The cast and co-showrunners give an oral history of the seminal Dear White People in celebration of the final season.

When the history books chronicle Justin Simien’s Dear White People, they’ll describe the series — and the 2014 feature film — as bold and audacious. They’ll hail the show for its willingness to talk about subjects from white supremacy to sexual assault, colorism to a woman’s right to choose, in ways that were both full-throated and unvarnished. Dear White People helped change the landscape of television, serving as a model for the storytelling made possible by young Black people, and other historically excluded folks.

But back in the early 2000s, when Simien was a film student at Chapman University, he simply wanted to translate his experience of navigating the predominantly white institution as one of its less prevalent Black faces. “The premise of it sounds so vague — an ensemble of people of color speaking articulately about their experiences — but I just remember thinking it would work,” Simien recalls. “It was so hard to convince people of that.”

While working in marketing and publicity after graduating film school, Simien turned to social media to test out his vision. Enlisting some of his actor friends, he created digital content and a concept trailer for Dear White People, which he described as a satirical film about being a Black face in a white place. The social campaign went viral, helping him raise more than $40,000. The campaign also caught the eye of prolific producers Stephanie Allain, and Effie T. Brown, and TV writer Lena Waithe. Together, they helped the comedy-drama cross the finish line.

A rejoinder to “post-racial” sentiment often espoused by white people who saw the election of President Barack Obama as proof that racism had ended, the film made a splash upon its Sundance Film Festival debut in 2014. Starring Tessa Thompson, Tyler James Williams, Teyonah Parris, and Brandon Bell, Dear White People won the festival’s U.S. Dramatic Special Jury Award for Breakthrough Talent. Three years later, Simien adapted its premise for television, premiering a new incarnation on Netflix to both acclaim and controversy.

