It’s not an overstatement to say that there are some that may take Eddie Murphy for granted. When he burst on the scene at the age of 19 in the notorious 1980 season of Saturday Night Live, he rapidly ascended to key featured player, and by the time he exited, he had become one of the most popular cast members of the show’s history. His film career took off just as explosively with back-to-back successes in 48 Hrs and Trading Places followed by the Beverly Hills Cop franchise, Coming to America, multiple Dr. Dolittles, Nutty Professors, Shreks, and a brilliant idiosyncratic turn in Bowfinger, not to mention an Oscar-nominated performance in Dreamgirls. And then there are his two iconic stand-up films, Delirious and Raw. In the 80s and 90s, he was known as Mr. Box Office. Beverly Hills Cop (1984) is one of the top five most successful R-rated comedies in history, and Murphy’s films have grossed nearly seven billion dollars worldwide. It’s been 40 years of entertaining, and in doing so, breaking fresh ground for comedians and for African-American actors by transcending whatever prejudices or expectations culture and the industry held. In his upcoming film, Dolemite Is My Name, Murphy shines a light on a lesser-known, but equally groundbreaking performer, Rudy Ray Moore.

For this interview, I drove up to the top of Beverly Hills to where Eddie and his family live: a beautifully appointed home with impeccable grounds, yet it feels comfortable and lived-in — especially since you can hear the sounds of young children playing and see evidence of his family everywhere. Eddie Murphy may be one of the greatest comedians of all time but he is also a very serious family man. Sitting in his private screening room located downstairs — which also boasts a two-lane bowling alley, a bar with a lounge, and a state-of-the-art gym — we discussed this passion project, and how the years-in-the-making process reinvigorated his desire to get off the couch and be funny again. Also, the moment that inspired him to return to stand-up for an upcoming tour (that’s right, Eddie Murphy is going back on tour after a 33-year hiatus), as well as his unsentimental feelings for the past and his long-awaited return to Studio 8H, a place he hasn’t looked back on since his departure 35 years ago.

An edited version of the conversation follows.

Eddie Murphy

Krista Smith: Tell me about getting this story to the screen and why you wanted everyone to know about Rudy Ray Moore and his iconic “Dolemite” alter ego.

Eddie Murphy: Fifteen, sixteen years ago, I went to go see Rudy at a place in Studio City. I was like, “I think your life would make a great movie.” He was like, “Man, we should go on tour together.” And I was like, “Oh no, no [laughs].” I said, “I haven’t done stand-up in” — back then it was 10, 15 years. I said, “I don’t have an act,” and he said, “You don’t need no act, man, we just go out there and do our thing.”

So he was he still performing at the time?

EM: Yeah, he was still performing. . . . But just to have a meeting about a movie, he wanted somebody to give him a million dollars. That’s why it never came together back then. But time went on, and I was like, [if we could] get the guys that wrote Ed Wood, Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski — you know, ’cause I love that movie — if we could get them it would be perfect, because it’s a story about how he made these movies . . . [and how Rudy’s] a guerilla filmmaker. He financed the movies himself.

He was a true entrepreneur.

EM: Absolutely. . . . He cast his movies and got a distributor and all that, he did all that stuff himself. Way back in the 70s, when the big Black-exploitation wave was going on, he was the underground. Those guys were turning their noses up to Rudy’s stuff. So he had to do it the hard way. . . . It’s an inspirational story, about the most important ingredient in being creative — believing in yourself. And it’s his story. He’s not Richard Pryor, he’s not the most brilliant one. He just believes in himself. He’s the loser who would not lose. He refused to lose.

He turned so many “nos” into “yeses.”

EM: Yeah, and in the African American community at the time, the older people, you know, 40 and up, they kinda grow up with those Dolemite poems — “Signifying Monkey”; “way down in the jungle deep” — those were things you grew up hearing around the neighborhood . . . and Black folks have always loved to rhyme. Like, the first person I heard rhyming was Ali — I think all this stuff started with him. Muhammad Ali was the first person I heard rhyming about how bad and how cool he was. And Dolemite was doing that too, but he sang — it’s just as audacious as Ali saying “I’m the greatest of all time” and “I’m this” and “I’m that” . . . and the hip-hoppers say all that kinda stuff as well. I think the root of it all is Ali.

