How director Paolo Sorrentino and cinematographer Daria D’Antonio captured the majesty of Naples in their newest collaboration.

Paolo Sorrentino’s The Hand of God is his most personal film to date, an intimate portrait of Fabietto Schisa, a young man coming of age in Naples in the 80s, told in elegant simplicity. “The only filter is the reminiscing, the memories, and feelings I had as a boy,” says Sorrentino. “I was not concerned with a specific idea of style in this film. I felt it had to come out quite naturally.” Using the acclaimed writer-director’s own childhood and family tragedy as a prism, The Hand of God is quieter than Sorrentino’s earlier works, allowing its characters, including the city of Naples, to sing.

Seeking a naturalistic approach to the film, Sorrentino enlisted fellow Naples-born cinematographer Daria D’Antonio, the first woman to win the Globo D’Oro for Best Cinematography twice, for her work on Ricordi? and La pelle dell’orso. Queue brought Sorrentino and D’Antonio together to hear more about their experience filming the divinely photographed The Hand of God.

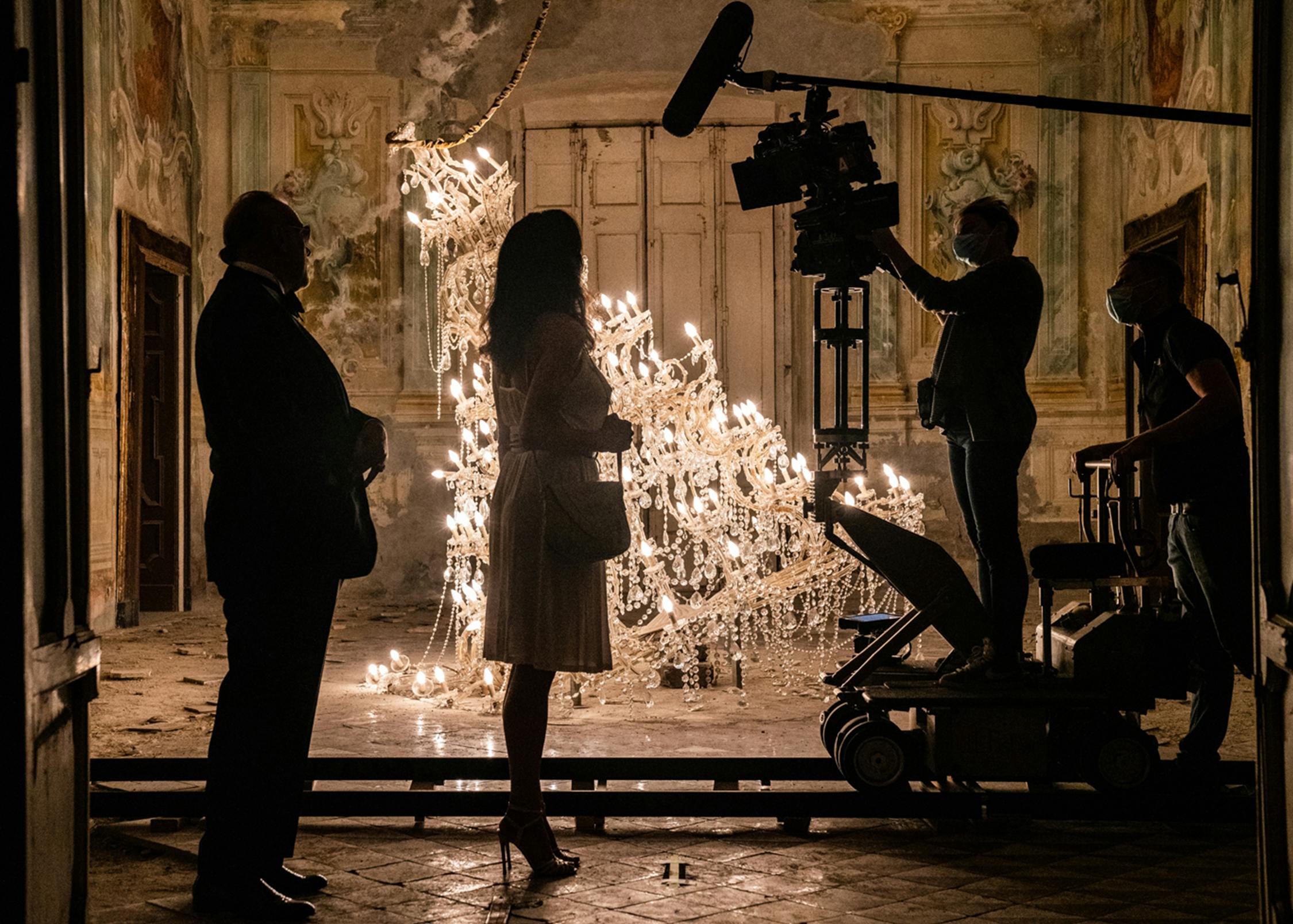

Paolo Sorrentino, Daria D’Antonio, and The Hand of God crew

Queue: How did you two start working together?

Paolo Sorrentino: If I remember correctly, we actually met on the set of Capuano’s film, Polvere di Napoli. That’s the director who’s portrayed at the end of The Hand of God. It was a film I wrote with Capuano in 1997 or 1998, so that’s almost 24 years ago. It was the first screenplay I had written.

Daria D’Antonio: I was doing video control and was an assistant camerawoman.