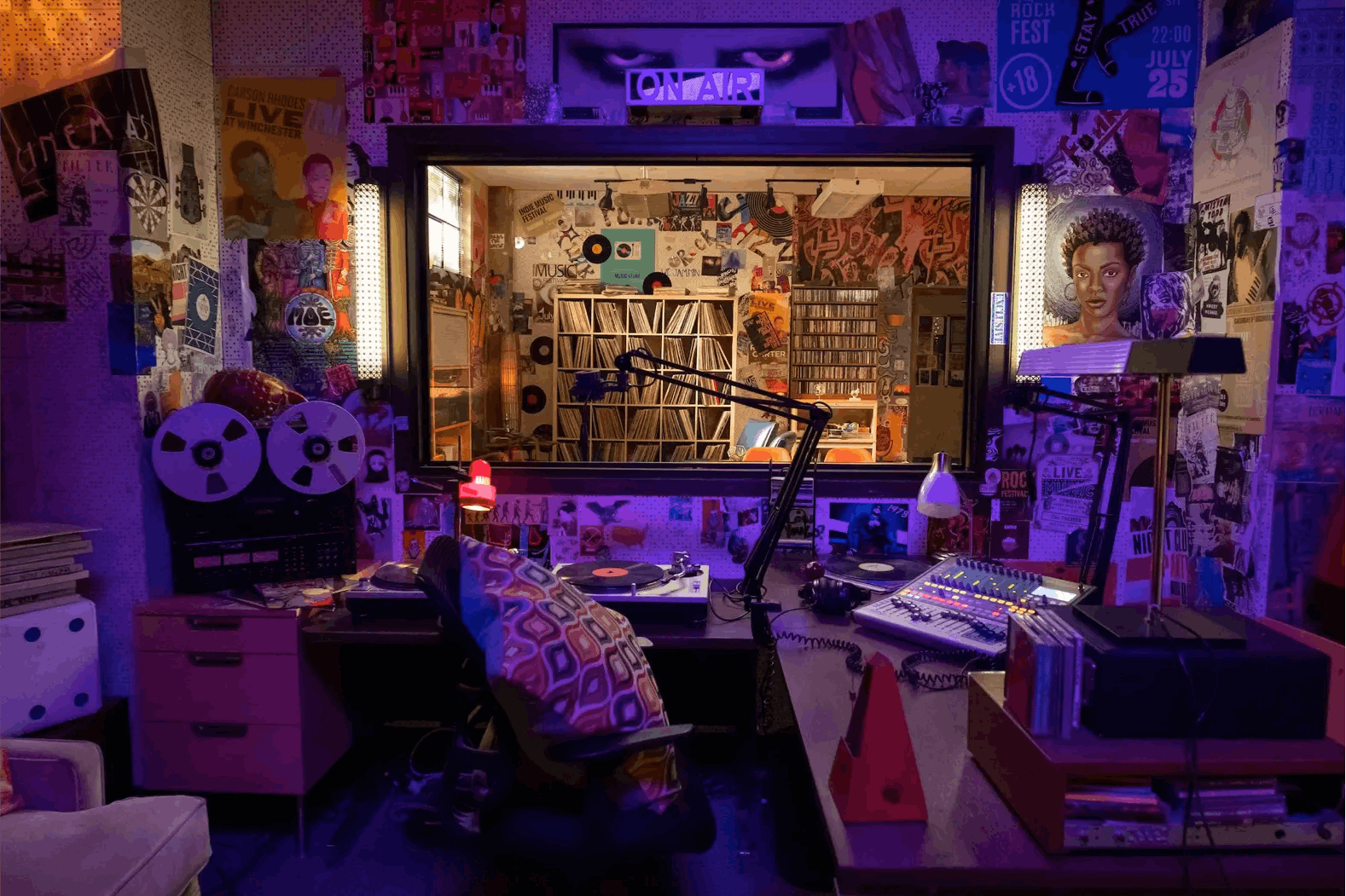

Offering an alternate take on the events depicted in the film, the series spotlights the experiences of Black students at the predominantly white Winchester University leading up to and in the aftermath of a campus blackface party. Logan Browning plays Sam White, host of the college radio show that gives the series its title. She’s joined by DeRon Horton’s gay student journalist Lionel Higgins; Antoinette Robertson’s bougie, status-hungry Colandrea “Coco” Conners; and John Patrick Amedori’s well-meaning white dude (and Sam’s boyfriend) Gabe. Reprising their roles from the film are Marque Richardson as the tech-minded activist Reggie Green, Ashley Blaine Featherson as future doctor Joelle Brooks, and Brandon Bell as son-of-the-dean Troy Fairbanks.

Since its 2017 premiere, Dear White People has taken hold in the cultural zeitgeist, exploring the enduring effects of police brutality and the rise of the alt-right, as well as the dangerous spread of misinformation and the ways the #MeToo Movement has increased accountability for predators. The series’ three seasons have served as reflections of our lived experiences as seen through the eyes of Black millennials.“

The first season and the movie are really growing out of, ‘Hey guys, racism is full-on still a thing. Thank you for Obama, but we’re not done yet,’” Simien says. “Every single piece of the show after the first season is us processing the reality of America and it showing its whole ass to us unabashedly.”

In advance of the show’s fourth and final season, which premieres Sept. 22, I spoke with the cast and co-showrunners Simien and Jaclyn Moore about Dear White People’s impact, their favorite storylines and on-set memories, and what it was like to create a show that frankly addressed race long before the social reckoning of 2020.

Dear White People was a passion project for Simien, one he called on his friends to help him perfect. While the road to the film’s release in theaters — from table reads to raising money and getting investors; filming in 21 days in Minneapolis to the Sundance premiere; and beyond — wasn’t without hiccups or controversy, everyone involved believed in Simien’s vision and knew this was a movie the world needed to see.

Marque Richardson (Reggie Green, film and series): I remember doing a table read for Dear White People, just as a friend helping another friend hear it out loud. And then I remember stalking Justin like, “Yo, I have to be in this movie.” I auditioned for Troy and Lionel and didn’t get those parts. After one of the auditions, I left feeling like I just bombed. I sent him an email apologizing. He emailed me back and said, “Never apologize for your work.”