Did you have his comedy records in your house?

EM: Yeah, I had all the comedy records — Redd Foxx and Lenny Bruce and Richard Pryor and Bill Cosby. And, you know, Lord Buckley. Derek and Clive, ’cause I started doing stand-up when I was 15. So I had an interest in all of this, I used to listen to everybody. I was aware and listening to Rudy Ray Moore.

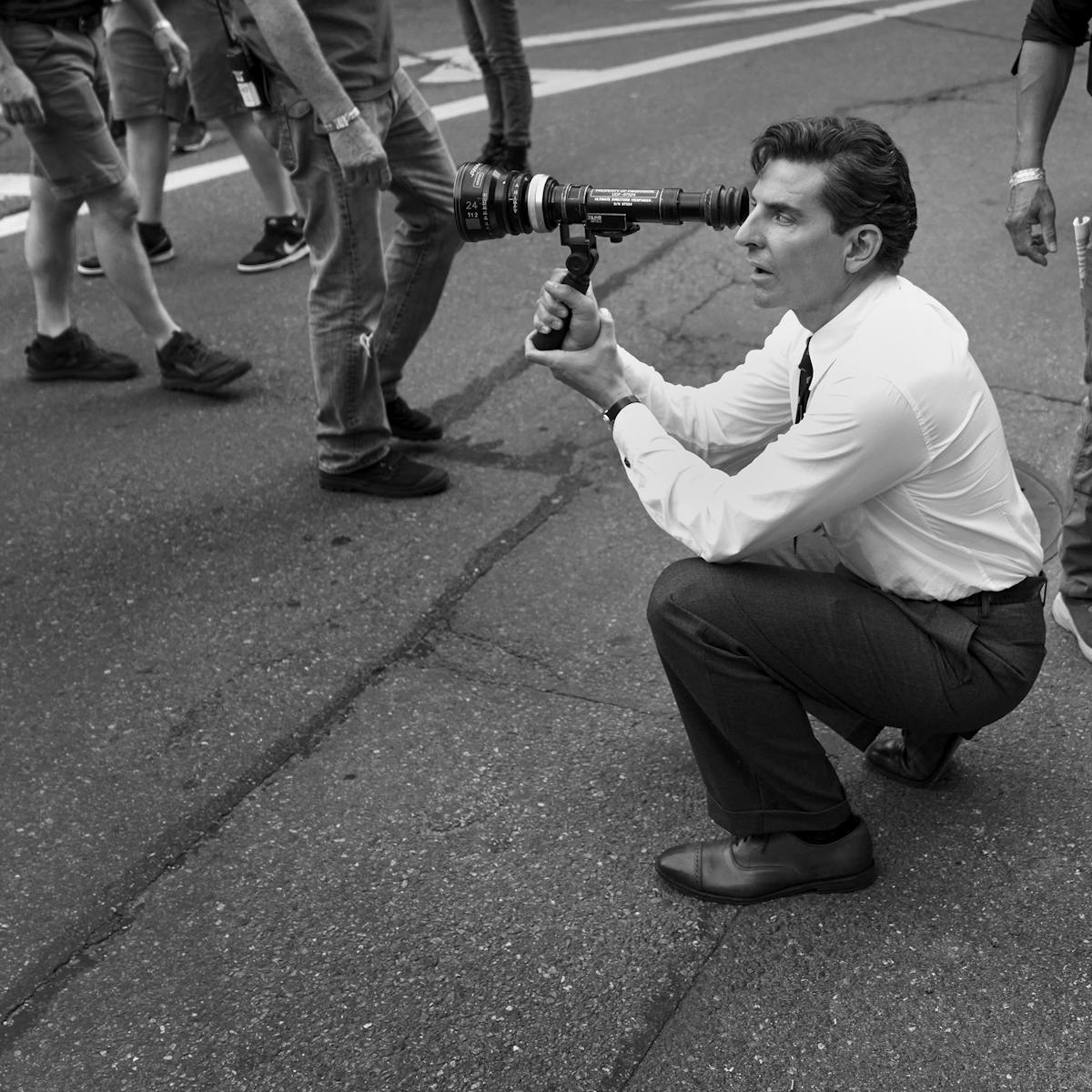

Eddie Murphy photographed for Saturday Night Live

Photo by: NBC/NBCU Photo Bank

Where’d your fearlessness come from at 15, to be able to say, “I’m gonna go do this.” I mean, now you have kids that age.

EM: I look back on it now and I was working bars. I was 15, 16, and I didn’t look at it as being fearless, I just wanted to get up there and be funny. Once I heard Richard Pryor, I was like, “O.K., that’s who I am,” because I was always the funny kid — never the class clown. ’Cause I was always kinda cool. So I was like, the cool guy in the back that would say some shit, you know [laughs]. Perfect timing, and I can do impressions of everybody. But from really early on, I was the funny kid. And that was ’75, ’76. So when I started getting on stage, I didn’t look at it as being a brave thing, I just wanted to get up there and be funny like Richard Pryor.

Youth and energy just kept propelling it forward.

EM: Yeah, that’s why there’s no fear. You know, when you’re young, you’re just going, you take everything for granted. One of the reasons why I got on S.N.L. [was] that the original cast had left and they brought in a bunch of new people. And the critics hated it. But they said the one bright light on the show was that kid Eddie Murphy. And the reason for that was because I wasn’t caught up in how grim it was . . . I was just so happy to be on TV, and I was just so happy to be funny. And that came across.

What has you happy and moving forward now?

EM: This movie — I’ve been sitting on the couch the last couple years, not doing anything, because I was like, I wanna do something when I’m excited about doing it. And this movie, Dolemite, was something I was trying to put together years ago. So when it came together, and the script that Scott and Larry put together, that we developed — I was just so excited to go to set every day. You can see it in the movie.