PS: And then we started working together when?

DD: On your first short film!

PS: Ah yes, L’amore non ha confini, my first short film that should be forgotten. We made some more short films, some commercials, and then we decided to make this first feature film together.

DD: You decided.

PS: Yeah, okay, I decided!

Fabietto Schisa (Filippo Scotti)

Daria, what were you feeling after reading the script for The Hand of God the first time?

DD: Being that it’s a very heartfelt film, I was happy that he asked me to make it. There was a kind of “performance anxiety” of making our first feature film together, but above all I was worried about being able to feel the story he wanted to tell, which was so intimate. So, I felt very happy, very excited, but also very worried about disappointing him.

Paolo, what made Daria the best choice as director of photography for this film?

PS: First of all, it was in the air that sooner or later we’d make a feature film together. I mean, it’s one of those things that is a bit implicit, that you don’t say to each other, but you feel is getting closer. She’s so talented: Film after film, she’s increasingly better and more flexible. It’s not the case that we can only work together if we make films about Naples, but the fact that it’s set in Naples was an extra something. We’re both from Naples, we share a very common city area, our families are more or less of the same social background. There’s an age difference unfortunately, because I am older, but we’ve got very similar backgrounds. I think we also have a propensity for melancholy and some similar weaknesses. So, I think we had all the prerequisites to agree on what this film should be. And, in fact, we understood each other by saying very little because we saw it in the same way. Daria was very good at achieving exactly the photography I wanted without me being able to tell her. She did it of her own initiative.

Which scene was the most difficult to photograph?

DD: Maybe the lunch sequence because it was shot over many days, with many cameras. I was more anxious about that one, but then he told me something that I’ll always remember. He said “Don’t get caught up in this thing, the connections, the light. This isn’t just one lunch — these are all the lunches of our adolescence.” This really opened up a world to me because it was true, and because he definitely had thought about it and would edit it that way. So I was more serene. That was definitely the one thing that worried me the most because it was spread over so many days, and it was a scene with a lot of acting and so many actors.

What was important to grasp about Naples for each of you?

DD: For me, it was important to be able to express the many nuances of Naples because it’s a complex city. It’s a city made up of many things, and it’s full of memories and life. So, it was important for us to have something different from what we’re used to seeing and also a little less superficial. It’s how Paolo fit the characters in the city, which is a strong character itself — some things can only happen in a place like Naples. In part, we are the product of that atmosphere, that history; our families are a certain way because we grew up there. It’s a place with a thousand faces and it was important to try to render all of them, even if it wasn’t a conscious thought. It was important to try to give back all the emotions that the city gave us. We grew up like this because we grew up here. I don’t know how to explain it, perhaps you can explain it better.

PS: I can’t explain it any better. What Daria says is right. It’s very difficult for us to say something about Naples because we are so imbued with it, as it’s the first place we knew and therefore a place that represents everything we are and have become. So, it can be difficult to focus on. Paradoxically, cities are better understood and examined minutely by those who come from the outside because they see things from a certain distance. We don’t have that distance, as we’re inside. It’s no coincidence that the film is full of scenes of the sea; I understood why I put so many of them in, even though I am neither a great swimmer nor one of those people who are really obsessed with the sea. But the sea gives you a great idea of freedom, a useless freedom: in front of you there’s the sea, but then you can’t go anywhere because you can’t just swim forever.

And that’s exactly the idea I had as a boy, that I was free — both when I had so-called family restrictions and when I no longer had my family. And in this case, too, just like the sea, I didn’t know what to do with this freedom, I didn’t know how to use it. As a matter of fact, I didn’t do anything with it. I stayed in my parents’ house for decades, with the same furniture, the same things, when I could have left instead, I could have lived freely. I only have regrets in this respect. The Berlin Wall fell and I could’ve gone to Berlin to see a momentous event, and I didn’t even think about it. I was free, but I didn’t know how to use that freedom. When freedom is total, it inhibits you, it overpowers you, and so you’re afraid of it, you can’t handle it.

The Hand of God crew

Were there any moments on set that caught you by surprise?

PS: The sea takes me by surprise, and in this film we went to sea many times. The point is that nothing stays still at sea, so it’s crazy. The sea moves, it gets rough, the boats turn — it’s all a surprise at sea. There’s the actor throwing up because the sea is rough, there’s someone jumping overboard, the support boats come into the frame. There was every reason to lose your patience, actually. If I have to think of a moment when I was caught off guard it’s at sea because it’s a moment when the set belongs to God, not me.

DD: You have less control, exactly, you can do less.

Daria, what inspires you about Paolo’s work?

DD: What a question! First of all, I’m very inspired by him because, apart from everything, I think he has a lot of courage — no matter what he says — he has a lot of courage in the stories he tells, in the way he tells them, the stories he decides to tell. I’m very inspired by the fact that he always puts himself on the line and always raises the stakes.

And Paolo, what inspires you about Daria’s work?

PS: Putting aside technical skill, what I really like is to watch her work from a character point of view. That is, I really like the fact that she’s firm and resolute. I really like seeing and learning from her leadership skills. I think she’s very good at managing people who work with her and she does it with a perfect blend of grace and an iron fist. Often when I have time, I study her to mimic her, and then try to lead in my own way because I have rougher and more questionable manners than her.

Fabietto Schisa (Filippo Scotti) and Patrizia (Luisa Ranieri)