewrites. Bo Goldman, who’s as good a screenwriter as I’ve ever seen, he did it with Lawrence Hauben, and it was magnificent.

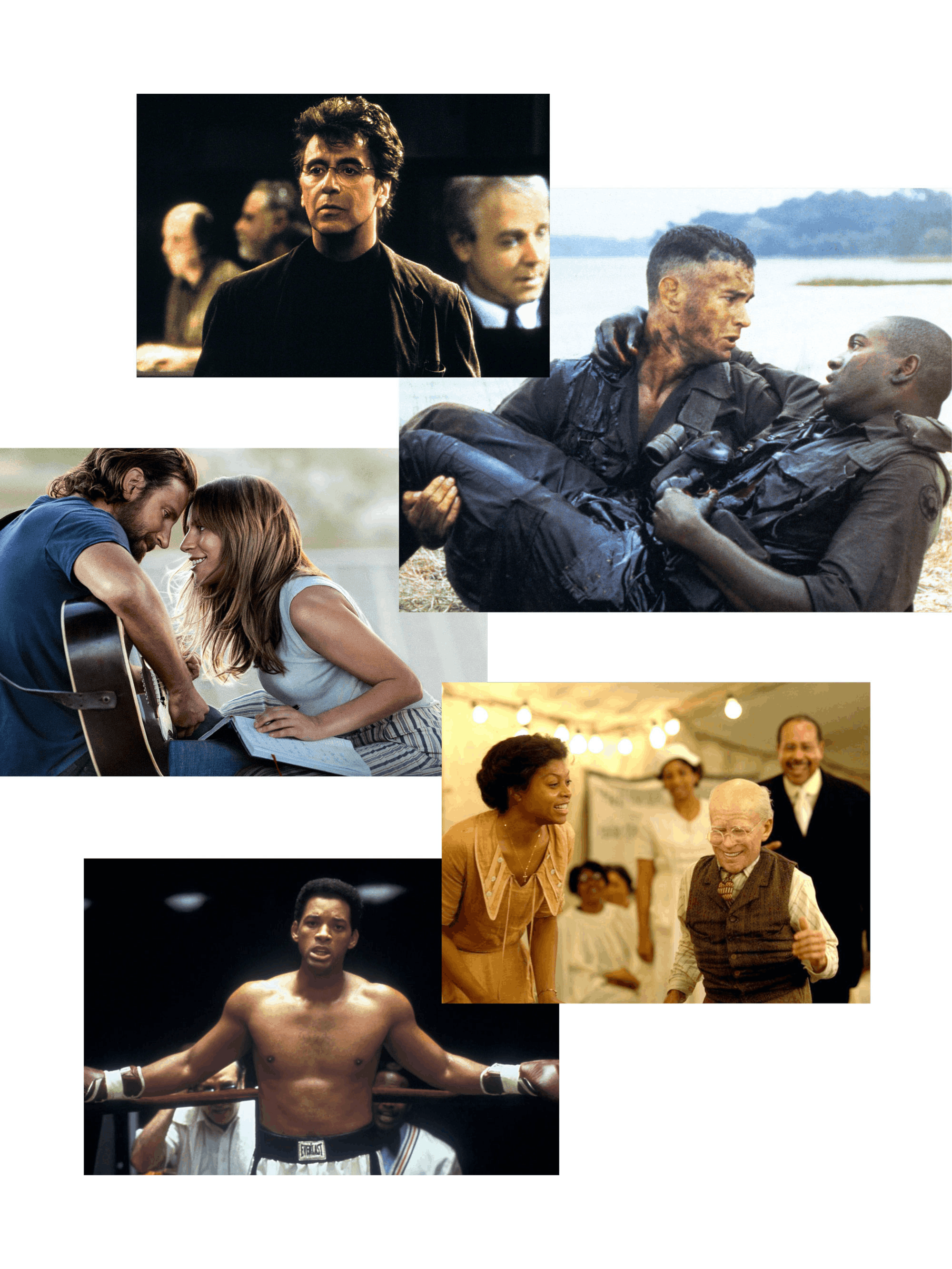

From top: The Insider (1999); Forrest Gump (1994); A Star Is Born (2018); The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008); and Ali (2001)

From Top, Images Courtesy of: Allstar Picture Library Ltd. / Alamy Stock Photo; Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo; AA Film Archive / Alamy Stock Photo; Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo; United Archives GmbH / Alamy Stock Photo

One of the other things I’ve always been fascinated by is the fundamentally solitary nature of the writer’s life. I’m curious how that resonates with you, because I’ve heard you mention in multiple interviews that loneliness is a theme that you return to a lot.

ER: Yeah, the film critic Elvis Mitchell is the one who discovered that in me. I never really thought about it, but it’s true that my work is about loneliness, people who are left alone. I don’t find writing particularly lonely. I enjoy it because I get to inhabit all these characters. I actually say the dialogue out loud — and it sounds so stupid because I can’t act, everything’s the same voice. But I don’t find it a lonely profession, because of all these worlds you get to live in. The loneliness comes in looking at the end of things, the big questions that every artist is eventually trying to measure themselves up to.

You may well be the king of the adapted screenplay. You’ve earned five adapted screenplay Oscar nominations, including the win for Forrest Gump. You have done so many indelible but less cut-and-dried adaptations of preexisting work.

ER: You’re right that not all my adaptations are obviously adaptations. The Curious Case of Benjamin Button is from a one-line idea, even though the short story was inCollier’s.I’m never going to compare myself to F. Scott Fitzgerald, but that wasn’t a great short story. Fitzgerald wrote it for money. But he had this great idea of a guy aging backwards, so I started Benjamin Button from scratch and just wrote a completely original piece. A lot of the things that I’ve written have really gone away from the text. I think it’s fair that people say, “You’ve really been great at adapting things,” but I also think I do a lot of original work.

Gary Oldman as Herman J. Mankiewicz in a scene from Mank

Photo by Erik Messerschmidt

There were various points in the last 25 years when David Fincher tried to get Mank made, but there’s a sense that this movie is more timely now, whether it’s because of this notion of speaking truth to power, or, for example, how the gubernatorial campaign of the socialist writer Upton Sinclair is woven into the plot. All these things make the film feel more urgent. Was that a subject that you and Fincher discussed?

ER: A thousand percent, yes. We could see that some of these things had to be accentuated. I remember even talking about how Bernie Sanders could have been the presidential nominee — and then you’re really in talks about socialism. We tried to educate the audience about socialism versus communism and all this stuff that we felt would be relevant. Beyond that, we accentuated the fact that this newsreel footage [that was produced in opposition to the Sinclair campaign] was not real and was not news. I think 90 percent of the newsreel content that we used in the film was exactly what was on the real newsreels.

On Mank, you’re really acting as a creative producer, bringing out the best in the existing script.

ER: I mean, I think I earned my keep. David and I are very close — he’s a marvelous treasure. We started months in advance, working at five in the morning. We’d go through the script — Is this scene in the right place? How can we enhance this one line of dialogue? — but there was never any giant rewriting that went on. I think I’ve always tried to choose things that I would be proud of at the end of the day. My legacy means as much to me as anything.

David Fincher looks on as Lily Collins and Gary Oldman rehearse on the set of Mank.

Photo by Miles Crist