How long did it take to get the script right?

EM: The whole thing started, like I said, 15 years ago. The idea never went away. John Davis, the producer, came back about two or three years ago, and was like, “Hey, you still wanna do that Rudy Ray Moore thing?” [Davis also produced Norbit, Daddy Day Care, and the Dr. Dolittle franchise.]

Scott and Larry came together and they were still into it. They had just finished doing the O.J. thing that won all the Emmys (The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story), so they was red hot. And Craig Brewer (Hustle & Flow, Black Snake Moan) is the perfect guy to direct it — everybody that’s involved with the movie, we were all Rudy Ray Moore fans. We were [already] part of the cult of people that liked his movies.

Eddie Murphy

You’ve assembled an all-star crew here. You have Chris Rock and Snoop and Mike Epps, and Wesley Snipes. But you also have an enormous discovery in Da’Vine Joy Randolph as Lady Reed.

EM: She’s a great find.

She’s impressive. She graduated from Yale and was nominated for a Tony, right?

EM: Yeah, I know she was doing stuff, but I think this one’s really gonna let people see who she is. She’s really good in the movie. Really, really good.

The costumes by Oscar winner Ruth Carter (Black Panther) are incredible. What was your favorite part about going back into 70s L.A.?

EM: I never felt like I was going back — I’m not like that, up in my head. I know I’m on a movie set. I could tell you the most unpleasant part about doing the 70s is the outfits, how uncomfortable those clothes are. That’s the stuff we were wearing when I was a teenager; I don’t remember it being that uncomfortable. You wear some platform shoes now, in your 50s . . . and you’re like, fuck — that’s a young person’s shoe. I just turned 58 — I was 57 when I made the movie. You put on a platform shoe, and you will hear your foot saying, “Fuck this shoe!” [Laughs.]