Brandon Bell (Troy Fairbanks, film and series): Dear White People was my first feature film and it meant so much, not just because it was first, but also because of the subject matter, the characters, the world. I was fortunate enough to be part of Justin’s table read and trailer that he used for the Indiegogo, so I was very aware of the amazing possibilities of sharing this narrative, that had not really been seen in this way before, through his brilliant outlook on life. When the film finally came to fruition, it was a joy. It felt like the beginnings of something really cool and maybe even a shift toward new players in this storytelling world.

Ashley Blaine Featherson (Joelle Brooks, film and series): There was a lot of anticipation about the film. Dear White People was my first feature, so I was so excited with my four or five lines. I remember people being really intrigued by it, but also some backlash and confusion, and people saying it was racist. Justin was a great captain of the ship because he believed in it and knew that it was going to change the modern landscape of film, and [later] television.

Antoinette Robertson (Colandrea “Coco” Conners, series): Dear White People became a catalyst for bigger conversations that we had privately as people of color but never publicly. I thought it was brilliant.

Justin Simien (creator, writer, director): When we showed the movie at Sundance — not our opening night, but in the town with real people coming to see it — I was terrified. I was like, “Oh my God, they’re not an industry crowd. They’re not L.A. people. Are they going to get it?” I’ll never forget this woman — she was a librarian, maybe in her mid-fifties — coming up to me and telling me that she’s a Coco. I remember being blown away at that moment, realizing I had accomplished the thing white people do all the time. Because when I grew up, I had to see myself in white people and white characters, and it was second nature, seeing myself in people who don’t necessarily look or talk or act or live like me. To think that I brought this character to the screen that really hadn’t been there before, and it made a human connection with someone I didn’t know, that was a powerful moment. I think that’s when it clicked in me what we do this for.

Logan Browning (Sam White, series): When Dear White People came out, I was like, “What is this? Why are we writing letters to white people?” I was so confused, like “I don’t think it’s for me.” Then my friend invited me to a screening, and I loved it.

Jaclyn Moore (co-showrunner): I went to see Dear White People at the Regal Cinemas in Union Square. I remember being so blown away in the theater to the point that I tweeted, “If somebody was smart, they would give the Dear White People people a lot of money to make this a show.”

Sam White (Logan Browning) and Joelle Brooks (Ashley Blaine Featherson)

One of Simien’s regrets about the movie was that it did not directly address activism or police violence “in any meaningful way,” he says. After winning the Sundance award, he made a deal with Netflix to spin the film into a series, knowing he wanted to include that element. To do so, he originally planned to kill off one of the main characters. Although he changed his mind after some advice from former showrunner Yvette Lee Bowser, Season 1 of Dear White People set the stage for a show as timely as it was entertaining.

Simien: When I left Sundance, I truly did not know how March was going to get paid for. Rent money was a major factor — just keeping it real! But also, creatively, it was my first movie. We made it for $1 million, and I didn’t get to do nearly 70% of what I wanted to do. I was just so excited that I was going to get to tell more stories, particularly about Lionel. The fact that this gay, quiet, nerdy, Black boy character could be out here with multiple adventures and anxieties and all kinds of storylines that I lived but never saw anywhere, that was really exciting to me.

Bell: My initial thought was, “Really?” just because there hasn’t been a good track record of adapting film to TV. But I knew Justin was involved, so that put a lot of those worries to rest. Then I wanted to know if the entire cast was returning — Tessa, Tyler, and Teyonah were all on other shows. I was a little nervous how Justin would make it work in terms of persuading people that these beloved characters could be played by anyone other than the original actors.

Simien: The original concept was to have all of the film’s cast members come back and do the series as a continuation of the film. That became a total impossibility because of how long it took to get things off the ground and a few of them already being on shows on other networks. Only two or three of the film’s cast were able to return.

