Director David Fincher looks back on how Mank made it to the screen.

When Jack Fincher became a parent, he shared his lifelong love of cinema, and his regard for screenwriters in particular, with his son, David. “Jack felt this was a really difficult kind of writing, and something he had great respect for,” David Fincher says, looking back. “He also believed that the beleaguered writer was not a cliché due to personality type, but because they often had to bite their tongues as they watched idiots take their ideas and mangle them.” (On that point, the Oscar-nominated director begs to differ.)

Eventually, David encouraged Jack — who was by that time retired from his journalism career — to try his own hand at screenwriting. Those efforts have now solidified into one of David Fincher’s most acclaimed films to date, a project that also serves as an homage to his father, who died from pancreatic cancer in 2003.

Mank chronicles how screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz came to pen the first draft of what would one day be Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. Like so many films, Mank was years in the making, and it long loomed in David’s consciousness. Father and son initially discussed the idea in the 1990s, when David was graduating from music-video director to rising-star filmmaker. As Jack completed various revisions, they had many fruitful clashes over the direction of the screenplay.

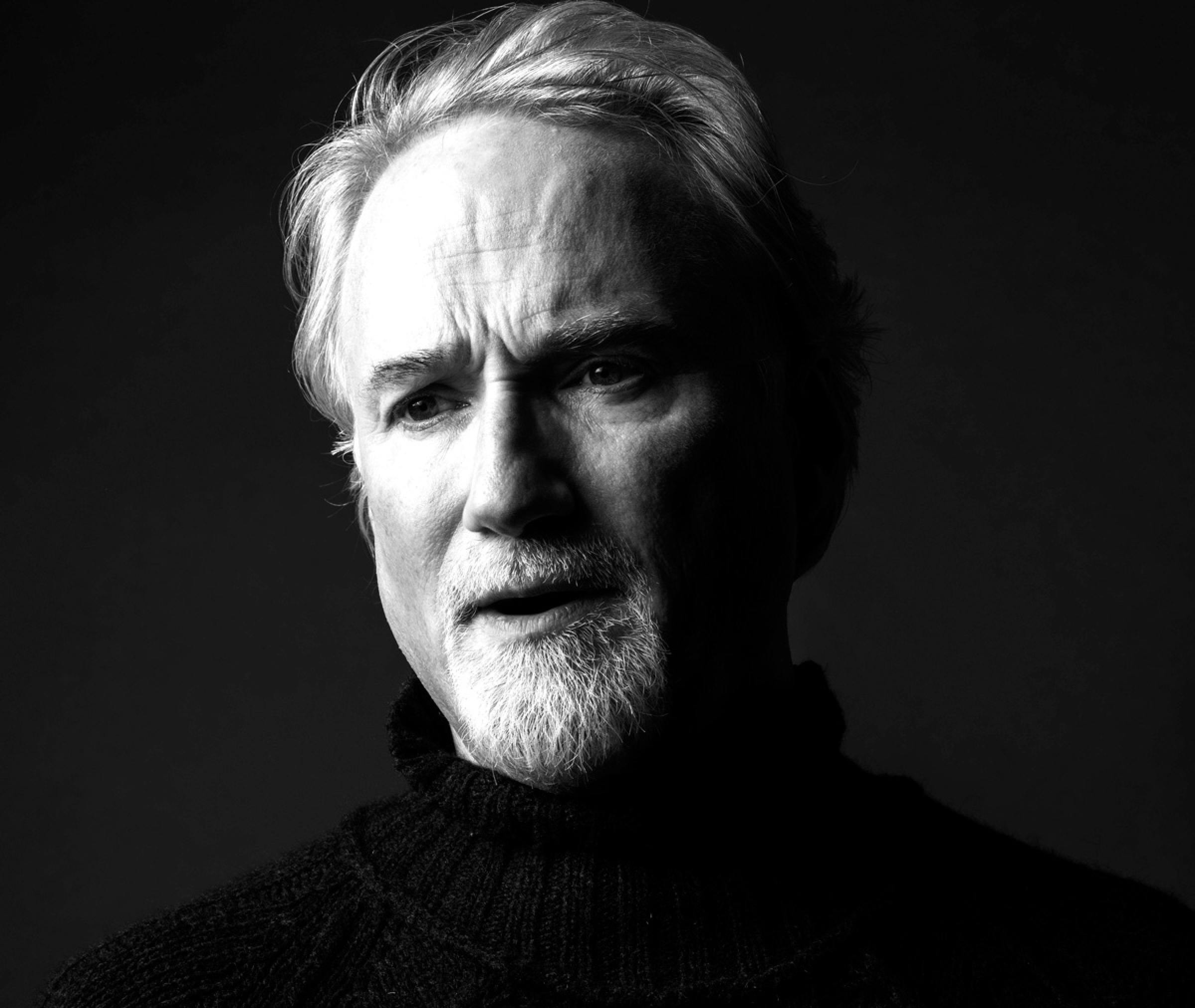

Gary Oldman and David Fincher on set

Photo by Miles Crist

Over the years, it became clear that the project was unlikely to see the light of day. It fell by the wayside and Jack fell ill. “He ended up having chemo to worry about, and not so much the rewrites,” David recalls. “We would talk about it from time to time. I would take him to his chemo — he was in therapy a little bit in the last couple of months of his life — and we would talk about it in the car, shoot the shit. But it was understood that this would not be something that would ever get made. And that was O.K.”