It looked like you guys had a good time making it as well, and that comes across. The chemistry and the music. This is the first time you’ve ever played a real-life character on film, correct?

EM: Yeah, this is the first time I ever played an actual person, and I didn’t have to look up anything because I was a genuine fan. I have all his records, all his movies — and I’ve watched ’em for years and years. When this came together, I didn’t have to study his voice. I already did an impression of him. It all just fell together.

I think your age brings a vulnerability to it too, which makes the performance so good.

EM: What you mean, being an old fucker — that brings the vulnerability to it? [Laughs.] It absolutely does.

Why do you think Rudy’s movies struck such a chord?

EM: First and foremost, they work because they’re funny, and also the crudeness of it — to see a microphone in the frame, to see he missed a punch. Those are the things that made the movies appealing — the rawness of it.

His movies became like stoner movies. They didn’t start out like that, they started out as just . . . people couldn’t believe what they were seeing. And then when hip-hoppers started watching ’em, they became stoner movies. Like, for me anyway, a Fellini movie or Alejandro Jodorowsky movie or Putney Swope by Robert Downey Sr. It became one of those types of movies.

What do you hope an audience takes away from a movie like this?

EM: I think it’s a really inspirational story about believing in yourself and going for your dreams. What’s really cool about it, though, is usually when a person’s going for their dream, you know, they have incredible talent. But not Rudy . . . Rudy’s movies are horrible. His stand-up was horrible. But his spirit, and the fact that he believes in it so much — he makes it not horrible.

If you looked at it on paper you would be like, What the fuck? But because of how much he believes in it — he sells it to you. We’re making a movie about him and it’s 40 years after he did those movies. So it’s a great story, about how if you believe in yourself, that’s the most important ingredient. You don’t have to be a genius. You don’t have to be incredible. You just have to believe it, no matter what it is. That’s a great universal story.

Are you happy you got off the couch to do it?

EM: Yeah, yeah. I’m happy I got off the couch. And I’m getting ready to go do Coming 2 America. . . . I haven’t been back to Saturday Night Live in 35 years, so I think I’m gonna go host S.N.L. this year. And then next year, I’m gonna tour, do some stand-up. Then back to the couch.

I watched your 2015 Mark Twain Prize acceptance speech, and it felt like a stand-up set. When you heard that laughing and how everyone were responding, how did that feel when you walked offstage?

EM: That night I was like, “O.K., I could still do that.” It had been awhile since I had talked like that and got laughs. That’s when I started thinking, maybe I should do some stand-up again. But I don’t wanna just pop-up, come off the couch, be out there doing stand-up. It was like, I wanna have a movie, you know, something that was really, really funny. And the way this came together was like, I can show up out there. ’Cause this movie is, you know, it’s inspirational and it’s all of those things. But more than anything, it’s really, really funny.

Is there anybody you want to do on S.N.L., impersonation-wise, that you’ve been thinking about?

EM: No, I don’t have anyone that I’m dying to do. Look, when I’m on the couch, I’m like, really on the couch. I don’t think about, like, “I’m dying to do an impersonation.” [Laughs.]

You’re on the couch.

EM: Yeah, I’m really, really on the couch.

Eddie Murphy

All right, I want to talk about your life off the couch — your legacy. Chris Rock has spoken publicly about how you’ve been such an inspiration, that if you hadn’t been Eddie Murphy on S.N.L. he’d just be a funny U.P.S. driver in Queens.

EM: Is that what he said?

He’s also said that you were the first Black actor that he saw who actually played things like a person, instead of a caricature.

EM: That’s what Chris said? That’s very nice of him.

Do you ever think about your career in terms like that? In movies like Trading Places and 48 Hours? What made you so incredible in those parts is that you turned the tables, you were in control — in a basically all-white world.