Browning: Because I saw the film, I got the email from my agent and responded: “Hey guys, I think you sent me an old audition because I saw this movie.” They told me it was being turned into a show. I remembered seeing myself in Sam, when I finally saw the film; I immediately said, “This is me. I’m about to play this role.”

We were just telling the truth, and as the truth aligned with time, it created this very interesting dichotomy of art and life.

Logan Browning

John Patrick Amedori (Gabe, series): I didn’t watch the film before I did the show. I knew that I was doing a character that someone else had previously played, and as a performer, I didn’t want to be influenced by whatever they did. I watched the trailer and some other scenes that didn’t have Gabe in them, so I could at least get the vibe as much as I could. Then I followed my own instincts.

DeRon Horton (Lionel, series): I think I was in college when I first heard about the movie and the title really threw me. I don’t even think I watched it when it first came out, but then I had an audition for it. I watched it and thought it was brilliant. So that made me want to audition for the series more.

Robertson: I was so excited to hear that they were extending the film into a show. Coco had resonated with me on so many levels as a dark-skinned woman, and I was excited for the opportunity to portray her in my own way.

Moore: We knew Season 1 was going to be built around two things from the beginning. We knew we were going to retell the story about the blackface party from the movie, and then we knew that there was going to be an incident of police violence that was going to happen at some point in the middle of the season. Originally, Lionel was supposed to die, but by the time we got to the writer’s room, that idea had been backed away from.

Simien: I thought it’d be powerful to take a character that was really the heart and soul, frankly, of the piece, the kind of Black guy that you just wouldn’t “expect” things like this to happen to, and show the brutal truth of it. Yvette Lee Bowser was like, “You can’t kill yourself off the show. Lionel is your conduit into the show, and if you kill yourself off, you won’t have that anymore.” She was so right. I think about it all the time, because so often the instinct of artists is to tell tragic stories about ourselves, especially if we’ve been through some shit. But for Black folks, it’s different because that is how our life is, and sometimes we need something to help us imagine what it can be. We need to see ourselves live and make mistakes and be messy and still survive. I’m so glad I didn’t do that.

Moore: Justin has this great magic trick that he pulls with his writing, which is that he takes a very complicated issue, and rather than trying to solve it, which is what most TV shows do, he spreads out the conversation based on what the characters we’ve created actually feel and believe. He takes all of these different opinions and then leaves them in a real-life place where nobody’s right but nobody’s wrong, or somebody’s right about some things, but wrong about something else. It’s very much not an after-school special, but I feel like a bad version of our show would be.

Sam White (Logan Browning) and Gabe Mitchell (John Patrick Amedori)

The first part of Season 1 retells the story of the blackface party from the film. Then, in Episode 5, directed by the Oscar-winning Moonlight filmmaker Barry Jenkins, Reggie (played by Marque Richardson) is held at gunpoint by a campus police officer. (The experience of filming this installment remains particularly memorable for the cast and crew; the episode represents the series at its best.) Also of note: The last day of shooting for the season was Tuesday, Nov. 8, 2016 the night Donald Trump won the presidency. “John Patrick and I were filming the very last scene on the last day, and I remember I was like, ‘John Patrick, we can’t let everyone’s rain cloud affect our work — we just have to be in our own little bubble and protect each other,’” Browning says. “I feel like that’s the thing I’m going to take away, that we were always concerned about protecting each other.”

Moore: When we were making Season 1 of the show, there was a segment of Hollywood who were like, “Is this necessary?” because the show was written as a sort of take-down of the fantasy of a post-racial America. Then, when Trump won, we suddenly felt like Chicken Little. We had been yelling that the sky was falling, and everybody had been like, “Those dramatic Dear White People kids.”

Bell: In retrospect, I think we all were too lax about Trump, but I’ll never forget being on my phone that night like, “Y’all, I think he’s winning.” There was a scary feeling in terms of where the country could move. But one of the great things about Justin as a creative, as a writer, is he always has his ear to the streets. Everything, in every season, has been ahead of its time, because we typically shoot the show six months before it airs. When it comes out, it’s still right on time with the cultural conversation.