David Fincher moved forward, building an acclaimed body of work that includes Zodiac, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, The Social Network, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, and Gone Girl. Ultimately he arrived at a place where he could turn his focus to that elusive project from his past. Suddenly, Mank was something that could get made, and made the way he wanted: in dazzling black and white, with a superior cast carrying it forward.

The only thing that we did was take every scene and go, Let’s blow the pixie dust off this.

David Fincher

Nev Pierce spoke to David Fincher in this edited excerpt from the book Mank: The Unmaking.

Nev Pierce: Let’s go back to the beginning. When did you first see Citizen Kane?

David Fincher: I didn’t have the opportunity to see it until middle school. I’d heard so much about it from my dad. I inherited from him this notion that Citizen Kane was the greatest American film ever made. I remember telling my dad, “Hey, we’re gonna watch Citizen Kane in film class today.” He was giddy. He was a big Welles aficionado. At the time, he thought the makeup was great and the performance was transformative. But the thing he kept coming back to was how cinematic it was. There was no talk of Mankiewicz. I remember dreading seeing it, because I didn’t want to be let down. And I was amazed by it. I remember being completely swept away by the speed at which it got its points across and the confidence of the directing. I was aware that I was seeing something that had a force. And it was a thing we got to share.

When did the idea for Mank come about?

DF: I know Jack had read Pauline Kael’s essay “Raising Kane.” He had a copy in his personal library. In the late 80s, I was visiting my parents and found it and read it — and we talked about it then. When Jack retired in the early 90s, he came to me and said, “I’ve got this time now, and I want to write a screenplay. What should I write about?” I said, “Why don’t you write a screenplay about Herman Mankiewicz and Orson Welles?” I tossed this out glibly, saying, “This could be something you might be interested in, and I would certainly be interested in reading a screenplay about it.”