EM: Yeah, but you don’t set out to be those things. Providence made those things happen. It was kinda like, it’s the movie business. They see it a certain way and every couple of years, something will happen and they’ll go, “Oh, you can make movies like that?” With African Americans it was — with the exception of the Black-exploitation era — it was like one at a time, one Black person at a time was getting on-screen, and it was always grown-ups. And it was always a certain type of character that you were playing — a sidekick or the buddy or something.

Then I show up, and I’m cast as a buddy and the sidekick in 48 Hours, but I’m kinda like the catalyst. I’m the buddy, but if you listen to what’s happening in the movie, it’s like, “What’s our next move, convict?”; “Now tell me what we gotta do.” So, I was kinda the first African American actor to be in movies where I go into the white world and take charge. And be funny.

How did you learn to deal with that pressure of being Mr. Box Office and forging the path for different kinds of movies?

EM: I never felt like I was forging a path. I was just being who I was, reacting to whatever blew my way. I just adapted to it. . . . So when I was in the middle of it, I didn’t feel like I was opening any door or I was being groundbreaking or anything. It’s when you look back, years afterward, and you’re able to take in what you’ve done.

What was your inspiration for playing multiple characters in a movie? What you did with The Nutty Professor — with you as every person at the family table is unprecedented.

EM: I had ideas ’cause there were movies like that, that I had seen. I love Peter Sellers, and he did great characters. Like in Dr. Strangelove, he played multiple characters in that. There was a movie with Alec Guinness called Kind Hearts and Coronets, and Richard Pryor did a movie called Which Way Is Up, where he played multiple characters.

You know, when I was about 9 or 10, I asked my mother to get me a ventriloquist dummy for Christmas. And the very first thing I ever tried to do was be a ventriloquist. Even from the very beginning, I’m trying to be more than one person. I’ve always gravitated toward that, the multiple character and the makeup stuff. I liked the Planet of the Apes and Hunchback of Notre Dame.

The reason I’ve done so much of it is because it frees you up. It’s like, everybody has their little moves, actors have their little moves that they do. The audiences get used to seeing you do it a certain way. And when you put the makeup on, you can’t do your moves. You have to be, they’ll say, “You can’t do those, you’re this old lady.” Or “you’re this old Jewish guy.”

Or you’re this obese professor, so you have to come up with different ways of being funny. It was fun for me as an actor. Like this Rudy Ray Moore thing was, O.K., now you’re playing a comedian. So you got your moves that you do, you can’t do your Eddie Murphy funny moves, you can’t do the funny laugh. . . . You have to be funny like Rudy Ray Moore. And that was the challenge as an actor.

Rudy Ray Moore and Eddie Murphy

What was that like in rehearsals and when you’re shooting? Like, what’s the difference between Rudy Ray’s “fuck” and Dolemite’s “motherfucker?”

EM: I don’t know that they’re different [laughs]. What do you mean they’re different? The motherfuckers are different?

Well, just for a second, let’s talk about the word “fuck,” O.K., because from my perspective, Eddie Murphy taught me to swear.

EM: Did I really?

Mm-hmm.

EM: Oh, I’m sorry.

No, I love — are you kidding? You used bad language as an art form.

EM: Did I?

Mm-hmm. And what I was saying was, the way you say “fuck” as Rudy versus how you say it as Dolemite, that was a choice you made as an actor.

EM: Well Rudy, I got to see who he was, what he was really like in life, as a person. And Dolemite was this character, you know, who I was a big fan of for years. Nobody’s that character you see up there on the screen at the movie theater. Or when I’m doing comedy, you know, that’s a character or a comic persona — as opposed to doing music, which is kinda like, that’s me.

How important is music to you? I mean, you’ve been putting out records for decades, right? “Party All the Time” came out in 1985.

EM: I’ve never stopped doing music. I stopped putting it out, though, ’cause, you know . . . it weirds audiences out sometimes, and I wasn’t doing it to get more famous, or to have a hit record or something. I just do it ’cause I love to play. My chops have gotten better. I always have a studio wherever my house is, so I record a lot. That’s what I do the most. When I’m on the couch, you know, I’m on the couch with a guitar. And what I do mostly in my spare time is music. Writing and recording.