Simien: The most important thing I said to the writers is: Whatever is going on in terms of the social justice aspect of the show, whatever issues are on the characters’ minds, that was never to be an A storyline. Because the show isn’t about race. I mean, it is, but at its core, it’s about who you are versus the role you have to play in society. I love the Toni Morrison quote, “The very serious function of racism is distraction.” Though we talk about all of the distractions that get in the way of these characters figuring out who they really are, I wanted to clue everyone in to what the core of the show was, because if we didn’t care about the characters and their inner journeys, and their journeys weren’t something we could relate to, the social justice stuff would sound like noise or it would get preachy.

Browning: We had no idea how much the world would need this show while we filmed it. We made a piece of work in a pre-Trump era that was released in a post-Trump world. We were just telling the truth, and as the truth aligned with time, it created this very interesting dichotomy of art and life.

Moore: There was a huge backlash when the first trailer came out for Season 1 that was pretty traumatic in a whole bunch of ways. Because I had been a semi-public figure on the Internet writing about politics, I got death threats. I think Justin had death threats, too.

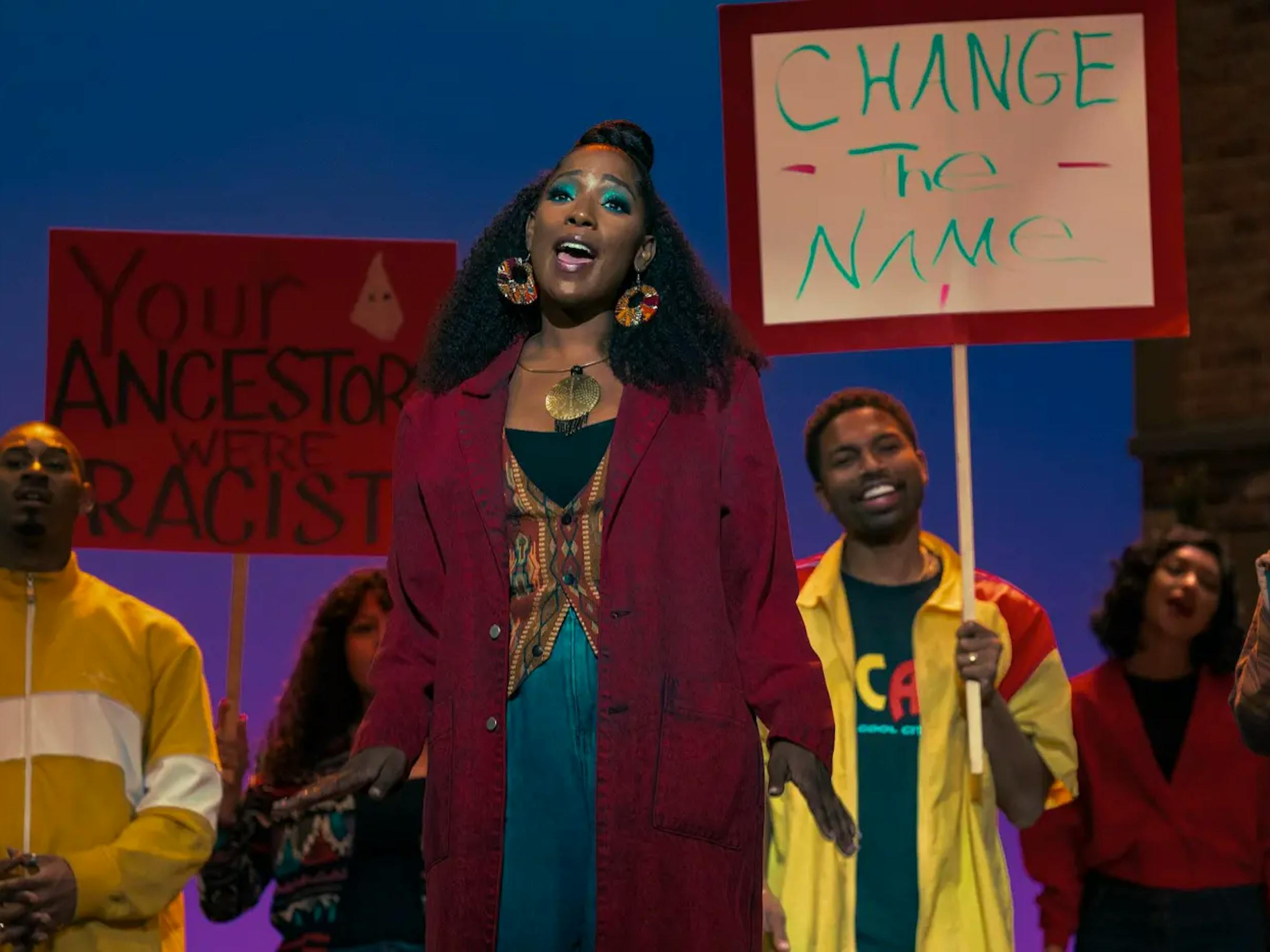

Browning: One of the most precious monologues to me is Sam’s at the end of Episode 1. She’s talking about blackface but also the actions that lead to blackface. It’s one of the few times we say real names of Black victims of police brutality. I said Trayvon Martin, Sandra Bland, Philando Castile. When I spoke their names, I had their photos in front of me. In that moment, the show crossed the barrier from fiction to reality, and I feel like that is what will always stay with me. We were not just playing pretend on television.

It was a transcendent and cathartic experience for us; people were crying. People were physically upset and production held space for us. It bonded us as a cast.

Ashley Blaine Featherson

Simien: Reggie became the way in which we talk about the issue of police violence. In what I think is probably one of our best episodes in Season 1, he gets a gun pulled on him. How that lives on in his body afterwards has become such an important part of the show.