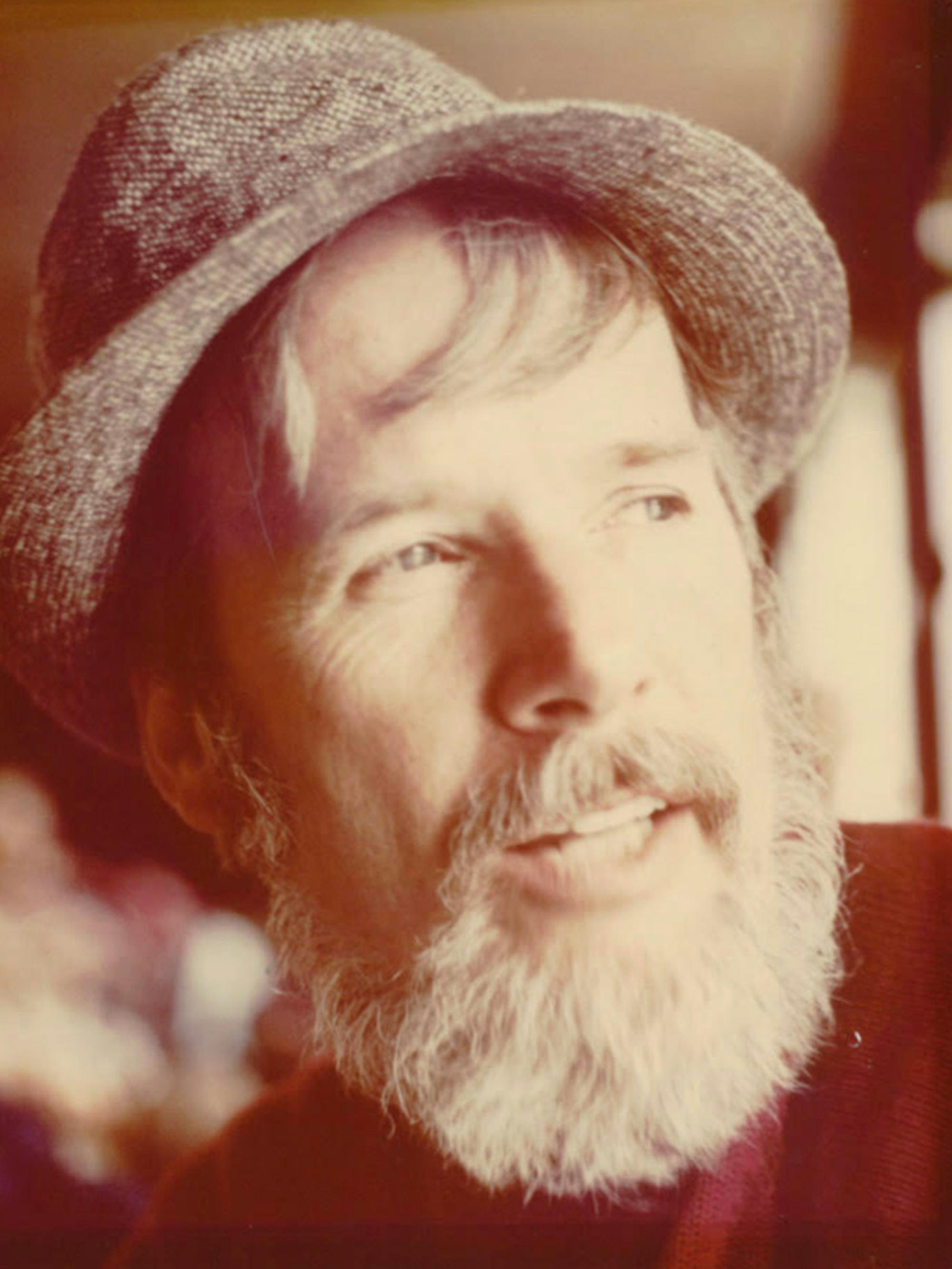

Jack Fincher

Photo by Jane Goodwin

Jack had some very specific ideas about writers and their sometimes diminished value, but that wasn’t really of interest to me. I just hoped to put a bug in his ear, and he went and he wrote a script. It was very much a saber-rattling: Directors are pompous fuckwits who take advantage of... ! I remember thinking that this didn’t ring true to my experience.

When you went back and forth with Jack on the script, how frank were you?

DF: I remember coming home when I was seven and saying, “A California Highway Patrol car is following our school bus,” and he said, “Yeah, well there’s this guy named Zodiac, and he’s a serial killer, and he has vowed to shoot out...” It never occurred to him to sugarcoat anything. It was a source of peculiar pride, his honesty. He just cut to the chase. There were definitely times as he was writing this draft where I was pretty honest, saying, “I think this scene is shit. I don’t see why it exists in this story.” He would get loud: “Because it does all this heavy lifting!” Eventually, he would come around. But everything in the final draft is in service of his impetus.

The thing that was not in his first draft was a key component of Mankiewicz’s self-loathing: He thought he was slumming in Hollywood, working on things a notch above nickelodeons, you know? He was in his era’s version of the music-video business. It was only when the handcuffs were off and he didn’t have to answer to the Louis B. Mayers or the Irving Thalbergs — and he was working with somebody who was interested in a sharp stick in the eye — that he was challenged and that he found a degree of self-respect.

David Fincher behind the scenes with Gary Oldman and Lily Collins

Photo by Nikolai Loveikis

Why was Gary Oldman the right choice to play Mank?

DF: Gary has a primordial decency, and you can’t fake that. He’s a complicated guy, but that was perfect for Mank. Mank was a complicated guy. He was really, really funny, and he was really, really sad, and he was really, really angry, and he was really, really compassionate — he was a great shoulder to cry on. So the role needs somebody who’s going to take all that on. An actor playing this part is going to have to juggle four or five plates at the same time.