It just lives in its own Eddie Murphy library?

EM: Yeah, I’ve got all types of songs and collaborations with people. [Laughs.] All different types of stuff from over the years. Never released. I’ve been in a studio with everybody over the years. Everybody.

And you never release it?

EM: All that stuff will come out, one day . . . a hundred years from now when I’m gone, they’ll find all these tracks and be like, “Wow, we didn’t even know this guy.” [Laughs.] “We had no idea.”

That’s why it stays private?

EM: Yeah, it’s intimate. You express yourself and put a record together. You know, it’s something personal. You put it out and, “two thumbs down” — you be like, What the fuck? [Laughs.] What do you mean, “two thumbs down?” So I don’t even serve it up for that stuff. . Being funny is enough. Now, when I tour next year, the audience will have to sit through, you know, two or three songs before I start telling jokes.

Bobby Rush, Eddie Murphy, Eddie Levert, Walter Williams, Jimmy Lynch, Eric Grant, and Mike Epps attend the LA Premiere Of Netflix’s Dolemite Is My Name

Photo by Frazer Harrison/Getty Images

How do you find the whole political-correctness climate for stand-ups? Does that give you any pause?

EM: No, because back when I was doing stand-up, the words “political correctness” hadn’t come up yet. But I had people picketing and talking shit back then, so it was always like that. I know you gotta choose, pick your shots now, stuff that you say.

Do you get nervous at all about the idea of going back on tour?

EM: When I think about doing stand-up . . . it’s like if you go to the pool and ask if the water is cold, and someone says it’s freezing. And then before you jump in, you go, “Ooh, it’s gonna be freezing when I first get in.” That’s how I feel with stand-up. Not nervous or scared, I just know that the water’s cold.

And you’ll get used to it.

EM: Yeah, you get used to it.

So, you dedicate Dolemite to your brother, and I know family has always been so important to you. What do you want people to know about Charlie Murphy?

EM: He’s the first person that told me about Rudy Ray Moore. He was a comedian, and this is the first thing I’ve done in so long that was funny. And you know, I love my brother. I miss him. That’s why I dedicated it to him, and put his name on it — something I know is gonna make people laugh. He made so many people laugh when he was here.

Do you think you have another generation of actors coming up in your family?

EM: Yeah, my daughter Bella, she’s gonna play one of the princesses in Coming 2 America. And my oldest daughter, Bria, she’s an actress. And then my sons Miles, Christian, and Eric all write and act. So yeah, eventually you’ll be seeing them.

Do they make you laugh?

EM: Oh yeah, the kids are nonstop. Hilarity. [Laughs.]

Do you miss New Jersey at all? Or New York?

EM: Yeah, you know . . . I don’t really have that. That’s not the personality trait for me.

Are you sentimental?

EM: I can be sentimental but I don’t pine for the past. Or things in the past, where I used to live… If I was missing it id have it around. I have a small circle of friends that, you know, we’ve been friends for 40 years.

Do you look forward to things?Are you looking forward to going on S.N.L.?

EM: Look, I don’t like to do anything as much as I like to sit on the couch.

Do you get dressed every morning to sit on the couch? Is there a routine for sitting on the couch?

EM: No, I don’t have a routine. For me, the best time is when there’s nothing scheduled and there’s nothing to do. . . . My kids are around, or everybody’s around. That’s the best for me. That’s what I look forward to. And the other stuff is work. You sit on the couch, you get rejuvenated. That’s another thing about resting. If you get some rest, when it’s time to do what you do, you do it better.

Are you rested?

EM: Oh yeah, my batteries are charged. This Rudy Ray Moore movie kinda lit a spark under me. ’Cause you know, you’re sitting there with an audience, and you see them laughing, and it’s like, “Yeah, yeah, oh yeah, that’s what I do.” I got them laughing. I wanna do something else while I got ’em laughing.

Eddie Murphy