Richardson: It was a moment for all of us, the gun being drawn on Reggie, and then him sitting on the floor behind his door, broken. It wasn’t written like that, but the story broke me internally.

Bell: Obviously, we’ve been dealing with police violence forever, and we’re still dealing with it today. The energy on set was just traumatic. Tears were flowing left and right; it was awkward. It was uncomfortable because of the truth we were trying to present, but everybody came together and supported each other. I remember the weight of that on Marque’s shoulders and us just being there to support him. You felt it in your bones if you were on set, whether you were crew or cast — background, principal, writer, director — everybody felt it.

Amedori: The day that we shot that scene, we took it very seriously. We were very precious with Marque’s performance, the crew, and the cast. There was a moment where it got very real, and we had to take a 10-minute siesta, huddle, and regroup. It was a pivotal milestone in the production.

Featherson: It was a transcendent and cathartic experience for us; people were crying. People were physically upset and production held space for us. It bonded us as a cast.

Richardson: That episode actually shifted the rest of the season. Episode 6 was supposed to get back to the rest of the story and move on, but we couldn’t just move on from that moment to everything being okay. For myself, that shifted who I wanted to be as an artist and what art could be for me. It shifted what I wanted to do in the world and the kind of work that I want to continue to put out. Dear White People is kind of a foundation for myself in the projects that I choose moving forward. It’s really set me up on a foundation of being intentional with my heart and what I choose to do.

Reggie Green (Marque Richardson)

Season 2 focused on “how American history is all about erasing what actually happened to marginalized people,” Simien says. The writer-director also chose to highlight the rise of misinformation online as a direct response to a troll campaign against the series, which accused the show of harboring racist attitudes toward white people. In Season 3, a #MeToo storyline dealt with the concept of fallen heroes. Blair Underwood was cast as Reggie’s mentor Moses Brown, who is accused of sexual impropriety.