And, really, when you’re making a movie about a generational wit, it’s probably good to have a generational actor. There’s no reason to have somebody in a role like this who doesn’t inspire some kind of awe. We had to get a kind of a lovable thing with Mank. He had to be somebody where you’re hanging on his every word to hear what tightrope he’s going to stretch for himself next. There has to be this amazing gregariousness that makes him not only the keeper of the gin but the life of the party.

What about Charles Dance as William Randolph Hearst?

DF: At one point I talked to Mike Nichols about playing Hearst. I don’t think he could see himself acting in that role. I started thinking about people that I had worked with that I loved and thought could be playful with the text. Hearst is a tricky role because you cast somebody basically for the last scene. When Charles came aboard, we knew that he was going to ostensibly be an extra until he gets his chance to speak. We needed somebody who could embrace that, be a good sport about it. Charles was incredibly generous to me on Alien 3, incredibly supportive of what it was I was trying to do. He’s so regal and has such a great presence and bearing that I thought if we could talk him into taking the 10 weeks of the extra role in order to be able to do two days of the reason we cast him, we’d be really well off.

David Fincher and Gary Oldman

Photo by Gisele Schmidt-Oldman

He truly has a mysterious quality about him.

DF: There was an element of reclaiming the real people from Kane. I feel like Charles Foster Kane is Mank and Welles’s creation. A lot of the things that happen through Kane and to Kane are things that happened to Hearst, but I think there are more monstrous elements to Hearst. Hearst liked having Mankiewicz around. I don’t think that he ever saw himself as somebody who needed to protect his legacy from Herman. I think there is a tiny sense of betrayal in that Mank had been allowed into the inner sanctum and had overheard a lot of interactions between these people and knew a lot about them. I wanted to talk about the Truman Capote aspect of, Well, if you didn’t want to read about it, why would you have that conversation in front of me?

When you’re working with a writer, or in this case your producer Eric Roth, are you sitting for a few hours each day talking things through scene by scene, line by line, going, “Not sure about this”?

DF: The process was more sitting with him and saying, “I think this is what [was intended],” because I’m pretty savvy to what Jack Fincher was about. But none of the scenes changed. Literally every scene is the scene that was written. The only thing that we did was take every scene and go, Let’s blow the pixie dust off this. When Jack was talking about filmmaking, he was talking about something he had read about. When Eric and I talk about filmmaking, we’re talking about something that we do 14 hours a day, five and six days a week. It’s a slightly more informed and less reverent view.

It is always seduction and negotiation and belligerence.

David Fincher

The script is the blueprint, but it’s not simply a question of executing what’s on the page.

DF: I think the analogy of architecture is a really good one. There is the intention, right? And then there are the geological realities of the site, and all of the shortfalls that make you adapt or change the blueprint. There are all those things that go into finishing something that started off as blue lines on white paper and now is something that people are going to live in and hopefully invest in. I feel like architecture is a pretty good analogy for filmmaking because, yeah, the script is imperative, the blueprint is imperative, but you’ve got to have the flexibility to say, Wherever we thought we were putting the basement, that’s now moved. That’s just the reality of best-laid plans.

What’s your view — or what do you think Jack’s view was — on the notion of the director as auteur?

DF: When your son is a director, you have a fairly realistic view of what auteurism is: It’s a misnomer. Anybody who knows anything knows trying to get the troops to all face the same direction is fucking hard. I don’t believe in auteurism because I don’t ultimately feel that anyone can inform a moment so explicitly that what everyone is in service to is simply that one person’s idea.

It’s ultimately going to be a process that involves a lot of people and a lot of dirt and a lot of waste-making. We always say, “Movies are not finished; they’re abandoned.” You’re going to go, “It’s the best I can make it, given all of the things...” It is always seduction and negotiation and belligerence. That’s what makes it so amazing, and so depressing. It’s just fucking hard. It just takes a lot of energy. I’m 58. I cannot imagine doing this at 77. I mean, Clint Eastwood is 90 fucking years old. I have literally no idea how that’s possible. I look at it this way: If you really want a challenge, if you never want to be happy with what you’re capable of, by all means, direct. I say that joking, but laughing, crying and desperately serious.