Bell: The one thing that I was involved in, and had no clue about the impact it would make, was the scene with Lionel coming out to Troy in their shared bathroom. I’ve been involved in theater my whole life, so the gay community was nothing new or scary to me. I played it how I would have responded. After it aired, I remember the response: “I thought that was so cool, how Troy’s gay roommate came out to him and it wasn’t a thing. It was like an instant acceptance.” Obviously, the L.G.B.T.Q.+ community hasn’t had the easiest time, specifically within the Black community. So, to get that response was awesome and a testament to Justin’s writing.

Robertson: Of all the topics the show brought up, I deal with colorism the most on a day-to-day basis. I get discriminated against based on having a darker complexion so much so that the disappointment that stems from it is now second nature. I’ve learned to deal with it, but the sting never becomes less devastating.

Browning: Where I grew up and how I grew up, it was just all Black all the time, but I never really took a step back from my identity of Blackness and thought about how I’ve benefited from colorism. It blew my mind, and it wasn’t just the show — It was listening to Ashley and Antoinette in their interviews too. It’s one thing to act it, but when I hear the people I know talk about their real-life experiences, I’m like, “Oh wow, Logan. There’s something else for you to wake up to here.”

Robertson: I also loved Season 2, Episode 4 where Coco falls in love with the idea of loving and being loved unconditionally by her unborn child Penelope in the way she’s always wished. It opened up a bigger conversation about women’s health that we’ve needed to have for a very long time.

Moore: One of the toughest things we’ve done on the show was the Moses Brown story in Season 3. We wanted to explore problematic heroes and the idea of having to reckon with the legacy of somebody who has done a lot of good for you, but done a lot of harm for others. That was something all of the writers felt, to varying degrees, personally affected by.

Troy Fairbanks (Brandon Bell) and Lionel Higgins (DeRon Horton)

For the fourth and final season of Dear White People, Simien wanted to explore the idea that the “American dream” shouldn’t be our metric of success. “All you have to do is grow old enough to realize that none of those things make you super happy, and even something like social justice seems to always get bogged down in capitalism and publicity and ego and all these things. Figuring out what it’s all for is why I made the season.”

Bell: Season 4 is wild, and I hope people will love it; given the last few years we’ve all experienced, that’s an important aspect. Joelle says it in Season 2: “Sometimes being carefree and Black is an act of revolution.”

Browning: I am so grateful to have been a part of Dear White People because I think it is so ahead of its time. Summer 2020 has shown us that the show was ahead of its time by at least a couple of years, but I think that in a decade, or in two decades, people are going to look back and go, “Wait a minute. They were talking about this then. Why hasn’t the world changed?”

Robertson: Coco taught me so much. She showed young Black women we could be ambitious, assertive, articulate, sexual, boss-ass beings and that those things are not mutually exclusive. I watched her struggle through finding her place in this world as I, Antoinette, also struggled to find my place in this world. Through her vulnerability I found my own strength. I’m forever changed by portraying such a complex, beautifully misunderstood being. Colandrea will always have my heart.

Horton: I get D.M.s sometimes from people who say, “You really helped me show my family who I am because I never had somebody to identify with on TV.” Justin would always talk about saving people. When it’s on that scale, people talking about the show saving their lives and being able to show themselves to their families, then yeah I feel like I did my job.

Robertson: Dear White People spoke about race relations before it was fashionable to do so, boldly encouraging youth activism and speaking truth to power. We were never incentivized by accolades, nor was the show diluted to be made palatable. I’m proud of the work we did and I’m excited that new generations can experience it for the first time.

Simien: I’m proud that there are Lionels everywhere now. My pride really goes to him because queer people have the shit end of the stick. Black people have the shit end of the stick. You combine the two and it’s a hot mess. What I like about this moment is that Lionel doesn’t have to be every gay Black man, but he’s like some gay Black men who otherwise wouldn’t have seen themselves. That really fucking matters so much more than reviews or viewership numbers. That’s a legacy thing. Even when I’m in my feelings or something doesn’t go the way I want it to go, just knowing that I’ve been able to at least do that keeps me going.

Joelle Brooks (Ashley Blaine Featherson)